Major depressive disorder

| Major depressive disorder | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | F32, F33 |

| ICD-9 | 296.2, 296.3 |

| OMIM | 608516 |

| DiseasesDB | 3589 |

| MedlinePlus | 003213 |

| eMedicine | med/532 |

| Patient UK | Major depressive disorder |

| MeSH | D003865 |

Major depressive disorder (MDD) (also known as clinical depression, major depression, unipolar depression, or unipolar disorder; or as recurrent depression in the case of repeated episodes) is a mental disorder characterized by a pervasive and persistent low mood that is accompanied by low self-esteem and by a loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities. The term "depression" is used in a number of different ways. It is often used to mean this syndrome but may refer to other mood disorders or simply to a low mood. Major depressive disorder is a disabling condition that adversely affects a person's family, work or school life, sleeping and eating habits, and general health. In the United States, around 3.4% of people with major depression commit suicide, and up to 60% of people who commit suicide had depression or another mood disorder.[1]

The diagnosis of major depressive disorder is based on the patient's self-reported experiences, behavior reported by relatives or friends, and a mental status examination. There is no laboratory test for major depression, although physicians generally request tests for physical conditions that may cause similar symptoms. The most common time of onset is between the ages of 20 and 30 years, with a later peak between 30 and 40 years.[2]

Typically, people are treated with antidepressant medication and, in many cases, also receive counseling, particularly cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).[3] Medication appears to be effective, but the effect may only be significant in the most severely depressed.[4][5] Hospitalization may be necessary in cases with associated self-neglect or a significant risk of harm to self or others. A minority are treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). The course of the disorder varies widely, from one episode lasting weeks to a lifelong disorder with recurrent major depressive episodes. Depressed individuals have shorter life expectancies than those without depression, in part because of greater susceptibility to medical illnesses and suicide. It is unclear whether medications affect the risk of suicide. Current and former patients may be stigmatized.

The understanding of the nature and causes of depression has evolved over the centuries, though this understanding is incomplete and has left many aspects of depression as the subject of discussion and research. Proposed causes include psychological, psycho-social, hereditary, evolutionary and biological factors. Long-term substance abuse may cause or worsen depressive symptoms. Psychological treatments are based on theories of personality, interpersonal communication, and learning. Most biological theories focus on the monoamine chemicals serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine, which are naturally present in the brain and assist communication between nerve cells. This cluster of symptoms (syndrome) was named, described and classified as one of the mood disorders in the 1980 edition of the American Psychiatric Association's diagnostic manual.

Symptoms and signs

Major depression significantly affects a person's family and personal relationships, work or school life, sleeping and eating habits, and general health.[6] Its impact on functioning and well-being has been compared to that of chronic medical conditions such as diabetes.[7]

A person having a major depressive episode usually exhibits a very low mood, which pervades all aspects of life, and an inability to experience pleasure in activities that were formerly enjoyed. Depressed people may be preoccupied with, or ruminate over, thoughts and feelings of worthlessness, inappropriate guilt or regret, helplessness, hopelessness, and self-hatred.[8] In severe cases, depressed people may have symptoms of psychosis. These symptoms include delusions or, less commonly, hallucinations, usually unpleasant.[9] Other symptoms of depression include poor concentration and memory (especially in those with melancholic or psychotic features),[10] withdrawal from social situations and activities, reduced sex drive, and thoughts of death or suicide. Insomnia is common among the depressed. In the typical pattern, a person wakes very early and cannot get back to sleep.[11] Hypersomnia, or oversleeping, can also happen.[11] Some antidepressants may also cause insomnia due to their stimulating effect.[12]

A depressed person may report multiple physical symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, or digestive problems; physical complaints are the most common presenting problem in developing countries, according to the World Health Organization's criteria for depression.[13] Appetite often decreases, with resulting weight loss, although increased appetite and weight gain occasionally occur.[8] Family and friends may notice that the person's behavior is either agitated or lethargic.[11] Older depressed people may have cognitive symptoms of recent onset, such as forgetfulness,[10] and a more noticeable slowing of movements.[14] Depression often coexists with physical disorders common among the elderly, such as stroke, other cardiovascular diseases, Parkinson's disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[15]

Depressed children may often display an irritable mood rather than a depressed mood,[8] and show varying symptoms depending on age and situation.[16] Most lose interest in school and show a decline in academic performance. They may be described as clingy, demanding, dependent, or insecure.[11] Diagnosis may be delayed or missed when symptoms are interpreted as normal moodiness.[8] Depression may also coexist with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), complicating the diagnosis and treatment of both.[17]

Comorbidity

Major depression frequently co-occurs with other psychiatric problems. The 1990–92 National Comorbidity Survey (US) reports that 51% of those with major depression also suffer from lifetime anxiety.[18] Anxiety symptoms can have a major impact on the course of a depressive illness, with delayed recovery, increased risk of relapse, greater disability and increased suicide attempts.[19] American neuroendocrinologist Robert Sapolsky similarly argues that the relationship between stress, anxiety, and depression could be measured and demonstrated biologically.[20] There are increased rates of alcohol and drug abuse and particularly dependence,[21] and around a third of individuals diagnosed with ADHD develop comorbid depression.[22] Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression often co-occur.[6]

Depression and pain often co-occur. One or more pain symptoms are present in 65% of depressed patients, and anywhere from 5 to 85% of patients with pain will be suffering from depression, depending on the setting; there is a lower prevalence in general practice, and higher in specialty clinics. The diagnosis of depression is often delayed or missed, and the outcome worsens. The outcome can also worsen if the depression is noticed but completely misunderstood.[23]

Depression is also associated with a 1.5- to 2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease, independent of other known risk factors, and is itself linked directly or indirectly to risk factors such as smoking and obesity. People with major depression are less likely to follow medical recommendations for treating and preventing cardiovascular disorders, which further increases their risk of medical complications.[24] In addition, cardiologists may not recognize underlying depression that complicates a cardiovascular problem under their care.[25]

Causes

The biopsychosocial model proposes that biological, psychological, and social factors all play a role in causing depression.[26] The diathesis–stress model specifies that depression results when a preexisting vulnerability, or diathesis, is activated by stressful life events. The preexisting vulnerability can be either genetic,[27][28] implying an interaction between nature and nurture, or schematic, resulting from views of the world learned in childhood.[29]

Depression may be directly caused by damage to the cerebellum as is seen in cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome.[30][31][32]

These interactive models have gained empirical support. For example, researchers in New Zealand took a prospective approach to studying depression, by documenting over time how depression emerged among an initially normal cohort of people. The researchers concluded that variation among the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene affects the chances that people who have dealt with very stressful life events will go on to experience depression. To be specific, depression may follow such events, but seems more likely to appear in people with one or two short alleles of the 5-HTT gene.[27] In addition, a Swedish study estimated the heritability of depression—the degree to which individual differences in occurrence are associated with genetic differences—to be around 40% for women and 30% for men,[33] and evolutionary psychologists have proposed that the genetic basis for depression lies deep in the history of naturally selected adaptations. A substance-induced mood disorder resembling major depression has been causally linked to long-term drug use or drug abuse, or to withdrawal from certain sedative and hypnotic drugs.[34][35]

Biological

Monoamine hypothesis

Most antidepressant medications increase the levels of one or more of the monoamines—the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine—in the synaptic cleft between neurons in the brain. Some medications affect the monoamine receptors directly.

