Lysippides

The Lysippides Painter worked in Athens in the second half of the 6th century BC. He was a black-figure painter of a classic style. He most probably trained with Ezekias in his workshop until moving to the Andokides workshop where he mainly painted large, expensive vases and did some work on bilingual vases with Andokides P being the red-figure painter. He was named, after much debate ensuring he was not the Andokides Painter using red-figure, after a Kalos found on one of his vases.

Common Themes of Lysippides

Amphorae

Of the 204 Vases attributed to Lysippides P in the Beazley archives, 112 are large amphorae. These contain all variations of Amphorae, Amphora A, Amphora B, Amphora Neck, and 4 Panathenaic Amphorae.

Cups

There are also 32 cups consisting of Cup A and Little Master Band Variations. These are large cups, and many hold the face of a gorgonian in the basin. These Gorgonians are typical of the Nikostenes workshop which it is believed Lysippides was lent to on occasion.

Other Shapes

Some of the other shapes that Lysippides works with are Krater, Columns, Oinchoes, Psykters, and Pyxis. These shapes have very small numbers, but many of them carry the same subjects as those of other Lysippides vases.

Provenance

Most of these vases appear to have been traded to Italy, especially the area around Rome, Etruria. Of the 85 vases that have listed provenances, 74 were shipped to Italy and over of 50 of these to the Etruria region. The other provenances include Sicily, Egypt and Turkey, but they appear in nominal numbers.

Subjects

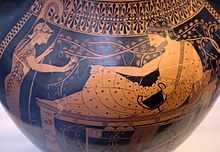

Herakles is clearly the favorite subject of the Lysippides Painter. IT is also a favorite of most Group E vase-painters.[1] Of the 204 vases in the Beazley Archive there are over 60 of Herakles in various forms of heroism, fighting the lion, mounting chariots with Athena, fighting Amazons (Amazonomachy), and fighting giants (Giantomachy). He is almost always shown in his lion cape, with hood resting on the back of his black hair, defined with white paint. The arms of the lion are tied around his chest (where muscles are also well defined with white lines).

Warriors and fights are equally important in Lysippides' vases. Some show warriors fighting over a fallen soldier, others show battles. Almost all soldiers have Boeotiaon shields and spears, many with Corinthian helmets. They are typical of ancient Greek vases, and show glory, arête and honor, all values held high by the Greeks.

Other subjects include Amazonomachys, Giantomachys and scene with Dionysos, often surrounded by the double-leafed vine.

While the shape of the vase is mostly considered to be chosen by the workshop, the subject could very well have been the decision of the artist himself. While these subjects chosen are typical of many Greek vases the prevalence of Herakles in Lysippides vases is certainly significant of both his style and interests. Perhaps he was commissioned for his fine work in the painting of Herakles. Certainly, the images are tenderly rendered with exquisite detail.

Lysippides and Andokides

It is very probable that Lysippides painter worked mostly in the Andokides workshop. The Andokides workshop was known for it more high quality pieces and Lysippides was a highly skilled black-figure painter of the time. One of the styles that came from the Andokides workshop was the bilingual vase. Beth Cohen, in 'Colors of Clay' suggests that Andokides was one of the first red-figure painters and suggests that he may have even been an inventor of the style. While creating bilingual vases with different black-figure painters, such as Lysippides, Andokides would paint one side of the vase in red-figure and another painter would paint the other in black-figure. In the case of cups, often the red-figure painter would paint the inside and the black-figure painter would paint the outside.[2]

There are six bilingual vases in the Beazley Archives attributed to both Andokides P and Lysippides P. Many archeologists have debated the validity of the bilingual vase, suggesting that one painted both styles. However Cohen, with the assistance of other such as Mary B Moore, points out some general differences that distinguish the two styles. For instance, they claim that the Andokides painter uses larger more lifelike images and with less detail. The Lysippides painter is suggested to be more old fashioned, painting with clear influence of his teacher Ezekias.

While Cohen and Moore seem to consider the newly discovered technique to be more advanced and lifelike that the older black-figure style, there is something to be said for the detail and care that is clear from the stylized black-figure that adds a dimension that the red-figure is lacking. Of course, because red-figure painting was new its distinct style may not have evolved to the stage that black-figure had the chance to in their longer history.[3]