Louvre Palace

| Louvre Palace | |

|---|---|

| Palais du Louvre | |

|

Night view of the Louvre Pyramid in the centre of the Napoleon Courtyard of the Palais du Louvre | |

| General information | |

| Type | Royal residence |

| Architectural style | Additions of the 13th and 14th centuries: Gothic, Additions of the 16th century: Renaissance, Additions of the 17th and 18th centuries: Louis XIII Style and Baroque, Additions of the 19th century: Neo-Classicism, Neo-Baroque and Napoleon III Style, Additions of the 20th century: Modernism |

| Construction started | 1202 (Louvre Castle), 1546 (Louvre Palace) |

| Completed | 1989 (completed by the Louvre Pyramid) |

The Louvre Palace (French: Palais du Louvre, IPA: [palɛ dy luvʁ]) is a former royal palace located on the Right Bank of the Seine in Paris, between the Tuileries Gardens and the church of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois. Its origins date back to the medieval period, and its present structure has evolved in stages since the 16th century. It was the actual seat of power in France until Louis XIV moved to Versailles in 1682, bringing the government with him. The Louvre remained the nominal, or formal, seat of government until the end of the Ancien Régime in 1789. Since then it has housed the celebrated Musée du Louvre as well as various government departments.

Description of the present-day palace

The complex

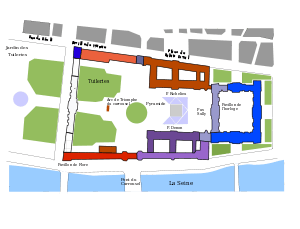

The present-day Louvre Palace is a vast complex of wings and pavilions on four main levels which, although it looks to be unified, is the result of many phases of building, modification, destruction and restoration. The Palace is situated in the right-bank of the River Seine between Rue de Rivoli to the north and the Quai François Mitterrand to the south. To the west is the Jardin des Tuileries and, to the east, the Rue de l'Amiral de Coligny (its most architecturally famous façade, created by Claude Perrault) and the Place du Louvre. The complex occupies about 40 hectares and forms two main quadrilaterals which enclose two large courtyards: the Cour Carrée ("Square Courtyard"), completed under Napoleon I, and the larger Cour Napoléon ("Napoleon Courtyard") with the Cour du Carrousel to its west, built under Napoleon III. The Cour Napoléon and Cour du Carrousel are separated by the street known as the Place du Carrousel.

The Louvre complex may be divided into the "Old Louvre": the medieval and Renaissance pavilions and wings surrounding the Cour Carrée, as well as the Grande Galerie extending west along the bank of the Seine; and the "New Louvre": those 19th-century pavilions and wings extending along the north and south sides of the Cour Napoléon along with their extensions to the west (north and south of the Cour du Carrousel) which were originally part of the Palais des Tuileries (Tuileries Palace), burned during the Paris Commune in 1871.

Some 51,615 sq m (555,000 sq ft) in the palace complex are devoted to public exhibition floor space.

The "Old Louvre"

The Old Louvre occupies the site of the 12th-century fortress of King Philip Augustus, also called the Louvre. Its foundations are viewable in the basement level as the "Medieval Louvre" department. This structure was razed in 1546 by King Francis I in favour of a larger royal residence which was added to by almost every subsequent French monarch. King Louis XIV, who resided at the Louvre until his departure for Versailles in 1678, completed the Cour Carrée, which was closed off on the city side by a colonnade. The Old Louvre is a quadrilateral approximately 160 m (520 ft) on a side consisting of 8 ailes (wings) which are articulated by 8 pavillons (pavilions). Starting at the northwest corner and moving clockwise, the pavillons consist of the following: Pavillon de Beauvais, Pavillion de Marengo, Northeast Pavilion, Central Pavilion, Southeast Pavilion, Pavillon des Arts, Pavillon du Roi, and Pavillon Sully (formerly, Pavillon de l'Horloge). Between the Pavillon du Roi and the Pavillon Sully is the Aile Lescot ("Lescot Wing"): built between 1546 and 1551, it is the oldest part of the visible external elevations and was important in setting the mould for later French architectural classicism. Between the Pavillon Sully and the Pavillon de Beauvais is the Aile Lemercier ("Lemercier Wing"): built in 1639 by Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu, it is a symmetrical extension of Lescot's wing in the same Renaissance style. With it, the last external vestiges of the medieval Louvre were demolished.