Serotonin is hypothesized to regulate other neurotransmitter systems; decreased serotonin activity may allow these systems to act in unusual and erratic ways.[36] According to this "permissive hypothesis", depression arises when low serotonin levels promote low levels of norepinephrine, another monoamine neurotransmitter.[37] Some antidepressants enhance the levels of norepinephrine directly, whereas others raise the levels of dopamine, a third monoamine neurotransmitter. These observations gave rise to the monoamine hypothesis of depression. In its contemporary formulation, the monoamine hypothesis postulates that a deficiency of certain neurotransmitters is responsible for the corresponding features of depression: "Norepinephrine may be related to alertness and energy as well as anxiety, attention, and interest in life; [lack of] serotonin to anxiety, obsessions, and compulsions; and dopamine to attention, motivation, pleasure, and reward, as well as interest in life."[38] The proponents of this theory recommend the choice of an antidepressant with mechanism of action that impacts the most prominent symptoms. Anxious and irritable patients should be treated with SSRIs or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and those experiencing a loss of energy and enjoyment of life with norepinephrine- and dopamine-enhancing drugs.[38]

Besides the clinical observations that drugs that increase the amount of available monoamines are effective antidepressants, recent advances in psychiatric genetics indicate that phenotypic variation in central monoamine function may be marginally associated with vulnerability to depression. Despite these findings, the cause of depression is not simply monoamine deficiency.[39] In the past two decades, research has revealed multiple limitations of the monoamine hypothesis, and its explanatory inadequacy has been highlighted within the psychiatric community.[40] A counterargument is that the mood-enhancing effect of MAO inhibitors and SSRIs takes weeks of treatment to develop, even though the boost in available monoamines occurs within hours. Another counterargument is based on experiments with pharmacological agents that cause depletion of monoamines; while deliberate reduction in the concentration of centrally available monoamines may slightly lower the mood of unmedicated depressed patients, this reduction does not affect the mood of healthy people.[39] The monoamine hypothesis, already limited, has been further oversimplified when presented to the public as a mass marketing tool, usually phrased as a "chemical imbalance".[41]

In 2003 a gene-environment interaction (GxE) was hypothesized to explain why life stress is a predictor for depressive episodes in some individuals, but not in others, depending on an allelic variation of the serotonin-transporter-linked promoter region (5-HTTLPR);[27] a 2009 meta-analysis showed stressful life events were associated with depression, but found no evidence for an association with the 5-HTTLPR genotype.[42] Another 2009 meta-analysis agreed with the latter finding.[43] A 2010 review of studies in this area found a systematic relationship between the method used to assess environmental adversity and the results of the studies; this review also found that both 2009 meta-analyses were significantly biased toward negative studies, which used self-report measures of adversity.[44]

Other hypotheses

MRI scans of patients with depression have revealed a number of differences in brain structure compared to those who are not depressed. Recent meta-analyses of neuroimaging studies in major depression reported that, compared to controls, depressed patients had increased volume of the lateral ventricles and adrenal gland and smaller volumes of the basal ganglia, thalamus, hippocampus, and frontal lobe (including the orbitofrontal cortex and gyrus rectus).[45][46] Hyperintensities have been associated with patients with a late age of onset, and have led to the development of the theory of vascular depression.[47]

There may be a link between depression and neurogenesis of the hippocampus,[48] a center for both mood and memory. Loss of hippocampal neurons is found in some depressed individuals and correlates with impaired memory and dysthymic mood. Drugs may increase serotonin levels in the brain, stimulating neurogenesis and thus increasing the total mass of the hippocampus. This increase may help to restore mood and memory.[49][50] Similar relationships have been observed between depression and an area of the anterior cingulate cortex implicated in the modulation of emotional behavior.[51] One of the neurotrophins responsible for neurogenesis is brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). The level of BDNF in the blood plasma of depressed subjects is drastically reduced (more than threefold) as compared to the norm. Antidepressant treatment increases the blood level of BDNF. Although decreased plasma BDNF levels have been found in many other disorders, there is some evidence that BDNF is involved in the cause of depression and the mechanism of action of antidepressants.[52]

There is some evidence that major depression may be caused in part by an overactive hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) that results in an effect similar to the neuro-endocrine response to stress. Investigations reveal increased levels of the hormone cortisol and enlarged pituitary and adrenal glands, suggesting disturbances of the endocrine system may play a role in some psychiatric disorders, including major depression. Oversecretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone from the hypothalamus is thought to drive this, and is implicated in the cognitive and arousal symptoms.[53]

The hormone estrogen has been implicated in depressive disorders due to the increase in risk of depressive episodes after puberty, the antenatal period, and reduced rates after menopause.[54] On the converse, the premenstrual and postpartum periods of low estrogen levels are also associated with increased risk.[54] Sudden withdrawal of, fluctuations in or periods of sustained low levels of estrogen have been linked to significant mood lowering. Clinical recovery from depression postpartum, perimenopause, and postmenopause was shown to be effective after levels of estrogen were stabilized or restored.[55][56]

Other research has explored potential roles of molecules necessary for overall cellular functioning: cytokines. The symptoms of major depressive disorder are nearly identical to those of sickness behavior, the response of the body when the immune system is fighting an infection. This raises the possibility that depression can result from a maladaptive manifestation of sickness behavior as a result of abnormalities in circulating cytokines.[57] The involvement of pro-inflammatory cytokines in depression is strongly suggested by a meta-analysis of the clinical literature showing higher blood concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α in depressed subjects compared to controls.[58] These immunological abnormalities may cause excessive prostaglandin E₂ production and likely excessive COX-2 expression. Abnormalities in how indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase enzyme activates as well as the metabolism of tryptophan-kynurenine may lead to excessive metabolism of tryptophan-kynurenine and lead to increased production of the neurotoxin quinolinic acid, contributing to major depression. NMDA activation leading to excessive glutamatergic neurotransmission, may also contribute.[59]

Psychological

Various aspects of personality and its development appear to be integral to the occurrence and persistence of depression,[60] with negative emotionality as a common precursor.[61] Although depressive episodes are strongly correlated with adverse events, a person's characteristic style of coping may be correlated with his or her resilience.[62] In addition, low self-esteem and self-defeating or distorted thinking are related to depression. Depression is less likely to occur, as well as quicker to remit, among those who are religious.[63][64][65] It is not always clear which factors are causes and which are effects of depression; however, depressed persons that are able to reflect upon and challenge their thinking patterns often show improved mood and self-esteem.[66]

American psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck, following on from the earlier work of George Kelly and Albert Ellis, developed what is now known as a cognitive model of depression in the early 1960s. He proposed that three concepts underlie depression: a triad of negative thoughts composed of cognitive errors about oneself, one's world, and one's future; recurrent patterns of depressive thinking, or schemas; and distorted information processing.[67] From these principles, he developed the structured technique of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).[68] According to American psychologist Martin Seligman, depression in humans is similar to learned helplessness in laboratory animals, who remain in unpleasant situations when they are able to escape, but do not because they initially learned they had no control.[69]

Attachment theory, which was developed by English psychiatrist John Bowlby in the 1960s, predicts a relationship between depressive disorder in adulthood and the quality of the earlier bond between the infant and the adult caregiver. In particular, it is thought that "the experiences of early loss, separation and rejection by the parent or caregiver (conveying the message that the child is unlovable) may all lead to insecure internal working models ... Internal cognitive representations of the self as unlovable and of attachment figures as unloving [or] untrustworthy would be consistent with parts of Beck's cognitive triad".[70] While a wide variety of studies has upheld the basic tenets of attachment theory, research has been inconclusive as to whether self-reported early attachment and later depression are demonstrably related.[70]

