Luba Crater Scientific Reserve

| Luba Crater Scientific Reserve | |

|---|---|

|

Forest near the village of San Antonio de Ureca, in the south of the reserve | |

| |

| Coordinates | 3°21′12″N 8°30′47″E / 3.353377°N 8.513031°ECoordinates: 3°21′12″N 8°30′47″E / 3.353377°N 8.513031°E |

| Area | 51,000 hectares (130,000 acres) |

| Created | 2000 |

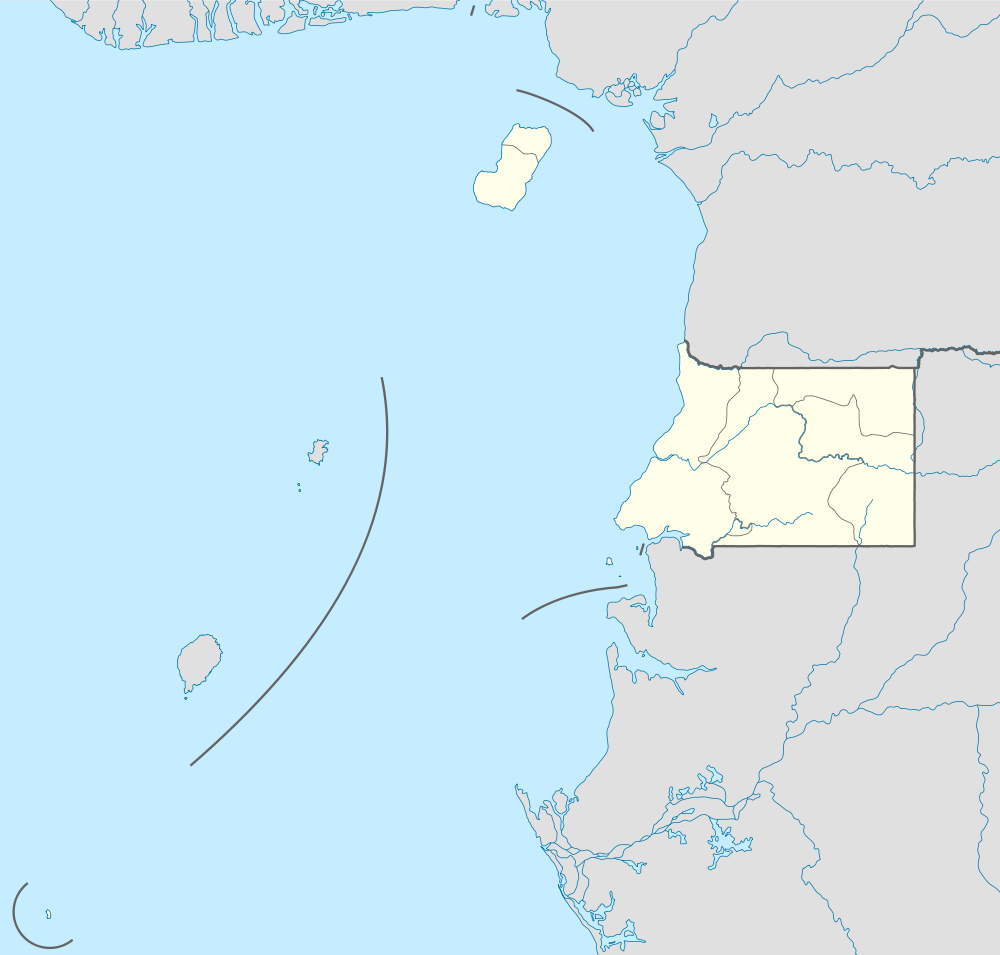

The Luba Crater Scientific Reserve (Spanish: Reserve Scientifique de la Caldera de Luba) is a protected area of 51,000 hectares (130,000 acres) on the volcanic island of Bioko (formerly called Fernando Pó), a part of Equatorial Guinea. The dense rainforest is rich in plant and animal species including a high population of primates, some endemic to the reserve.[1] Much of the reserve consists of pristine forest.[2] However, the primate population is under threat due to growing demand for bushmeat coupled with lack of enforcement of the ban on hunting in the reserve.[3]

Location

The Luba Crater Scientific Reserve is in the island of Bioko, which is part of the small country of Equatorial Guinea. Before the country gained independence from Spain in 1968 the main cash crop was cocoa. Since then agriculture has been neglected and many of the cocoa plantations have returned to the forest. Until recently a poor country, exploitation of large offshore reserves of oil and gas has dramatically increased the Gross Domestic Product. However, the government is plagued by corruption and mismanagement, and distribution of wealth is unequal. Many people still depend on subsistence agriculture.[4]

