Malathion

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Diethyl 2-[(dimethoxyphosphorothioyl)sulfanyl]butanedioate | |

| Other names

2-(dimethoxyphosphinothioylthio) butanedioic acid diethyl ester Malathion Carbofos Maldison Mercaptothion Ortho malathion | |

| Identifiers | |

| ATC code | P03 QP53AF12 |

| 121-75-5 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:6651 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL1200468 |

| ChemSpider | 3864 |

| DrugBank | DB00772 |

| |

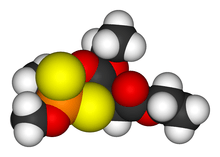

| Jmol-3D images | Image |

| KEGG | D00534 |

| PubChem | 4004 |

| |

| UNII | U5N7SU872W |

| Properties | |

| C10H19O6PS2 | |

| Molar mass | 330.358021 |

| Appearance | Clear colorless liquid |

| Density | 1.23 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 2.9 °C (37.2 °F; 276.0 K) |

| Boiling point | 156 to 157 °C (313 to 315 °F; 429 to 430 K) at 0.7 mmHg |

| 145 mg/L at 20 °C[1] | |

| Solubility | Soluble in ethanol and acetone; very soluble in ethyl ether |

| log P | 2.36 (octanol/water)[2] |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | 163 °C; 325 °F; 436 K (greater than)[3] |

| LD50 (Median lethal dose) |

290 mg/kg (rat, oral) 190 mg/kg (mouse, oral) 570 mg/kg (guinea pig, oral)[4] |

| LC50 (Median lethal concentration) |

84.6 mg/m3 (rat, 4 hr)[4] |

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |

| PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 15 mg/m3 [skin][3] |

| REL (Recommended) |

TWA 10 mg/m3 [skin][3] |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) |

250 mg/m3[3] |

| Except where noted otherwise, data is given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Malathion is an organophosphate parasympathomimetic which binds irreversibly to cholinesterase. Malathion is an insecticide of relatively low human toxicity. In the former USSR, it was known as carbophos, in New Zealand and Australia as maldison and in South Africa as mercaptothion.[5]

Pesticide use

Malathion is a pesticide that is widely used in agriculture, residential landscaping, public recreation areas, and in public health pest control programs such as mosquito eradication.[6] In the US, it is the most commonly used organophosphate insecticide.[7]

Malathion was used in the 1980s in California to combat the Mediterranean Fruit Fly. This was accomplished on a wide scale by the near weekly aerial spraying of suburban communities for a period of several months. Formations of three or four agricultural helicopters would overfly suburban portions of Alameda County, San Bernardino County, San Mateo County, Santa Clara County, San Joaquin County, Stanislaus County, and Merced County releasing a mixture of malathion and corn syrup, the corn syrup being a bait for the fruit flies. Malathion has also been used to combat the Mediterranean fruit fly in Australia.[8]

Malathion was sprayed in many cities to combat West Nile virus. In the Fall of 1999 and the Spring of 2000, Long Island and the five boroughs of New York City were sprayed with several pesticides, one of which was malathion. While it was claimed by some anti-pesticide groups that use of these pesticides caused a lobster die-off in Long Island Sound, there is no conclusive evidence yet to support this.[9]

Manitoba ordered the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba to be sprayed in July 2005 as part of the West Nile virus campaign. Prior to this, malathion was used over the last couple of decades on a regular basis during summer months to kill nuisance mosquitoes, but homeowners were allowed to exempt their properties if they chose. Today, Winnipeg is the only major city in Canada with an ongoing Malathion nuisance-adult-mosquito-control program.[10][11]

Medical use

Malathion in low doses (0.5% preparations) is used as a treatment for:

- Head lice and body lice. Malathion is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for treatment of pediculosis.[12][13] It is claimed to effectively kill both the eggs and the adult lice, but in fact has been shown in UK studies to be only 36% effective on head lice, and less so on their eggs.[14] This low efficiency was found when malathion was applied to lice found on schoolchildren in the Bristol area in the UK and it is assumed to be caused by the lice having developed resistance against malathion.

