Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause is a regional American cultural movement, based in the white South, seeking to reconcile the traditionalist white society of the antebellum South that they admire, to the defeat of the Confederate States of America in the American Civil War of 1861–1865.[1] It forms an important minority viewpoint among the ways to commemorate the war. The United Daughters of the Confederacy is a major organization that has propounded the Lost Cause for over a century.

Supporters typically portray the Confederacy's cause as noble and most of its leaders as exemplars of old-fashioned chivalry, defeated by the Union armies through numerical and industrial force that overwhelmed the South's superior military skill and courage. Proponents of the Lost Cause movement also condemned the Reconstruction that followed the Civil War, claiming that it had been a deliberate attempt by Northern politicians and speculators to destroy the traditional Southern way of life. In recent decades Lost Cause themes have been widely promoted by the Neo-Confederate movement in books and op-eds and especially in one of the movement's magazines the Southern Partisan.

History

Many white Southerners were devastated economically, emotionally, and psychologically by the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865. Before the war, many Southerners proudly felt that their rich military tradition and superior dedication to the concept of honor would enable them to prevail in the conflict. When this did not happen, white Southerners sought consolation in attributing their loss to factors beyond their control, such as physical size and overwhelming brute force.[2]

The term Lost Cause first appeared in the title of an 1866 book by the historian Edward A. Pollard, The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates.[3] However, it was the articles written by Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early in the 1870s for the Southern Historical Society that firmly established the Lost Cause as a long-lasting literary and cultural phenomenon. The 1881 publication of The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government by Jefferson Davis, a two volume defense of the Southern cause as Davis saw it, provided another important text in the history of the Lost Cause. Even though the book's initial sales were very disappointing to the author, the book remained in print and was often used to justify the Southern position and to distance it from slavery.

Early's original inspiration for his views may have come from General Robert E. Lee. When Lee published his farewell order to the Army of Northern Virginia, he consoled his soldiers by speaking of the "overwhelming resources and numbers" that the Confederate army fought against. In a letter to Early, Lee requested information about enemy strengths from May 1864 to April 1865, the period in which his army was engaged against Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (the Overland Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg). Lee wrote, "My only object is to transmit, if possible, the truth to posterity, and do justice to our brave Soldiers."[4] In another letter, Lee wanted all "statistics as regards numbers, destruction of private property by the Federal troops, &c." because he intended to demonstrate the discrepancy in strength between the two armies and believed it would "be difficult to get the world to understand the odds against which we fought." Referring to newspaper accounts that accused him of culpability in the loss, he wrote, "I have not thought proper to notice, or even to correct misrepresentations of my words & acts. We shall have to be patient, & suffer for awhile at least. ... At present the public mind is not prepared to receive the truth."[4] All of these were themes made prominent by Early and the Lost Cause writers in the nineteenth century and that continued to be important throughout the twentieth.[5]

Memorial associations such as the United Confederate Veterans, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and Ladies Memorial Associations integrated Lost Cause themes to help Southerners cope with the many changes during this era, most significantly Reconstruction.[6][7] These institutions have lasted to the present time period and descendants of Southern soldiers continue to attend these meetings. However, these groups are now more geared towards honoring the memory and sacrifices of Confederate soldiers than the continuation of the old Southern ways.[8]

New South

Historians have emphasized how the "Lost Cause" theme helped white Southerners adjust to their new status and move forward into what was called "the New South." Hillyer argues that the Confederate Memorial Literary Society (CMLS), founded by elite white women in Richmond, Virginia, in the 1890s, exemplifies this solution. The CMLS founded the Confederate Museum to document and defend the Confederate cause and to recall the antebellum mores that the new South's business ethos was displacing. By focusing on military sacrifice, rather than grievances regarding the North, the Confederate Museum aided the process of sectional reconciliation according to Hillyer. By depicting slavery as benevolent, the museum's exhibits reinforced the notion that Jim Crow was a proper solution to racial tensions that had escalated during Reconstruction. Lastly by glorifying the common soldier and portraying the South as "solid," the museum promoted acceptance of industrial capitalism. Thus, the Confederate Museum both critiqued and eased the economic transformations of the New South, and enabled Richmond to reconcile its memory of the past with its hopes for the future, leaving the past behind as it developed new industrial and financial roles.[9]

