Louis Dewis

| Louis Dewis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Isidore Louis Dewachter 1 November 1872 Mons, Belgium |

| Died |

5 December 1946 (aged 74) Biarritz, France |

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work |

L’innondation, 1920 |

| Awards |

Officier d'Académie now known as the Ordre des Palmes Académiques[1] Lauréat du Salon des Artistes Français Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur Grande Médaille de la Reconnaissance française Chevalier de l'Ordre de Leopold II Medaille du Roi Albert[2] San'f al-Talet (Officer - Order of Glory[3] (Tunisia) |

| Patron(s) | Georges Petit |

Louis Dewis (1872–1946) was a Belgian Post-Impressionist painter, who lived most of his adult life in France.[4]

Early life

Dewis was born Isidore Louis Dewachter in Mons, Belgium, the son of Isidore Louis Dewachter and Eloise Desmaret Dewachter. He spent his formative years in Liege where his closest boyhood friend was Richard Heintz (fr:Richard Heintz) (1871–1929),[5] who also became an internationally known landscape artist.

Although the name "Dewachter" may have Flemish roots, Dewachter always considered himself a Walloon.

Parental disapproval and burdensome responsibilities

Louis' successful merchant father was embarrassed that his son would waste his time with something as useless as painting. In a vain attempt to break his young son of this "bad habit," the elder Dewachter would, on occasion, throw away the boy’s canvases, paints and brushes.

Young Louis' love of art could not be deterred. It could, however, be overwhelmed by business and family responsibilities

As the eldest son, Louis was expected to take over the family business, a chain of men's clothing stores called Maison Dewachter. This was a duty that his father would not allow him to shirk. Dewis would come to manage the store in Bordeaux but there were Maison Dewachters in cities across France and Belgium, usually run locally by one cousin or another. Louis would bear this responsibility until after his father's death and the conclusion of World War I.

When his younger brother lost a small fortune gambling, it fell to Louis to make good on the enormous debt. This would take him several years.

Sunday painter

Through these travails, Louis Dewachter maintained an atelier in his home and was essentially a Sunday painter.

He signed his works “Louis Dewis” (pronounced Lew-WEE Dew-WEES), because his father refused to allow him to sully the family name by associating it with such a frivolous undertaking.

Because he didn't need the money — and because of his father's opposition — Dewis did not promote his art in his young adulthood.

Family

Louis Dewachter married Elisabeth Florigni (1873 - 25 August 1952).

Elisabeth was a Bordeaux socialite and the daughter of Joseph Jules Florigni (1842 - 14 April 1919) and Rose Lesfargues Palmyre Florigni (1843 - 11 September 1917).

Jules Florigni was the publisher of the Bordeaux regional newspaper, La Petite Gironde and Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur.

There was a feeling among some members of the Florigni family, which traced its roots back to the court of Catherine de' Medici, that "Babeth" had "married down."

In 1919, Dewis' older daughter, Yvonne Marie (1898 - 1966 in St. Petersburg, Florida), married Bradbury Robinson (1884–1949), a widowed American army officer and medical doctor who had remained in Europe after World War I to study medical techniques and to work for the United States Public Health Service. Robinson was already famous in the United States for having thrown, in 1906, the first forward pass in an American football game. In 1926 the couple moved to the United States. The Robinsons had seven children together, and she also gained a stepson from her husband's first marriage (his first wife having died in 1914).

In her memoirs, Yvonne remembers that in the early years of Dewis' career, her mother regarded her father's painting with benign indifference. She writes that Elisabeth Dewachter was pleased with her husband's choice of "hobbies" in one sense, telling her friends, "at least it's not noisy."

As the years passed, Elisabeth took more interest. It was she who maintained Dewis' scrapbook of critical reviews for three decades.

His younger daughter and only other child, Andrée Marguerite Elisabeth (24 September 1903 - 11 May 2002 in Paris), married businessman Charles Jérôme Ottoz, who proved to be less than supportive of his talented father-in-law.

A serious student of art, Andrée was passionate in her admiration of her father's work. She was so emotionally involved in his painting that one day Dewis wondered aloud whether his daughter would have loved him as much, "if I'd been a grocer." Years later, Andrée tearfully recalled assuring her father that she would.

Finally, a career begins

Dewis began to exhibit about 1916, shortly after his father's death. He was 44 years old.

In 1917, he helped organize Le Salon franco-belge in the Bordeaux Public Garden.[6] It was a charity event for the benefit of Belgian war refugees sponsored by the Belgian Benevolent Society of the South West and the Girondin Artists. It was at this exhibition that the art of Louis Dewis would first draw serious attention from some prominent art critics of the era.

Early reviews noted Dewis' "warm and harmonious" use of color and his "marvelous play of light and the most entrancing symphonies."

From this period until his death in Biarritz in 1946, Dewis' landscapes were shown regularly at major exhibitions across western Europe. They attracted favorable reviews in the international press, purchases from major museums and the highest decorations from the governments of three countries. However, the highest achievement of fame eluded him.