The "New Louvre"

The New Louvre is the name often given to the wings and pavilions extending the Palace for about 500 m (1,600 ft) westwards on the north (Napoleon I and Napoleon III following the quarter-mile-long Henry IV Seine Riverside Grande Gallerie) and on the south (Napoléon III) sides of the Cour Napoléon and Cour du Carrousel. It was Napoléon III who finally connected the Tuileries Palace with the Louvre in the 1850s, thus finally achieving the Grand Dessein ("Great Design") originally envisaged by King Henry IV of France in the 16th century. This consummation only lasted a few years, however, as the Tuileries was burned in 1871 and finally razed in 1883.

The northern limb of the new Louvre consists (from east to west) of three great pavilions along the Rue de Rivoli: the Pavillon de la Bibliothèque, Pavillon de Rohan and Pavillon de Marsan. On the inside (court side) of the Pavillon de la Bibliothèque are three pavilions; Pavillon Colbert, Pavillon Richelieu and Pavillon Turgot; these pavilions and their wings define three subsidiary Courts, from east to west: Cour Khorsabad, Cour Puget and Cour Marly.

The southern limb of the New Louvre consists (from east to west) of five great pavilions along the Quai François Mitterrand (and Seine bank): the Pavillon de la Lesdiguieres, Pavillon des Sessions, Pavillon de la Tremoille, Pavillon des États and Pavillon de Flore. As on the north side, three inside (court side) pavilions (Pavillon Daru, Pavillon Denon and Pavillon Mollien) and their wings define three more subsidiary Courts: Cour du Sphinx, Cour Viconti and Cour Lefuel.

For simplicity, on museum tourist maps, the New Louvre north limb, the New Louvre south limb, and the Old Louvre are designated as the "Richelieu Wing", the "Denon Wing" and the "Sully Wing", respectively. This allows the casual visitor to avoid (to some extent) becoming totally mystified at the bewildering array of named wings and pavilions.

The Pavillon de Flore and the Pavillon de Marsan, at the westernmost extremity of the Palace (south and north limbs, respectively), were destroyed when the Third Republic razed the ruined Tuileries, but were subsequently restored beginning in 1874. The Flore then served as the model for the renovation of the Marsan by architect Gaston Redon.

A vast underground complex of offices, shops, exhibition spaces, storage areas, and parking areas, as well as an auditorium, a tourist bus depot, and a cafeteria, was constructed underneath the Louvre's central courtyards of the Cour Napoléon and the Cour du Carrousel for François Mitterrand's "Grand Louvre" Project (1981–2002). The ground-level entrance to this complex was situated in the centre of the Cour Napoléon and is crowned by the prominent steel-and-glass pyramid (1989) designed by the Chinese American architect I.M. Pei.

History

Origin of its name

The origin of the name Louvre is unclear. The French historian Henri Sauval, probably writing in the 1660s, stated that he had seen “in an old Latin-Saxon glossary, Leouar is translated castle” and thus took Leouar to be the origin of Louvre.[1] According to Keith Briggs, Sauval's theory is often repeated, even in recent books, but this glossary has never been seen again, and Sauval's idea is obsolete. Briggs suggests that H. J. Wolf's proposal in 1969 that Louvre derives instead from Latin Rubras, meaning 'red soil', is more plausible.[2] David Hanser, on the other hand, reports that the word may come from French louveterie, a "place where dogs were trained to chase wolves".[3]

Medieval period

Fortress

In 1190 King Philip II Augustus, who was about to leave on the Third Crusade, ordered the construction of a defensive enclosure all around Paris. To protect the city against potential invaders from the northwest, he decided to build an especially solid fortress (the original Louvre) just outside one of the wall's most vulnerable points, the junction with the River Seine on the Right Bank. Completed in 1202, the new fortress was situated in what is now the southwest quadrant of the Cour Carrée. (Archaeological discoveries of the original fortress are part of the Medieval Louvre exhibit in the Sully wing of the museum.)[4][5]

