Lygodactylus williamsi

| Lygodactylus williamsi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Sauria |

| Infraorder: | Gekkota |

| Family: | Gekkonidae |

| Subfamily: | Gekkoninae |

| Genus: | Lygodactylus |

| Species: | L. williamsi |

| Binomial name | |

| Lygodactylus williamsi Loveridge, 1952 | |

| |

Lygodactylus williamsi is a species of lizard endemic to Africa. Common names include turquoise dwarf gecko, William's dwarf gecko, or, in the pet trade, electric blue gecko.[2]

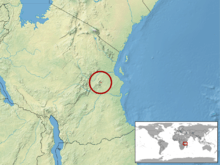

Geographic range

L. williamsi is only found in 8 km² (3 sq mi) of the Kimboza Forest in eastern Tanzania.

Conservation status

This gecko's survival is threatened by (entirely illegal) collection for the international pet trade,[2] and its tropical forest habitat is shrinking and fragmenting. It is critically endangered and the population is thought to be declining rapidly.[1] The subpopulation in Kimboza Forest Reserve was estimated at 150,000 adults in 2009. The size of the remaining subpopulations (Ruvu Forest Reserve and two smaller ones outside protected areas) is unknown, but their size is not thought contribute significantly to the total population.[1] Neither of the reserves where it occurs is well-protected.[1]

Etymology

The specific name, williamsi, given to the gecko by British zoologist Arthur Loveridge,[3] honours American herpetologist Ernest Edward Williams.[4]

Description

Males are bright blue with heavy black throat stripes, visible preanal pores, and hemipenile bulges. The females range from brown or bronze to bright green, and have little to no black on their throat. Females can easily be confused with juvenile or socially suppressed males that are also green, sometimes with a bluish cast. The underside of both sexes is orange. Colours of individuals vary according to mood and temperature. Males may range from black or gray to brilliant electric blue. Females may range from dark brown to brilliant green with turquoise highlights. Adult snout-vent length is 5 to 8 cm (2.0 to 3.1 in).

Ecology

In the wild, turquoise day geckos live exclusively on the (endangered) screwpine, Pandanus rabaiensis,[2] mostly in the leaf crown. They eat small insects and drink water from leaves. They are also fond of nectar.

Behavior

Like all geckos of the genera Lygodactylus and Phelsuma, this species is diurnal. They are bold, active, social, and males are territorial. Social gestures include lateral flattening, puffing out of the throat patch, head shaking and head bobbing, and tail-wagging.

Reproduction

Males court females with lateral flattening, puffing out of the throat pouch, and head bobbing. Two to three weeks after copulation, the female lays a clutch of 1 or 2 pea-sized white, hard-shelled eggs which are glued to a surface in a secure, hidden location. Eggs hatch in 60 to 90 days.

Threats

Although there are no legally wild-caught turquoise day geckos, wild-caught geckos are commonly sold in pet shops. It is estimated that between December 2004 and July 2009, at least 32,310 to 42,610 geckos were taken by one collecting group, ~15% of the wild population at the time.[2]

Collectors commonly cut down the screwpine trees to reach the geckos living in the leaf crest, destroying the gecko's habitat. Many geckos are thought to die while being shipped to market. The pet trade is likely a worse threat than even habitat loss.[2]

Most of the remaining forest is in Catchment Forest Reserves,[5] but is still seriously threatened by clearing for farmland, illegal logging, increasingly frequent fires, and mining of the limestone outcrops on which the screwpines grow.[1] There is little forest left unaffected.[5]

In captivity

These tiny lizards are generally housed in planted tropical vivariums or vertical (tall) terrariums. Provided with UV-B (mid spectrum) light and an (UV-A) basking spot, daytime temperatures of 75.2 F (24.0 C) to 86 F (30.0 C), and night-time lows of 64.4 F (18.0 C) to 71.6 F (22.0 C), they have proven to be fairly hardy. Humidity should range from 50% to 85%.

Misting twice a day provides water for drinking, but these geckos have also been seen frequently drinking from small cups or from bromeliad bases. They will eat a wide variety of insects including fruit flies, mini-mealworms, phoenix worms, small silkworms, roach nymphs, and crickets up to 1/4" in size. Daily supplementation of insects with phosphorus free calcium and vitamin supplements is vital. Supplemented fruit puree or a commercial MRP (meal replacement powder, which is prepared with water) made for crested geckos or day geckos is readily accepted. Food offerings must be limited to avoid obesity, and feeding 3 times per week is sufficient when using MRP.

Only one male should be housed per group, to avoid dangerous aggression. Multiple feeding stations will help to avoid excessive aggression between females.

These geckos breed readily in captivity, when they are satisfied with their environment and properly cared for. The eggs can be hatched in an incubator or in the enclosure. Incubated eggs hatch in about 80 days at 27 degrees Celsius (80.6 F). Eggs left in the enclosure will hatch in about 100 days. It takes longer because of the fluctuating temperatures at day and night. But the hatchlings are often stronger. Glued eggs should best be left inside the terrarium, because they could crack while removing them. But be aware of predators (like their parents!) when hatched, so gently remove them as soon as possible to a new environment. Best use relatively large enclosures like 15 x 30 x 30 cm (6 x 12 x 12 inches) in size, with 2-3 hatchlings per enclosure.

These small geckos are remarkable for their virtually fearless nature, and quickly tame. Handling is not recommended for such small animals, but they can be lured onto their keeper's hands with insect treats, and will remain active and behave naturally while being observed, once they are acclimated to captivity (often as quickly as one month after introduction to their enclosure).

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Flecks M, Weinsheimer F, Böhme W, Chenga J, Lötters S, Rödder D, Schepp U, Schneider H. (2012). "Lygodactylus williamsi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Flecks M, Weinsheimer F, Boehme W, Chenga J, Loetters S, Roedder D. (2012). (FULL TEXT) "Watching extinction happen: the dramatic population decline of the critically endangered Tanzanian Turquoise Dwarf Gecko, Lygodactylus williamsi.". Salamandra 48 (1): 12-20.

- ↑ Loveridge A. (1952). A startlingly turquoise-blue gecko from Tanganyika. Journal of the East African Natural History Society 20: 446. (cited in the IUCN database as the species authority).

- ↑ Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M. (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Lygodactylus williamsi, p. 286).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Burgess, Neil; Doggart, Nike; Lovett, Jon C. (2002). "The Uluguru Mountains of eastern Tanzania: the effect of forest loss on biodiversity". Oryx 36.2: 140-152.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lygodactylus williamsi. |

- UNEP-WCMC Species Database

External links

- The Reptile Database entry: http://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/species?genus=Lygodactylus&species=williamsi

- Catalogue of Life taxonomic entry: http://www.catalogueoflife.org/col/details/species/id/13201544

- Der Türkisblaue Zwerggecko Lygodactylus williamsi. ISBN 978-3-86659-173-8.