MIDI usage and applications

The two organizations responsible for the creation and oversight of the MIDI standard, the US MIDI Manufacturers Association (MMA) and Japan's Association of Musical Electronics Industry (AMEI), have jointly standardized many extensions to it. General MIDI (GM) is one of these, an attempt by the MMA to create a standardized map of instrument programme numbers. AMEI members developed General MIDI Level 2 (GM2), which increased the number of available instruments, specified additional message responses, and defined new messages. GM2 is the basis of the instrument selection mechanism in Scalable Polyphony MIDI (SP-MIDI), a MIDI variant for mobile applications. The hardware connection specified in the original standard has been augmented with support for additional forms of transport. MIDI is also used as a control protocol in applications other than music, including show control and theatre lighting.

Extensions of the MIDI standard

Only a few extensions of the original official MIDI 1.0 specification are described here; for more comprehensive information, see the MMA web site.

General MIDI

The General MIDI (GM) and General MIDI 2 (GM2) standards specify how a MIDI device will respond when it receives a defined set of MIDI messages. These standards ensure that a MIDI stream will be played in a consistent manner on any conformant instrument. The GM and GM2 specifications are dependent on the basic MIDI 1.0 specification, but separate from it, so that is not generally safe to assume that any given MIDI message stream or MIDI file will be handled in the expected way by GM-compliant or GM2-compliant MIDI instruments.

These specifications resolve ambiguities in the MIDI message protocol. In MIDI, instruments are arranged one-per-channel, and are selected by program change messages using the numbers 0-127. MIDI 1.0 does not define which instrument sound (piano, tuba, etc.) corresponds to each number. This was due to MIDI's origin as a professional music protocol, and was intended to allow a performer to assemble a custom palette of instruments appropriate for their particular repertoire.

MIDI was later adopted as a consumer content format, and for computer multimedia applications. In order for MIDI file content to be portable, the instrument program numbers used must call up the same instrument sound on every player. The MMA addressed this problem with the 1991 introduction of GM. GM standardises an instrument programme number map, which specifies that a given program change number will select the same instrument sound on every GM-compatible device. For example, a program change message with a value of "1" results in a piano sound on all GM-compliant players. GM also specified the response to certain other MIDI messages in a more controlled manner than the MIDI 1.0 specification. The GM spec is maintained and published by the MMA.

GM has a mixed reputation, mainly because of audible differences between instrument sounds across player implementations, the limited size of the instrument palette (128 instruments), and the inability to add customised instruments to suit the needs of the particular piece. The GM instrument set is nevertheless included in most MIDI instruments, and GM has proven to be a durable standard.

General MIDI 2

Companies in Japan's AMEI later developed General MIDI Level 2 (GM2), which incorporated aspects of the Yamaha XG and Roland GS formats. GM2 provides for expansion of the instrument palette, specifies more message responses in detail, introduces messages that allow custom tuning scales, and more. The GM2 specs are maintained and published by the MMA and AMEI. General MIDI 2 was introduced in 1999, and last amended in February 2007.

SP-MIDI

GM2 is the basis of the instrument selection mechanism in Scalable Polyphony MIDI (SP-MIDI), a MIDI variant for mobile applications in which different players may have different numbers of musical voices. SP-MIDI is a component of the 3GPP mobile phone terminal multimedia architecture, as of release 5. GM, GM2, and SP-MIDI are also the basis for the selection of player-provided instruments in several MMA/AMEI XMF file formats (XMF Type 0, Type 1, and Mobile XMF), which allow the instrument palette to be extended with custom instruments in the Downloadable Sound (DLS) formats. This addresses GM's lack of support for customized instruments.

Alternate Hardware Transports

In addition to the original 31.25 kbit/s current-loop signal that terminates in a 5-pin DIN connector, transmission of MIDI streams over USB, IEEE 1394/FireWire and Ethernet is now common.

