Loopholes in Bell test experiments

In Bell test experiments, there may be problems of experimental design or set-up that affect the validity of the experimental findings. These problems are often referred to as "loopholes". See the article on Bell's theorem for the theoretical background to these experimental efforts (see also J.S. Bell). The purpose of the experiment is to test whether nature is best described using a local hidden variable theory or by the quantum entanglement theory of quantum mechanics.

The "detection efficiency", or "fair sampling" problem is the most prevalent loophole in optical experiments. Another loophole that has more often been addressed is that of communication, i.e. locality. There is also the "disjoint measurement" loophole which entails multiple samples used to obtain correlations as compared to "joint measurement" where a single sample is used to obtain all correlations used in an inequality. To date, no test has simultaneously closed all loopholes.

In some experiments there may be additional defects that make "local realist" explanations of Bell test violations possible;[1][2] these are briefly described below.

Many modern experiments are directed at detecting quantum entanglement rather than ruling out local hidden variable theories, and these tasks are different since the former accepts quantum mechanics at the outset (no entanglement without quantum mechanics). This is regularly done using Bell's theorem, but in this situation the theorem is used as an entanglement witness, a dividing line between entangled quantum states and separable quantum states, and is as such not as sensitive to the problems described here.

Loopholes

Detection efficiency, or fair sampling

In Bell test experiments, one problem is that detection efficiency may be less than 100%, and this is always the case in optical experiments. This problem was noted first by Pearle in 1970,[3] and Clauser and Horne (1974) devised another result intended to take care of this. Some results were also obtained in the 1980s but the subject has undergone significant research in recent years. The many experiments affected by this problem deal with it, without exception, by using the "fair sampling" assumption (see below).

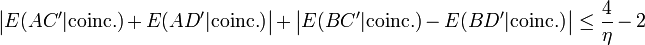

This loophole changes the inequalities to be used; for example the CHSH inequality:

is changed. When data from an experiment is used in the inequality one needs to condition on that a "coincidence" occurred, that a detection occurred in both wings of the experiment. This will change the inequality into

In this formula, the  denotes the efficiency of the experiment, formally the minimum probability of a coincidence given a detection on one side.[4][5] In Quantum mechanics, the left-hand side reaches

denotes the efficiency of the experiment, formally the minimum probability of a coincidence given a detection on one side.[4][5] In Quantum mechanics, the left-hand side reaches  , which is greater than two, but for a non-100% efficiency the latter formula has a larger right-hand side. And at low efficiency (below

, which is greater than two, but for a non-100% efficiency the latter formula has a larger right-hand side. And at low efficiency (below  ≈83%), the inequality is no longer violated.

≈83%), the inequality is no longer violated.

All optical experiments are affected by this problem, having typical efficiencies around 5-30%. Several non-optical systems such as trapped ions,[6] superconducting qubits[7] and NV centers[8] have been able to bypass the detection loophole. Unfortunately, they are all still vulnerable to the communication loophole.

There are tests that are not sensitive to this problem, such as the Clauser-Horne test, but these have the same performance as the latter of the two inequalities above; they cannot be violated unless the efficiency exceeds a certain bound. For example, in the Clauser-Horne test, the bound is ⅔≈67% (Eberhard, 199X; Larsson, 2000).

Fair sampling assumption

Usually, the fair sampling assumption (alternatively, the "no-enhancement assumption") is used in regard to this loophole. It states that the sample of detected pairs is representative of the pairs emitted, in which case the right-hand side in the equation above is reduced to 2, irrespective of the efficiency. This comprises a third postulate necessary for violation in low-efficiency experiments, in addition to the (two) postulates of local realism. There is no way to test experimentally whether a given experiment does fair sampling, as the number of emitted but undetected pairs is by definition unknown.

Double detections

In many experiments the electronics are such that simultaneous + and – counts from both outputs of a polariser can never occur, only one or the other being recorded. Under quantum mechanics, they will not occur anyway, but under a wave theory the suppression of these counts will cause even the basic realist prediction to yield unfair sampling. However, the effect is negligible if the detection efficiencies are low.

Communication, or locality

The Bell inequality is motivated by the absence of communication between the two measurement sites. In experiments, this is usually ensured simply by prohibiting any light-speed communication by separating the two sites and then ensuring that the measurement duration is shorter than the time it would take for any light-speed signal from one site to the other, or indeed, to the source. In one of Alain Aspect's experiments, inter-detector communication at light speed during the time between pair emission and detection was possible, but such communication between the time of fixing the detectors' settings and the time of detection was not. An experimental set-up without any such provision effectively becomes entirely "local", and therefore cannot rule out local realism. Additionally, the experiment design will ideally be such that the settings for each measurement are not determined by any earlier event, at both measurement stations.