The original Louvre was nearly square in plan (seventy-eight by seventy-two metres) and enclosed by a 2.6-metre thick crenellated and machicolated curtain wall. The entire structure was surrounded by a water-filled moat. Attached to the outside of the walls were ten round defensive towers: one at each corner and the centres of the north and west walls, and two pairs flanking the narrow gates in the south and east walls.[4]

In the courtyard, slightly offset to the northeast, there was a cylindrical keep (the Donjon or Grosse Tour), which was thirty metres high and fifteen metres in diameter with walls 4 metres thick. The keep was encircled by a deep, dry moat with stone counterscarps to help prevent the scaling of its walls with ladders. Accommodations in the fortress were supplied by the vaulted chambers of the keep as well as two wings built against the insides of the curtain walls of the west and south sides.[6] The castle was a fortress, but not yet a royal residence; the monarch's Parisian home at the time was the Palais de la Cité.[7]

The circular plans of the towers and the keep avoided the dead angles created by square or rectangular designs which allowed attackers to approach out of firing range. Cylindrical keeps were typical of French castles at the time, but few were the size of the Louvre's. It became a symbol of the power of the monarchy and was mentioned in the oath of allegiance to the king, even up to the end of the ancien régime, long after the Grosse Tour was demolished in 1528.[6][8]

The Louvre was renovated frequently through the Middle Ages. Under Louis IX in the mid-13th century, the Louvre became the home of the royal treasury. Under the Valois dynasty, it housed a prison and courtrooms.[9]

Royal residence

The growth of the city and the advent of the Hundred Years' War led Etienne Marcel, provost of the merchants of Paris, to construct an earthen rampart outside the wall of Philip (1356–1358). The new wall was continued and enhanced under Charles V.[8] Remnants of the wall of Charles V can be viewed in the present-day Louvre's Galerie du Carrousel.[7] From its westernmost point at the Tour du Bois, the new wall extended east along the north bank of the Seine to the old wall, enclosing the Louvre and greatly reducing its military value.[10]

After a humiliation suffered by Charles at the Palais de la Cité, he resolved to abandon it and make the Louvre into a royal residence.[7] The transformation from a fortress to a palace took place from 1360 to 1380.[10] The curtain wall was pierced with windows, new wings were added to the courtyard, and elaborate chimneys, turrets, and pinnacles to the top. Known as the joli Louvre ("pretty Louvre"), Charles V's pleasure palace can be seen in the illustration The Month of October from the Duc du Berry's Très Riches Heures.[11]

Renaissance period

Beginning in 1546, after returning from his captivity in Spain, Francis I employed architect Pierre Lescot and sculptor Jean Goujon to remove the keep and modernize the Louvre into a Renaissance style palace.[12][13] Lescot had previously worked on the châteaux of the Loire Valley and was adopted as the project architect. The new plan consisted of a square courtyard, with the main wing separated by a central staircase, and the two wings of the sides comprising a floor. Lescot added a ceiling to King Henry II's bedroom (Pavillon du Roi) that departed from the traditional beamed style, and installed the Salle des Caryatides, which featured sculpted caryatids based on Greek and Roman works.[14] Art historian Anthony Blunt refers to Lescot's work "as a form of French classicism, having its own principles and its own harmony".[14] Francis acquired what would become the nucleus of the Louvre's holdings; his acquisitions included Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa.[15]

The death of Francis I in 1547, however, interrupted the project. The architect Androuet du Cerceau also worked on the Louvre.[16]

In 1564 Catherine de' Medici directed the building of a château to the west called the Palais des Tuileries, facing the Louvre and the surrounding gardens.[12] The Palace closed off the western end of the Louvre courtyard. Catherine then took over the restoration of the entire palace. Her architect Philibert de l'Orme began the project, and was replaced after his death in 1570 by Jean Bullant.