MIDI over Ethernet

The Ethernet implementation of MIDI provides useful network routing capabilities which are not possible with the peer-to-peer USB and FIreWire technologies. Ethernet is moreover capable of providing the high-bandwidth channel that earlier alternatives to MIDI (such as ZIPI) were intended to bring. After an initial battle among competing protocols, the RTP-MIDI specification for transport of MIDI over Ethernet and the Internet is gaining industry support. Drivers available for the Macintosh, Windows and Linux operating systems allow RTP-MIDI devices to be addressed as standard MIDI devices.

RTP-MIDI Transport Protocol

The RTP MIDI protocol was released to the public domain by IETF in December 2006 (RFC 4695), and was supplanted in June 2011 by RFC 6295, which corrects the original's errors. RTP-MIDI relies on the Real-time Transport Protocol (RTP) layer that is in wide use for real-time audio and video streaming over networks. The RTP layer is lightweight and easy to implement, and provides the receiver with useful information regarding the network state. RTP-MIDI defines a specific payload type that allows the receiver to identify MIDI streams. It transports MIDI messages unaltered, but adds functionalities such as timestamping and sysex fragmentation, and journaling, which allows the receiver to detect the loss of MIDI messages in the network and to retrieve lost information.

The first part of the RTP-MIDI specification describes how MIDI messages are encapsulated within the RTP telegram, and describes how the journaling system works. Use of the journaling system is not mandatory, as journaling is not useful for LAN applications, but is important for WAN applications. The second part of the specification describes the session control mechanisms that allow multiple stations to synchronize across the network to exchange RTP-MIDI telegrams. This part is informational only, and it is not required that all RTP-MIDI implementations use the described mechanisms.

RTP-MIDI has been included in Apple's Mac OS X since 10.4 and iOS since 4.2 as standard MIDI ports. The RTP-MIDI ports appear in Macintosh applications as any other USB or FireWire port, so any MIDI application running on Mac OS X is able to use the RTP-MIDI capabilities in a transparent way. Apple's developers have created their own session control protocol, as they felt the one described in IETF's specification was too complex. Since the session protocol uses a different UDP port of the main RTP-MIDI stream port, the two protocols do not interfere, and the RTP-MIDI implementation in Mac OS X fully complies to the IETF specification.

Apple's implementation has been used as a reference by other MIDI manufacturers. A Windows RTP-MIDI driver[1] compatible with Windows XP through Windows 7 (32bit and 64bit) has been released, the Dutch company Kiss-Box has produced a Windows XP RTP-MIDI driver for their own devices, and a Linux implementation is under development by the Grame association. It is probable that Apple's implementation will become the "de facto" standard, and could even become the MMA reference implementation.

Alternate Tunings

Instruments that receive MIDI conventionally use the 12-pitch per octave equal temperament tuning system, which renders music that depends on a different intonation system inaccessible. The MMA addressed this issue with the 1992 ratification of the MIDI Tuning Standard, or MTS. MIDI instruments that support MTS can be tuned in any way desired, through the use of a MIDI Non-Real Time System Exclusive message.

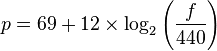

MTS specifies a pitch in logarithmic form through a three byte message which can be thought of as a three-digit number in base 128. The byte values necessary to encode a given frequency in hertz are determined by the following formula:

For a note in A440 equal temperament, this formula delivers the standard MIDI note number. Other frequencies fill the space evenly.

Support for MTS is not particularly widespread in commercial hardware instruments. Programs that support MTS include the free software programs TiMidity and Scala, as well as other microtuners.

Other applications of MIDI

MIDI is also used every day as a control protocol in applications other than music, including:

- show control

- theatre lighting

- special effects

- sound design

- Console automation

- recording system synchronization

- audio processor control

- computer animation

- computer networking, as demonstrated in 1987 by the early first-person shooter game MIDI Maze

- animatronic figure control

Non-musical applications of MIDI are possible because any device built with a standard MIDI Out connector should in theory be able to control any other device with a MIDI In port, as long as the developers of both devices agree on the meaning of the MIDI messages the sending device emits. This agreement can come either because both follow the published MIDI specifications, or in the case of non-standard functionality, because the message meanings are agreed upon by the two manufacturers.