John Bell supported Aspect's investigation of it[9](p. 109) and had some active involvement with the work, being on the examining board for Aspect’s PhD. Aspect improved the separation of the sites and did the first attempt on really having independent random detector orientations. Weihs et al. improved on this with a distance on the order of a few hundred meters in their experiment in addition to using random settings retrieved from a quantum system.[10] Scheidl et al. (2010) improved on this further by conducting an experiment between locations separated by a distance of 144 km.[11]

Disjoint sampling

John Bell assumed observations are obtained with a common hidden variable 'lambda'. However, 2-particle experiments violate that assumption. To estimate the correlation when the two measurement devices have parameters 'a' and 'b', a sample (of observations) is taken. To estimate the correlation when the devices have parameters 'a' and 'c', a second sample is taken. To estimate the correlation when the devices have parameters 'b' and 'c', a third sample is taken. Those three correlations are then used in Bell's original inequality and found to violate that inequality. But the statistics of sequential (disjoint) samples are different from the statistics of a single (joint) sample where all of the parameters 'a', 'b', and 'c' are set once and not changed. That condition can only be met if there are 3-particles (not 2). Bell's 3-parameter inequality holds without ambiguity for 3-particles measured jointly. 3-particle joint correlations inserted into Bell's inequality will not violate the inequality. Using disjoint correlations in joint inequalities is claimed to be the cause of inequality violation.

Failure of rotational invariance

The source is said to be "rotationally invariant" if all possible hidden variable values (describing the states of the emitted pairs) are equally likely. The general form of a Bell test does not assume rotational invariance, but a number of experiments have been analysed using a simplified formula that depends upon it. It is possible that there has not always been adequate testing to justify this. Even where, as is usually the case, the actual test applied is general, if the hidden variables are not rotationally invariant this can result in misleading descriptions of the results. Graphs may be presented, for example, of coincidence rate against the difference between the settings a and b, but if a more comprehensive set of experiments had been done it might have become clear that the rate depended on a and b separately. Cases in point may be Weihs' experiment (Weihs, 1998),[10] presented as having closed the locality loophole, and Kwiat’s demonstration of entanglement using an “ultrabright photon source” (Kwiat, 1999).[12]

Sources of error in (optical) Bell test experiments

In the case of Bell test experiments, if there are sources of error (that are not accounted for by the experimentalists) that might be of enough importance to explain why a particular experiment gives results in favor of quantum entanglement as opposed to local realism, they are called loopholes. Here some examples of existing and hypothetical experimental errors are explained. There are of course sources of error in all physical experiments. Whether or not any of those presented here have been found important enough to be called loopholes, in general or because of possible mistakes by the performers of some known experiment found in literature, is discussed in the subsequent sections. There are also non-optical Bell test experiments, which are not discussed here.

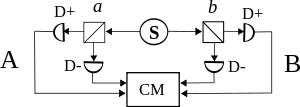

Example of typical experiment

The source S is assumed to produce pairs of "photons," one pair at a time with the individual photons sent in opposite directions. Each photon encounters a two-channel polarizer whose orientation can be set by the experimenter. Emerging signals from each channel are detected and coincidences counted by the "coincidence monitor" CM. It is assumed that any individual photon has to go one way or the other at the polarizer. The entanglement hypothesis states that the two photons in a pair (due to their common origin) share a wave function, so that a measurement on one of the photons affects the other instantaneously, no matter the separation between them. This effect is termed the EPR paradox (although it is not a true paradox). The Local realism hypothesis on the other hand states that measurement on one photon has no influence whatsoever on the other.

As a basis for our description of experimental errors let us consider a typical experiment of CHSH type (see picture to the right). In the experiment the source is assumed to emit light in the form of pairs of particle-like photons with each photon sent off in opposite directions. When photons are detected simultaneously (in reality during the same short time interval) at both sides of the "coincidence monitor" a coincident detection is counted. On each side of the coincidence monitor there are two inputs that are here named the "+" and the "-" input. The individual photons must (according to quantum mechanics) make a choice and go one way or the other at a two-channel polarizer. For each pair emitted at the source ideally either the + or the - input on both sides will detect a photon. The four possibilities can be categorized as ++, +−, −+ and −−. The number of simultaneous detections of all four types (hereinafter N++, N+-, N-+ and N--) is counted over a timespan covering a number of emissions from the source. Then the following is calculated:

(1) E = (N++ + N-- − N+- − N-+)/(N++ + N-- + N+- + N-+).

This is done with polarizer a rotated into two positions a and a′, and polarizer b into two positions b and b′, so that we get E(a,b),E(a,b′),E(a′,b) and E(a′,b′). Then the following is calculated:

(2) S = E(a, b) − E(a, b′) + E(a′, b) + E(a′ b′)

Entanglement and local realism give different predicted values on S, thus the experiment (if there are no substantial sources of error) gives an indication to which of the two theories better corresponds to reality.

Sources of error in the light source

The principal possible errors in the light source are:

- Failure of rotational invariance: The light from the source might have a preferred polarization direction, in which case it is not rotationally invariant.

- Multiple emissions: The light source might emit several pairs at the same time or within a short timespan causing error at detection.

Sources of error in the optical polarizer

- Imperfections in the polarizer: The polarizer might influence the relative amplitude or other aspects of reflected and transmitted light in various ways.