Bioko is on the African continental shelf and was probably connected to the mainland until the last ice age ended.[5] It is part of the Cameroon line, a string of volcano-capped swells that extends for almost 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) from the island of Pagalu in the southwest through to Oku on the mainland in the northeast.[6] Bioko is rugged, made up of two volcanic massifs. The Caldera de Luba is the highest point of the southern massif at 2,261 metres (7,418 ft).[5] The shield volcano, formerly known as San Carlos, has been active in the last 2,000 years. Its geology is not well known.[7] The crater has walls more than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) high and a diameter of 5 kilometres (3.1 mi).[5] The landscape is dramatic, including waterfalls cascading down the mountain slopes and black sand beaches along the shores.[1]

Prevailing humid winds give the mountain an exceptionally wet climate.[5] Up to 10,000 millimetres (390 in) of rain may fall in one year.[8] Temperatures in the lower regions range from 17 °C (63 °F) to 34 °C (93 °F)[9]

Environment

The forests in the reserve have been largely untouched, particularly on the wetter southern slopes of the mountain.[10][5] At the lower levels, below 700 metres (2,300 ft), the reserve is covered by closed rain forest rich in species of vegetation. Above this, up to 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) in elevation, there is montane forest with many creepers and epiphytes growing on the trees. The reserve also contains Araliaceae and Arecaceae (palm tree) forests.[1] The original lowland rain forests typically have tall trees of up to 50 metres (160 ft) emerging from a canopy of around 30 metres (98 ft). The understory is relatively sparse. The most dominant trees are in the Ficus genus. Other trees belongs to the Chrysophyllum, Milicia, Ricinodendron and Euphorbiaceae genera. [11]

The Gran Caldera de Luba has much the highest density of fauna on the island due to its inaccessibility to hunters, who must walk for two days to reach the crater.[12] A 2001 report said that 120 species of birds had been identified so far, including 36 that are endemic races on Bioko. Fernando Po Batis is an endemic species found only in the lowland forest. Larger hunted species such as black-casqued wattled hornbill and hadada ibis are only found in this part of Bioko.[8] The reserve is home to Ogilby's duiker, whose long-term survival may depend on enforcement of protection in the Gran Caldera de Luba reserve.[13] Endangered green sea turtles lay their eggs in nests on the beaches.[1] Other threatened turtle species that nest on the beaches are the hawksbill sea turtle, olive ridley sea turtle and leatherback sea turtle.[8]

The density of the primate populations in the crater, at 1.2 to 3.3 encounters per square kilometer, are among the highest in Africa.[12] Five of the primate species are of global conservation concern: Preuss's monkey, red-eared guenon, black colobus, western red colobus and drill. The reserve may be home to the largest surviving population of drill.[8] According to the Primate Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission, the island is the most important location in Africa for conserving diversity of primates. Pennant's colobus, a type of red colobus, is one of the most endangered primates in the world.[14] There are no viable captive populations of the subspecies of monkey found on Bioko. Attempts to raise black colobus and red colobus in captivity have failed.[15]

Conservation efforts

The Asociación Amigos de Doñana (AAD), a Spanish Non-governmental organization, launched a program for conservation and ecotourism development on Bioko island in 1995, with focus on conservation of the green sea turtles. This was followed in 1996 and 1997 by studies of critically important areas for conservation of biological diversity involving the Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment. The AAD conservation program, a new concept to Equatorial Guinea, included plans for environmental education and ecotourism, studies of species that are unusually interesting biologically and programs to domesticate forest animals.[16]

Since 1996 a joint research program on the primate population has been carried out by Arcadia University of the US and the National University of Equatorial Guinea.[16] The Arcadia team has used innovative approaches including the use of a waterproofed computer with GPS location detection to record exactly when and where a particular animal was sighted. Thorough waterproofing was essential since, as a team member said, "this is a very wet place". It was hoped that the improvised tracking devices could be used and maintained by semi-literate local animal trackers. Initial results were extremely encouraging.[17]

A Spanish expedition of 2007 from the Technical University of Madrid is thought to be the first to have crossed the crater, considered by the local people to be a place where spirits dwell. The team used ropes to climb down the near-vertical one-kilometer high walls of the crater. On the floor of the crater their guides had to hack a path through the dense jungle with machetes. The expedition collected over 2,000 specimens of plants and animals, including 250 different types of butterfly. Perhaps 100 of the species may be new to science.[18]

Challenges

About 7,200 people live in the reserve or in nearby villages, most of whom follow traditional methods of subsistence agriculture. The region also has cocoa plantations.[16] The villagers of San Antonio de Ureca in the south of the reserve grow bananas, breadfruit, pineapple and sugar cane. Their only domestic livestock are chickens, but they trap small game such as porcupines, pangolins and pouch rats. Their main source of currency until recently came from trade in monkeys and turtles, a traditional occupation that is technically illegal. Arcadia University's Bioko Biodiversity Protection Program has provided income for about half of the adult population of the village, employed as forest guards. However, there is still some poaching of turtles and, as of 2005, funding to pay the salaries was uncertain.[19]