Religious revivals

Wilson argues that many white Southerners felt that defeat in the war was God's punishment for their sins, and turned increasingly to religion as their solace. The postwar era saw the birth of a pervasive "civil religion that was heavy with mythology, ritual, and organization. White southerners tried to defend on a cultural and religious level what defeat in 1865 made impossible on a political level. The Lost Cause – defeat in a holy war – left southerners to face guilt, doubt, and the triumph of evil: that is, they formed what C. Vann Woodward has called a uniquely Southern sense of the tragedy of history."[10]

Poole argues that in fighting to defeat the Republican reconstruction government in South Carolina in 1876, white Democrats portrayed the Lost Cause scenario through "Hampton Days" celebrations shouting "Hampton or Hell!". They staged the contest between Wade Hampton and incumbent governor Daniel H. Chamberlain as a religious struggle between good and evil, and calling for "redemption."[11] Indeed, throughout the South the conservatives who overthrew Reconstruction were often called "Redeemers," echoing Christian theology.[12]

Tenets

| “ | (WHF Lee) objected to the phrase too often used—South as well as North—that the Confederates fought for what they thought was right. They fought for what they knew was right. They, like the Greeks, fought for home, the graves of their sires, and their native land. | ” |

| —New York Times, | ||

| “ | [The] servile instincts [of slaves] rendered them contented with their lot, and their patient toil blessed the land of their abode with unmeasured riches. Their strong local and personal attachment secured faithful service ... never was there happier dependence of labor and capital on each other. The tempter came, like the serpent of Eden, and decoyed them with the magic word of 'freedom' ... He put arms in their hands, and trained their humble but emotional natures to deeds of violence and bloodshed, and sent them out to devastate their benefactors. | ” |

| —Confederate President Jefferson Davis | ||

Some of the main tenets of the Lost Cause movement were that:

- Confederate generals such as Lee, Albert Sidney Johnston and Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson represented the virtues of Southern nobility and fought bravely and fairly. On the other hand, most Northern generals were characterized as possessing low moral standards, because they subjected the Southern civilian population to indignities like Sherman's March to the Sea and Philip Sheridan's burning of the Shenandoah Valley in the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Union General Ulysses S. Grant is often portrayed as an alcoholic.

- Losses on the battlefield were inevitable due to Northern superiority in resources and manpower.

- Battlefield losses were also the result of betrayal and incompetence on the part of certain subordinates of General Lee, such as General James Longstreet, who was reviled for doubting Lee at Gettysburg, and George Pickett, who led the disastrous Pickett's Charge that broke the South's back (the Lost Cause focused mainly on Lee and the eastern theater of operations, and often cited Gettysburg as the main turning point of the war).

- Defense of states' rights, rather than preservation of chattel slavery, was the primary cause that led eleven Southern states to secede from the Union, thus precipitating the war.

- Secession was a justifiable constitutional response to Northern cultural and economic aggressions against the Southern way of life.

- Slavery was a benign institution, and the slaves were loyal and faithful to their benevolent masters.[14]

The most powerful images and symbols of the Lost Cause were Robert E. Lee, Albert Sidney Johnston and Pickett's Charge. David Ulbrich wrote, "Already revered during the war, Robert E. Lee acquired a divine mystique within Southern culture after it. Remembered as a leader whose soldiers would loyally follow him into every fight no matter how desperate, Lee emerged from the conflict to become an icon of the Lost Cause and the ideal of the antebellum Southern gentleman, an honorable and pious man who selflessly served Virginia and the Confederacy. Lee's tactical brilliance at Second Bull Run and Chancellorsville took on legendary status, and despite his accepting full responsibility for the defeat at Gettysburg, Lee remained largely infallible for Southerners and was spared criticism even from historians until recent times." Victor Davis Hansen points out that Albert Sidney Johnston was the first officer to be appointed a full general by Jefferson Davis and to lead Confederate forces in the Western Theater. His death during the first day of the battle at Shiloh arguably led to the Confederacy's defeat in that conflict.[6]

