Logical biconditional

In logic and mathematics, the logical biconditional (sometimes known as the material biconditional) is the logical connective of two statements asserting "p if and only if q", where q is an antecedent and p is a consequent.[1] This is often abbreviated p iff q. The operator is denoted using a doubleheaded arrow (↔), a prefixed E (Epq), an equality sign (=), an equivalence sign (≡), or EQV. It is logically equivalent to (p → q) ∧ (q → p), or the XNOR (exclusive nor) boolean operator. It is equivalent to "(not p or q) and (not q or p)". It is also logically equivalent to "(p and q) or (not p and not q)", meaning "both or neither".

The only difference from material conditional is the case when the hypothesis is false but the conclusion is true. In that case, in the conditional, the result is true, yet in the biconditional the result is false.

In the conceptual interpretation, a = b means "All a 's are b 's and all b 's are a 's"; in other words, the sets a and b coincide: they are identical. This does not mean that the concepts have the same meaning. Examples: "triangle" and "trilateral", "equiangular trilateral" and "equilateral triangle". The antecedent is the subject and the consequent is the predicate of a universal affirmative proposition.

In the propositional interpretation, a ⇔ b means that a implies b and b implies a; in other words, that the propositions are equivalent, that is to say, either true or false at the same time. This does not mean that they have the same meaning. Example: "The triangle ABC has two equal sides", and "The triangle ABC has two equal angles". The antecedent is the premise or the cause and the consequent is the consequence. When an implication is translated by a hypothetical (or conditional) judgment the antecedent is called the hypothesis (or the condition) and the consequent is called the thesis.

A common way of demonstrating a biconditional is to use its equivalence to the conjunction of two converse conditionals, demonstrating these separately.

When both members of the biconditional are propositions, it can be separated into two conditionals, of which one is called a theorem and the other its reciprocal. Thus whenever a theorem and its reciprocal are true we have a biconditional. A simple theorem gives rise to an implication whose antecedent is the hypothesis and whose consequent is the thesis of the theorem.

It is often said that the hypothesis is the sufficient condition of the thesis, and the thesis the necessary condition of the hypothesis; that is to say, it is sufficient that the hypothesis be true for the thesis to be true; while it is necessary that the thesis be true for the hypothesis to be true also. When a theorem and its reciprocal are true we say that its hypothesis is the necessary and sufficient condition of the thesis; that is to say, that it is at the same time both cause and consequence.

Definition

Logical equality (also known as biconditional) is an operation on two logical values, typically the values of two propositions, that produces a value of true if and only if both operands are false or both operands are true.

Truth table

The truth table for  (also written as A ≡ B, A = B, or A EQ B) is as follows:

(also written as A ≡ B, A = B, or A EQ B) is as follows:

| INPUT | OUTPUT | |

| A | B | A  B B |

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

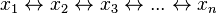

More than two statements combined by  are ambiguous:

are ambiguous:

may be meant as

may be meant as  ,

,

or may be used to say that all  are together true or together false:

are together true or together false:

Only for zero or two arguments this is the same.

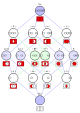

The following truth tables show the same bit pattern only in the line with no argument and in the lines with two arguments:

meant as equivalent to

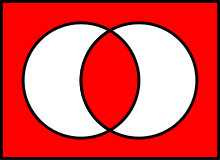

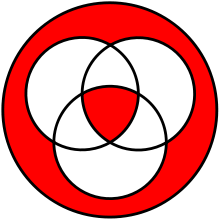

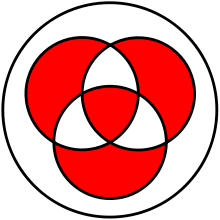

The central Venn diagram below,

and line (ABC ) in this matrix

represent the same operation.

meant as shorthand for

The Venn diagram directly below,

and line (ABC ) in this matrix

represent the same operation.

The left Venn diagram below, and the lines (AB ) in these matrices represent the same operation.

Venn diagrams

Red areas stand for true (as in ![]() for and).

for and).

|

|

|

Properties

commutativity: yes

|

|

|

|

associativity: yes

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

distributivity: Biconditional doesn't distribute over any binary function (not even itself),

but logical disjunction (see there) distributes over biconditional.

idempotency: no

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

monotonicity: no

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

truth-preserving: yes

When all inputs are true, the output is true.

|

|

|

|

falsehood-preserving: no

When all inputs are false, the output is not false.

|

|

|

|

Walsh spectrum: (2,0,0,2)

Nonlinearity: 0 (the function is linear)

Rules of inference

Like all connectives in first-order logic, the biconditional has rules of inference that govern its use in formal proofs.

Biconditional introduction

Biconditional introduction allows you to infer that, if B follows from A, and A follows from B, then A if and only if B.

For example, from the statements "if I'm breathing, then I'm alive" and "if I'm alive, then I'm breathing", it can be inferred that "I'm breathing if and only if I'm alive" or, equally inferrable, "I'm alive if and only if I'm breathing."

B → A A → B ∴ A ↔ B

B → A A → B ∴ B ↔ A

Biconditional elimination

Biconditional elimination allows one to infer a conditional from a biconditional: if ( A ↔ B ) is true, then one may infer one direction of the biconditional, ( A → B ) and ( B → A ).

For example, if it's true that I'm breathing if and only if I'm alive, then it's true that if I'm breathing, I'm alive; likewise, it's true that if I'm alive, I'm breathing.

Formally:

( A ↔ B ) ∴ ( A → B )

also

( A ↔ B ) ∴ ( B → A )

Colloquial usage

One unambiguous way of stating a biconditional in plain English is of the form "b if a and a if b". Another is "a if and only if b". Slightly more formally, one could say "b implies a and a implies b". The plain English "if'" may sometimes be used as a biconditional. One must weigh context heavily.

For example, "I'll buy you a new wallet if you need one" may be meant as a biconditional, since the speaker doesn't intend a valid outcome to be buying the wallet whether or not the wallet is needed (as in a conditional). However, "it is cloudy if it is raining" is not meant as a biconditional, since it can be cloudy while not raining.

See also

- If and only if

- Logical equivalence

- Logical equality

- XNOR gate

- Biconditional elimination

- Biconditional introduction

Notes

- ↑ Handbook of Logic, page 81

References

- Brennan, Joseph G. Handbook of Logic, 2nd Edition. Harper & Row. 1961

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

This article incorporates material from Biconditional on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.