Depressed individuals often blame themselves for negative events,[71] and, as shown in a 1993 study of hospitalized adolescents with self-reported depression, those who blame themselves for negative occurrences may not take credit for positive outcomes.[72] This tendency is characteristic of a depressive attributional, or pessimistic explanatory style.[71] According to Albert Bandura, a Canadian social psychologist associated with social cognitive theory, depressed individuals have negative beliefs about themselves, based on experiences of failure, observing the failure of social models, a lack of social persuasion that they can succeed, and their own somatic and emotional states including tension and stress. These influences may result in a negative self-concept and a lack of self-efficacy; that is, they do not believe they can influence events or achieve personal goals.[73][74]

An examination of depression in women indicates that vulnerability factors—such as early maternal loss, lack of a confiding relationship, responsibility for the care of several young children at home, and unemployment—can interact with life stressors to increase the risk of depression.[75] For older adults, the factors are often health problems, changes in relationships with a spouse or adult children due to the transition to a care-giving or care-needing role, the death of a significant other, or a change in the availability or quality of social relationships with older friends because of their own health-related life changes.[76]

The understanding of depression has also received contributions from the psychoanalytic and humanistic branches of psychology. From the classical psychoanalytic perspective of Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud, depression, or melancholia, may be related to interpersonal loss[77][78] and early life experiences.[79] Existential therapists have connected depression to the lack of both meaning in the present[80] and a vision of the future.[81][82]

Social

Poverty and social isolation are associated with increased risk of mental health problems in general.[60] Child abuse (physical, emotional, sexual, or neglect) is also associated with increased risk of developing depressive disorders later in life.[83] Such a link has good face validity given that it is during the years of development that a child is learning how to become a social being. Abuse of the child by the caregiver is bound to distort the developing personality and create a much greater risk for depression and many other debilitating mental and emotional states. Disturbances in family functioning, such as parental (particularly maternal) depression, severe marital conflict or divorce, death of a parent, or other disturbances in parenting are additional risk factors.[60] In adulthood, stressful life events are strongly associated with the onset of major depressive episodes.[84] In this context, life events connected to social rejection appear to be particularly related to depression.[85][86] Evidence that a first episode of depression is more likely to be immediately preceded by stressful life events than are recurrent ones is consistent with the hypothesis that people may become increasingly sensitized to life stress over successive recurrences of depression.[87][88]

The relationship between stressful life events and social support has been a matter of some debate; the lack of social support may increase the likelihood that life stress will lead to depression, or the absence of social support may constitute a form of strain that leads to depression directly.[89] There is evidence that neighborhood social disorder, for example, due to crime or illicit drugs, is a risk factor, and that a high neighborhood socioeconomic status, with better amenities, is a protective factor.[90] Adverse conditions at work, particularly demanding jobs with little scope for decision-making, are associated with depression, although diversity and confounding factors make it difficult to confirm that the relationship is causal.[91]

Depression can be caused by prejudice. This can occur when people hold negative self-stereotypes about themselves. This "deprejudice" can be related to a group membership (e.g., Me-Gay-Bad) or not (Me-Bad). If someone has prejudicial beliefs about a stigmatized group and then becomes a member of that group, they may internalize their prejudice and develop depression. For example, a boy growing up in the United States may learn the negative stereotype that gay men are immoral. When he grows up and realizes he is gay, he may direct this prejudice inward on himself and become depressed. People may also show prejudice internalization through self-stereotyping because of negative childhood experiences such as verbal and physical abuse.[92]

Evolutionary

From the standpoint of evolutionary theory, major depression is hypothesized, in some instances, to increase an individual's reproductive fitness. Evolutionary approaches to depression and evolutionary psychology posit specific mechanisms by which depression may have been genetically incorporated into the human gene pool, accounting for the high heritability and prevalence of depression by proposing that certain components of depression are adaptations,[93] such as the behaviors relating to attachment and social rank.[94] Current behaviors can be explained as adaptations to regulate relationships or resources, although the result may be maladaptive in modern environments.[95]

From another viewpoint, a counseling therapist may see depression not as a biochemical illness or disorder but as "a species-wide evolved suite of emotional programs that are mostly activated by a perception, almost always over-negative, of a major decline in personal usefulness, that can sometimes be linked to guilt, shame or perceived rejection".[96] This suite may have manifested in aging hunters in humans' foraging past, who were marginalized by their declining skills, and may continue to appear in alienated members of today's society. The feelings of uselessness generated by such marginalization could in theory prompt support from friends and kin. In addition, in a manner analogous to that in which physical pain has evolved to hinder actions that may cause further injury, "psychic misery" may have evolved to prevent hasty and maladaptive reactions to distressing situations.[97]

Drug and alcohol use

Very high levels of substance abuse occur in the psychiatric population, especially alcohol, sedatives and cannabis. Depression and other mental health problems can have a substance induced cause; making a differential or dual diagnosis regarding whether mental ill-health is substance related or not or co-occurring is an important part of a psychiatric evaluation.[98] According to the DSM-IV, a diagnosis of mood disorder cannot be made if the cause is believed to be due to "the direct physiological effects of a substance"; when a syndrome resembling major depression is believed to be caused immediately by substance abuse or by an adverse drug reaction, it is referred to as, "substance-induced mood disturbance". Alcoholism or excessive alcohol consumption significantly increases the risk of developing major depression.[99][100] Like alcohol, the benzodiazepines are central nervous system depressants; this class of medication is commonly used to treat insomnia, anxiety, and muscular spasms. Similar to alcohol, benzodiazepines increase the risk of developing major depression. This increased risk of depression may be due in part to the adverse or toxic effects of sedative-hypnotic drugs including alcohol on neurochemistry,[100] such as decreased levels of serotonin and norepinephrine,[35] or activation of immune mediated inflammatory pathways in the brain.[101] Chronic use of benzodiazepines also can cause or worsen depression,[102] or depression may be part of a protracted withdrawal syndrome.[103][104] About a quarter of people recovering from alcoholism experience anxiety and depression, which can persist for up to 2 years.[105] Methamphetamine abuse is also commonly associated with depression.[106]

Diagnosis

Clinical assessment

A diagnostic assessment may be conducted by a suitably trained general practitioner, or by a psychiatrist or psychologist,[6] who records the person's current circumstances, biographical history, current symptoms, and family history. The broad clinical aim is to formulate the relevant biological, psychological, and social factors that may be impacting on the individual's mood. The assessor may also discuss the person's current ways of regulating mood (healthy or otherwise) such as alcohol and drug use. The assessment also includes a mental state examination, which is an assessment of the person's current mood and thought content, in particular the presence of themes of hopelessness or pessimism, self-harm or suicide, and an absence of positive thoughts or plans.[6] Specialist mental health services are rare in rural areas, and thus diagnosis and management is left largely to primary-care clinicians.[107] This issue is even more marked in developing countries.[108] The mental health examination may include the use of a rating scale such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression[109] or the Beck Depression Inventory.[110] The score on a rating scale alone is insufficient to diagnose depression to the satisfaction of the DSM or ICD, but it provides an indication of the severity of symptoms for a time period, so a person who scores above a given cut-off point can be more thoroughly evaluated for a depressive disorder diagnosis.[111] Several rating scales are used for this purpose.[111] Screening programs have been advocated to improve detection of depression, but there is evidence that they do not improve detection rates, treatment, or outcome.[112]

Primary-care physicians and other non-psychiatrist physicians have difficulty diagnosing depression, in part because they are trained to recognize and treat physical symptoms, and depression can cause myriad physical (psychosomatic) symptoms. Non-psychiatrists miss two-thirds of cases and unnecessarily treat other patients.[113][114]

Before diagnosing a major depressive disorder, in general a doctor performs a medical examination and selected investigations to rule out other causes of symptoms. These include blood tests measuring TSH and thyroxine to exclude hypothyroidism; basic electrolytes and serum calcium to rule out a metabolic disturbance; and a full blood count including ESR to rule out a systemic infection or chronic disease.[114] Adverse affective reactions to medications or alcohol misuse are often ruled out, as well. Testosterone levels may be evaluated to diagnose hypogonadism, a cause of depression in men.[115]

Subjective cognitive complaints appear in older depressed people, but they can also be indicative of the onset of a dementing disorder, such as Alzheimer's disease.[116][117] Cognitive testing and brain imaging can help distinguish depression from dementia.[118] A CT scan can exclude brain pathology in those with psychotic, rapid-onset or otherwise unusual symptoms.[119] In general, investigations are not repeated for a subsequent episode unless there is a medical indication.