In terms of Lee's subordinates, the key villain in Jubal Early's view was Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. Despite the fact that General Lee took all responsibility for defeats,(in particular Gettysburg) Early's writings place the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg squarely on Longstreet's shoulders, accusing him of failing to attack early in the morning of July 2, 1863, as instructed by Lee. In fact, however, Lee never expressed dissatisfaction with the second-day actions of his "Old War Horse." Longstreet was widely disparaged by Southern veterans because of his post-war cooperation with President Ulysses S. Grant (with whom he had shared a close friendship before the war) and for joining the Republican Party. Grant, in rejecting the Lost Cause arguments, said in an 1878 interview that he rejected the notion that the South had simply been overwhelmed by numbers. Grant argued, "This is the way public opinion was made during the war and this is the way history is made now. We never overwhelmed the South ... What we won from the South we won by hard fighting." He further noted that when comparing resources the "4,000,000 of negroes" who "kept the farms, protected the families, supported the armies, and were really a reserve force" were not treated as a southern asset.[15]

Further adoption

Gallagher contends that Douglas Southall Freeman's definitive four-volume biography of Lee, published in 1934, "cemented in American letters an interpretation of Lee very close to Early's utterly heroic figure."[16] In this work, Lee's subordinates were primarily to blame for errors that lost battles. While Longstreet was the most common target of such attacks, others came under fire as well. Richard Ewell, Jubal Early, J. E. B. Stuart, A. P. Hill, George Pickett, and many others were frequently attacked and blamed by Southerners in an attempt to deflect criticism from Lee. (As mentioned above, Lee accepted total responsibility for his defeats and never blamed any of his subordinates.)

Hudson Strode wrote a widely-read scholarly three-volume biography of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. A leading scholarly journal reviewed it stressing Strode's political biases:

- "His [Jefferson Davis's] enemies are devils, and his friends, like Davis himself, have been canonized. Strode not only attempts to sanctify Davis but also the Confederate point of view, and this study should be relished by those vigorously sympathetic with the Lost Cause.[17]

Gone with the Wind

The Lost Cause view reached tens of millions of Americans in the best-selling 1936 novel Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell and the Oscar-winning 1939 film. Helen Taylor argues that:

- Gone with the Wind has almost certainly done its ideological work. It has sealed in popular imaginations a fascinated nostalgia for the glamorous southern plantation house and ordered hierarchical society in which slaves are 'family,' and there is a mystical bond between the landowner and the rich soil those slaves work for him. It has spoken eloquently-albeit from an elitist perspective-of the grand themes (war, love, death, conflicts of race, class, gender, and generation) that have crossed continents and cultures.[18]

Blight wrote:

- "From this combination of Lost Cause voices a reunited America arose pure, guiltless, and assured that the deep conflicts in its past had been imposed upon it by otherworldly forces. The side that lost was especially assured that its cause was true and good. One of the ideas the reconciliationist Lost Cause instilled deeply into the national culture is that even when Americans lose, they win. Such was the message, the indomitable spirit, that Margaret Mitchell infused into her character Scarlett O'Hara in Gone With the Wind ... ."[19]

Southerners were portrayed as noble, heroic figures, living in a doomed romantic society, who rejected the realistic advice offered by the Rhett Butler character and never understood the risk they were taking in going to war.

Birth of a Nation

Another prominent use of the Lost Cause perspective was in Thomas F. Dixon, Jr.'s 1905 novel The Clansman, later adapted to the screen by D. W. Griffith in his highly successful movie Birth of a Nation in 1915. Blight noting that Dixon and Griffith collaborated on Birth of a Nation argues:

- Dixon's vicious version of the idea that blacks had caused the Civil War by their very presence, and that Northern radicalism during Reconstruction failed to understand that freedom had ushered blacks as a race into barbarism, neatly framed the story of the rise of heroic vigilantism in the South. Reluctantly, Klansmen – white men – had to take the law into their own hands in order to save Southern white womanhood from the sexual brutality of black men. Dixon's vision captured the attitude of thousands and forged in story form a collective memory of how the war may have been lost but Reconstruction was won – by the South and a reconciled nation. Riding as masked cavalry, the Klan stopped corrupt government, prevented the anarchy of 'Negro rule,' and most of all, saved white supremacy.[20]

In both the book and the movie, the Ku Klux Klan is portrayed as continuing the noble traditions of the antebellum South and the heroic Confederate soldier by defending Southern culture in general and Southern womanhood in particular against rape and depredations at the hands of the Freedmen and Yankee carpetbaggers during Reconstruction.