Sources of error in the detector or detector settings

- The experiment may be set up as not being able to detect photons simultaneously in the "+" and "-" input on the same side of the experiment. If the source may emit more than one pair of photons at any one instant in time or close in time after one another, for example, this could cause errors in the detection.

- Imperfections in the detector: failing to detect some photons or detecting photons even when the light source is turned off (noise).

Free choice of detector orientations

The experiment requires choice of the detectors' orientations. If this free choice were in some way denied then another loophole might be opened, as the observed correlations could potentially be explained by the limited choices of detector orientations. Thus, even if all experimental loopholes are closed, superdeterminism may allow the construction of a local realist theory that agrees with experiment.[13]

References

- ↑ I. Gerhardt, Q. Liu, A. Lamas-Linares, J. Skaar, V. Scarani, V. Makarov, C. Kurtsiefer (2011), "Experimentally faking the violation of Bell's inequalities", Phys. Rev. Lett. 107 (17): 170404, arXiv:1106.3224, Bibcode:2011PhRvL.107q0404G, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.170404

- ↑ Santos, E., The failure to perform a loophole-free test of Bell’s Inequality supports local realism. Foundations of Physics 34: 1643-1673 (2004)

- ↑ Philip M. Pearle (1970), "Hidden-Variable Example Based upon Data Rejection", Phys. Rev. D 2 (8): 1418–25, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.2.1418

- ↑ Anupam Garg, N.D. Mermin (1987), "Detector inefficiencies in the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen experiment", Phys. Rev. D 25 (12): 3831–5, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.35.3831

- ↑ Jan-Åke Larsson (1998), "Bell's inequality and detector inefficiency", Phys. Rev. A 57 (5): 3304–8, doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.57.3304

- ↑ M.A. Rowe, D. Kielpinski, V. Meyer, C.A. Sackett, W.M. Itano, C. Monroe, D.J. Wineland (2001), "Experimental violation of a Bell's inequality with efficient detection", Nature 409 (6822): 791–94, doi:10.1038/35057215

- ↑ Ansmann, M.; Wang, H.; Bialczak, R. C.; Hofheinz, M.; Lucero, E.; Neeley, M.; O'Connell, A. D.; Sank, D.; Weides, M.; Wenner, J. & et al. (2009), "Violation of Bell's inequality in Josephson phase qubits", Nature 461: 504–6, doi:10.1038/nature08363

- ↑ Pfaff, W.; Taminiau, T. H.; Robledo, L.; Bernien, H.; Markham, M.; Twitchen, D. J. & Hanson, R. (2012), "Demonstration of entanglement-by-measurement of solid-state qubits", Nature Physics 9: 29–33, doi:10.1038/nphys2444

- ↑ J. S. Bell (1987), Atomic-cascade photons and quantum-mechanical nonlocality Reprinted as Chapter 13 of J. S. Bell, Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics, (Cambridge University Press 1987)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 G. Weihs, T. Jennewein, C. Simon, H. Weinfurter, A. Zeilinger (1998), "Violation of Bell's inequality under strict Einstein locality conditions", Phys. Rev. Lett. 81: 5039, arXiv:quant-ph/9810080, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.5039

- ↑ T. Scheidl et al. (2010), "Violation of local realism with freedom of choice", Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107: 19708, doi:10.1073/pnas.1002780107

- ↑ P.G. Kwiat, E. Waks, A.G. White, I. Appelbaum, P.H. Eberhard (1999), "Ultrabright source of polarization-entangled photons", Physical Review A 60 (2): R773–6, arXiv:quant-ph/9810003, doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.60.R773

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/16/opinion/sunday/is-quantum-entanglement-real.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- J. S. Bell, BBC Radio interview with Paul Davies, 1985

- J. S. Bell, Free variables and local causality, Epistemological Letters, Feb. 1977. Reprinted as Chapter 12 of J. S. Bell, Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics, (Cambridge University Press 1987)

- J.F. Clauser, M.A. Horne (1974), "Experimental consequences of objective local theories", Phys. Rev. D 10 (2): 526–35, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.10.526

- S.J. Freedman, J.F. Clauser (1972), "Experimental test of local hidden-variable theories", Phys. Rev. Lett. 28: 938, doi:10.1103/physrevlett.28.938

- Caroline H. Thompson (1996), "The Chaotic Ball: An Intuitive Analogy for EPR Experiments", Found. Phys. Lett. 9 (4): 357–82, arXiv:quant-ph/9611037, doi:10.1007/BF02186307

- W. Tittel, J. Brendel, B. Gisin, T. Herzog, H. Zbinden, N. Gisin (1998), "Experimental demonstration of quantum-correlations over more than 10 kilometers", Physical Review A 57: 3229, arXiv:quant-ph/9707042, doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.57.3229

- W. Tittel, J. Brendel, N. Gisin, H. Zbinden (1999), "Long-distance Bell-type tests using energy-time entangled photons", Phys. Rev. A 59 (6): 4150–63, arXiv:quant-ph/9809025, doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.59.4150