No biological tests confirm major depression.[120] Biomarkers of depression have been sought to provide an objective method of diagnosis. There are several potential biomarkers, including Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and various functional MRI techniques. One study developed a decision tree model of interpreting a series of fMRI scans taken during various activities. In their subjects, the authors of that study were able to achieve a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 87%, corresponding to a negative predictive value of 98% and a positive predictive value of 32% (positive and negative likelihood ratios were 6.15, 0.23, respectively). However, much more research is needed before these tests could be used clinically.[121]

DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 criteria

The most widely used criteria for diagnosing depressive conditions are found in the American Psychiatric Association's revised fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR), and the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), which uses the name depressive episode for a single episode and recurrent depressive disorder for repeated episodes.[122] The latter system is typically used in European countries, while the former is used in the US and many other non-European nations,[123] and the authors of both have worked towards conforming one with the other.[124]

Both DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 mark out typical (main) depressive symptoms.[125] ICD-10 defines three typical depressive symptoms (depressed mood, anhedonia, and reduced energy), two of which should be present to determine depressive disorder diagnosis.[126][127] According to DSM-IV-TR, there are two main depressive symptoms—depressed mood and anhedonia. At least one of these must be present to make a diagnosis of major depressive episode.[128]

Major depressive disorder is classified as a mood disorder in DSM-IV-TR.[129] The diagnosis hinges on the presence of single or recurrent major depressive episodes.[8] Further qualifiers are used to classify both the episode itself and the course of the disorder. The category Depressive Disorder Not Otherwise Specified is diagnosed if the depressive episode's manifestation does not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode. The ICD-10 system does not use the term major depressive disorder but lists very similar criteria for the diagnosis of a depressive episode (mild, moderate or severe); the term recurrent may be added if there have been multiple episodes without mania.[122]

Major depressive episode

A major depressive episode is characterized by the presence of a severely depressed mood that persists for at least two weeks.[8] Episodes may be isolated or recurrent and are categorized as mild (few symptoms in excess of minimum criteria), moderate, or severe (marked impact on social or occupational functioning). An episode with psychotic features—commonly referred to as psychotic depression—is automatically rated as severe. If the patient has had an episode of mania or markedly elevated mood, a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is made instead.[130] Depression without mania is sometimes referred to as unipolar because the mood remains at one emotional state or "pole".[131]

DSM-IV-TR excludes cases where the symptoms are a result of bereavement, although it is possible for normal bereavement to evolve into a depressive episode if the mood persists and the characteristic features of a major depressive episode develop.[132] The criteria have been criticized because they do not take into account any other aspects of the personal and social context in which depression can occur.[133] In addition, some studies have found little empirical support for the DSM-IV cut-off criteria, indicating they are a diagnostic convention imposed on a continuum of depressive symptoms of varying severity and duration:[134] Excluded are a range of related diagnoses, including dysthymia, which involves a chronic but milder mood disturbance;[135] recurrent brief depression, consisting of briefer depressive episodes;[136][137] minor depressive disorder, whereby only some symptoms of major depression are present;[138] and adjustment disorder with depressed mood, which denotes low mood resulting from a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor.[139]

Subtypes

The DSM-IV-TR recognizes five further subtypes of MDD, called specifiers, in addition to noting the length, severity and presence of psychotic features:

- Melancholic depression is characterized by a loss of pleasure in most or all activities, a failure of reactivity to pleasurable stimuli, a quality of depressed mood more pronounced than that of grief or loss, a worsening of symptoms in the morning hours, early-morning waking, psychomotor retardation, excessive weight loss (not to be confused with anorexia nervosa), or excessive guilt.[140]

- Atypical depression is characterized by mood reactivity (paradoxical anhedonia) and positivity, significant weight gain or increased appetite (comfort eating), excessive sleep or sleepiness (hypersomnia), a sensation of heaviness in limbs known as leaden paralysis, and significant social impairment as a consequence of hypersensitivity to perceived interpersonal rejection.[141]

- Catatonic depression is a rare and severe form of major depression involving disturbances of motor behavior and other symptoms. Here, the person is mute and almost stuporous, and either remains immobile or exhibits purposeless or even bizarre movements. Catatonic symptoms also occur in schizophrenia or in manic episodes, or may be caused by neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[142]

- Postpartum depression, or mental and behavioral disorders associated with the puerperium, not elsewhere classified,[122] refers to the intense, sustained and sometimes disabling depression experienced by women after giving birth. Postpartum depression has an incidence rate of 10–15% among new mothers. The DSM-IV mandates that, in order to qualify as postpartum depression, onset occur within one month of delivery. It has been said that postpartum depression can last as long as three months.[143]

- Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a form of depression in which depressive episodes come on in the autumn or winter, and resolve in spring. The diagnosis is made if at least two episodes have occurred in colder months with none at other times, over a two-year period or longer.[144]

Differential diagnoses

To confer major depressive disorder as the most likely diagnosis, other potential diagnoses must be considered, including dysthymia, adjustment disorder with depressed mood, or bipolar disorder. Dysthymia is a chronic, milder mood disturbance in which a person reports a low mood almost daily over a span of at least two years. The symptoms are not as severe as those for major depression, although people with dysthymia are vulnerable to secondary episodes of major depression (sometimes referred to as double depression).[135] Adjustment disorder with depressed mood is a mood disturbance appearing as a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor, in which the resulting emotional or behavioral symptoms are significant but do not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode.[139] Bipolar disorder, also known as manic–depressive disorder, is a condition in which depressive phases alternate with periods of mania or hypomania. Although depression is currently categorized as a separate disorder, there is ongoing debate because individuals diagnosed with major depression often experience some hypomanic symptoms, indicating a mood disorder continuum.[145]

Other disorders need to be ruled out before diagnosing major depressive disorder. They include depressions due to physical illness, medications, and substance abuse. Depression due to physical illness is diagnosed as a mood disorder due to a general medical condition. This condition is determined based on history, laboratory findings, or physical examination. When the depression is caused by a substance abused including a drug of abuse, a medication, or exposure to a toxin, it is then diagnosed as a substance-induced mood disorder.[146]

Prevention

Behavioral interventions, such as interpersonal therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, are effective at preventing new onset depression.[147][148][149] Because such interventions appear to be most effective when delivered to individuals or small groups, it has been suggested that they may be able to reach their large target audience most efficiently through the Internet.[150]

However, an earlier meta-analysis found preventive programs with a competence-enhancing component to be superior to behavior-oriented programs overall, and found behavioral programs to be particularly unhelpful for older people, for whom social support programs were uniquely beneficial. In addition, the programs that best prevented depression comprised more than eight sessions, each lasting between 60 and 90 minutes, were provided by a combination of lay and professional workers, had a high-quality research design, reported attrition rates, and had a well-defined intervention.[151]

The Netherlands mental health care system provides preventive interventions, such as the "Coping with Depression" course (CWD) for people with sub-threshold depression. The course is claimed to be the most successful of psychoeducational interventions for the treatment and prevention of depression (both for its adaptability to various populations and its results), with a risk reduction of 38% in major depression and an efficacy as a treatment comparing favorably to other psychotherapies.[147][152] Preventative efforts may result in decreases in rates of the condition of between 22 and 38%.[149]

Management

The three most common treatments for depression are psychotherapy, medication, and electroconvulsive therapy. Psychotherapy is the treatment of choice (over medication) for people under 18. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2004 guidelines indicate that antidepressants should not be used for the initial treatment of mild depression, because the risk-benefit ratio is poor. The guidelines recommend that antidepressants treatment in combination with psychosocial interventions should be considered for:

- People with a past history of moderate or severe depression

- Those with mild depression that has been present for a long period

- As a second line treatment for mild depression that persists after other interventions

- As a first line treatment for moderate or severe depression.

