Llanfaes

| Llanfaes | |

Llanfaes |

|

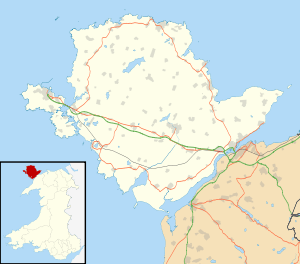

| OS grid reference | SH603778 |

|---|---|

| Principal area | Anglesey |

| Ceremonial county | Gwynedd |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BEAUMARIS |

| Postcode district | LL58 |

| Dialling code | +01248 |

| Police | North Wales |

| Fire | North Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| EU Parliament | Wales |

| UK Parliament | Ynys Môn |

| Welsh Assembly | Ynys Môn |

Coordinates: 53°16′45″N 4°05′44″W / 53.27928°N 4.09565°W

Llanfaes (formerly also known as Llanmaes) is a small village on the island of Anglesey, Wales, located on the shore of the eastern entrance to the Menai Strait, the tidal waterway separating Anglesey from the north Wales coast. Its natural harbour made it an important medieval port and it was briefly the capital of the kingdom of Gwynedd. Following Prince Madoc's Rebellion, Edward I removed the Welsh population from the town and rebuilt the port a mile to the south at Beaumaris.

Name

The current settlement of Llanfaes was originally known as Llan Ffagan Fach ("Church" or "Monastery of Fagan the Little") in honour of a Ffagan who founded a church at the site.[1] Saint Fagan was supposed to have been a 2nd-century apostle among the Welsh and is also commemorated at St. Fagan's in Cardiff. The present name doesn't refer to a saint, but instead is simply Welsh for the "Church" or "Monastery in the Meadow".

Although both towns are pronounced Llanfaes in Welsh, the British government distinguishes an identically-named settlement in Glamorgan by spelling it Llanmaes. However, the town on Anglesey has also historically been known by that spelling as well. An unofficial Welsh variant is Llan-faes with a hyphen.

History

In the medieval kingdom of Gwynedd, Llanfaes functioned as the royal demesne (Welsh: maerdref) and seat of local governance for the commote of Dindaethwy in cantref Mon.[2] King Cynan Dindaethwy maintained his royal court (Welsh: llys) in the town around the turn of the 9th century, but he was killed amid a protracted struggle against a rival named Hywel. Following Cynan's death, there was a major Battle of Llanmaes (Welsh: Gwaith Llanfaes) recorded in all the Welsh annals. Various sources conjecture that the battle marked an invasion by Mercians, Wessaxons, or Vikings, but the original sources simply do not record the combatants.[3][4][5] Afterwards, however, the subsequent Merfynion dynasty established its northern court at Aberffraw on the opposite side of the island instead.

A wooden fortress—square with a round tower at each angle—was constructed at the site by the Normans Hugh the Wolf of Chester and Hugh the Red of Shrewsbury during their 1098 invasion.[6] During the Battle of Anglesey Sound between the Two Hughs and King Magnus Barefoot of Norway, Magnus was said to have personally shot Hugh the Red through the eye with an arrow before discovering whom he was fighting and withdrawing back to the north.[7]

Llanmaes was still (or again) a maerdref during the 12th and 13th centuries, when its royal estates encompassed 780 acres.[8] A stream powered a mill there and it was the northernmost ferry across the Menai Strait separating Anglesey from the mainland. The town also had a leper colony to its north.[8] By the end of the 13th century, it had become such an important trading center that some estimates credit its trade in ale, wine, wool, and hides with 70% of Gwynedd's tariff revenue.[8][9] It also held two annual fairs and maintained a herring fishery.[9] When Llywelyn the Great's wife Joan, the daughter of King John of England, died in 1237, her body was buried at Llanmaes and a Franciscan monastery constructed at Llywelyn's expense at the site.

The Llanmaes suffered during the rebellion of Madog ap Llywelyn (1294–95),[8] at the end of which Edward I visited Llanfaes and ordered the construction of the new castle and town of Beaumaris nearby as part of his pacification campaign. The nearby site of Porth y Wygyr ("Vikingport") or Cerrig y Gwyddyl ("Irishstone") was chosen and Edward evicted Llanmaes's Welsh population to the opposite coast of the island, turning Rhosyr into "Newborough". Beaumaris then appropriated Llanmaes's former ferry and coastal trade.

The monastery at Llanfaes was restored with help from Edward II (r. 1307–27) but then thoroughly plundered and destroyed by agents of Henry IV as a punishment for its friars' support of the Glyndŵr Rising (1400–1415). Whatever was subsequently rebuilt was dissolved with the other monasteries by Henry VIII in 1537. Afterwards, the church was used a barn and Joan's stone coffin as a watering trough[10] before being removed along with the monastery's other furnishings to St. Mary's and St. Nicholas's in Beaumaris.[11]

The fortress first established by the Normans was held during the English Civil War by Sir Thomas Cheadle on behalf of the Parliament, but was taken from him by Col. John Robinson in 1645 or '46.[6]

See also

- Beaumaris, the nearby town which replaced Llanmaes

References

- ↑ Morgan, Thomas. Handbook of the Origin of Place-names in Wales and Monmouthshire, p. 138. Thomas Morgan (Merthyr Tydfil), 1887.

- ↑ Lloyd, John E. A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest, Vol. 1, p. 232. Longmans, Green, & Co. (London), 1911. Accessed 20 Feb 2013.

- ↑ Medieval Latin: an'. Gueith lannmaes. Harleian MS. 3859. Op. cit. Phillimore, Egerton. Y Cymmrodor 9 (1888), pp. 141–83. (Latin)

- ↑ Medieval Latin: Anus bellum llan mais. Public Records Office MS. E.164/1. (Latin)

- ↑ "818—Battle in Anglesey, called Gwaith Llanfaes." Parry, Henry (trans.) Archaeologia Cambrensis, Vol. IX, 32. "Brut y Saeson", p. 63". J. Russell Smith (London), 1863. Accessed 20 Feb 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Carlisle, Nicholas. A Topographical Dictionary of Wales, a Continuation of the Topography of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, p. 308. Oxford Univ. Press, 1811.

- ↑ Lloyd, Vol. 2, p. 408.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Gwynedd Archaeological Trust. "Llanmaes". Accessed 20 Feb 2013.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 The Harlech Medieval Society. "History of Beaumaris". 2013. Accessed 20 Feb 2013.

- ↑ Hughes, William. Diocesan Histories: Bangor, Appendix D, pp. 187–188. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (London), 1911.

- ↑ Loomis, Richard. New House & Guto'r Glyn in 1492, p. 118. Richard Loomis, 2005. Accessed 20 Feb 2013.

External links

- "Llanfaes" at the Gwynedd Archaeological Trust

- "Llanfaes" on Geograph.org.uk

- "Llanfaes" in Ordnance Survey maps at A Vision of Britain Through Time

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||