MIDI controllers

The term "MIDI controller" is used in two different ways. A MIDI controller can be defined as hardware or software that is able to transmit MIDI messages via a MIDI Out connector to other devices with MIDI In connectors. In the other, more technical sense, a MIDI controller is a parameter that can be controlled remotely through MIDI Control Change messages. For example, synthesizers commonly use controller number 74 to control a low-pass filter's frequency. If a user assigns a physical slider to transmit controller number 74, then all changes in the slider position will be transmitted as MIDI Control Change messages on controller number 74, and the synthesizer's filter frequency will change accordingly.

MIDI controllers which are hardware and software

The following are types of MIDI controller, according to definition 1 above:

- The human interface component of a traditional instrument, redesigned as a MIDI output device. Most commonly, the keyboard controller. Such a device provides a musical keyboard, and often other actuators such as pitch bend and modulation wheels, but produces no sound on its own and is intended only to drive other MIDI devices. Percussion controllers such as the Roland Octapad fall into this class, as do guitar-like controllers such as the SynthAxe, and a variety of wind controllers.

- Electronic musical instruments, including synthesizers, samplers, drum machines, and electronic drums, which are used to perform music in real time and are able to transmit a MIDI data stream of the performance.

- Pitch-to-MIDI converters such as guitar synthesizers analyze a pitch and convert it into a MIDI signal. Several devices do this for the human voice and for monophonic instruments such as flutes.

- Traditional instruments such as drums, pianos, and accordions that are outfitted with sensors, whose output is processed and transmitted as MIDI data.

- Sequencers, which store and retrieve MIDI data, and then send the data to MIDI-enabled instruments in order to reproduce a performance.

- The MIDI Show Control (MSC) protocol is an industry standard, ratified in 1991 by the MIDI Manufacturers Association, which allows all types of media control devices to work together to perform show control functions in live and recorded entertainment applications. Just as in musical MIDI, MSC does not transmit the actual show media, but instead transmits digital data containing information such as the type, timing and numbering of technical cues called during a multimedia or live theatre performance.

- MIDI Machine Control (MMC) devices such as recording equipment, which transmit messages for synchronization of MIDI-enabled devices. For example, a recorder that has a feature to index a recording by measure and beat can be synchronized with a sequencer.

MIDI controllers in the data stream

This section uses the second definition of "MIDI controller".

Performance modifier controls such as modulation wheels, pitch bend wheels and ribbon controllers alter an instrument's state of operation, and can be used to modify sounds or other parameters of a musical device. MIDI includes messages that represent such controller events, and they can be sent in real time over MIDI connections. MIDI makes approximately 120 virtual controller numbers available for this purpose. The value data range of the MIDI Control Change message is 128 steps (0 to 127). The first 32 controller numbers are allocated an additional 7 bits of precision for a total of 14 bits, which provides a range of 0-16383, although many manufacturers do not implement this increased resolution.

Some controller functions, such as pitch bend or key pressure, are given a dedicated MIDI data range of 16,384 steps. This higher resolution makes it possible to produce the illusion of a continuously sliding pitch, as in a violin's portamento, rather than a series of zippered steps, such as a guitarist sliding fingers up the frets of the guitar's neck. Pitch bend and key velocity use different, dedicated messages, such as Polyphonic Key Pressure, Channel Pressure, or Pitch Bend Change, rather than the ordinary Control Change message. There is a disadvantage, in that the pitch wheel and/or key pressure functions of a MIDI keyboard can generate large amounts of data that can lead to a slowdown of data throughput on the MIDI connection. This can be remedied by using a sequencer to filter continuous controller data down to a limited number of messages per second, or to messages that change the controller value by a minimum amount.

The original MIDI specification included approximately 120 virtual controller numbers for real-time modifications of live instruments or their audio. MSC and MMC are two separate extensions of the original MIDI specification, and expand the MIDI protocol beyond its original intent.

See also

- Mobile phone ringtone

- Pulse-code modulation (PCM)

- show control