Macedonian alphabet

| Macedonian Alphabet | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Languages | Macedonian |

Time period | 1944–present |

Parent systems |

Cyrillic script

|

| ISO 15924 |

Cyrl, 220 |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

Unicode alias | Cyrillic |

Unicode range | subset of Cyrillic (U+0400...U+04F0) |

The orthography of Macedonian includes an alphabet (Macedonian: Македонска азбука, Makedonska azbuka), which is an adaptation of the Cyrillic script, as well as language-specific conventions of spelling and punctuation.

The Macedonian alphabet was standardized in 1944 by a committee formed in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia (then part of the federation of Yugoslavia) after the liberation from the Nazis in World War II. The alphabet used the same phonemic principles employed by Vuk Karadžić (1787-1864) and Krste Misirkov (1874-1926).

Before standardization, the language had been written in a variety of different versions of Cyrillic by different writers, influenced by Bulgarian, Early Cyrillic or Serbian orthography.

The alphabet

Origins:

- Phoenician alphabet

- Greek alphabet

- Latin alphabet

- Cyrillic script

- Macedonian Cyrillic alphabet

- Greek alphabet

The following table provides the upper and lower case forms of the Macedonian alphabet, along with the IPA value for each letter:

| Letter IPA Name |

А а /a/ /a/ |

Б б /b/ /bə/ |

В в /v/ /və/ |

Г г /ɡ/ /ɡə/ |

Д д /d/ /də/ |

Ѓ ѓ /ɟ/ /ɟə/ |

Е е /ɛ/ /ɛ/ |

Ж ж /ʒ/ /ʒə/ |

З з /z/ /zə/ |

Ѕ ѕ /d͡z/ /d͡zə/ |

И и /i/ /i/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letter IPA Name |

Ј ј /j/ /jə/ |

К к /k/ /kə/ |

Л л /ɫ/ ([ɫ], [l]) /ɫə/ |

Љ љ /l/ /lə/ |

М м /m/ /mə/ |

Н н /n/ /nə/ |

Њ њ /ɲ/ /ɲə/ |

О о /ɔ/ /ɔ/ |

П п /p/ /pə/ |

Р р /r/ /rə/ |

С с /s/ /sə/ |

| Letter IPA Name |

Т т /t/ /tə/ |

Ќ ќ /c/ /cə/ |

У у /u/ /u/ |

Ф ф /f/ /fə/ |

Х х /x/ /xə/ |

Ц ц /t͡s/ /t͡sə/ |

Ч ч /t͡ʃ/ /t͡ʃə/ |

Џ џ /d͡ʒ/ /d͡ʒə/ |

Ш ш /ʃ/ /ʃə/ |

In addition to the standard sounds of the letters Ѓ and Ќ above, in some accents these letters represent /dʑ/ and /tɕ/, respectively.

Cursive alphabet

The above table contains the printed form of the Macedonian alphabet; the cursive script is significantly different, and is illustrated below in lower and upper case (letter order and layout below corresponds to table above).

Specialized letters

Macedonian has a number of phonemes not found in neighbouring languages. The committees charged with drafting the Macedonian alphabet decided on phonemic principle with a one-to-one match between letters and distinctive sounds.

Unique letters

| South Slavic languages and dialects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Western South Slavic

|

||||||

|

Eastern South Slavic |

||||||

|

Transitional dialects

|

||||||

|

Alphabets

|

||||||

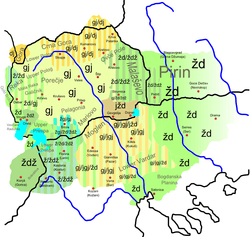

Ѓ and Ќ

In "On Macedonian Matters", Misirkov used the combinations Г' and К' to represent the phonemes /ɟ/ and /c/, which are unique to Macedonian among South Slavic languages. In his magazine "Vardar", Misirkov used the letters Ѓ and Ќ, as did Dimitar Mirčev in his book. Eventually, Ѓ and Ќ were adopted for the Macedonian alphabet.

In 1887, Temko Popov of the Secret Macedonian Committee used the digraphs гј and кј in his article "Who is guilty?". The following year, the committee published the "Macedonian primer" (written by Kosta Grupče and Naum Evro) which used the Serbian letters Ђ and Ћ for these phonemes.

Marko Cepenkov, Gjorgjija Pulevski and Parteniy Zografski used ГЬ and КЬ.

Despite their forms, Ѓ and Ќ are ordered not after Г and К, but after Д and Т respectively, based on phonetic similarity. This corresponds to the alphabet positions of Serbian Ђ and Ћ respectively. These letters often correspond to Macedonian Ѓ and Ќ in cognates (for example, Macedonian "шеќер" (šeḱer, sugar) is analogous to Serbian/Croatian "шећер/šećer"), but they are phonetically different.