House of Bourbon and After

The Bourbons took control of France in 1589. During his reign (1589–1610), Henry IV began his "Grand Design" to remove remnants of the medieval fortress, to increase the Cour Carrée's area, and to create a link between the Palais des Tuileries and the Louvre. The link was completed via the Grande Galerie by architects Jacques Androuet de Cerceau and Louis Métezeau.[17]

More than a quarter of a mile long and one hundred feet wide, this huge addition was built along the bank of the Seine; at the time of its completion it was the longest building of its kind in the world. Henry IV, a promoter of the arts, invited hundreds of artists and craftsmen to live and work on the building's lower floors. (This tradition continued for another 200 years until Napoleon III ended it.)

In the early 17th century, Louis XIII razed the north wing of the medieval Louvre and replaced it with a continuation of the Lescot Wing. His architect, Jacques Lemercier, designed and completed the wing by 1639 (subsequently known as the Pavillon de l'Horloge, after a clock was added in 1857.)[17]

The Richelieu Wing was also built by Louis XIII, the building first being opened to the public as a museum on 8 November 1793 during the French Revolution.[5] Louis XIII (1610–1643) completed the wing now called the Denon Wing, which had been started by Catherine de Medici in 1560. Today it has been renovated, as a part of the Grand Louvre Renovation Programme.

The Louvre under Louis XIV

In 1659, Louis XIV instigated a phase of construction under architects Le Vau and André Le Nôtre, and painter Charles Le Brun.[17][18] Le Vau oversaw the decoration of the Pavillon du Roi, the Grand Cabinet du Roi, a new gallery to parallel the Petite Gallerie, and a chapel. Le Nôtre redesigned the Tuileries garden in the French style, which had been created in 1564 by Catherine de' Medici in the Italian style; and Le Brun decorated the Galerie d'Apollon. A committee of architects proposed on Perrault's Colonnade; the edifice was begun in 1668 but not finished until the 19th century.[17][19]

Commissioned by Louis XIV, architect Claude Perrault's eastern wing (1665–1680), crowned by an uncompromising Italian balustrade along its distinctly non-French flat roof, was a ground-breaking departure in French architecture. His severe design was chosen over a design provided by the great Italian architect Bernini, who had journeyed to Paris specifically to work on the Louvre. Perrault had translated the Roman architect Vitruvius into French. Now Perrault's rhythmical paired columns form a shadowed colonnade with a central pedimented triumphal arch entrance raised on a high, rather defensive base, in a restrained classicizing baroque manner that has provided models for grand edifices in Europe and America for centuries. The Metropolitan Museum in New York, for one example, reflects Perrault's Louvre design. In 1678 the royal residence moved to Versailles and the Palais du Louvre became an art gallery.[20]

Later works

In 1806, the construction of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel began, situated between the two western wings, commissioned by Emperor Napoleon I to commemorate his military victories, designed by architect Charles Percier, surmounted by a quadriga sculpted by François Joseph Bosio, and completed in 1808.

The Louvre was still being added to by Napoleon III. The new wing of 1852–1857, by architects Louis Visconti and Hector Lefuel, represents the Second Empire's version of Neo-baroque, full of detail. The extensive sculptural program includes multiple pediments and a series of 86 statues of famous men, each one labelled. These include:

- historian Philippe de Commines, by Eugène-Louis Lequesne

- naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, by Eugène André Oudiné

- chemist Antoine Lavoisier, by Jacques-Léonard Maillet

- historian Jacques-Auguste de Thou, by Louis Auguste Deligand

- philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, by Jean-Baptiste Farochon

- Marquis de Vauban, by Gustave Crauck

In May 1871, during the suppression of the Paris Commune, the Tuileries Palace was set on fire by the Communards. The palace was entirely destroyed, with the exception of Pavilion de Flore. The Richelieu Library of the Louve was destroyed in the fire, but the rest of the museum was saved by the efforts of firemen and museum curators.[21] The western end of the Louvre courtyard has remained open since, forming the Cour d'honneur. Continued expansion and embellishment of the Louvre continued through 1876.

Grand Louvre and the Pyramids

The current Louvre Palace is an almost rectangular structure, composed of the square Cour Carrée and two wings which wrap the Cour Napoléon to the north and south. In the heart of the complex is the Louvre Pyramid, above the visitors' centre. The museum is divided into three wings: the Sully Wing to the east, which contains the Cour Carrée and the oldest parts of the Louvre; the Richelieu Wing to the north; and the Denon Wing, which borders the Seine to the south.

