Luis Arellano Dihinx

| Luis Arellano Dihinx | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Luis Arellano Dihinx 1906 Zaragoza, Spain |

| Died |

1969 Pamplona, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Ethnicity | Spanish |

| Occupation | lawyer |

| Known for | Politician |

Political party | Comunión Tradicionalista, FET |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Luis Arellano Dihinx (Zaragoza, 1906 – Pamplona, 1969) was a Spanish Carlist and Francoist politician.

Family and Youth

Luis Arellano Dihinx was born to a bourgeoise Navarrese family, son of Cornelio Arellano Lapuerta and Juana Dihinx Vergara (who outlived her son by 6 months). His father was a civil engineer engaged in a number of construction projects. His works ranged from Irati Train, the railroad line connecting Pamplona and Sangüesa across a difficult, wooded and hilly Irati terrain, to hydrotechnical constructions on the Ebro and other rivers. He was also a co-founder and a co-owner of Múgica, Arellano y Compañía, the Pamplona-based company which produced and traded agricultural machninery and existed into the late 20th century.

Luis had 4 brothers; two of them were killed during the Civil War by the Republican militia in the Angeles Custodios Bilbao prison early 1937, one was later to become a Jesuit friar and another one a construction engineer. Luis studied law and economics in the Deusto Jesuit college in Bilbao. Upon his return to Pamplona he commenced minor career engagements, more and more frequently interrupted by his political activities. Married to María Dolores Aburto Renobales (February 1936); the couple had 4 sons, all of them professionals not engaged in politics.

Republic

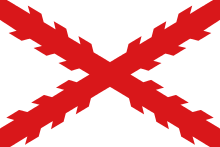

Following the fall of the monarchy of Alfonso XIII and proclamation of the Republic in 1931, Arellano sided with the ultraconservative, antidemocratic Carlist movement and got engaged in the Carlist militia Requetés, at that time organized in 10-man squads known as decurias and headed by Eugenio Sanz de Lerín. He soon emerged as one of the leaders of the Pamplona youth, though tending to excel in politics rather than in the military issues. He endorsed violent subversive anti-Republican strategy, assuming that the ensuing official repressions were merely strengthening the organization.

Appreciated and promoted by the then Carlist leader Conde Rodezno, during the 1933 elections to the Cortes Arellano was offered a comfortable position on the Navarrese list of candidates. He was elected with 72 thousand votes and together with José Luis Zamanillo became one of the youngest Traditionalist deputies ever. In accord with the monarchists from other groupings, briefly engaged in Grupo Social Parliamentario, he aimed at publicizing social-Catholicism and at sponsoring Catholic rivals to the Anarchist and Socialist trade unions. As a Rodezno disciple and unlike intransigent youths led by Jaime del Burgo, Arellano became involved in alliance with the Alfonsists known as Bloque Nacional. When Manuel Fal Condé replaced Rodezno as the Carlist leader in 1934, Arellano was named head of the newly created Youth Section. Initially it controlled Juventud Tradicionalista, AET and Requeté organizations, though there was later another separate section created for the militia. In 1936 he was re-elected to the Cortes from the same Navarrese constituency.

Civil War

Arellano was heavily involved in conspiracy to overthrow to Republic. During the hectic July 1936 last-minute political negotiations between the Carlist leadership and the army conspirators he preferred that the military be lent outright support. As Rodezno’s confidant he formed a pressure group which travelled to France to seek the authorization from the envoy of the claimant, Don Alfonso Carlos. The approval, though given hesitantly, proved crucial in outmanoeuvring Fal Condé, who insisted that the generals accept the Carlist conditions first.

Following the outbreak of hostilities and a relatively smooth seizure of Navarre by the rebels, Arellano fought as a Requeté officer in Sierra de Guadarrama, unsuccessfully trying to break through defence lines held by the socialist militia. Early 1937 he was withdrawn from the frontline in the rank of a captain to undertake political tasks during the Franco-administered campaign of unification with the Falange.

Having been part of the pro-unification rodeznistas, Arellano was on different occasions active in what amounted to a coup within Carlism, pushing Fal Condé into minority. As a result in April 1937 the intransigent falcondistas and the new regent-claimant, Don Javier, were forced into silence while the unification proceeded.

Within the new united organization, Falange Española Tradicionalista, Arellano was among 4 Carlists who entered Secretariat, a makeshift body hastily created by Franco as the façade executive structure. In November 1937 it was supplemented by a 50-member Consejo Nacional, with 11 Carlists (Arellano included) forming part. Don Javier and Fal Condé considered him one of the key rebels against their authority, but had few if any means at their disposal to enforce obedience. Early 1938, when Rodezno assumed the Ministry of Justice in the first Francoist government, Arellano followed him as subsecretary - the post initially offered to José María Valiente, but rejected - and held it until the cabinet was reorganized and Rodezno replaced by Esteban Bilbao in August 1939.

Dynastical issues

.jpg)

Due to the unification already at odds with the regent-claimant Don Javier, Arellano followed Rodezno drawing nearer the Alfonsist pretender, Don Juan. Both visited him in Portugal in 1946, discussing terms for his possible reconciliation with Carlism and demonstrating only notional loyalty to the official Traditionalist regent. Though technically the regency allowed Carlists to go on forming factions around prospective kings, courting Don Juan amounted to political pressure and cornered the half-abandoned Don Javier even more.

In 1952, following the death of his mentor Rodezno, Arellano became an informal leader of the Don Juan supporters, though he still fell short of abandoning the regency altogether. The same year Don Javier gave way to his supporters – partially to counter another claimant touted by the Falange, Karl Pius Habsburg – and terminated the regency by announcing his own claim to the throne.