The guidelines further note that antidepressant treatment should be continued for at least six months to reduce the risk of relapse, and that SSRIs are better tolerated than tricyclic antidepressants.[153]

American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines recommend that initial treatment should be individually tailored based on factors including severity of symptoms, co-existing disorders, prior treatment experience, and patient preference. Options may include pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or light therapy. Antidepressant medication is recommended as an initial treatment choice in people with mild, moderate, or severe major depression, and should be given to all patients with severe depression unless ECT is planned.[154]

Treatment options are much more limited in developing countries, where access to mental health staff, medication, and psychotherapy is often difficult. Development of mental health services is minimal in many countries; depression is viewed as a phenomenon of the developed world despite evidence to the contrary, and not as an inherently life-threatening condition.[155] A 2014 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of psychological versus medical therapy in children.[156]

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy can be delivered, to individuals, groups, or families by mental health professionals, including psychotherapists, psychiatrists, psychologists, clinical social workers, counselors, and suitably trained psychiatric nurses. With more complex and chronic forms of depression, a combination of medication and psychotherapy may be used.[157][158] A 2012 review found psychotherapy to be better than no treatment but not other treatments.[159]

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) currently has the most research evidence for the treatment of depression in children and adolescents, and CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) are preferred therapies for adolescent depression.[160] In people under 18, according to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, medication should be offered only in conjunction with a psychological therapy, such as CBT, interpersonal therapy, or family therapy.[161]

Psychotherapy has been shown to be effective in older people.[162][163] Successful psychotherapy appears to reduce the recurrence of depression even after it has been terminated or replaced by occasional booster sessions.

The most-studied form of psychotherapy for depression is CBT, which teaches clients to challenge self-defeating, but enduring ways of thinking (cognitions) and change counter-productive behaviors. Research beginning in the mid-1990s suggested that CBT could perform as well or as better than antidepressants in patients with moderate to severe depression.[164][165] CBT may be effective in depressed adolescents,[166] although its effects on severe episodes are not definitively known.[167] Several variables predict success for cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents: higher levels of rational thoughts, less hopelessness, fewer negative thoughts, and fewer cognitive distortions.[168] CBT is particularly beneficial in preventing relapse.[169][170] Several variants of cognitive behavior therapy have been used in those with depression, the most notable being rational emotive behavior therapy,[171] and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.[172] Mindfulness based stress reduction programs may reduce depression symptoms.[173][174] Mindfulness programs also appear to be a promising intervention in youth.[175]

Psychoanalysis is a school of thought, founded by Sigmund Freud, which emphasizes the resolution of unconscious mental conflicts.[176] Psychoanalytic techniques are used by some practitioners to treat clients presenting with major depression.[177] A more widely practiced, eclectic technique, called psychodynamic psychotherapy, is loosely based on psychoanalysis and has an additional social and interpersonal focus.[178] In a meta-analysis of three controlled trials of Short Psychodynamic Supportive Psychotherapy, this modification was found to be as effective as medication for mild to moderate depression.[179]

Logotherapy, a form of existential psychotherapy developed by Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, addresses the filling of an "existential vacuum" associated with feelings of futility and meaninglessness. It is posited that this type of psychotherapy may be useful for depression in older adolescents.[180]

Antidepressants

Conflicting results have arisen from studies look at the effectiveness of antidepressants in people with acute mild to moderate depression. Stronger evidence supports the usefulness of antidepressants in the treatment of depression that is chronic (dysthymia) or severe.

While small benefits were found researchers Irving Kirsch and Thomas Moore state they may be due to issues with the trials rather than a true effect of the medication.[182] In a later publication, Kirsch concluded that the overall effect of new-generation antidepressant medication is below recommended criteria for clinical significance.[5] Similar results were obtained in a meta analysis by Fornier.[4]

A review commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence concluded that there is strong evidence that SSRIs have greater efficacy than placebo on achieving a 50% reduction in depression scores in moderate and severe major depression, and that there is some evidence for a similar effect in mild depression.[183] Similarly, a Cochrane systematic review of clinical trials of the generic antidepressant amitriptyline concluded that there is strong evidence that its efficacy is superior to placebo.[184]

In 2014 the U.S. FDA published a systematic review of all antidepressant maintenance trials submitted to the agency between 1985 and 2012. The authors concluded that maintenance treatment reduced the risk of relapse by 52% compared to placebo, and that this effect was primarily due to recurrent depression in the placebo group rather than a drug withdrawal effect.[4]

To find the most effective antidepressant medication with minimal side-effects, the dosages can be adjusted, and if necessary, combinations of different classes of antidepressants can be tried. Response rates to the first antidepressant administered range from 50–75%, and it can take at least six to eight weeks from the start of medication to remission.[185] Antidepressant medication treatment is usually continued for 16 to 20 weeks after remission, to minimize the chance of recurrence,[185] and even up to one year of continuation is recommended.[186] People with chronic depression may need to take medication indefinitely to avoid relapse.[6]

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the primary medications prescribed, owing to their relatively mild side-effects, and because they are less toxic in overdose than other antidepressants.[187] Patients who do not respond to one SSRI can be switched to another antidepressant, and this results in improvement in almost 50% of cases.[188] Another option is to switch to the atypical antidepressant bupropion.[189] Venlafaxine, an antidepressant with a different mechanism of action, may be modestly more effective than SSRIs.[190] However, venlafaxine is not recommended in the UK as a first-line treatment because of evidence suggesting its risks may outweigh benefits,[191] and it is specifically discouraged in children and adolescents.[192][193]

For adolescent depression, fluoxetine is recommended[192] Antidepressants appear to have only slight benefit in children.[194] There is also insufficient evidence to determine effectiveness in those with depression complicated by dementia.[195] Any antidepressant can cause low serum sodium levels (also called hyponatremia);[196] nevertheless, it has been reported more often with SSRIs.[187] It is not uncommon for SSRIs to cause or worsen insomnia; the sedating antidepressant mirtazapine can be used in such cases.[197][198]

Irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors, an older class of antidepressants, have been plagued by potentially life-threatening dietary and drug interactions. They are still used only rarely, although newer and better-tolerated agents of this class have been developed.[199] The safety profile is different with reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors such as moclobemide where the risk of serious dietary interactions is negligible and dietary restrictions are less strict.[200]

For children, adolescents, and probably young adults between 18 and 24 years old, there is a higher risk of both suicidal ideations and suicidal behavior in those treated with SSRIs.[201][202] For adults, it is unclear whether SSRIs affect the risk of suicidality.[202] One review found no connection;[203] another an increased risk;[204] and a third no risk in those 25–65 years old and a decrease risk in those more than 65.[205] A black box warning was introduced in the United States in 2007 on SSRI and other antidepressant medications due to increased risk of suicide in patients younger than 24 years old.[206] Similar precautionary notice revisions were implemented by the Japanese Ministry of Health.[207]