Ѕ

The Cyrillic letter Dze (S s), representing the sound /d͡z/, is based on Dzělo, the eighth letter of the early Cyrillic alphabet. Although a homoglyph to the Latin letter S, the two letters are not directly related. Both the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet and the Russian alphabet also had a letter Ѕ, although Romanian Cyrillic was replaced with a Latin alphabet in the 1860s, and the letter Ѕ was abolished in Russian in the early 18th century.

It should be noted that while Ѕ is generally transcribed as dz, it is a distinct phoneme and is not analogous to ДЗ, which is also used in Macedonian orthography for /d.z/. Ѕ is sometimes described as soft-dz.

Dimitar Mirčev was most likely the first writer to use this letter in print prior to the standardization of 1944.

Letters analogous to Serbian Cyrillic

Ј

Prior to standardization, the IPA phoneme /j/ (represented by Ј in the modern Macedonian alphabet) was represented variously as:

- Й/й (by Gjorgjija Pulevski in "Macedonian fairy");

- І/і (by Misirkov in On Macedonian Matters, Marko Cepenkov, Dimitar Mirčev, in four of Gjorgjija Pulevski's works, in the "Macedonian primer" by the Secret Macedonian Committee and by members of the "Vinegrover" movement); or

- Ј/ј (by Gjorgjija Pulevski in his "Dictionary of four languages" and "Dictionary of three languages", and by Temko Popov in his article "Who is guilty?")

Eventually the Ј was selected to represent /j/.

Љ and Њ

The letters Љ and Њ (/l/ and /ɲ/) are ultimately from the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet. Historically, Macedonian writers have also used:

- the digraphs ЛЬ and НЬ (used by Gjorgjija Pulevski and in the "Macedonian primer" of the Secret Macedonian Committee)

- the digraphs ЛЈ and НЈ (used by Temko Popov)

- the combinations Л' and Н' (used by Krste Misirkov and Dimitar Mirčev)

Џ

The letter Џ (representing the phoneme /dʒ/) was likely adopted from the Serbian alphabet and used by Gjorgjija Pulevski in four of his works, as well as by the Secret Macedonian Committee and Dimitar Mirčev. Misirkov used the digraph ДЖ. The letter Џ is used today.

Accented letters

The accented letters Ѐ and Ѝ are not regarded as separate letters, nor are they accented letters (as in French, for example). Rather, they are the standard letters Е and И topped with an accent when they stand in words that have homographs, so as to differentiate between them (for example, "сè се фаќа" – se se fakja, "all may be touched").

Development of the Macedonian alphabet

Until the modern era, Macedonian was predominantly a spoken language, with no standardized written form of the vernacular dialects. Formal written communication was usually in the Church Slavonic language[1] (in Pirin and Vardar Macedonia) or in Greek (in Greek Macedonia),[1] which were the languages of liturgy, and were therefore considered the 'formal languages'.[2]

The decline of the Ottoman Empire from the mid-19th century coincided with Slavic resistance to the use of Greek in Orthodox churches and schools,[3] and a resistance amongst some Macedonians to the introduction of standard Bulgarian in Vardar Macedonia.[4] During the period of Bulgarian National Revival many Christians from Macedonia supported the struggle for creation of Bulgarian cultural, educational and religious institutions, including Bulgarian schools that used the version of Cyrillic adopted by other Bulgarians. The majority of the intellectual and political leaders of the Macedonian Bulgarians used this version of the Cyrillic script, which was also changed in the 19th and early 20th century.[5] At the end of 1879 Despot Badžović published the 'Alphabet Book for Serbo-Macedonian Primary Schools' (Serbian: Буквар за србо-македонске основне школе) written on "Serbo-Macedonian dialect".[6]

The latter half of the 19th century saw increasing literacy and political activity amongst speakers of Macedonian dialects, and an increasing number of documents were written in the dialects. At the time, transcriptions of Macedonian used Cyrillic with adaptations drawing from Old Church Slavonic, Serbian and Bulgarian, depending on the preference of the writer.

Early attempts to formalize written Macedonian included Krste Misirkov's book "On Macedonian Matters" (1903). Misirkov used the Cyrillic script with several adaptations for Macedonian:

- i (where Ј is used today);

- л' (where Љ is used today);

- н' (where Њ is used today);

- г' (where Ѓ is used today);

- к' (where Ќ is used today); and

- ѕ (as used today).