Preparations include Derbac-M, Prioderm, Quellada-M[16] and Ovide.[17]

Risks

General

Malathion itself is of low toxicity; however, absorption or ingestion into the human body readily results in its metabolism to malaoxon, which is substantially more toxic.[18] In studies of the effects of long-term exposure to oral ingestion of malaoxon in rats, malaoxon has been shown to be 61 times more toxic than malathion.[18] It is cleared from the body quickly, in three to five days.[19] According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency there is currently no reliable information on adverse health effects of chronic exposure to malathion.[20] Acute exposure to extremely high levels of malathion will cause body-wide symptoms whose intensity will be dependent on the severity of exposure. Possible symptoms include skin and eye irritation, cramps, nausea, diarrhea, excessive sweating, seizures and even death. Most symptoms tend to resolve within several weeks. Malathion present in untreated water is converted to malaoxon during the chlorination phase of water treatment, so malathion should not be used in waters that may be used as a source for drinking water, or any upstream waters.

If malathion is used in an indoor, or other poorly ventilated environment, it can seriously poison the occupants living or working in this environment. A possible concern is that malathion being used in an outdoor environment, could enter a house or other building; however, studies by the EPA have conservatively estimated that possible exposure by this route is well below the toxic dose of malathion.[18] Regardless of this fact, in jurisdictions which spray malathion for pest control, it is often recommended to keep windows closed and air conditioners turned off while spraying is taking place, in an attempt to minimize entry of malathion into the closed environment of residential homes.

In 1981, the late B. T. Collins,[21] Director of the California Conservation Corps, publicly swallowed and survived a mouthful of dilute Malathion solution. This was an attempt to demonstrate Malathion's safety following an outbreak of Mediterranean fruit flies in California. Malathion was sprayed over a 1,400 sq mi (3,600 km2) area to control the flies.[22]

In 1976, numerous malaria workers in Pakistan were poisoned by isomalathion, a contaminant that may be present in some preparations of malathion.[23] It is capable of inhibiting carboxyesterase enzymes in those exposed to it. It was discovered that poor work practices had resulted in excessive direct skin contact with isomalathion contained in the malathion solutions. Implementation of good work practices, and the cessation of use of malathion contaminated with isomalathion led to the cessation of poisoning cases.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

A May 2010 study found that in a representative sample of US children, those with higher levels of organophosphate pesticide metabolites in their urine were more likely to have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but no causal relationship was established.[24] Each 10-fold increase in urinary concentration of organophosphate metabolites was associated with a 55% to 72% increase in the odds of ADHD. The study was the first investigation on children's neurodevelopment to be conducted in a group with no particular pesticide exposure.[24][25]

Carcinogenicity

Whether malathion is carcinogenic or not in humans is unknown. Malathion is classified by US EPA as having "suggestive evidence of carcinogenicity but not sufficient to assess human carcinogenic potential."[26] This classification was based on the occurrence of liver tumors at excessive doses in mice and female rats and the presence of rare oral and nasal tumors in rats that occurred following exposure to very large doses. Researchers conducted a study involving participants from six Canadian provinces and found that exposure to organophosphates as a group and malathion alone was associated with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Malathion used as a fumigant was not associated with increased cancer risk. Between 1993 and 1997, as part of the Agricultural Health Study, researchers surveyed 19,717 pesticide applicators about their past pesticide exposures and health histories and no clear association between malathion exposure and cancer was reported.[27]

Amphibians

Although current EPA regulations do not require amphibian testing, a 2008 study done by the University of Pittsburgh found that "cocktails of contaminants", which are frequently found in nature, were lethal to leopard frog tadpoles. They found that a combination of five widely used insecticides (carbaryl, chlorpyrifos, diazinon, endosulfan, and malathion) in concentrations far below the limits set by the EPA killed 99% of leopard frog tadpoles.[28]

See also

References

- ↑ Tomlin, C.D.S. (ed.). The Pesticide Manual - World Compendium, 11th ed., British Crop Protection Council, Surrey, England 1997, p. 755

- ↑ Hansch, C., Leo, A., D. Hoekman. Exploring QSAR - Hydrophobic, Electronic, and Steric Constants. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society., 1995., p. 80

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0375". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Malathion". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ "alanwood.net". Retrieved 2007-09-16.