Other medications

There is some evidence that fish oil supplements containing high levels of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) may be effective in major depression,[208] but other meta-analysis of the research conclude that positive effects may be due to publication bias.[209] There is some preliminary evidence that COX-2 inhibitors have a beneficial effect on major depression.[59] Lithium appears effective at lowering the risk of suicide in those with bipolar disorder and unipolar depression to nearly the same levels as the general population.[210] There is a narrow range of effective and safe dosages of lithium thus close monitoring may be needed.[211] Low-dose thyroid hormone may be added to existing antidepressants to treat persistent depression symptoms in people who have tried multiple courses of medication.[212]

Electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a standard psychiatric treatment in which seizures are electrically induced in patients to provide relief from psychiatric illnesses.[213]:1880 ECT is used with informed consent[214] as a last line of intervention for major depressive disorder.[215]

A round of ECT is effective for about 50% of people with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, whether it is unipolar or bipolar.[216] Followup treatment is still poorly studied, but about half of people who respond, relapse with twelve months.[217]

Aside from effects in the brain, the general physical risks of ECT are similar to those of brief general anesthesia.[218]:259 Immediately following treatment, the most common adverse effects are confusion and memory loss.[215][219] ECT is considered one of the least harmful treatment options available for severely depressed pregnant women.[220]

A usual course of ECT involves multiple administrations, typically given two or three times per week until the patient is no longer suffering symptoms ECT is administered under anesthetic with a muscle relaxant.[221] Electroconvulsive therapy can differ in its application in three ways: electrode placement, frequency of treatments, and the electrical waveform of the stimulus. These three forms of application have significant differences in both adverse side effects and symptom remission. After treatment, drug therapy is usually continued, and some patients receive maintenance ECT.[215]

ECT appears to work in the short term via an anticonvulsant effect mostly in the frontal lobes, and longer term via neurotrophic effects primarily in the medial temporal lobe.[222]

Other

Bright light therapy reduces depression symptom severity, with benefit was found for both seasonal affective disorder and for nonseasonal depression, and an effect similar to those for conventional antidepressants. For non-seasonal depression, adding light therapy to the standard antidepressant treatment was not effective.[223] For non-seasonal depression where light was used mostly in combination with antidepressants or wake therapy a moderate effect was found, with response better than control treatment in high-quality studies, in studies that applied morning light treatment, and with people who respond to total or partial sleep deprivation.[224] Both analyses noted poor quality, short duration, and small size of most of the reviewed studies.

There is a small amount of evidence that skipping a night's sleep may help.[225] Physical exercise is recommended for management of mild depression,[226] and has a moderate effect on symptoms.[227] It is equivalent to the use of medications or psychological therapies in most people.[227] In the older people it does appear to decrease depression.[228] In unblinded, non-randomized observational studies Smoking cessation has benefits in depression as large as or larger than those of medications.[229] Cognitive behavioral therapy and occupational programs (including modification of work activities and assistance) have been shown to be effective in reducing sick days taken by workers with depression.[230]

Prognosis

Major depressive episodes often resolve over time whether or not they are treated. Outpatients on a waiting list show a 10–15% reduction in symptoms within a few months, with approximately 20% no longer meeting the full criteria for a depressive disorder.[231] The median duration of an episode has been estimated to be 23 weeks, with the highest rate of recovery in the first three months.[232]

Studies have shown that 80% of those suffering from their first major depressive episode will suffer from at least 1 more during their life,[233] with a lifetime average of 4 episodes.[234] Other general population studies indicate that around half those who have an episode recover (whether treated or not) and remain well, while the other half will have at least one more, and around 15% of those experience chronic recurrence.[235] Studies recruiting from selective inpatient sources suggest lower recovery and higher chronicity, while studies of mostly outpatients show that nearly all recover, with a median episode duration of 11 months. Around 90% of those with severe or psychotic depression, most of whom also meet criteria for other mental disorders, experience recurrence.[236][237]

Recurrence is more likely if symptoms have not fully resolved with treatment. Current guidelines recommend continuing antidepressants for four to six months after remission to prevent relapse. Evidence from many randomized controlled trials indicates continuing antidepressant medications after recovery can reduce the chance of relapse by 70% (41% on placebo vs. 18% on antidepressant). The preventive effect probably lasts for at least the first 36 months of use.[238]

Those people experiencing repeated episodes of depression require ongoing treatment in order to prevent more severe, long-term depression. In some cases, people must take medications for long periods of time or for the rest of their lives.[239]

Cases when outcome is poor are associated with inappropriate treatment, severe initial symptoms that may include psychosis, early age of onset, more previous episodes, incomplete recovery after 1 year, pre-existing severe mental or medical disorder, and family dysfunction as well.[240]

Depressed individuals have a shorter life expectancy than those without depression, in part because depressed patients are at risk of dying by suicide.[241] However, they also have a higher rate of dying from other causes,[242] being more susceptible to medical conditions such as heart disease.[243] Up to 60% of people who commit suicide have a mood disorder such as major depression, and the risk is especially high if a person has a marked sense of hopelessness or has both depression and borderline personality disorder.[1] The lifetime risk of suicide associated with a diagnosis of major depression in the US is estimated at 3.4%, which averages two highly disparate figures of almost 7% for men and 1% for women[244] (although suicide attempts are more frequent in women).[245] The estimate is substantially lower than a previously accepted figure of 15%, which had been derived from older studies of hospitalized patients.[246]

Depression is often associated with unemployment and poverty.[247] Major depression is currently the leading cause of disease burden in North America and other high-income countries, and the fourth-leading cause worldwide. In the year 2030, it is predicted to be the second-leading cause of disease burden worldwide after HIV, according to the World Health Organization.[248] Delay or failure in seeking treatment after relapse, and the failure of health professionals to provide treatment, are two barriers to reducing disability.[249]

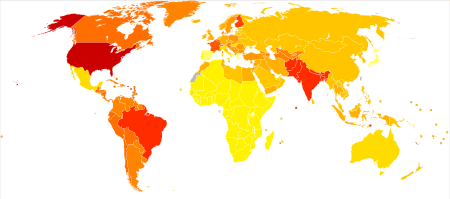

Epidemiology

no data

<700

700–775

775–850

850–925

925–1000

1000–1075

|

1075–1150

1150–1225

1225–1300

1300–1375

1375–1450

>1450

|

Depression is a major cause of morbidity worldwide.[251] It is believed to currently affect approximately 298 million people as of 2010 (4.3% of the global population).[252] Lifetime prevalence varies widely, from 3% in Japan to 17% in the US.[253] In most countries the number of people who have depression during their lives falls within an 8–12% range.[253] In North America, the probability of having a major depressive episode within a year-long period is 3–5% for males and 8–10% for females.[254][255] Population studies have consistently shown major depression to be about twice as common in women as in men, although it is unclear why this is so, and whether factors unaccounted for are contributing to this.[256] The relative increase in occurrence is related to pubertal development rather than chronological age, reaches adult ratios between the ages of 15 and 18, and appears associated with psychosocial more than hormonal factors.[256]

People are most likely to suffer their first depressive episode between the ages of 30 and 40, and there is a second, smaller peak of incidence between ages 50 and 60.[257] The risk of major depression is increased with neurological conditions such as stroke, Parkinson's disease, or multiple sclerosis, and during the first year after childbirth.[258] It is also more common after cardiovascular illnesses, and is related more to a poor outcome than to a better one.[243][259] Studies conflict on the prevalence of depression in the elderly, but most data suggest there is a reduction in this age group.[260] Depressive disorders are more common to observe in urban than in rural population and the prevalence is in groups with stronger socioeconomic factors i.e. homelessness.[261]