The AAD submitted a management plan in 1997 and began to implement its program. The plan included defined zones for traditional use by the local people, for tourist facilities and for trekking trails, with the remainder of the reserve being a restricted zone. The plan was not formally approved and the AAD work was suspended the next year.[20] There is no institution responsible for managing the reserve and the groups working there and for coordinating study results. The turtles have not been effectively protected, and are harvested by the local people.[21] Commercial hunting of birds and mammals create a conservation threat.[8]

In the early 1980s a market for commercial bushmeat developed in Malabo, the capital city on the north coast of the island. Bushmeat has become established as a luxury food. Offshore oil exploration has fed money into the economy, increasing the number of people who can afford bushmeat. Improved roads have provided easier access by hunters to remote regions such as the Luba Crater reserve.[22] As of 2010 a new highway was under construction through the reserve from Belebu to Ureca.[23]

A theoretical ban on primate hunting has had no effect since there is no enforcement by the government.[22] Shotgun hunting is becoming more common, since the high prices commanded by bushmeat easily cover the cost of the cartridge.[24] The meat of primates costs more than that of rodents and ungulates other than Ogilby's duiker. The meat of the drill, red colobus and black colobus is the most expensive.[11] A 20 kilograms (44 lb) drill commands over $250 in Malabo.[25]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Amsallem, Wilkie & Koné 2003, p. 58.

- ↑ Morell 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ Cronin 2010, p. 2.

- ↑ Equatorial Guinea.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Perez del Va 2001, p. 266.

- ↑ Burke 2001, p. 351.

- ↑ San Carlos.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Perez del Va 2001, p. 270.

- ↑ Robinson & Bennett 2000, p. 172.

- ↑ Nyhus & McGinley 2007.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Robinson & Bennett 2000, p. 170.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Robinson & Bennett 2000, p. 175.

- ↑ East 1999, p. 321.

- ↑ Cronin 2010, p. 3.

- ↑ Cronin 2010, p. 5.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Amsallem, Wilkie & Koné 2003, p. 59.

- ↑ Maykuth 2005, p. D 1-2.

- ↑ Tarvainen 2007.

- ↑ Maykuth 2005(b).

- ↑ Amsallem, Wilkie & Koné 2003, p. 59-60.

- ↑ Amsallem, Wilkie & Koné 2003, p. 60-61.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Cronin 2010, p. 6.

- ↑ Cronin 2010, p. 7.

- ↑ Cronin 2010, p. 10.

- ↑ Cronin 2010, p. 8.

- Sources

- Amsallem, Isabelle; Wilkie, Mette Løyche; Koné, Pape Djiby (2003). "Luba Crater Scientific Reserve, Equatorial Guinea". Sustainable management of tropical forests in Central Africa: in search of excellence. Food & Agriculture Org. ISBN 9251049769.

- Burke, Kevin (2001). "Origin of the Cameroon Line of Volcano-Capped Swells" (PDF). The Journal of Geology 109 (3). Bibcode:2001JG....109..349B. doi:10.1086/319977. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- Cronin, Drew (September 2010). "Opportunities Lost: The Rapidly Deteriorating Conservation Status Of The Monkeys On Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea (2010)" (PDF). Universidad Nacional de Guinea Ecuatorial, Drexel University. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- East, Rod (1999). African antelope database 1998. IUCN. ISBN 2831704774.

- "Equatorial Guinea". CIA World Factbook. CIA. FEBRUARY 21, 2012. Retrieved 2012-03-26. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Maykuth, Andrew (Jan 22, 2005). "Cyber trackers". Toledo Blade. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- Maykuth, Andrew (2005(b)). "Making conservation pay". African Conservation Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-25. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Morell, Virginia (August 2008). "Bioko Primates". National Geographic (magazine). Retrieved 2012-30-26. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Nyhus, Philip J.; McGinley, Mark (February 15, 2007). "Mount Cameroon and Bioko montane forests". Encyclopedia of Earth. World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- Perez del Va, Jaime (2001). "Equatorial Guinea". Important Bird Areas in Africa and associated islands (PDF). Birdlife International. ISBN 187435720X. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- Robinson, John G.; Bennett, Elizabeth L. (2000). Hunting for sustainability in tropical forests. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231109776.

- "San Carlos". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- Tarvainen, Sinikka (Jun 21, 2007). "Spaniards discover animal species paradise in Guinean crater". Monsters and Critics. Retrieved 2012-03-25.