Faulkner

In his novels about the Sartoris family, William Faulkner paid homage to the men who supported the Lost Cause ideal, while suggesting that the ideal itself was misguided and out of date.[21]

20th & 21st century usage

.svg.png)

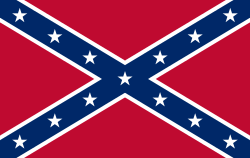

Basic assumptions of the Lost Cause have proved durable for many in the modern South. Lost Cause tenets are frequently voiced during controversies surrounding public display of the Confederate flags and various state flags. Historian John Coski noted that the Sons of Confederate Veterans, the "most visible, active, and effective defender of the flag", "carried forward into the twenty-first century, virtually unchanged, the Lost Cause historical interpretations and ideological vision formulated at the turn of the twentieth."[22] Coski wrote concerning "the flag wars of the late twentieth century": The flag most commonly associated with the Confederacy is the Army of Tennessee Confederate battle flag.

From the ... early 1950s, SCV officials defended the integrity of the battle flag against trivialization and against those who insisted that its display was unpatriotic or racist. SCV spokesmen reiterated the consistent argument that the South fought a legitimate war for independence, not a war to defend slavery, and that the ascendant "Yankee" view of history falsely vilified the South and led people to misinterpret the battle flag.[23]

The Confederate States of America used several flags during its existence from 1861 to 1865. Since the end of the American Civil War, personal and official use of Confederate flags, and of flags derived from these, has continued under considerable controversy. Currently the state flag of Mississippi and the flag of Georgia prior to 2001 include the Confederate battle flag.

Twenty-first century defenders realize that the flag is widely associated with slavery and racism but claim that just as flying the United States flag does not necessarily signify approval of the sins of the past, so public display of a banner they consider to still be a regional and cultural emblem should not be taken as support for old prejudices and institutions, but instead as a reclaimed symbol of the New South's culture and unique Southern heritage.

Contemporary historians are largely unsympathetic to arguments that secession was not motivated by slave ownership. There were numerous causes for secession, though to state that preserving slavery was not a factor is considered historically incorrect. The confusion may come from blending the causes of secession with the causes of the war – which are separate but related issues. (Lincoln did not enter a military conflict to free the slaves but to put down a rebellion.) Historian Kenneth M. Stampp claimed that each side supported states' rights or federal power only when it was convenient to do so.[24] Stampp also cited Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens' A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States as an example of a Southern leader who said that slavery was the "cornerstone of the Confederacy" when the war began and then said that the war was not about slavery but states' rights after Southern defeat. According to Stampp, Stephens became one of the most ardent defenders of the 'Lost Cause' theory.[25]

Similarly, historian William C. Davis explained the Confederate Constitution's protection of slavery at the national level as follows:

To the old Union they had said that the Federal power had no authority to interfere with slavery issues in a state. To their new nation they would declare that the state had no power to interfere with a federal protection of slavery. Of all the many testimonials to the fact that slavery, and not states rights, really lay at the heart of their movement, this was the most eloquent of all.[26]

Davis further notes that, "Causes and effects of the war have been manipulated and mythologized to suit political and social agendas, past and present."[27] Historian David Blight says that "its use of white supremacy as both means and ends" has been a key characteristic of the Lost Cause.[28] Historian Allan Nolan writes:

...the Lost Cause legacy to history is a caricature of the truth. The caricature wholly misrepresents and distorts the facts of the matter. Surely it is time to start again in our understanding of this decisive element of our past and to do so from the premises of history unadulterated by the distortions, falsehoods, and romantic sentimentality of the Myth of the Lost Cause.[29]

There are modern Lost Cause writers of history such as James Ronald Kennedy and his twin brother Walter Donald Kennedy (founders of The League of the South and author of The South Was Right! and Jefferson Davis Was Right!) who play down slavery as a cause in favor of Southern Nationalism. The Kennedys describe "the terrorist methods" and "heinous crimes" committed by the Union during the war and then in a chapter titled "The Yankee Campaign of Cultural Genocide" state that they will show "from the United States government's own official records that the primary motivating factor was a desire of those in power to punish and to exterminate the Southern nation and in many cases to procure the extermination of the Southern people."[30]

In arguing why the theme of this book is important to contemporary Southerners, the Kennedys write in the conclusion of their work:

The Southern people have all the power we need to put an end to forced busing, affirmative action, extravagant welfare spending, the punitive Southern-only Voting Rights Act, the refusal of the Northern liberals to allow Southern conservatives to sit on the Supreme Court, and the economic exploitation of the South into a secondary economic status. What is needed is not more power but the will to use the power at hand! The choice is now yours—ignore this challenge and remain a second-class citizen, or unite with your fellow Southerners and help start a Southern political revolution.[31]