True, Dewis had finally escaped the dictates of his overbearing father that had stymied his career for almost three decades. He was now free to focus on painting. He could spend more time in the studio in his family's large apartment at 36 Rue de St-Cathérine over the Maison Dewachter in Bordeaux. But, his career would be marked by uncommon misfortune. As his daughter, Andrée, would say many years later, "Dad had hard luck!"

George Petit

The opportunity of a lifetime

The influential French art dealer, Georges Petit, was impressed by the Belgian's work in Bordeaux. He said of Dewis, "oh, he's a gentle one."

Petit's support could be life-changing. Here was a man who had attained the highest degree of success and influence in his profession. Petit's historic Expositions internationales de Peinture had featured works by Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley and James McNeill Whistler.

Petit scolded Dewis that he was wasting his life "selling clothes." He urged Dewis to sell his interest in Maison Dewachter and move his family from Bordeaux to Paris. The renowned dealer and owner of Galerie Georges Petit[7] told him, "come paint for me in Paris and I will make you famous."

Disaster

Dewis relented. He sold his business and relocated to Paris. But, within months of his arrival, Georges Petit was dead at the age of 64.

Dewis was on his own... and he was no self-promoter.

Painting for himself

In turning his career over to Petit, Dewis had taken the biggest risk of his life and lost.

He found himself in Paris without a sponsor. He, of course, had resources from the sale of his business. So, he rented an atelier and began painting for public exhibition.

From the beginning in Paris, Dewis' work was highly regarded and well reviewed, but it was never heavily promoted.

He had decided that Petit's legendary prowess as a marchand d'art was the perfect complement to his own talents. But, now totally independent, Dewis simply did not have the drive—or the desire—to achieve commercial success.

And, at this juncture of his life, Dewis was to encounter another antagonist. Dewis' son-in-law, Jérôme Ottoz, was a highly successful businessman who resented his talented and (gallingly) more famous beau-père. Ottoz (also Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur) dominated the timid artist... at one point talking Dewis out of accepting a lucrative offer of sponsorship by another Parisian art dealer.

Eventually, Dewis reconciled himself to his fate. And, happily so. He was perfectly content painting what he wanted to paint... and not producing what was in fashion or what art promoters thought would "sell."

He told his family, "I paint as the bird sings" — for the pure joy of expressing his emotions.

The 1920s and '30s

Dewis exhibited throughout France and Belgium in 1920s and 30s, as well as in Germany, Switzerland and Tunisia, then a French colony. Collectors and museums from Europe, South America and Japan purchased his work.[8]

He was named Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur.[8]

His art was honored in Paris' Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (1937).[8]

Dewis was a Lauréat of the Société des Artistes Français, an associate member of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, a founding member of the Nouveau Salon and of the Société des Peintres du Paris Moderne and of the Société Royale des Beaux-Arts of Belgium, among others.[8]

Dewis and his family fled Paris for the South West shortly before the Nazi occupation of 1940, initially staying with relatives in Bayonne.

Final years at Biarritz

By great good fortune in this time of war, they heard of a villa that was becoming available in Biarritz. An American was heading back to the United States and selling a large house with lovely gardens that he had named for his wife: Villa Pat. The family purchased the home and it was here that Dewis would paint for the last seven years of his life.

Biarritz wasn't far from Bordeaux, where Dewis had lived for more than 30 years from the 1880s up to the late 1910s.

He was once again inspired by the countryside of the Pays Basque.

Since travel was greatly limited during the occupation, Dewis often found his subjects within his own garden, in nearby parks and along the Atlantic coast.

Louis Dewis died of cancer at Villa Pat in late 1946.

He was buried in the family tomb at Bordeaux's Cimetière de la Chartreuse .[9]

A legacy in hibernation

Dewis' devoted daughter Andrée had returned to live in her Paris co-propriété (condominium) after the war ended. Except for the period of occupation, the flat in 17th arrondissement of Paris was her home from 1935 until her death in 2002. The spacious apartment, just a few blocks from the Parc Monceau, occupied the entire top floor of a 19th-century building.

Andrée had made many extended visits to Biarritz during her father's illness. After he died, she was intent on preserving everything related to his artistic career. She carefully crated up the entire contents of his atelier at the Villa Pat. Since she would be staying with her widowed mother in Biarritz for a while, she shipped the crates to Paris for safekeeping in the temporary custody of two trusted nephews, the noted architects Édouard Niermans (1903–1984) and Jean Niermans (1897-1989) (Jean Niermans ).[10] Their father, Édouard-Jean Niermans (fr:Édouard-Jean Niermans) (1859–1928),[11] the so-called architect of the "Café Society", married Dewis' sister, Louise Marie Héloïse Dewachter (1871-1963), in 1895. At his sister's home, Dewis had socialized with the likes of Auguste Renoir, Théo Van Gogh and Jules Cheret.[12]

Eventually, the boxes would be transferred to the attic of her co-propriété and placed in a locked room that was originally designed as maid's quarters. There the sturdy wooden boxes would sit, untouched, for nearly 50 years.