History

The Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates described a syndrome of melancholia as a distinct disease with particular mental and physical symptoms; he characterized all "fears and despondencies, if they last a long time" as being symptomatic of the ailment.[262] It was a similar but far broader concept than today's depression; prominence was given to a clustering of the symptoms of sadness, dejection, and despondency, and often fear, anger, delusions and obsessions were included.[79]

The term depression itself was derived from the Latin verb deprimere, "to press down".[263] From the 14th century, "to depress" meant to subjugate or to bring down in spirits. It was used in 1665 in English author Richard Baker's Chronicle to refer to someone having "a great depression of spirit", and by English author Samuel Johnson in a similar sense in 1753.[264] The term also came into use in physiology and economics. An early usage referring to a psychiatric symptom was by French psychiatrist Louis Delasiauve in 1856, and by the 1860s it was appearing in medical dictionaries to refer to a physiological and metaphorical lowering of emotional function.[265] Since Aristotle, melancholia had been associated with men of learning and intellectual brilliance, a hazard of contemplation and creativity. The newer concept abandoned these associations and through the 19th century, became more associated with women.[79]

Although melancholia remained the dominant diagnostic term, depression gained increasing currency in medical treatises and was a synonym by the end of the century; German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin may have been the first to use it as the overarching term, referring to different kinds of melancholia as depressive states.[266]

Sigmund Freud likened the state of melancholia to mourning in his 1917 paper Mourning and Melancholia. He theorized that objective loss, such as the loss of a valued relationship through death or a romantic break-up, results in subjective loss as well; the depressed individual has identified with the object of affection through an unconscious, narcissistic process called the libidinal cathexis of the ego. Such loss results in severe melancholic symptoms more profound than mourning; not only is the outside world viewed negatively but the ego itself is compromised.[77] The patient's decline of self-perception is revealed in his belief of his own blame, inferiority, and unworthiness.[78] He also emphasized early life experiences as a predisposing factor.[79] Adolf Meyer put forward a mixed social and biological framework emphasizing reactions in the context of an individual's life, and argued that the term depression should be used instead of melancholia.[267] The first version of the DSM (DSM-I, 1952) contained depressive reaction and the DSM-II (1968) depressive neurosis, defined as an excessive reaction to internal conflict or an identifiable event, and also included a depressive type of manic-depressive psychosis within Major affective disorders.[268]

In the mid-20th century, researchers theorized that depression was caused by a chemical imbalance in neurotransmitters in the brain, a theory based on observations made in the 1950s of the effects of reserpine and isoniazid in altering monoamine neurotransmitter levels and affecting depressive symptoms.[269]

The term "unipolar" (along with the related term "bipolar") was coined by the neurologist and psychiatrist Karl Kleist, and subsequently used by his disciples Edda Neele and Karl Leonhard.[270]

The term Major depressive disorder was introduced by a group of US clinicians in the mid-1970s as part of proposals for diagnostic criteria based on patterns of symptoms (called the "Research Diagnostic Criteria", building on earlier Feighner Criteria),[271] and was incorporated into the DSM-III in 1980.[272] To maintain consistency the ICD-10 used the same criteria, with only minor alterations, but using the DSM diagnostic threshold to mark a mild depressive episode, adding higher threshold categories for moderate and severe episodes.[125][272] The ancient idea of melancholia still survives in the notion of a melancholic subtype.

The new definitions of depression were widely accepted, albeit with some conflicting findings and views. There have been some continued empirically based arguments for a return to the diagnosis of melancholia.[273][274] There has been some criticism of the expansion of coverage of the diagnosis, related to the development and promotion of antidepressants and the biological model since the late 1950s.[275]

Society and culture

People's conceptualizations of depression vary widely, both within and among cultures. "Because of the lack of scientific certainty," one commentator has observed, "the debate over depression turns on questions of language. What we call it—'disease,' 'disorder,' 'state of mind'—affects how we view, diagnose, and treat it."[277] There are cultural differences in the extent to which serious depression is considered an illness requiring personal professional treatment, or is an indicator of something else, such as the need to address social or moral problems, the result of biological imbalances, or a reflection of individual differences in the understanding of distress that may reinforce feelings of powerlessness, and emotional struggle.[278][279]

The diagnosis is less common in some countries, such as China. It has been argued that the Chinese traditionally deny or somatize emotional depression (although since the early 1980s, the Chinese denial of depression may have modified drastically).[280] Alternatively, it may be that Western cultures reframe and elevate some expressions of human distress to disorder status. Australian professor Gordon Parker and others have argued that the Western concept of depression "medicalizes" sadness or misery.[281][282] Similarly, Hungarian-American psychiatrist Thomas Szasz and others argue that depression is a metaphorical illness that is inappropriately regarded as an actual disease.[283] There has also been concern that the DSM, as well as the field of descriptive psychiatry that employs it, tends to reify abstract phenomena such as depression, which may in fact be social constructs.[284] American archetypal psychologist James Hillman writes that depression can be healthy for the soul, insofar as "it brings refuge, limitation, focus, gravity, weight, and humble powerlessness."[285] Hillman argues that therapeutic attempts to eliminate depression echo the Christian theme of resurrection, but have the unfortunate effect of demonizing a soulful state of being.

Historical figures were often reluctant to discuss or seek treatment for depression due to social stigma about the condition, or due to ignorance of diagnosis or treatments. Nevertheless, analysis or interpretation of letters, journals, artwork, writings, or statements of family and friends of some historical personalities has led to the presumption that they may have had some form of depression. People who may have had depression include English author Mary Shelley,[286] American-British writer Henry James,[287] and American president Abraham Lincoln.[288] Some well-known contemporary people with possible depression include Canadian songwriter Leonard Cohen[289] and American playwright and novelist Tennessee Williams.[290] Some pioneering psychologists, such as Americans William James[291][292] and John B. Watson,[293] dealt with their own depression.

There has been a continuing discussion of whether neurological disorders and mood disorders may be linked to creativity, a discussion that goes back to Aristotelian times.[294][295] British literature gives many examples of reflections on depression.[296] English philosopher John Stuart Mill experienced a several-months-long period of what he called "a dull state of nerves", when one is "unsusceptible to enjoyment or pleasurable excitement; one of those moods when what is pleasure at other times, becomes insipid or indifferent". He quoted English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Dejection" as a perfect description of his case: "A grief without a pang, void, dark and drear, / A drowsy, stifled, unimpassioned grief, / Which finds no natural outlet or relief / In word, or sigh, or tear."[297][298] English writer Samuel Johnson used the term "the black dog" in the 1780s to describe his own depression,[299] and it was subsequently popularized by depression sufferer former British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill.[299]

Social stigma of major depression is widespread, and contact with mental health services reduces this only slightly. Public opinions on treatment differ markedly to those of health professionals; alternative treatments are held to be more helpful than pharmacological ones, which are viewed poorly.[300] In the UK, the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Royal College of General Practitioners conducted a joint Five-year Defeat Depression campaign to educate and reduce stigma from 1992 to 1996;[301] a MORI study conducted afterwards showed a small positive change in public attitudes to depression and treatment.[302]

Other animals

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Barlow 2005, pp. 248–49

- ↑ "Major Depressive Disorder". American Medical Network, Inc. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ↑ Driessen, Ellen; Hollon, Steven D. (2010). "Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Mood Disorders: Efficacy, Moderators and Mediators". Psychiatric Clinics of North America 33 (3): 537–55.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J (January 2010). "Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis". JAMA 303 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1943. PMC 3712503. PMID 20051569.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT (February 2008). "Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration". PLoS Med. 5 (2): e45. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. PMC 2253608. PMID 18303940.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Depression (PDF). National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Rogers W, Spritzer K (1995). "Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses". Archives of General Psychiatry 52 (1): 11–19. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950130011002. PMID 7811158.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 American Psychiatric Association 2000a, p. 349

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association 2000a, p. 412

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Delgado PL and Schillerstrom J (2009). "Cognitive Difficulties Associated With Depression: What Are the Implications for Treatment?". Psychiatric Times 26 (3).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 American Psychiatric Association 2000a, p. 350

- ↑ "Insomnia: Assessment and Management in Primary Care". American Family Physician 59 (11): 3029–38. 1999. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ↑ Patel V, Abas M, Broadhead J (2001). "Depression in developing countries: Lessons from Zimbabwe". BMJ 322 (7284): 482–84. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7284.482.

