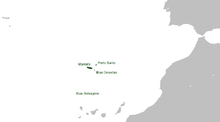

Madeira wine

Madeira is a fortified Portuguese wine made in the Madeira Islands. Madeira is produced in a variety of styles ranging from dry wines which can be consumed on their own as an aperitif, to sweet wines more usually consumed with dessert. Cheaper versions are often flavoured with salt and pepper for use in cooking.

The islands of Madeira have a long winemaking history, dating back to the Age of Exploration when Madeira was a standard port of call for ships heading to the New World or East Indies. To prevent the wine from spoiling, neutral grape spirits were added. On the long sea voyages, the wines would be exposed to excessive heat and movement which transformed the flavour of the wine. This was discovered by the wine producers of Madeira when an unsold shipment of wine returned to the islands after a round trip. Today, Madeira is noted for its unique winemaking process which involves heating the wine up to temperatures as high as 60 °C (140 °F) for an extended period of time and deliberately exposing the wine to some levels of oxidation. Because of this unique process, Madeira is a very robust wine that can be quite long lived even after being opened.[1]

Some wines produced in small quantities in Crimea, California and Texas are also referred to as "Madeira" or "Madera", although those wines do not conform to the EU PDO regulations. In conformance with these EU regulations most countries limit the use of the term Madeira or Madère to only those wines that come from the Madeira Islands.[2]

History

Development and success (15th – 18th centuries)

The roots of Madeira's wine industry date back to the Age of Exploration, when Madeira was a regular port of call for ships travelling to the New World and East Indies. By the 16th century, records indicate that a well-established wine industry on the island supplied these ships with wine for the long voyages across the sea. The earliest examples of Madeira were unfortified and had the habit of spoiling at sea. However, following the example of Port, a small amount of distilled alcohol made from cane sugar was added to stabilize the wine by boosting the alcohol content (the modern process of fortification using brandy did not become widespread till the 18th century). The Dutch East India Company became a regular customer, picking up large (112 gal/423 l) casks of wine known as "pipes" for their voyages to India.

The intense heat and constant movement of the ships had a transforming effect on the wine, as discovered by Madeira producers when one shipment was returned to the island after a long trip. The customer was found to prefer the taste of this style of wine, and Madeira labeled as vinho da roda (wines that have made a round trip) became very popular. Madeira producers found that aging the wine on long sea voyages was very costly, so began to develop methods on the island to produce the same aged and heated style. They began storing the wines on trestles at the winery or in special rooms known as estufas, where the heat of island sun would age the wine.[3]

The 18th century was the "golden age" for Madeira. The wine's popularity extended from the American colonies and Brazil in the New World to Great Britain, Russia, and Northern Africa. The American colonies, in particular, were enthusiastic customers, consuming as much as a quarter of all wine produced on the island each year.

Early American history (17th – 18th centuries)

Madeira was an important wine in the history of the United States of America. No wine-quality grapes could be grown among the 13 colonies, so imports were needed, with a great focus on Madeira.[3][4] One of the major events on the road to revolution in which Madeira played a key role was the British seizure of John Hancock’s sloop the Liberty on May 9, 1768. Hancock's boat was seized after he had unloaded a cargo of 25 pipes (3,150 gallons) of Madeira, and a dispute arose over import duties. The seizure of the Liberty caused riots to erupt among the people of Boston.[5][6]

Madeira was a favorite of Thomas Jefferson, and it was used to toast the Declaration of Independence.[3] George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams are also said to have appreciated the qualities of Madeira. The wine was mentioned in Benjamin Franklin's autobiography. On one occasion, Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail, of the great quantities of Madeira he consumed while a Massachusetts delegate to the Continental Congress. A bottle of Madeira was used by visiting Captain James Server to christen USS Constitution in 1797. Chief Justice John Marshall was also known to appreciate Madeira, as well as his cohorts on the early U.S. Supreme Court.