Historian David Goldfield characterizes books "such as 'The South Was Right'" as:

...explaining that "the War of Northern Aggression was not fought to preserve any union of historic creation, formation, and understanding, but to achieve a new union by conquest and plunder." As for the abolitionists, they were a collection of socialists, atheists, and "reprehensible agitators."[32]

Historian William C. Davis labels many of the myths surrounding the war as "frivolous" and included attempts to rename the war by "Confederate partisans" which continue to this day. He claims names such as the War of Northern Aggression and the expression coined by Alexander Stephens, War Between the States, were just attempts to deny that the Civil War was an actual civil war.[33]

Historian A. Cash Koiniger has argued that Gary Gallagher has mischaracterized films that depict the Lost Cause. He writes, Gallagher:

- concedes that "Lost Cause themes" (with the important exception of minimizing the importance of slavery) are based on historical truths (p. 46). Confederate soldiers were often outnumbered, ragged and hungry, southern civilians did endure much material deprivation and a disproportionate amount of bereavement, U.S. forces did wreck havoc on southern infrastructure and private property and the like, yet whenever these points appear in films Gallagher considers them motifs "celebratory" of the Confederacy (p. 81).[34]

Even in the 21st century, the use of Confederate symbols continues to be controversial — a report in March 2015 details the efforts of the Sons of Confederate Veterans to require the State of Texas to issue a vanity license plate honoring their organization, against the state's wishes. The proposed vanity plate design would incorporate the SCV symbol, centered on a square-format Confederate battle flag designed by William Porcher Miles used originally by the Army of Northern Virginia during the Civil War. The case, Walker v. Texas Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans, was heard by the Supreme Court of the United States on March 23, 2015.[35]

See also

- Confederate Memorial Day

- Confederate Memorial Hall

- Confederate monuments

- League of the South

- Naming the American Civil War

- Neo-Confederate

- Solid South

- Sons of Confederate Veterans

- Southern Democrats

- States' rights

- Richard M. Weaver (1910-1963)

- United Confederate Veterans

- White nationalism

References

Notes

- ↑ Gallagher (2000) p. 1. Gallagher wrote:

The architects of the Lost Cause acted from various motives. They collectively sought to justify their own actions and allow themselves and other former Confederates to find something positive in all-encompassing failure. They also wanted to provide their children and future generations of white Southerners with a 'correct' narrative of the war.

- ↑ Gallagher (2000) p. 1

- ↑ Ulbrich, p. 1221.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gallagher, p. 12.

- ↑ Gallagher and Nolan p. 43.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ulbrich, p. 1222.

- ↑ Janney, p. 40.

- ↑ "United Daughters of the Confederacy". United Daughters of the Confederacy.

- ↑ Reiko Hillyer, "Relics of Reconciliation: The Confederate Museum and Civil War Memory in the New South," Public Historian, Nov 2011, Vol. 33 Issue 4, pp 35-62,

- ↑ Charles Reagan Wilson, "The Religion of the Lost Cause: Ritual and the Organization of the Southern Civil Religion, 1865-1920," Journal of Southern History, May 1980, Vol. 46 Issue 2, pp 219-238 in JSTOR

- ↑ W. Scott Poole, "Religion, Gender, and the Lost Cause in South Carolina's 1876 Governor's Race: 'Hampton or Hell!'," Journal of Southern History, Aug 2002, Vol. 68 Issue 3, pp 573-98

- ↑ Stephen E. Cresswell, Rednecks, redeemers, and race: Mississippi after Reconstruction (2006)

- ↑ Blight p. 260. Blight attributes the quote to the Da Capo edition of Davis' work, volume 2 pp. iv, 161–162.

- ↑ Gallagher and Nolan p. 16. Nolan writes, "Given the central role of African Americans in the sectional conflict, it is surely not surprising that Southern rationalizations have extended to characterizations of the persons of these people. In the legend there exist two prominent images of the black slaves. One is of the "faithful slave"; the other is what William Garrett Piston calls "the happy darky stereotype."

- ↑ Blight p. 93

- ↑ Gallagher, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ LeRoy H. Fischer in The Journal of American History September, 1965 p 396 in JSTOR

- ↑ Helen Taylor, "Gone with the Wind and Its Influence," pp 258-67 in Carolyn Perry and Mary Weaks-Baxter, eds. (2002). The History of Southern Women's Literature. LSU Press. p. 266.