- ↑ Malathion for mosquito control, US EPA

- ↑ Bonner MR; Coble J; Blair A et al. (2007). "Malathion Exposure and the Incidence of Cancer in the Agricultural Health Study". American Journal of Epidemiology 166 (9): 1023–1034. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm182. PMID 17720683.

- ↑ Edwards JW, Lee SG, Heath LM, Pisaniello DL (2007). "Worker exposure and a risk assessment of malathion and fenthion used in the control of Mediterranean fruit fly in South Australia". Environ. Res. 103 (1): 38–45. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2006.06.001. PMID 16914134.

- ↑ ModelContaminants_Toxic Effec

- ↑ Winnipeg.ca-UD: Public Works: Insect Control Branch

- ↑ Malathion winnipeg

- ↑ National Guideline Clearinghouse | Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pediculosis capitis (head lice) in children and adults 2008

- ↑ Amy J. McMichael; Maria K. Hordinsky (2008). Hair and Scalp Diseases: Medical, Surgical, and Cosmetic Treatments. Informa Health Care. pp. 289–. ISBN 978-1-57444-822-1. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ↑ Downs AM, Stafford KA, Harvey I, Coles GC (1999). "Evidence for double resistance to permethrin and malathion in head lice". Br. J. Dermatol. 141 (3): 508–11. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03046.x. PMID 10583056.

- ↑ Julia A. McMillan; Ralph D. Feigin; Catherine DeAngelis; M. Douglas Jones (1 April 2006). Oski's pediatrics: principles & practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-7817-3894-1. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ↑ British National Formulary 54th Ed. Sept 2007. ISBN 978-0-85369-736-7. ISSN0260-535X

- ↑ "AHFS Drug Information". American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 13 January 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Edwards D (2006). "Reregistration Eligibility Decision for Malathion" (PDF). US Environmental Protection Agency - Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances EPA 738-R-06-030 journal: 9.

- ↑ Maugh II, Thomas H. (16 May 2010). "Study links pesticide to ADHD in children". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "US Department of Health and Human Services: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry - Medical Management Guidelines for Malathion". Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ↑ "California Death Index, 1940-1997 [Database Online]". Provo, Utah: The Generations Network. 2000. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ↑ Bonfante, Jordan (1990-01-08). "Medfly Madness". TIME. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ↑ Baker EL; Warren M; Zack M et al. (1978). "Epidemic malathion poisoning in Pakistan malaria workers". Lancet 1 (8054): 31–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90375-6. PMID 74508.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Bouchard, M. F.; Bellinger, D. C.; Wright, R. O.; Weisskopf, M. G. (2010). "Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Urinary Metabolites of Organophosphate Pesticides". Pediatrics 125 (6): e1270–7. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-3058. PMC 3706632. PMID 20478945.

- ↑ "Organophosphate Pesticides Linked to ADHD". Medscape Today. May 17, 2010. Retrieved Dec 11, 2012.

- ↑ Reregistration Eligibility Decision for Malathion, US EPA

- ↑ Malathion Technical Fact Sheet

- ↑ "Low Concentrations Of Pesticides Can Become Toxic Mixture For Amphibians". Science Daily. November 18, 2008. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

External links

- Malathion Technical Fact Sheet - National Pesticide Information Center

- Malathion General Fact Sheet - National Pesticide Information Center

- Malathion Pesticide Information Profile - Extension Toxicology Network

- ATSDR ToxFAQs

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Re-evaluation of Malathion by the Pest Management Regulatory Agency of Canada

- Malathion in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||