The stalemate lasted 5 years, at times looking as Don Javier might backtrack. However, when during the May 1957 annual Carlist Montejurra amassment his son, Carlos Hugo, made a fulminant Principe de Asturias entry greeted by exploding enthusiasm of the youth, the supporters of Don Juan mounted a counter-action. Arellano presided over the delegation of forty-four Carlist juanistas, who visited Don Juan in his Estoril residence. The Alfonsist claimant, wearing the red beret, swore his allegiance to the principles of Traditionalism, an act repeated a year later in Lourdes, and was accepted as a legitimate Carlist successor in return. Arellano himself entered the Private Council of the pretender.

Due to his pro-juanist and pro-Francoist stand, during the 1958 Montejurra feast Arellano was threatened by the angry Carlist youth. He had to leave protected by Guardia Civil. The event was a symbolic defeat of the juanistas. From this moment onwards the Carlist movement was increasingly taken over by the javieristas and then by the young supporters of Carlos Hugo. Oddly enough, hostility towards the pro-regime juanistas produced a brief rapprochement with socially-radical Falangists; it was only later that hugocarlistas took an increasingly Leftist turn until its full conversion to carlomarxism in the early 1970s.

Arellano retained his loyalty to Don Juan until his death, though in the 1960s he was apparently puzzled by the ever-more likely perspective that Don Juan would by bypassed and the crown would go to his son, Juan Carlos de Borbón.

Francoism

Though initially supporter of the unification and member of the Francoist partido unico executive, later Arellano lost his enthusiasm and was keen to preserve some degree of identity of the Carlist movement. To prevent total incorporation of its press into the Falangist propaganda machine, he formed part of the Editorial Navarra board, a largely fictitious company created by the Traditionalists to save at least the Pamplona-based daily, El Pensamiento Navarro; Arellano kept 150 of the 600 shares. The newspaper was indeed spared amalgamation into the Francoist press, though the measure adopted left it firmly under control of the rodeznistas and the daily had to submit to the usual censorship pressure anyway.

In the early 1940s Arellano, holding nominal positions in the national Francoist structures, played major role only in the Carlist and the local Navarrese politics. In the former his activity was aimed at keeping the falcondistas in check, in the latter it was staged to prevent the Falangists from overwhelming the province. It was thanks to the lobbying of Rodezno, Arellano and other collaborative Carlists that Navarre and Álava retained some autonomous establishments as the only provinces in the Francoist Spain. In 1947 he presided over the congress of regionalist lawyers in the Catalan Monastery of Montserrat, a meeting which produced a document recommending recognition of the traditional fueros.

As a lawyer Arellano became assessor to the Navarrese Diputación Foral, remained active as a councilor in the Pamplona ayuntamiento until 1955 and was the dean of the Navarrese Colegio de Abogados. At all these positions he tried to repel the Falangist takeover of the local administration, led by the FET civil governors of the province. The conflict climaxed in 1954 when the Falangist Gobernador Civil, Luis Valero Bermejo, requested of the Ministry of Interior that special measures are employed, including sanctions to be taken against Arellano himself. The showdown ended with Bermejo recalled to Madrid and total victory of the Navarrese.

In the early 1950s Arellano resumed his deputy career by entering the Francoist quasi-parliament. Though he was ignored in course of the first 3 turns, in 1952 he entered Cortes Españolas from a pool reserved for the personal Franco’s appointees. He retained the mandate during the next 4 terms and 15 years, active mostly in the committees dealing with the legal system, though lacking sufficient weight to engage in the backstage political haggling. In 1967 he was still a member of the Comisión de Leyes Fundamentals, busy discussing a new Ley Organica del Movimiento. In 1966 he suffered injuries in a car accident in Pamplona; after that, he started to withdraw from public life, though retaining some business engagements, e.g. in the municipal Savings Bank.

Other

.jpg)

In 1952 Arellano received Gran Cruz de la Orden de San Raimundo de Peñafort. In 1969, shortly after his death, he was named hijo predilecto by the Navarre province. In 2008 the Audiencia Nacional judge Baltazar Garzon posthumously raised the crimes against humanity case against Arellano; the charges related to his tenure in the Ministry of Justice in 1938-1939.

See also

References

- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 1975, ISBN 9780521207294

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis], Valencia 2009

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, Retorno a la lealtad; el desafío carlista al franquismo, Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788497391115

- Maria del Mar Larazza Micheltorena, Alvaro Baraibar Etxeberria, La Navarra sotto il Franchismo: la lotta per il controllo provinciale tra i governatori civili e la Diputacion Foral (1945-1955), [in:] Nazioni e Regioni, Bari 2013, ISSN 22825681

- Roberto Villa Garcia, Las Elecciones de 1933 en El País Vasco y Navarra, Madrid 2006

- Aurora Villanueva Martinez, El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714

- Aurora Villanueva Martinez, Organizacion, actividad y bases del carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo [in:] Geronimo de Uztariz 19, pp. 97–117

External links

- Historical Index of Deputies

- Luis Arellano on euskomedia

- Luis Arellano on geni

- Luis Arellano on Gran Enciclopedia Navarra

- Cornelio Arellano on Gran Enciclopedia Navarra

- info on El Pensamiento Navarro

- 1947 foralist document by Arellano

- Carlist Navarrese organisation during early Francoism

- Carlist and Falangist struggle for power in Navarre

- Carlist struggle for identity under Francoism

- Carlos Hugo triumphant at Montejurra 1960s (movie) on YouTube

- Arellano nephew on his uncle

- Memoria Histórica site dedicated to the victims of Francoism

- auto by judge Garzon against Arellano and others

- Vizcainos! Por Dios y por España; contemporary Carlist propaganda