List of most massive known stars

This is a list of the most-massive stars so far discovered, in solar masses (M☉).

Uncertainties and caveats

Most of the masses listed below are contested and, being the subject of current research, remain under review and subject to revision.

The masses listed in the table below are inferred from theory, using difficult measurements of the stars’ temperatures and absolute brightnesses. All the listed masses are uncertain: both the theory and the measurements are pushing the limits of current knowledge and technology. Either measurement or theory, or both, could be incorrect. For example, VV Cephei could be between 25–40 M☉, or 100 M☉, depending on which property of the star is examined.

Massive stars are rare; astronomers must look very far from the Earth to find one. All the listed stars are many thousands of light years away and that alone makes measurements difficult. In addition to being far away, many stars of such extreme mass are surrounded by clouds of outflowing gas; the surrounding gas interferes with the already difficult-to-obtain measurements of stellar temperatures and brightnesses and greatly complicates the issue of estimating internal chemical compositions. For some methods, different determinations of chemical composition lead to different estimates of mass. In addition, the clouds of gas make it difficult to judge whether the star is just a single supermassive object or, instead, a multiple star system. A number of the "stars" listed below may actually consist of two or more companions in close orbit, each star being massive in itself but not necessarily supermassive. Other combinations are possible – for example a supermassive star with one or more smaller companions or more than one giant star. Without being able to see inside the surrounding cloud, it is difficult to know the truth of the matter.

Amongst the most reliable listed masses are those for NGC 3603-A1, WR21a and WR20a, which were obtained from orbital measurements. These entities are members of (different) binary star systems and it is possible to measure in both cases the individual masses of the two stars by studying their orbital motions, using Kepler's laws of planetary motion. This involves measuring their radial velocities and also their light curves, as they are eclipsing binaries. The derivation of binary masses requires relatively limited information about the orbital parameters but one key value that isn't always accurately known is the inclination. Without this only a minimum value for the masses can be derived, so several binaries are shown with masses as greater than a particular value. For eclipsing binaries, the inclination can be derived with better accuracy. The list gives only the inferred masses of stars according to recent best estimates and does not include superseded estimates of mass.

Relevance of stellar evolution

Some stars may once have been heavier than they are today. It is likely that many have lost tens of solar masses of material in the process of degassing, or in sub-supernova and supernova impostor explosion events.

There are also – or rather were – stars that might have appeared on the list but no longer exist as stars. Today we see only the debris (see for example hypernovae and supernova remnant). The masses of the precursor stars that fueled these cataclysms can be estimated from the type of explosion and the energy released, but those masses are not listed here.

List of the most massive stars

Known stars with an estimated mass of 25 or greater M☉, including the stars of Arches cluster, Cygnus OB2 cluster, Pismis 24 cluster and R136 cluster. Masses are their current (evolutionary) mass, not their initial (formation) mass. The list is far from complete, although the majority of stars thought to be more than 100 M☉ are shown.

.jpg)

