MOX fuel

Mixed oxide fuel, commonly referred to as MOX fuel, is nuclear fuel that contains more than one oxide of fissile material, usually consisting of plutonium blended with natural uranium, reprocessed uranium, or depleted uranium. MOX fuel is an alternative to the low-enriched uranium (LEU) fuel used in the light water reactors that predominate nuclear power generation. For example, a mixture of 7% plutonium and 93% natural uranium reacts similarly, although not identically, to LEU fuel. MOX usually consists of two phases, UO2 and PuO2, and/or a single phase solid solution (U,Pu)O2. The content of PuO2 may vary from 1.5 wt.% to 25–30 wt.% depending on the type of nuclear reactor. Although MOX fuel can be used in thermal reactors to provide energy, efficient fission of plutonium in MOX can only be achieved in fast reactors.[1]

One attraction of MOX fuel is that it is a way of utilizing surplus weapons-grade plutonium, an alternative to storage of surplus plutonium, which would need to be secured against the risk of theft for use in nuclear weapons.[2][3] On the other hand, some studies warned that normalising the global commercial use of MOX fuel and the associated expansion of nuclear reprocessing will increase, rather than reduce, the risk of nuclear proliferation, by encouraging increased separation of plutonium from spent fuel in the civil nuclear fuel cycle.[4][5][6]

Overview

In every uranium-based nuclear reactor core there is both fission of uranium isotopes such as uranium-235 (235

92U), and the formation of new, heavier isotopes due to neutron capture, primarily by uranium-238 (238

92U). Most of the fuel mass in a reactor is 238

92U. By neutron capture and two successive beta decays, 238

92U becomes plutonium-239 (239

94Pu), which, by successive neutron capture, becomes plutonium-240 (240

94Pu), plutonium-241 (241

94Pu), plutonium-242 (242

94Pu) and (after further beta decays) other transuranic or actinide nuclides. 239

94Pu and 241

94Pu are fissile, like 235

92U. Small quantities of uranium-236 (236

92U), neptunium-237 (237

93Np) and plutonium-238 (238

94Pu) are formed similarly from 235

92U.

Normally, with the fuel being changed every three years or so, most of the 239

94Pu is "burned" in the reactor. It behaves like 235

92U, with a slightly higher cross section for fission, and its fission releases a similar amount of energy. Typically about one percent of the spent fuel discharged from a reactor is plutonium, and some two thirds of the plutonium is 239

94Pu. Worldwide, almost 100 tonnes of plutonium in spent fuel arises each year. A single recycling of plutonium increases the energy derived from the original uranium by some 12%, and if the 235

92U is also recycled by re-enrichment, this becomes about 20%.[7] With additional recycling the percentage of fissile (usually meaning odd-neutron number) nuclides in the mix decreases and even-neutron number, neutron-absorbing nuclides increase, requiring the total plutonium and/or enriched uranium percentage to be increased. Today in thermal reactors plutonium is only recycled once as MOX fuel; spent MOX fuel, with a high proportion of minor actinides and even plutonium isotopes, is stored as waste.

Existing nuclear reactors must be re-licensed before MOX fuel can be introduced because using it changes the operating characteristics of a reactor, and the plant must be designed or adapted slightly to take it; for example, more control rods are needed. Often only a third to half of the fuel load is switched to MOX, but for more than 50% MOX loading, significant changes are necessary and a reactor needs to be designed accordingly. The Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station near Phoenix, Arizona was designed for 100% MOX core compatibility but so far have always operated on fresh low enriched uranium. In theory, the three Palo Verde reactors could use the MOX arising from seven conventionally fueled reactors each year and would no longer require fresh uranium fuel.

According to Atomic Energy of Canada Limited (AECL), CANDU reactors could use 100% MOX cores without physical modification.[8][9] AECL reported to the United States National Academy of Sciences committee on plutonium disposition that it has extensive experience in testing the use of MOX fuel containing from 0.5 to 3% plutonium.

The content of un-burnt plutonium in spent MOX fuel from thermal reactors is significant – greater than 50% of the initial plutonium loading. However, during the burning of MOX the ratio of fissile (odd numbered) isotopes to non-fissile (even) drops from around 65% to 20%, depending on burn up. This makes any attempt to recover the fissile isotopes difficult and any bulk Pu recovered would require such a high fraction of Pu in any second generation MOX that it would be impractical. This means that such a spent fuel would be difficult to reprocess for further reuse (burning) of plutonium. Regular reprocessing of biphasic spent MOX is difficult because of the low solubility of PuO2 in nitric acid.[1]

Current applications

Reprocessing of commercial nuclear fuel to make MOX is done in the United Kingdom and France, and to a lesser extent in Russia, India and Japan. China plans to develop fast breeder reactors and reprocessing. Reprocessing of spent commercial-reactor nuclear fuel is not permitted in the United States due to nonproliferation considerations. All of these nations have long had nuclear weapons from military-focused research reactor fuels except Japan.

