Lochnagar mine

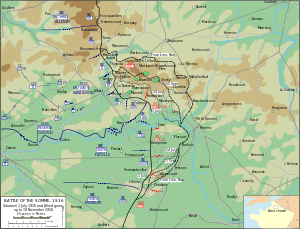

The Lochnagar mine was a mine dug by the 179th Tunnelling Company Royal Engineers, under a German field fortification known as Schwabenhöhe, in the front line south of the village of La Boisselle in the Somme département of France. The mine was sprung at 7:28 a.m. on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, as the infantry of the British 34th Division, which was composed of Pals battalion from the north of England, attacked the positions of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 of the German 28th Reserve Division, mainly recruited from Baden, on either side of La Boisselle. The crater was captured and held by British troops but the attack on either flank was defeated by German small-arms and artillery fire, except on the extreme right flank and just south of La Boisselle, north of the new crater. The 34th Division incurred the largest number of casualties of the British divisions which attacked on 1 July. The crater has been preserved as a memorial, where a service is held on 1 July each year.

Background

1915

Fighting in no man's land between the French and German garrisons continued at the west end of La Boisselle, where the opposing lines were 200 yards (180 m) apart, even during lulls along the rest of the Somme front. On the night of 8/9 March, a German sapper inadvertently broke into French mine gallery, which was found to have been charged with explosives; a group of volunteers took 45 nerve racking minutes to dismantle the charge and cut the firing cables. From April 1915 – January 1916, sixty-one mines were sprung around the Granathof, some loaded with 20,000–25,000 kilograms (44,000–55,000 lb) of explosives.[1] The French mine workings were taken over when the British moved into the Somme front. Elaborate precautions were taken to preserve secrecy, since no continuous front line trench ran through the area opposite the west end of La Boisselle and the British front line. The area became known to the British as the Glory Hole and was defended on the British side by posts near the mine shafts.[2]

Prelude

1916

The mines were planted at the end of galleries dug by the 179th Tunnelling Company Royal Engineers, on either side of the salient around La Boisselle and were intended to destroy German positions and create crater lips, to block German enfilade fire along no man's land. The Lochnagar mine was named after Lochnagar Street, the trench from which the gallery was driven. For silence the tunnellers used bayonets with spliced handles and worked barefoot on a floor covered with sandbags. Flints were carefully prised out of the chalk and laid on the floor, if the bayonet was manipulated two-handed, an assistant caught the dislodged material. Spoil was placed in sandbags and passed hand-by-hand, along a row of miners sitting on the floor and stored along the side of the tunnel, later to be used to tamp the charge.[3] The tunnellers also dug a gallery across no man's land to a point close to the Lochnagar mine.[4]

The completed Lochnagar tunnel was 4.5 by 2.5 feet (1.37 m × 0.76 m) and had been excavated at a rate of about 18 inches (46 cm) per day until about 1,030 feet (310 m) long, with the galleries beneath the Schwabenhöhe The mines were laid without interference by German miners but as the explosives were placed, German miners could be heard below Lochnagar and above Y Sap. Lochnagar was loaded with 60,000 pounds (27,000 kg) of Ammonal, in two charges of 36,000 pounds (16,000 kg) and 24,000 pounds (11,000 kg), 60 apart and 52 feet (16 m) deep. Just north of the village, Y Sap was charged with 40,600 pounds (18,400 kg) of Ammonal.[3] Two smaller mines of 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) each, were planted from galleries dug from Inch Street Trench.[4]

Battle

1 July

The mine was detonated at 7:28 a.m. on 1 July 1916, the first day on the Somme. The Lochnagar mine, along with the Y Sap mine, were the largest mines ever detonated.[5] The sound of the blast was considered the loudest man-made noise in history up to that point, with reports suggesting it was heard in London.[6] The Lochnagar mine lay on the sector assaulted by the Grimsby Chums Pals battalion (10th Battalion, The Lincolnshire Regiment).[5] When the main attack began at 7:30 a.m., the Grimsby Chums occupied the crater and began to fortify the eastern lip, which dominated the surrounding ground. During the day German artillery fired into Sausage Valley and in the afternoon began systematically to shell areas and then fire bursts from machine-guns to catch anyone who moved. German artillery also began to bombard the crater, where wounded and lost men sought shelter, particularly those in Sausage Valley to the south of the village. British artillery began to fire on the crater, which led to shell bursts on both sides, leaving the men inside with nowhere to hide. A British aircraft flew low overhead and a soldier waved a dead man's shirt, at which the aeroplane flew away and the British shelling stopped.[7]

The explosion of the Lochnagar and Y Sap mines was witnessed from the air by 2nd Lieutenant Cecil Lewis of 3 Squadron, flying a Morane Parasol,

At Boisselle the earth heaved and flashed, a tremendous and magnificent column rose up in the sky. There was an ear-splitting roar drowning all the guns, flinging the machine sideways in the repercussing air. The earth column rose higher and higher to almost 4,000 feet (1,200 m). There it hung, or seemed to hang, for a moment in the air, like the silhouette of some great cypress tree, then fell away in a widening cone of dust and debris. A moment later came the second mine. Again the roar, the upflung machine, the strange gaunt silhouette invading the sky. Then the dust cleared and we saw the two white eyes of the craters. The barrage had lifted to the second-line trenches, the infantry were over the top, the attack had begun.(Cecil Lewis, Sagittarius Rising, 1936)[8]