| Star name | Mass (M☉, Sun = 1) |

|---|---|

| R136a1 [1] | 256 |

| BAT99-98[2] | 226 |

| BAT99-116[3] | 190 |

| R136a2 [1] | 179 |

| VFTS 682 | 150 |

| NGC 3603-B[1] | 132 |

| R136c | ≥130 |

| R136a3 [2] | 130 |

| HD 269810 | 130 |

| WR 42e[4] | 125-135[lower-alpha 1] |

| Arches-F9 | 111–131 |

| NGC 3603-A1a | 120 |

| η Carinae A | 120 |

| R136b | 118 |

| HD 93250 | 118 |

| R145[5] | >116 + >48[lower-alpha 2] |

| Cygnus OB2-7 | 114 |

| NGC 3603-C[1] | 113 |

| Melnick 42 | 113 |

| Cygnus OB2-12 | 110 |

| WR 25 | 110 |

| Arches-F1 | 101–119 |

| Arches-F6 | 101–119 |

| Peony Star[6] | 100 |

| 516 Cygnus | 100 |

| Cluster R136a | About 20 more stars around 100 |

| HD 93129 A | 95 |

| Arches-F7 | 86–102 |

| NGC 3603-A1b | 92 |

| 771 Cygnus | 90 |

| HD 38282 A | 90 |

| The Pistol Star | 86-92 |

| Arches-F15 | 80–97 |

| WR21a A[7] | 87 |

| WR20a A | 83 |

| WR20a B | 82 |

| Sk -71 51[8] | 80 |

| Cygnus OB2-8B | 80 |

| HD 38282 B | 80 |

| R139 A[9] | 78 |

| V429 Carinae A | 78 |

| WR 22 | 78 |

| Pismis 24-17[10] | 78 |

| Arches-F12 | 70–82 |

| Cygnus OB2-10 | 75 |

| Arches-F18 | 67–82 |

| Var 83 in M33 | 60–85 |

| Cygnus OB2-8C | 71 |

| Arches-F4 | 66–76 |

| R126 | 70 |

| Companion to M33 X-7[11] | 70 |

| AG Carinae | 70 |

| BD+43° 3654 | 70 |

| HD 5980 A | 58-79 |

| Pismis 24-1 SW | 66 |

| LBV 1806-20 A + B | A=65, B=65 |

| Arches-F28 | 66–76 |

| LH54-425 A | 62 |

| Arches-F21 | 56–70 |

| Arches-F10 | 55–69 |

| HD 148937[12] | 60 |

| Arches-F14 | 54–65 |

| HD 5980 B | 51-67 |

| WR 102ea[13] | 58 |

| Cygnus OB2-11 | 58 |

| Arches-F3 | 52–63 |

| CD Crucis A[14] | 57 |

| Arches-B1 | 50–60 |

| Plaskett's star B | 56 |

| BD+40° 4210 | 54 |

| Plaskett's star A | 54 |

| WR21a B[15] | 53 |

| HD 93129A B[16] | 52 |

| Cygnus OB2-4 | 52 |

| Arches-F20 | 47–57 |

| Arches-F16 | 46–56 |

| WR102c[6] | 45–55 |

| CD Crucis B[14] | 48 |

| Arches-F8 | 43–51 |

| Sher 25 in NGC 3603 | 40–52 |

| Arches-F2 | 42–49 |

| S Doradus | 45 |

| IRS-8*[17] | 44.5 |

| Cygnus OB2-8A A | 44.1 |

| Cygnus OB2-1 | 44 |

| α Camelopardalis | 43 |

| Pismis 24-2 | 43 |

| χ2 Orionis | 42.3 |

| Cygnus OB2-6 | 42 |

| ε Orionis | 40 |

| RW Cephei | 40 |

| θ1 Orionis C | 40 |

| ζ Puppis | 22.5-56.6 |

| Companion to NGC 300 X-1[18] | 38 |

| Pismis 24-16 | 38 |

| Pismis 24-25 | 38 |

| Cygnus OB2-8A B | 37.4 |

| LH54-425 B | 37 |

| ζ1 Scorpii | 36 |

| Pismis 24-13 | 35 |

| Companion to IC 10 X-1[19] | 35 |

| Cygnus OB2-9 A | >34 |

| Arches-F5 | 31–36 |

| Cygnus OB2-18 | 33 |

| ζ Orionis | 33 |

| 19 Cephei | 30–35 |

| ξ Persei | 26–36 |

| Cygnus OB2-5 A | 31 |

| γ Velorum A | 30 |

| P Cygni | 30 |

| Cygnus OB2-9 B | >30 |

| IRS 15[20] | 26 |

| 6 Cassiopeiae[21] | 25 |

| Pismis 24-3 | 25 |

| KY Cygni | 25 |

| NGC 7538 S[22] | 25 |

| VFTS 102 | 25 |

| ρ Cassiopeiae | 14-30 |

| Wolf-Rayet star |

| O-class star |

| B-class star |

| Luminous blue variable star |

| Hypergiant |

- ↑ This unusual measurement was made by assuming the star was ejected from a three-body encounter in NGC 3603. This assumption also means that the current star is the result of a merger between two original close binary components. The mass is consistent with evolutionary mass for a star with the observed parameters.

- ↑ These are minimum values with the orbital solution still uncertain.

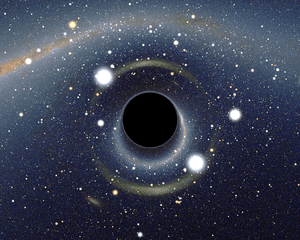

Black holes

Black holes are the end point evolution of massive stars. Technically they are not stars, as they no longer generate heat and light via nuclear fusion in their cores.

- Stellar black holes are objects with approximately 4–15 M☉.

- Intermediate-mass black holes range from 100–10000 M☉.

- Supermassive black holes are in the range of millions or billions M☉.

Eddington's size limit

The limit on mass arises because stars of greater mass have a higher rate of core energy generation, their luminosity increasing far out of proportion to their mass. For a sufficiently massive star the outward pressure of radiant energy generated by nuclear fusion in the star’s core exceeds the inward pull of its own gravity. This is called the Eddington limit. Beyond this limit, a star ought to push itself apart, or at least shed enough mass to reduce its internal energy generation to a lower, maintainable rate. In theory, a more massive star could not hold itself together, because of the mass loss resulting from the outflow of stellar material. In practice the theoretical Eddington Limit must be modified for high luminosity stars and the empirical Humphreys Davidson Limit is derived.[23]