The United States is building a MOX plant at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina. Although the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and Duke Energy expressed interest in using MOX reactor fuel from the conversion of weapons-grade plutonium,[10] TVA (currently the most likely customer) said in April 2011 that it would delay a decision until it could see how MOX fuel performed in the nuclear accident at Fukushima Daiichi.[11]

Thermal reactors

About 30 thermal reactors in Europe (Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany and France) are using MOX[12] and an additional 20 have been licensed to do so. Most reactors use it as about one third of their core, but some will accept up to 50% MOX assemblies. In France, EDF aims to have all its 900 MWe series of reactors running with at least one-third MOX. Japan aimed to have one third of its reactors using MOX by 2010, and has approved construction of a new reactor with a complete fuel loading of MOX. Of the total nuclear fuel used today, MOX provides 2%.[7]

Licensing and safety issues of using MOX fuel include:[12]

- As plutonium isotopes absorb more neutrons than uranium fuels, reactor control systems may need modification.

- MOX fuel tends to run hotter because of lower thermal conductivity, which may be an issue in some reactor designs.

- Fission gas release in MOX fuel assemblies may limit the maximum burn-up time of MOX fuel.

About 30% of the plutonium originally loaded into MOX fuel is consumed by use in a thermal reactor. If one third of the core fuel load is MOX and two-thirds uranium fuel, there is zero net gain of plutonium in the spent fuel.[12]

All plutonium isotopes are either fissile or fertile, although plutonium-242 needs to absorb 3 neutrons before becoming fissile curium-245; in thermal reactors isotopic degradation limits the plutonium recycle potential. About 1% of spent nuclear fuel from current LWRs is plutonium, with approximate isotopic composition 52% 239

94Pu, 24% 240

94Pu, 15% 241

94Pu, 6% 242

94Pu and 2% 238

94Pu when the fuel is first removed from the reactor.[12]

Fast reactors

Because the fission to capture ratio of neutron cross-section with high energy or fast neutrons changes to favour fission for almost all of the actinides, including 238

92U, fast reactors can use all of them for fuel. All actinides, including TRU or transuranium actinides can undergo neutron induced fission with unmoderated or fast neutrons. A fast reactor is more efficient for using plutonium and higher actinides as fuel. Depending on how the reactor is fueled it can either be used as a plutonium breeder or burner.

These fast reactors are better suited for the transmutation of other actinides than are thermal reactors. Because thermal reactors use slow or moderated neutrons, the actinides that are not fissionable with thermal neutrons tend to absorb the neutrons instead of fissioning. This leads to buildup of heavier actinides and lowers the number of thermal neutrons available to continue the chain reaction.

Fabrication

The first step is separating the plutonium from the remaining uranium (about 96% of the spent fuel) and the fission products with other wastes (together about 3%). This is undertaken at a nuclear reprocessing plant.

Dry mixing

MOX fuel can be made by grinding together uranium oxide (UO2) and plutonium oxide (PuO2) before the mixed oxide is pressed into pellets, but this process has the disadvantage of forming lots of radioactive dust. MOX fuel, consisting of 7% plutonium mixed with depleted uranium, is equivalent to uranium oxide fuel enriched to about 4.5% 235

92U, assuming that the plutonium has about 60–65% 239

94Pu. If weapons-grade plutonium were used (>90% 239

94Pu), only about 5% plutonium would be needed in the mix.

Coprecipitation

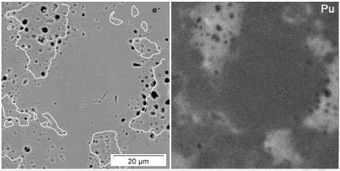

A mixture of uranyl nitrate and plutonium nitrate in nitric acid is converted by treatment with a base such as ammonia to form a mixture of ammonium diuranate and plutonium hydroxide. After heating in a mixture of 5% hydrogen and 95% argon will form a mixture of uranium dioxide and plutonium dioxide. Using a base, the resulting powder can be run through a press and converted into green colored pellets. The green pellet can then be sintered into mixed uranium and plutonium oxide pellet. While this second type of fuel is more homogenous on the microscopic scale (scanning electron microscope) it is possible to see plutonium rich areas and plutonium poor areas. It can be helpful to think of the solid as being like a salami (more than one solid material present in the pellet).