Another example is from Bulgarian folklorist from Macedonia Marko Cepenkov who published in two issues of the "A Collection of folklore, science and literature" (1892, 1897) folklore materials from Macedonia.[7] Cepenkov used a version of Bulgarian Cyrillic alphabet with his own adaptations for some of the local Macedonian dialects. He did not use ѣ, using е instead, and did not use the ъ in the final position of masculine nouns. Other adaptations included:

- і (where Ј is used today);

- щ (where Шт is used today);

- ль (where Љ is used today);

- нь (where Њ is used today);

- гь (where Ѓ is used today);

- кь (where Ќ is used today);

- дж (where Џ is used today);

- ѫ (sometimes for А).

Between the expulsion of the Ottoman Empire from Macedonia in the Balkan Wars of 1912/13, and the liberation of Vardar Macedonia from the Nazis in 1944, Northern Macedonia was divided between Serbia (within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) and Bulgaria, and standard Serbian and Bulgarian were the official languages. The Serbian and Bulgarian authorities considered Macedonian to be a dialect of Serbian or Bulgarian respectively, and according to some authors proscribed its use[8][9][10][11] (see also History of the Macedonian language). However, in Bulgaria have issued books in Macedonian dialects[12][13] and in 1920s and 1930s in Yugoslavia were published some texts in Macedonian dialects, too.[14][15][16] Greek was used in areas under Greek control.

Standardization of the Macedonian Alphabet

With the liberation of Vardar Macedonia from German–Bulgarian occupation 1944 and the incorporation of the territory into the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia as the Socialist Republic of Macedonia, the Yugoslav authorities recognized a distinct Macedonian ethnic identity and language. The Anti-Fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM, effectively the Macedonian provisional government) formed a committee to standardize the literary Macedonian language and alphabet.

ASNOM rejected the first committee's recommendations, and formed a second committee, whose recommendations were accepted. The (second) committees' recommendations were strongly influenced by the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet (28 of the Macedonian alphabet's 31 letters are common to both Macedonian and Serbian, the letters unique to Macedonian being Ѓ, Ѕ, and Ќ), and by the works of Krste Misirkov.

The First Committee

The first committee met from November 27, 1944 to December 4, 1944, and was composed of prominent Macedonian academics and writers (see list below). The committee chose the dialects of Veles, Prilep and Bitola as the basis for the literary language (as Misirkov had in 1903), and proposed a Cyrillic alphabet. The first committee's recommendation was for the alphabet to use

- the Serbian Ј and Џ;

- the Old Church Slavonic Ѕ;

- the Old Church Slavonic Ъ (schwa); and

- Venko Markovski's versions of Љ, Њ, Ќ and Ѓ (which contained a small circle in the bottom-right of Л, Н and К, and a small circle in the top-right of Г).[17]

ASNOM rejected the first committee's recommendations, and convened a second committee. Although no official reason was provided, several reasons are supposed for the rejection of the first committee's recommendation, including internal disagreement over the inclusion of Ъ (the Big Yer, as used in Bulgarian), and the view that its inclusion made the alphabet "too close" to the Bulgarian alphabet.

While some Macedonian dialects contain a clear phonemic schwa and used a Bulgarian-style Ъ, according to some opinions the western dialects – on which the literary language is based – do not. Blaže Koneski objected to the inclusion of the Big Yer on the basis that since there was no Big Yer in the literary language (not yet standardized), there was no need for it to be represented in the alphabet. By excluding it from the alphabet, speakers of schwa-dialects would more rapidly adapt to the standard dialect.[18] On the other hand, opponents of Koneski indicatеd that this phoneme is distributed among the western Macedonian dialects too and a letter Ъ should be included in the standardized at that time literary language.[19]

The Second Committee and adoption

With the rejection of the first committee's draft alphabet, ASNOM convened a new committee with five members from the first committee and five new members. On May 3, 1945, the second committee presented its recommendations, which were accepted by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia that same day, and published in Nova Makedonija, the official newspaper.

The committee's recommendations were:

- acceptance of Serbian Ј and Џ;

- acceptance of Old Church Slavonic Ѕ;

- adoption of Serbian Љ and Њ, which were similar in appearance to Markovski's proposed letters;

- creation and adoption of Ќ and Ѓ (over Markovski's proposed letter forms); and

- rejection of Old Church Slavonic Ъ (Big Yer).

The rejection of the Ъ (Big Yer), together with the adoption of four Serbian Cyrillic letters (Ј, Џ, Љ and Њ), led to accusations that the committee was "Serbianizing" Macedonian, while those in favor of including the Big Yer (Ъ) were accused of "Bulgarianizing" Macedonian. Irrespective, the new alphabet was officially adopted in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia on May 16, 1945, and is still used in the Republic of Macedonia and among Macedonian communities around the world.

