Lost comet

A lost comet is a previously discovered comet that has been missed at its most recent perihelion passage, generally because there is not enough data to calculate reliably the comet's orbit and predict its location.

Lost comets can be compared to lost asteroids, although calculation of cometary orbits differs because of nongravitational forces that can affect comets, such as emission of jets of gas from the nucleus. Some astronomers have specialized in this area, such as Brian G. Marsden who successfully predicted the 1992 return of the once-lost periodic comet Swift–Tuttle.

Reasons for loss

There are a number of reasons why a comet might be missed by astronomers during subsequent apparitions. Firstly, cometary orbits may be perturbed by interaction with the giant planets, such as Jupiter. This, along with nongravitational forces, can result in changes to the date of perihelion. Alternatively, it is possible that the interaction of the planets with a comet can move its orbit too far from the Earth to be seen or even eject it from the Solar System, as is believed to have happened in the case of Lexell's Comet. As some comets periodically undergo "outbursts" or flares in brightness, it may be possible for an intrinsically faint comet to be discovered during an outburst and subsequently lost.

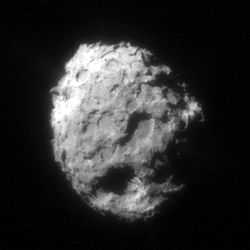

Comets can also run out of volatiles. Eventually most of the volatile material contained in a comet nucleus evaporates away, and the comet becomes a small, dark, inert lump of rock or rubble,[1] an extinct comet that can resemble an asteroid (see also Comets#Fate of comets). This may have occurred in the case of 5D/Brorsen, which was considered by Marsden to have probably "faded out of existence" in the late 19th century.[2]

Comets are in some cases known to have disintegrated during their perihelion passage, or at other points during their orbit. The best-known example is Biela's Comet, which was observed to split into two components before disappearing after its 1852 apparition. In modern times 73P/Schwassmann–Wachmann has been observed in the process of breaking up.

Occasionally, the discovery of an object turns out to be a rediscovery of a previously lost object, which can be determined by calculating its orbit and matching calculated positions with the previously recorded positions. In the case of lost comets this is especially tricky. For example, the comet 177P/Barnard (also P/2006 M3), discovered by Edward Emerson Barnard on June 24, 1889, was rediscovered after 116 years in 2006.[3] On July 19, 2006, 177P came within 0.36 AU of the Earth.[4]

Comets can be gone but not considered lost, even though they may not be expected back for hundreds or even thousands of years. With more powerful telescopes it has become possible to observe comets for longer periods of time after perihelion. For example, Comet Hale–Bopp was observable with the naked eye about 18 months after its approach in 1997.[5] It is expected to remain observable with large telescopes until perhaps 2020, by which time it will be nearing 30th magnitude.[6]

Comets that have been lost or which have disappeared have names beginning with a "D" according to current IAU conventions.

Table

Comets are typically observed on a periodic return. When they do not they are sometimes found again, while other times they may break up into fragments. These fragments can sometimes be further observed, but the comet is no longer expected to return. Other times a comet will not be considered lost until it does not appear at a predicted time. Comets may also collide with another object, such as Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9, which collided with Jupiter in 1994.

| Name(s) | Initially discovered | Recovered or lost | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 34D/Gale | 1927 | 1938 | Lost since 1938 |

| 206P/Barnard–Boattini | 1892 | 2008 | Found since 2008 |

| 15P/Finlay | 1886–1926 | 1953 | Found since 1953 |

| 107P/Wilson–Harrington | 1949 | 1992 | Found since 1992 |

| 73P/Schwassmann–Wachmann | 1930 | ? | Breakup (1995) |

| 25D/Neujmin | 1916 | Considered lost since 1927 | |

| 69P/Taylor | 1915 | 1976, 1984, 1990, 1998 | |

| 11P/Tempel–Swift–LINEAR | 1908 | 2001 | Found since 2001 |

| 113P/Spitaler | 1897 | 1993 | Found since 1994 |

| 205P/Giacobini (D/1896 R2) | 1896 | 2008 | |

| 18D/Perrine–Mrkos | 1896 | 1955 | Lost |

| 17P/Holmes | 1892–1906 | 1964 | Found Since 1964 |

| 177P/Barnard | 1889 | 2006 | Recovered after 116 years[3] |

| 20D/Westphal | 1852 | 1913 | Lost |

| 5D/Brorsen | 1846 | 1857, 1868, 1879 | Lost since 1879 |

| 54P/de Vico–Swift–NEAT | 1844 | 1894, 1965, 2002 | Found since 2002 |

| 27P/Crommelin | 1818 | 1873, 1928 | Found since 1928 |

| 3D/Biela | 1772 | 1852 | Broke up (1846), Andromedids |

| D/1770 L1 (Lexell) | 1770 | Lost since 1770 | |

See also

- List of periodic comets

- List of non-periodic comets

- Lost asteroids

- Brian G. Marsden, comet orbit expert

- The Lost Comet (1964), book by Stanton A. Coblentz

References

- ↑ "If comets melt, why do they seem to last for long periods of time?", Scientific American, November 16, 1998

- ↑ Kronk, G. W.5D/Brorsen, Cometography.com

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Naoyuki Kurita. "Comet Barnard 2 on Aug 4, 2006". Stellar Scenes. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ↑ "177P/Barnard". Kazuo Kinoshita. 2006-11-18. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ Kidger, M.R.; Hurst, G; James, N. (2004). "The Visual Light Curve Of C/1995 O1 (Hale–Bopp) From Discovery To Late 1997". Earth, Moon, and Planets 78 (1–3): 169–177. Bibcode:1997EM&P...78..169K. doi:10.1023/A:1006228113533.

- ↑ West, Richard M. (February 7, 1997). "Comet Hale–Bopp (February 7, 1997)". European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||