Dewis rediscovered

Dewis’ art had survived and blossomed despite the opposition of his father, the devastating loss of Petit, an antagonistic son-in-law and two world wars.

But now, it was all locked away and collecting dust. Jérôme had absolutely no interest in any effort to construct a legacy for his deceased rival.

As the years passed, Andrée had all but given up hope that her beloved father might be remembered.

By the mid-1990s, Jérôme was dead. Through a chance conversation with a visiting great nephew from the States (a grandson of her sister Yvonne), the then 92-year-old Andrée and the young American opened the crates and immediately resolved to return Dewis' work to the public.

The more than 400 paintings and hundreds of sketches that they found were catalogued. Experts were retained to evaluate the vast collection and what were judged to be the most outstanding pieces were cleaned and properly framed for public exhibition.

The effort culminated in the exhibition Dewis Rediscovered at the Courthouse Galleries[13] in Portsmouth, Virginia in 1998. It was the first public showing of Dewis' art in more than half a century.

Linda McGreevy[14][15] wrote essays for the catalogues for the first two Dewis exhibits in America. McGreevy, a Professor of Art History and Criticism and the Chair of the Art Department at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, has a special interest in French art between the two world wars. She described how Dewis' art was rediscovered in the attic of the Paris flat of Dewis/Dewachter's daughter:

"On the walls of the apartment in which she'd lived for over fifty years were works not only by her father but by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. During the course of this visit, and others over the next several months, [Andrée] recalled that there were probably more of her father's work stored in the attic, though she figured they'd probably all rotted away inasmuch as they'd been there since his death in 1946. What they found were... crates that, while caked in dust, the paintings themselves were in remarkably good condition. And stored in the ceiling were still more rolled canvases, numerous sketchbooks, journals, even his palette.

"Louis Dewis was hardly an unknown artist in his time, but then again, he was no Monet or Degas either (both of whom he knew intimately). Louis Dewis' work resembles most closely that of Corot, who was his strongest influence, except that it tends to borrow from the Impressionists a more resplendent use of color. Dewis painted mostly landscapes, those of the Belgian towns and countryside he knew all his life. But by the end of WW II, the popular art styles of the time had not only changed drastically but the art world he'd known had fled Paris entirely. When he died, it was as if he took his life's work with him, except for less than a dozen examples in family hands in this country, and the few on the walls of his daughter's apartment in Paris. However, thanks to the perseverance of [Dewis' American great-grandson] and... the Portsmouth Art Museum, the work of Louis Dewis, and perhaps his spirit too, have returned from the dead..."[16]

Since their rediscovery in 1995, more than 100 of Dewis' paintings found in his daughter's attic have been cleaned and framed and are lent to museums for the public to enjoy.

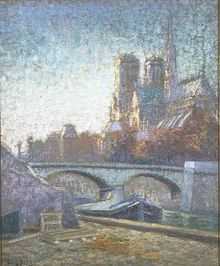

Gallery

-

Self Portrait, c. 1940

-

Bridge at St. Jean Pied de Port, 1940

-

The Village Church, 1945

Sources

- Catalogues for Dewis Rediscovered (1998) and Encore: Dewis Rediscovered (2002), Courthouse Galleries, Portsmouth, Virginia

- L'avenir de la Dordogne (Périgueux, France), 5 January 1918

- La Petite Gironde (Bordeaux, France), 11 June 1918

- Memoirs of Yvonne Dewachter Robinson Young

- Transcribed interviews with Andrée Dewachter Ottoz (1995–2000)

- louisdewis.com

- YouTube Video of "Dewis Rediscovered" Exhibition at Portsmouth, Virginia in 1998

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Louis Dewis. |

- ↑ Ordre des Palmes Académiques

- ↑ "Medaille du Roi Albert".

- ↑ "Nishan al-Iftikhar, San'f al-Talet".

- ↑ "Official Louis Dewis Website".

- ↑ Wallonie-en-Ligne on Richard Heintz (in French)

- ↑ "Railbookers on Bordeaux Public Garden". Railbookers.

- ↑ National Gallery of Art on Georges Petit

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Obituary of Louis Dewachter, Journal de Biarritz (Biarritz, France), 17 December 1946

- ↑ "Cimetière de la Chartreuse". eventseeker.

- ↑ Archiwebture: Niermans, Jean (1897-1989) and Edouard (1904-1984) and the agency of the Brothers Niermans (in French)

- ↑ Archiwebture: Niermans, Edouard-Jean (1859-1928) (in French)

- ↑ "Montlaur: An Historic Castle in Languedoc".

- ↑ "Courthouse Galleries Website, Portsmouth, Virginia".

- ↑ Old Dominion University Curriculum Vitae of Linda McGreevy, Ph.D.

- ↑ Old Dominion University Webpage for Linda McGreevy, Ph.D.

- ↑ Catalogue for Dewis Rediscovered (1998), Courthouse Galleries, Portsmouth, Virginia