Modern era (19th century – present)

The mid-19th century ushered an end to the industry's prosperity. First came the 1851 discovery of powdery mildew, which severely reduced production over the next three years. Just as the industry was recovering through the use of the copper-based Bordeaux mixture fungicide, the phylloxera epidemic that had plagued France and other European wine regions reached the island. By the end of the 19th century, most of the island's vineyards had been uprooted, and many were converted to sugar cane production. The majority of the vineyards that did replant chose to use American vine varieties, such as Vitis labrusca, Vitis riparia and Vitis rupestris or hybrid grape varieties rather than replant with the Vitis vinifera varieties that were previously grown.

By the turn of the 20th century, sales started to slowly return to normal, until the industry was rocked again by the Russian Revolution and American Prohibition, which closed off two of Madeira's biggest markets.[3] The rest of the 20th century saw a downturn for Madeira, both in sales and reputation, as low quality "cooking wine" became primarily associated with the island—much as it had for Marsala.

But towards the end of 20th century, some producers started a renewed focus on quality—ripping out the hybrid and American vines and replanting with the "noble grape" varieties of Sercial, Verdelho, Bual and Malvasia. The "workhorse" varieties of Tinta Negra Mole and Complexa are still present and in high use, but hybrid grapes were officially banned from wine production in 1979. Today, Madeira's primary markets are in the Benelux countries, France, and Germany; emerging markets are growing in Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[3]

Viticulture

Climate and geography

The island of Madeira has an oceanic climate with some tropical influences. With high rainfall and average mean temperature of 66 °F (19 °C), the threats of fungal grape diseases and botrytis rot are constant viticultural hazards. To combat these threats, Madeira vineyards are often planted low trellises, known as latada, that raise the canopy of the vine off the ground similar to a style used in the Vinho Verde region of Portugal. The terrain of the mountainous volcanic island is difficult to cultivate, so vineyards are planted on man-made terraces of red and basaltic bedrock. These terraces, known as poios, are very similar to the terraces of the Douro that make Port wine production possible. The use of mechanical harvesting and vineyard equipment is near impossible, making wine grape growing a costly endeavor on the island.[3] Many vineyards have in the past been ripped up for commercial tourist developments or replanted with such products as bananas for commercial concerns. Some replanting is taking place on the island; however, the tourist trade is generally seen as a more lucrative business than wine-making.[1]

Grape varieties

The four major grape varieties used for Madeira production are (from sweetest to driest) Malvasia, Bual, Verdelho and Sercial. These varieties also lend their names to Madeira labeling, as discussed below. Occasionally one sees Terrantez, Bastardo and Moscatel varieties, although these are now increasingly rare on the island because of oidium and phylloxera. After the phylloxera epidemic, many wines were "mislabeled" as containing one of these noble grape varieties, which were reinterpreted as "wine styles" rather than true varietal names. Since the epidemic, Tinta Negra or Negra Mole and Complexa are the workhorse varieties on the island, and are found in various concentrations in many blends and vintage wines. Of these, Bastardo and Tinta Negra are red grape varieties, but the rest are all white.[1]

Regulations enacted recently by the European Union have applied the rule that 85% of the grapes in the wine must be of the variety on the label. Thus, wines from before the late 19th century (pre-phylloxera) and after the late 20th century conform to this rule. Other "varietally labelled" madeiras, from most of the 20th century, do not. Modern Madeiras which do not carry a varietal label are generally made from Tinta Negra Mole.[1]

Other varieties planted on the island, though not legally permitted for Madeira production, include Arnsburger, Cabernet Sauvignon, and the American hybrids Cunningham and Jacquet.[3]

Winemaking

The initial winemaking steps of Madeira start out like most other wines: grapes are harvested, crushed, pressed, and then fermented in either stainless steel or oak casks. The grape varieties destined for sweeter wines – Bual and Malvasia – are often fermented on their skins to leach more phenols from the grapes to balance the sweetness of the wine. The more dry wines – made from Sercial, Verdelho, and Tinta Negra Mole – are separated from their skins prior to fermentation. Depending on the level of sweetness desired, fermentation of the wine is halted at some point by the addition of neutral grape spirits. Producers of cheaper Madeira will usually ferment the wine completely dry, regardless of grape variety, and then fortify the wine so as not to lose any alcohol to evaporation during the estufagem aging (see below).