- ↑ Faculty of Psychiatry of Old Age, NSW Branch, RANZCP; Kitching D Raphael B (2001). Consensus Guidelines for Assessment and Management of Depression in the Elderly (PDF). North Sydney, New South Wales: NSW Health Department. p. 2. ISBN 0-7347-3341-0.

- ↑ Yohannes AM and Baldwin RC (2008). "Medical Comorbidities in Late-Life Depression". Psychiatric Times 25 (14).

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association 2000a, p. 354

- ↑ Brunsvold GL, Oepen G (2008). "Comorbid Depression in ADHD: Children and Adolescents". Psychiatric Times 25 (10).

- ↑ Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Liu J, Swartz M, Blazer DG (1996). "Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: results from the US National Comorbidity Survey". British Journal of Psychiatry 168 (suppl 30): 17–30. PMID 8864145.

- ↑ Hirschfeld RM (2001). "The Comorbidity of Major Depression and Anxiety Disorders: Recognition and Management in Primary Care". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 3 (6): 244–254. PMC 181193. PMID 15014592.

- ↑ Sapolsky Robert M (2004). Why zebras don't get ulcers. Henry Holt and Company, LLC. pp. 291–98. ISBN 0-8050-7369-8.

- ↑ Grant BF (1995). "Comorbidity between DSM-IV drug use disorders and major depression: Results of a national survey of adults". Journal of Substance Abuse 7 (4): 481–87. doi:10.1016/0899-3289(95)90017-9. PMID 8838629.

- ↑ Hallowell EM, Ratey JJ (2005). Delivered from distraction: Getting the most out of life with Attention Deficit Disorder. New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 253–55. ISBN 0-345-44231-8.

- ↑ Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K (2003). "Depression and Pain Comorbidity: A Literature Review". Archives of Internal Medicine 163 (20): 2433–45. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. PMID 14609780.

- ↑ Swardfager W, Herrmann N, Marzolini S, Saleem M, Farber SB, Kiss A, Oh PI, Lanctôt KL (2011). "Major depressive disorder predicts completion, adherence, and outcomes in cardiac rehabilitation: a prospective cohort study of 195 patients with coronary artery disease.". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 72 (9): 1181–8. doi:10.4088/jcp.09m05810blu. PMID 21208573.

- ↑ Schulman J and Shapiro BA (2008). "Depression and Cardiovascular Disease: What Is the Correlation?". Psychiatric Times 25 (9).

- ↑ Department of Health and Human Services (1999). "The fundamentals of mental health and mental illness" (PDF). Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, Poulton R (July 2003). "Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene". Science 301 (5631): 386–89. Bibcode:2003Sci...301..386C. doi:10.1126/science.1083968. PMID 12869766.

- ↑ Haeffel GJ, Getchell M, Koposov RA, Yrigollen CM, Deyoung CG, Klinteberg BA, Oreland L, Ruchkin VV, Grigorenko EL (2008). "Association between polymorphisms in the dopamine transporter gene and depression: evidence for a gene-environment interaction in a sample of juvenile detainees" (PDF). Psychol Sci 19 (1): 62–9. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02047.x. PMID 18181793.

- ↑ Slavich GM (2004). "Deconstructing depression: A diathesis-stress perspective (Opinion)". APS Observer. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ↑ Schmahmann JD (2004). "Disorders of the cerebellum: ataxia, dysmetria of thought, and the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome". J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 16 (3): 367–78. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.16.3.367. PMID 15377747.

- ↑ Konarski JZ, McIntyre RS, Grupp LA, Kennedy SH (May 2005). "Is the cerebellum relevant in the circuitry of neuropsychiatric disorders?". J Psychiatry Neurosci 30 (3): 178–86. PMID 15944742.

- ↑ Schmahmann JD, Weilburg JB, Sherman JC (2007). "The neuropsychiatry of the cerebellum – insights from the clinic". Cerebellum 6 (3): 254–67. doi:10.1080/14734220701490995. PMID 17786822.

- ↑ Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL (2006). "A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression". American Journal of Psychiatry 163 (1): 109–14. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.109. PMID 16390897.

- ↑ Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Bergman M, Reich W, Hesselbrock VM, Smith TL (1997). "Comparison of induced and independent major depressive disorders in 2,945 alcoholics". Am J Psychiatry 154 (7): 948–57. doi:10.1176/ajp.154.7.948. PMID 9210745.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Professor Heather Ashton (2002). "Benzodiazepines: How They Work and How to Withdraw".

- ↑ Barlow 2005, p. 226

- ↑ Shah N, Eisner T, Farrell M, Raeder C (July–August 1999). "An overview of SSRIs for the treatment of depression" (PDF). Journal of the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Nutt DJ (2008). "Relationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 69 Suppl E1: 4–7. PMID 18494537.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Krishnan V, Nestler EJ (October 2008). "The molecular neurobiology of depression". Nature 455 (7215): 894–902. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..894K. doi:10.1038/nature07455. PMC 2721780. PMID 18923511.

- ↑ Hirschfeld RM (2000). "History and evolution of the monoamine hypothesis of depression". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 61 Suppl 6: 4–6. PMID 10775017.

- ↑ Lacasse JR, Leo J (2005). "Serotonin and depression: A disconnect between the advertisements and the scientific literature". PLoS Med 2 (12): e392. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020392. PMC 1277931. PMID 16268734. Retrieved 30 October 2008. Lay summary – Medscape (8 November 2005).

- ↑ Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, Liang KY, Eaves L, Hoh J, Griem A, Kovacs M, Ott J, Merikangas KR (June 2009). "Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis". JAMA 301 (23): 2462–71. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.878. PMC 2938776. PMID 19531786.

- ↑ Munafò MR, Durrant C, Lewis G, Flint J (February 2009). "Gene X environment interactions at the serotonin transporter locus". Biol. Psychiatry 65 (3): 211–9. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.009. PMID 18691701.

- ↑ Uher R, McGuffin P (January 2010). "The moderation by the serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the etiology of depression: 2009 update". Mol. Psychiatry 15 (1): 18–22. doi:10.1038/mp.2009.123. PMID 20029411.

- ↑ Kempton MJ, Salvador Z, Munafò MR, Geddes JR, Simmons A, Frangou S, Williams SC (2011). "Structural Neuroimaging Studies in Major Depressive Disorder: Meta-analysis and Comparison With Bipolar Disorder". Arch Gen Psychiatry 68 (7): 675–90. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.60. PMID 21727252. see also MRI database at www.depressiondatabase.org

- ↑ Arnone D, McIntosh AM, Ebmeier KP, Munafò MR, Anderson IM (July 2011). "Magnetic resonance imaging studies in unipolar depression: Systematic review and meta-regression analyses". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 22 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.05.003. PMID 21723712.

- ↑ Herrmann LL, Le Masurier M, Ebmeier KP (2008). "White matter hyperintensities in late life depression: a systematic review". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 79 (6): 619–24. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.124651. PMID 17717021.