Committee members

| First Committee | Second Committee |

| m denotes military appointee c denotes civilian appointee * denotes member also served on the second committee |

* denotes member also served on the first committee |

| Epaminonda Popandonov (m) | Vasil Iljoski* |

| Jovan Kostovski (c) | Blaže Koneski* |

| Milka Balvanlieva (m) | Venko Markovski* |

| Dare Džambaz (m) | Mirko Pavlovski* |

| Vasil Iljoski* (c) | Krum Tošev* |

| Georgi Kiselinov (c) | Kiro Hadži-Vasilev |

| Blaže Koneski* (m) | Vlado Maleski |

| Venko Markovski* (m) | Ilija Topalovski |

| Mirko Pavlovski* (c) | Gustav Vlahov |

| Mihail Petruševski (c) | Ivan Mazov |

| Risto Prodanov (m) | |

| Georgi Šoptrajanov (m) | |

| Krum Tošev* (m) | |

| Hristo Zografov (c) | |

| Source: Victor A Friedman[20] | |

See also

- Macedonian braille

- Transliteration of Macedonian

- Serbian Cyrillic alphabet

- Cyrillic script

- Scientific transliteration of Slavic languages

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Macedonian Language in the Balkan Language Environment

- ↑ Prior to the autocephaly of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church in 1872, Old Church Slavonic and Greek were the liturgical languages of Orthodox Christians in Macedonia, and therefore had higher status than the local dialects (see diglossia).

- ↑ "The first philological conference of the Macedonian alphabet and Macedonian literary language: Its precedents and consequences", Victor A. Friedman (1993), pages 162

- ↑ "The first philological conference of the Macedonian alphabet and Macedonian literary language: Its precedents and consequences", Victor A. Friedman (1993), pages 162-3

- ↑ Михайлов, Иван. Как пишеха нашите народни будители и герои

- ↑ Zbornik Matice srpske za istoriju. Матица. 1992. p. 55. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ "A Collection of folklore, science and literature", Book VIII (1892), Book XIV (1897), issue of the Ministry of Public Education, Sofia, in the form of text and .jpg photocopies (Bulgarian)

- ↑ "Language Policy and Language Behavior in Macedonia: Background and Current Events", Victor A Friedman, in "Language Contact – Language Conflict", edited Eran Fraenkel and Christina Kramer, Balkan Studies, Vol 1., p76.

- ↑ "The Sociolinguistics of literary Macedonian", Victor A Friedman, in the International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 1985, Vol. 52, p49.

- ↑ "The first philological conference for the establishment of the Macedonian alphabet and Macedonian literary language: Its precedents and consequences", Victor A Friedman, in "The Earliest Stages of Language Planning", edited by Joshua A Fishman, 1993, p163.

- ↑ "Language Planning in Macedonia and Kosovo", Victor A Friedman, in "Language in the Former Yugoslav Lands", edited by Ranko Bugarski and Celia Hawkesworth (2004), p201.

- ↑ Марковски, Венко. Огинот, Стихотворения, София 1938, 39 с. (, ), Марковски, Венко, Луня. Македонска лирика, София 1940, 160 с. (, ), Марковски, В., Илинден, София 1940, 16 с., Марковски, В., Лулкина песна, София 1939, 40 с.

- ↑ Друговац, Миодраг. Историја на македонската книжевност, Скопје 1990, с. 194.

- ↑ Друговац, Миодраг. Историја на македонската книжевност, Скопје 1990, с. 92.

- ↑ Иванов, Костадин. Ролята на списание "Луч" в национално-освободителната борба на българите във Вардарска Македония, Македонски преглед, бр.2, 2008, с. 25-51.

- ↑ Рацин, Кочо, Бели мугри, Загреб, 1939

- ↑ "The first philological conference of the Macedonian alphabet and Macedonian literary language: Its precedents and consequences", Victor A. Friedman (1993), p169.

- ↑ "The first philological conference of the Macedonian alphabet and Macedonian literary language: Its precedents and consequences", Victor A. Friedman (1993), p171.

- ↑ Кочев, Иван и Иван Александров. Документи по съчиняването на т.нар. македонски книжовен език, София 1993. Regarding the distribution of phoneme schwa in the western Macedonian dialects see Stoykov, Stoyko. Bulgarian dialectology, Sofia 2002, p. 177-179 (Bulgarian)

- ↑ "The first philological conference of the Macedonian alphabet and Macedonian literary language: Its precedents and consequences", Victor A. Friedman (1993), pages 166, 170.

References

- Стојан Киселиновски "Кодификација на македонскиот литературен јазик", Дневник, 1339, сабота, 18 март 2006. (Macedonian)

External links

| ||||||||||||||||