The wines undergo the estufagem aging process to produce Madeira's distinctive flavor.

The wines may then be artificially sweetened and colored. Colourings such as caramel coloring have been used in the past to give some consistency (see also whiskey), although this practice is decreasing.[3]

"Estufagem" process

What makes Madeira wine production unique is the estufagem aging process, meant to duplicate the effect of a long sea voyage on the aging barrels through tropical climates. Three main methods are used to heat age the wine, used according to the quality and cost of the finished wine:

- Cuba de Calor: The most common, used for low cost Madeira, is bulk aging in low stainless steel or concrete tanks surrounded by either heat coils or piping that allow hot water to circulate around the container. The wine is heated to temperatures as high as 130 °F (55 °C) for a minimum of 90 days as regulated by the Madeira Wine Institute.

- Armazém de Calor: Only used by the Madeira Wine Company, this method involves storing the wine in large wooden casks in a specially designed room outfitted with steam-producing tanks or pipes that heat the room, creating a type of sauna. This process more gently exposes the wine to heat, and can last from six months to over a year.

- Canteiro: Used for the highest quality Madeiras, these wines are aged without the use of any artificial heat, being stored by the winery in warm rooms left to age by the heat of the sun. In cases such as vintage Madeira, this heating process can last from 20 years to 100 years.[3]

Much of the characteristic flavour of Madeira is due to this practice, which hastens the mellowing of the wine and also tends to check secondary fermentation in as much as it is, in effect, a mild kind of pasteurization. Furthermore, the wine is deliberately exposed to air, causing it to oxidize. The resulting wine has a colour similar to a tawny port wine. Wine tasters sometimes describe a wine which has been exposed to excessive heat during its storage as being cooked or maderized.

Styles

The noble varieties

The four major styles of Madeira are named according to the grape variety used. Ranging from the driest style to the sweetest style, the Mereira types are:

- Sercial is nearly fermented completely dry, with very little residual sugar (0.5 to 1.5° on the Baumé scale). This style of wine is characterised with high-toned colours, almond flavours, and high acidity.

- Verdelho has its fermentation halted a little earlier than Sercial, when its sugars are between 1.5 and 2.5° Baumé. This style of wine is characterized by smokey notes and high acidity.

- Bual (also called Boal) has its fermentation halted when its sugars are between 2.5 to 3.5° Baumé. This style of wine is characterized by its dark colour, medium-rich texture, and raisin flavours.

- Malvasia (also known as Malmsey or Malvazia) has its fermentation halted when its sugars are between 3.5 and 6.5° Baumé. This style of wine is characterised by its dark colour, rich texture, and coffee-caramel flavours. Like other Madeiras made from the noble grape varieties, the Malvasia grape used in Malmsey production has naturally high levels of acidity in the wine, which balances with the high sugar levels so the wines do not taste cloyingly sweet.

Other labeling

Wines made from at least 85% of the noble varieties of Sercial, Verdelho, Bual, and Malmsey are usually labeled based on the amount of time they were aged:[1]

- Reserve (five years) – This is the minimum amount of aging a wine labeled with one of the noble varieties is permitted to have.

- Special Reserve (10 years) – At this point, the wines are often aged naturally without any artificial heat source.

- Extra Reserve (over 15 years) – This style is rare to produce, with many producers extending the aging to 20 years for a vintage or producing a colheita. It is richer in style than a Special Reserve Madeira.

- Colheita or Harvest – This style includes wines from a single vintage, but aged for a shorter period than true Vintage Madeira. The wine can be labeled with a vintage date, but includes the word colheita on it.

- Vintage or Frasqueira – This style must be aged at least 20 years.

A wine labeled as Finest has been aged for at least three years. This style is usually reserved for cooking.

The terms pale, dark, full and rich can also be included to describe the wine's colour.

Since 1993, Madeira produced from Tinta Negra Mole grapes is legally restricted to use generic terms on the label to indicate the level of sweetness as seco (dry), meio seco (medium dry), meio doce (medium sweet) and doce (sweet).