- ↑ Blight p. 283-284.

- ↑ Blight p. 111.

- ↑ Blight pp. 292, 448–449

- ↑ Coski pp. 192–193

- ↑ Coski p. 193. Coski (p. 62) also wrote:

- "Just as the battle flag became during the war the most important emblem of Confederate nationalism, so did it become during the memorial period [the late 19th Century through the 1920s] the symbolic embodiment of the Lost Cause."

- ↑ Stampp, The Causes of the Civil War, page 59

- ↑ Stampp, The Causes of the Civil War, pages 63–65

- ↑ William C. Davis, Look Away, pages 97–98

- ↑ Davis, The Cause Lost p. x

- ↑ Blight p. 259

- ↑ Gallager and Nolan p. 29

- ↑ Kennedy and Kennedy p. 275-276

- ↑ Kennedy and Kennedy p. 309

- ↑ Goldfield p. 302

- ↑ Davis, The Cause Lost p. 178

- ↑ A. Cash Koiniger review of Gallagher, Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil War (2008), citing pages 46 and 81, in The Journal of Military History (Jan 2009) 73#1 p 286

- ↑ Millhiser, Ian (March 20, 2015). "Supreme Court to Decide if Texas Must Issue Confederate Flag License Plates". thinkprogress.org. ThinkProgress. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

Bibliography

- Bailey, Fred Arthur. "The Textbooks of the" Lost Cause": Censorship and the Creation of Southern State Histories." Georgia Historical Quarterly (1991): 507-533. in JSTOR

- Bailey, Fred Arthur. "Free Speech and the Lost Cause in the Old Dominion." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (1995): 237-266. in JSTOR

- Barnhart, Terry A. Albert Taylor Bledsoe: Defender of the Old South and Architect of the Lost Cause (Louisiana State University Press; 2011) 288 pages

- Blight, David W. (2001-02-09). Race and Reunion : The Civil War in American Memory. Belknap Press. ISBN 0-674-00332-2.

- Coski, John M. The Confederate Battle Flag. (2005) ISBN 0-674-01722-6

- Davis, William C. (1996). The Cause Lost: Myths and Realities of the Confederacy. (1st ed.). Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A.: Univ Pr of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0809-5.

- Davis, William C. Look Away: A History of the Confederate States of America. (2002) ISBN 0-684-86585-8

- Foster, Gaines M. (1988). Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause and the Emergence of the New South, 1865–1913. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505420-2.

- Freeman, Douglas Southall, The South to Posterity: An Introduction to the Writing of Confederate History (1939).

- Gallagher, Gary W. and Alan T. Nolan (ed.), The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History, Indiana University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-253-33822-0.

- Gallagher, Gary, Jubal A. Early, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History: A Persistent Legacy (Frank L. Klement Lectures, No. 4), Marquette University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-87462-328-6.

- Goldfield, David. Still Fighting the Civil War. (2002) ISBN 0-8071-2758-2

- Janney, Caroline E. (2008). Burying the dead but not the past: Ladies' Memorial Associations and the lost cause. U of North Carolina P. ISBN 978-0-8078-3176-2. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- Kennedy, James Ronald and Kennedy, Walter Donald. The South Was Right! (1994) ISBN 1-56554-024-7

- Reardon, Carol, Pickett's Charge in History and Memory, University of North Carolina Press, 1997, ISBN 0-8078-2379-1.

- Stampp, Kenneth. The Causes of the Civil War. (3rd edition 1991)

- Ulbrich, David, "Lost Cause", Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Wilson, Charles Reagan, Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865–1920, University of Georgia Press, 1980, ISBN 0-8203-0681-9.

- Wilson, Charles Reagan, "The Lost Cause Myth in the New South Era" in Myth America: A Historical Anthology, Volume II. 1997. Gerster, Patrick, and Cords, Nicholas. (editors.) Brandywine Press, St. James, NY. ISBN 1-881089-97-5

External links

- The Lost Cause in Encyclopedia Virginia

- Ladies' Memorial Associations in Encyclopedia Virginia

- United Daughters of the Confederacy in Encyclopedia Virginia

- Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly (June 15, 2009). "Southern Memory, Southern Monuments, and the Subversive Black Mammy". Southern Spaces.