Aircraft from 3 Squadron flew over the III Corps area and observers reported that the 34th Division had reached Peake Wood on the right flank, increasing the size of the salient which had been driven into the German lines north of Fricourt but that the villages of La Boisselle and Ovillers had not fallen. On 3 July, air observers noted flares lit in the village during the evening, which were used to plot the positions reached by British infantry.[9] The tunnel was used to contact troops near the new crater and during the afternoon, troops from the 9th Cheshires of the 19th Division began to move forward and a doctor was sent from the Field Ambulance during the night.[10] By 2:50 a.m. on 2 July, most of the 9th Cheshires had reached the crater and the German trenches adjacent, from which they repulsed several German counter-attacks during the rest of the night and the morning.[11] On the evening of 2 July, the evacuation of wounded began and on 3 July, troops from the crater and the vicinity, pushed forward to the south-east and occupied a small area against little opposition.[12]

Commemoration

William Orpen an official war artist saw the mine crater in 1916, while touring the Somme battlefield collecting subjects for paintings and described a wilderness of chalk dotted with shrapnel. John Masefield also toured the Somme while preparing a book, published as The Old Front Line (1917), in which he also described the area around the crater as dazzlingly white and painful to look at.[13] After the war the café de la Grand Mine was built nearby and after the Second World War, many of the smaller craters were filled but the Lochnagar crater still exists.[14] Attempts to fill it in were resisted and the land was eventually purchased by an Englishman, Richard Dunning, to ensure it would be preserved. Dunning had decided to purchase a section of the former front lines after reading The Old Front Line. He made more than 200 enquiries into land over a four year period in the 1970s and was unexpectedly presented with the opportunity to buy the crater by the agricultural landowner who had intended to fill it.[15] The site had been used by cross-country motorbikes and fly tipping. Dunning erected a memorial cross on the rim of the crater in 1986, using reclaimed timber from a Tyneside church. This cross was struck by lightning shortly after its installation and was repaired with metal banding; the site attracts some 200,000 visitors per year.[5] There is an annual memorial service on 1 July, to commemorate the detonation of the mine and the British, French and German war dead.[5][16] The service has been attended by royalty and politicians and as part of the ceremony, poppy petals are scattered into the crater by the attendees.[16]

Gallery

-

La Boisselle mine crater, August 1916 (IWM Q 912) -

Troops passing Lochnagar Crater, October 1916 (IWM Q 1479) -

Orpen: Mines and the Bapaume Road, La Boisselle (Art.IWMART2962) -

Orpen: The Great Mine, La Boisselle (Art.IWMART2379) -

Lochnagar Crater, La Boisselle 1984

-

Lochnagar Crater, Ovillers

See also

- List of the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions

Footnotes

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, pp. 62–65.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 38, 371.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Edmonds 1932, p. 375.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Shakespear 1921, p. 37.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Legg 2013.

- ↑ Waugh 2014.

- ↑ Middlebrook 1971, pp. 135, 218.

- ↑ Lewis 1936, p. 90.

- ↑ Jones 1928, p. 212.

- ↑ Shakespear 1921, pp. 41, 45.

- ↑ Wyrall 1932, p. 41.

- ↑ Shakespear 1921, p. 48.

- ↑ Masefield 1917, pp. 70–73.

- ↑ Gliddon 1987, pp. 255–256.

- ↑ Skinner 2012, p. 192.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Skinner 2012, p. 195.

Bibliography

- Books

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-185-7.

- Gliddon, G. (1987). When the Barrage Lifts: A Topographical History and Commentary on the Battle of the Somme 1916. Norwich: Gliddon Books. ISBN 0-947893-02-4.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force (PDF) II (Imperial War Museum and N & M Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 1-84342-413-4. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Lewis, C. A. (1977) [1936]. Sagittarius Rising: The Classic Account of Fying in the First World War (2nd Penguin ed.). London: Peter Davis. ISBN 0-14-00-4367-5. OCLC 473683742.

- Masefield, J. (1917). The Old Front Line (PDF). New York: Macmillan. OCLC 869145562. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Middlebrook, M. (1971). The First Day on the Somme. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-139071-9.

- Shakespear, J. (2001) [1921]. The Thirty-Fourth Division, 1915–1919: The Story of its Career from Ripon to the Rhine (N & M Press ed.). London: H. F. & G. Witherby. ISBN 1-84342-050-3. OCLC 6148340. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Sheldon, J. (2006) [2005]. The German Army on the Somme 1914–1916 (Pen & Sword Military ed.). London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 1-84415-269-3.

- Skinner, J. (2012). Writing the Dark Side of Travel. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0-85745-341-9. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Wyrall, E. (2009) [1932]. The Nineteenth Division 1914–1918 (N & M Press ed.). London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 1-84342-208-5.

- Websites

- Legg, J. "Lochnagar Mine Crater Memorial, La Boisselle, Somme Battlefields". www.greatwar.co.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- Waugh, I. (2014). "WW1 Trip to the Somme". Old British News. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lochnagar mine. |

- Lochnagar Crater - The Official Site

- 360° Panoramic View

- La Boisselle Study Group

- Ovillers-La-Boisselle photo essay

- Grimsby Roll of Honour, 1914–1919

- Reid, P. Lochnagar Crater, La Boisselle

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||