Wines listed with Solera were made in a style similar to sherry, with fractional blending of wines from different vintages in a solera system.[3]

Rainwater

A style called "Rainwater" is rarely produced today, and when it is, it is usually shipped only to the United States. This style of wine is mild and similar to Verdelho, but can be expected to be made from Tinta Negra Mole, and is primarily used as an apéritif.

Accounts conflict as to how this style was developed. The most common is the name derives from the vineyards on the steep hillsides, where irrigation was difficult, and the vines were dependent on the local rain water for survival. Another theory involves a shipment destined for the American colonies that was accidentally diluted by rainwater while it sat on the docks in Savannah, Georgia. Rather than dump the wines, the merchants tried to pass it off as a "new style" of Madeira and were surprised at its popularity among the Americans.[1]

Characteristics

Exposure to extreme temperature and oxygen accounts for Madeira's stability; an opened bottle will survive unharmed for a considerable time, up to a year. Properly sealed in bottles, it is one of the longest-lasting wines; Madeiras have been known to survive over 150 years in excellent condition. It is not uncommon to see 100-year-old Madeiras for sale at stores that specialize in rare wine. Vintages dating back to 1780 are known to exist. The oldest bottle that has come onto the market is a 1715 Terrantez.[7]

Before the advent of artificial refrigeration, Madeira wine was particularly prized in areas where it was impractical to construct wine cellars (as in parts of the southern United States) because, unlike many other fine wines, it could survive being stored over hot summers without significant damage.

Uses

Most Madeira is consumed as wine. Popular uses include apéritifs (pre-meal) and digestifs (post-meal).[8] In Britain it has traditionally been associated with Madeira cake.[9]

Madeira is also used as a flavor agent in cooking. Lower-quality Madeira wines may be flavored with salt and pepper to prevent their sale as Madeira wine, and then exported for cooking purposes.[10] Madeira wine is commonly used in tournedos Rossini and sauce madère (Madeira sauce).[11] Unflavored Madeira may also be used in cooking, such as the dessert dish "Plum in madeira".

See also

- Have Some Madeira M'Dear

- List of Portuguese wine regions

- Terras Madeirenses VR, a Vinho Regional designation for simpler, non-fortified wines from Madeira

- History of Portuguese wine

- Port wine

- Sherry

- Marsala wine

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Stevenson, T. (2005), The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia, Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 0-7566-1324-8. Pages 340-341.

- ↑ "Labelling of wine and certain other wine sector products". Europa: Summaries of EU legislation. 20 August 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Robinson, J., ed. (2006), The Oxford Companion to Wine (Third ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-860990-6. Pages 416-419.

- ↑ Robinson, J., ed. (2006), The Oxford Companion to Wine (Third ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-860990-6. Pages 719-720.

- ↑ encarta.msn.com. "John Hancock". Encarta Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2009-11-01. Retrieved on Feb. 23, 2007

- ↑ ushistory.org. "John Hancock".

- ↑ McCoy, Elin (2010-03-29). "J.P. Morgan's Favored Madeira Wines Make Comeback: Elin McCoy". Bloomberg.

- ↑ Herbst, Sharon Tyler; Herbst, Ron (2007, 2001, 1995, 1990), The Food Lover's Companion (Fourth ed.), Barron's Educational Series, Inc. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ The essential baking cookbook, Murdoch Books Pty Limited, Murdoch Books, 2005,ISBN 1-74045-542-8, ISBN 978-1-74045-542-8, page 59

- ↑ "Vinhos Justino Henriques, Filhos, Lda. = VJH". Madeira Wine Guide. 6 January 2007.

- ↑ Sokolov, Raymond A. (1976), The Saucier's Apprentice: A Modern Guide to Classic French Sauces for the Home, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., ISBN 978-0-307-76480-5

Further reading

- Liddell, Alex (1998). Madeira. Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-19096-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Madeira wine. |

- Madeira Wine Guide by Dr. Wolf Peter Reutter

- Images related to Madeira wine

- Madeira Wine History

- 'The Wine-Dark Sea', review of David Hancock's Oceans of Wine: Madeira and the Emergence of American Trade and Taste in the Oxonian Review of Books

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||