Americium content

Plutonium from reprocessed fuel is usually fabricated into MOX as soon as possible to avoid problems with the decay of short-lived isotopes of plutonium. In particular, 241

94Pu decays to americium-241 (241

95Am), which is a gamma ray emitter, giving rise to a potential occupational health hazard if the separated plutonium over five years old is used in a normal MOX plant. While 241

95Am is a gamma emitter most of the photons it emits are low in energy, so 1 mm of lead, or thick glass on a glovebox will give the operators a great deal of protection to their torsos. When working with large amounts of americium in a glovebox, the potential exists for a high dose of radiation to be delivered to the hands.

As a result old reactor-grade plutonium can be difficult to use in a MOX fuel plant, as the 241

94Pu it contains decays with a short 14.1 year half-life into more radioactive 241

95Am, which makes the fuel difficult to handle in a production plant. Within about 5 years typical reactor-grade plutonium would contain too much 241

95Am (about 3%). But it is possible to purify the plutonium bearing the americium by a chemical separation process. Even under the worst possible conditions the americium/plutonium mixture will never be as radioactive as a spent-fuel dissolution liquor, so it should be relatively straight forward to recover the plutonium by PUREX or another aqueous reprocessing method.

Also, 241

94Pu is fissile while the isotopes of plutonium with even mass numbers are not (in general thermal neutrons will usually fission isotopes with an odd number of neutrons, but rarely those with an even number), so decay of 241

94Pu to 241

95Am leaves plutonium with a lower proportion of isotopes usable as fuel, and a higher proportion of isotopes that simply capture neutrons (though they may become fissile isotopes after one or more captures). The decay of 238

94Pu to 234

92U and subsequent removal of this uranium would have the opposite effect, but 238

94Pu both has a longer halflife (87.7 years vs. 14.3) and is a smaller proportion of the spent nuclear fuel. 239

94Pu, 240

94Pu, and 242

94Pu all have much longer halflives so that decay is negligible. (244

94Pu has an even longer halflife, but is unlikely to be formed by successive neutron capture because 243

94Pu quickly decays with a halflife of 5 hours giving 243

95Am.)

Curium content

It is possible that both americium and curium could be added to a U/Pu MOX fuel before it is loaded into a fast reactor. This is one means of transmutation. Work with curium is much harder than americium because curium is a neutron emitter, the MOX production line would need to be shielded with both lead and water to protect the workers.

Also, the neutron irradiation of curium generates the higher actinides, such as californium, which increase the neutron dose associated with the used nuclear fuel; this has the potential to pollute the fuel cycle with strong neutron emitters. As a result, it is likely that curium will be excluded from most MOX fuels.

Thorium MOX

MOX fuel containing thorium and plutonium oxides is also being tested.[13] According to a Norwegian study, "the coolant void reactivity of the thorium-plutonium fuel is negative for plutonium contents up to 21%, whereas the transition lies at 16% for MOX fuel." The authors concluded, "Thorium-plutonium fuel seems to offer some advantages over MOX fuel with regards to control rod and boron worths, CVR and plutonium consumption."

See also

- Nuclear fuel cycle

- Nuclear breeder reactor

- Spent nuclear fuel shipping cask

- Nuclear power

- Nuclear fission

- Nuclear power plant

- Hanford Site

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Burakov, B. E.; Ojovan, M. I.; Lee, W. E. (2010). Crystalline Materials for Actinide Immobilisation. London: Imperial College Press. p. 198.

- ↑ Military Warheads as a Source of Nuclear Fuel

- ↑ http://fissilematerials.org/blog/2011/04/us_mox_program_wanted_rel.html

- ↑ Is U.S. Reprocessing Worth The Risk?

- ↑ Plutonium proliferation and MOX fuel

- ↑ Podvig, Pavel (10 March 2011). "U.S. plutonium disposition program: Uncertainties of the MOX route". International Panel on Fissile Materials. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Information from the World Nuclear Association about MOX".

- ↑ "Candu works with UK Nuclear Decommissioning Authority to study deployment of EC6 reactors". Mississauga: Candu press-release. June 27, 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ↑ "Swords into Ploughshares: Canada Could Play Key Role in Transforming Nuclear Arms Material into Electricity," in The Ottawa Citizen (22 August 1994): "CANDU ... reactor design inherently allows for the handling of full-MOX cores"

- ↑ TVA might use MOX fuels from SRS, June 10, 2009

- ↑ New Doubts About Turning Plutonium Into a Fuel, April 10, 2011

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 "NDA Plutonium Options" (PDF). Nuclear Decommissioning Authority. August 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-07

- ↑ "Thorium test begins". World Nuclear News. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

External links

- Technical Aspects of the Use of Weapons Plutonium as Reactor Fuel

- Synergistic Nuclear Fuel Cycles of the Future

- Nuclear Issues Briefing Paper 42

- Burning Weapons Plutonium in CANDU Reactors

- Program to turn plutonium bombs into fuel hits snags

| ||||||||||||||||||