In 1983, French President François Mitterrand proposed the Grand Louvre plan to renovate the building and move the Finance Ministry out, allowing displays throughout the building. American architect I. M. Pei was awarded the project and proposed a modernist glass pyramid for the central courtyard. The pyramid and its underground lobby were inaugurated on 15 October 1988. Controversial at first, it has become an accepted Parisian architectural landmark. The second phase of the Grand Louvre plan, La Pyramide Inversée (The Inverted Pyramid), was completed in 1993. As of 2002, attendance had doubled since completion.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Sauval 1724, p. 9: "dans un vieux Glossaire Latin-Saxon, Leouar y est traduit Castellum".

- ↑ Briggs 2008, p. 116.

- ↑ Hanser 2006, p. 115; see also Wolfcatcher Royal; and Louveterie on the French Wikipédia.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ayers 2004, p. 32.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "The Louvre: One for the Ages". 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ayers 2004, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Ayers 2004, p. 33.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "The History of the Louvre: From Château to Museum". 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ↑ Hanser 2006, p. 115.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ballon 1991, p. 15.

- ↑ Hanser 2006, p. 115; Ayers 2004, p. 33.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Mignot, pp. 34, 35

- ↑ Sturdy, p. 42

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Blunt, p. 47

- ↑ Chaundy, Bob (29 September 2006). "Faces of the Week". BBC. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ↑ "Palais du Louvre". 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Mignot, p. 39

- ↑ Baedeker, pp. 87-89

- ↑ Edwards, p. 198

- ↑ Clerkin, Paul (22008). "Palais du Louvre, Paris". Archiseek.com. Retrieved 29 September 2008. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Héron de Villefosse, René, Histoire de Paris, Bernard Grasset, 1959.

- ↑ "Online Extra: Q&A with the Louvre's Henri Loyrette". Business Week Online. 17 June 2002. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

References

- Ayers, Andrew (2004). The Architecture of Paris. Stuttgart; London: Edition Axel Menges. ISBN 9783930698967.

- Baedeker, Karl (1891). Paris and Environs: With Routes from London to Paris; Handbook for Travellers. K. Baedeker.

- Ballon, Hilary (1991). The Paris of Henri IV: Architecture and Urbanism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-02309-2.

- Blunt, Anthony; Beresford, Richard (1999). Art and architecture in France, 1500-1700. New Haven Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07748-3. OCLC 237357512.

- Briggs, Keith (2008). "The Domesday Book castle LVVRE". Journal of the English Place-Name Society, vol. 40, pp. 113–118. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Edwards, Henry Sutherland (1893). Old and New Paris: Its History, Its People, and Its Places. Paris: Cassell. View at Google Books. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- Hanser, David A. (2006). Architecture of France. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313319020.

- Mesqui, Jean (1997). Chateaux-forts et fortifications en France. Paris: Flammarion. p. 493 pp. ISBN 2-08-012271-1.

- Mignot, Claude (1999). The Pocket Louvre: A Visitor's Guide to 500 Works. New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 0789205785.

- Pitt, Leonard. Walks Through Lost Paris: A Journey Into the Heart of Historic Paris. Shoemaker & Hoard. ISBN 978-1-59376-103-5. OCLC 224054099.

- Sauval, Henri (1724). Histoire et recherches des antiquités de la ville de Paris, vol. 2, Paris: C. Moette and J. Chardon. Copy at Google Books.

- Sturdy, David (1995). Science and social status: the members of the Académie des sciences 1666-1750. Woodbridge, Suffolk, U.K.: Boydell Press. ISBN 085115395X. Preview at Google Books.

Photo gallery

-

The Louvre Pyramid in the Cour Napoleon looking east.

-

Remains of the medieval foundations can still be seen underneath the museum.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palais du Louvre. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sculpted decoration of the Louvre. |

- Ministry of Culture database entry for the Louvre (French)

- Ministry of Culture photos

- A virtual visit of the Louvre

- Panoramic view of the pyramid and the Cour Napoléon

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||