Astronomers have long theorized that as a protostar grows to a size beyond 120 M☉, something drastic must happen. Although the limit can be stretched for very early Population III stars, and the exact value is uncertain, if any stars still exist above 150-200 M☉, they would challenge current theories of stellar evolution. Studying the Arches cluster, which is the densest known cluster of stars in our galaxy, astronomers have confirmed that stars in that cluster do not occur any larger than about 150 M☉. One theory to explain rare ultramassive stars that exceed this limit, for example in the R136 star cluster, is the collision and merger of two massive stars in a close binary system.[24]

See also

- Luminous blue variable

- Wolf–Rayet star

- Hypergiant

- List of least massive stars

- List of largest known stars

- List of most luminous stars

- List of brightest stars

- Lists of stars

- Supergiant

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Crowther, P. A.; Schnurr, O.; Hirschi, R.; Yusof, N.; Parker, R. J.; Goodwin, S. P.; Kassim, H. A. (2010). "The R136 star cluster hosts several stars whose individual masses greatly exceed the accepted 150 M⊙ stellar mass limit". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 408 (2): 731. arXiv:1007.3284. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.408..731C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17167.x.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hainich, R.; Rühling, U.; Todt, H.; Oskinova, L. M.; Liermann, A.; Gräfener, G.; Foellmi, C.; Schnurr, O.; Hamann, W. -R. (2014). "The Wolf-Rayet stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud". Astronomy & Astrophysics 565: A27. arXiv:1401.5474. Bibcode:2014A&A...565A..27H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322696.

- ↑ Crowther, P. A.; Schnurr, O.; Hirschi, R.; Yusof, N.; Parker, R. J.; Goodwin, S. P.; Kassim, H. A. (2010). "The R136 star cluster hosts several stars whose individual masses greatly exceed the accepted 150 M⊙ stellar mass limit". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 408 (2): 731. arXiv:1007.3284. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.408..731C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17167.x.

- ↑ Gvaramadze; Kniazev; Chene; Schnurr (2012). "Two massive stars possibly ejected from NGC 3603 via a three-body encounter". arXiv:1211.5926v1 [astro-ph.SR].

- ↑ Schnurr, O.; Moffat, A. F. J.; Villar-Sbaffi, A.; St-Louis, N.; Morrell, N. I. (2009). "A first orbital solution for the very massive 30 Dor main-sequence WN6h+O binary R145". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 395 (2): 823. arXiv:0901.0698. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.395..823S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.14437.x.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Barniske, A.; Oskinova, L. M.; Hamann, W. -R. (2008). "Two extremely luminous WN stars in the Galactic center with circumstellar emission from dust and gas". Astronomy and Astrophysics 486 (3): 971. arXiv:0807.2476. Bibcode:2008A&A...486..971B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809568.

- ↑ Niemela, V. S.; Gamen, R. C.; Barbá, R. H.; Fernández Lajús, E.; Benaglia, P.; Solivella, G. R.; Reig, P.; Coe, M. J. (2008). "The very massive X-ray bright binary system Wack 2134 (= WR 21a)". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 389 (3): 1447. arXiv:0807.0728. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.389.1447N. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13684.x.

- ↑ Meynadier, F.; Heydari-Malayeri, M.; Walborn, N. R. (2005). "The LMC H II region N 214C and its peculiar nebular blob". Astronomy and Astrophysics 436: 117. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20042543.

- ↑ Taylor, W. D.; Evans, C. J.; Sana, H.; Walborn, N. R.; De Mink, S. E.; Stroud, V. E.; Alvarez-Candal, A.; Barbá, R. H.; Bestenlehner, J. M.; Bonanos, A. Z.; Brott, I.; Crowther, P. A.; De Koter, A.; Friedrich, K.; Gräfener, G.; Hénault-Brunet, V.; Herrero, A.; Kaper, L.; Langer, N.; Lennon, D. J.; Maíz Apellániz, J.; Markova, N.; Morrell, N.; Monaco, L.; Vink, J. S. (2011). "The VLT-FLAMES Tarantula Survey". Astronomy & Astrophysics 530: L10. arXiv:1103.5387. Bibcode:2011A&A...530L..10T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116785.

- ↑ Fang, M.; Van Boekel, R.; King, R. R.; Henning, T.; Bouwman, J.; Doi, Y.; Okamoto, Y. K.; Roccatagliata, V.; Sicilia-Aguilar, A. (2012). "Star formation and disk properties in Pismis 24". Astronomy & Astrophysics 539: A119. arXiv:1201.0833. Bibcode:2012A&A...539A.119F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015914.

- ↑ Orosz, J. A.; McClintock, J. E.; Narayan, R.; Bailyn, C. D.; Hartman, J. D.; Macri, L.; Liu, J.; Pietsch, W.; Remillard, R. A.; Shporer, A.; Mazeh, T. (2007). "A 15.65-solar-mass black hole in an eclipsing binary in the nearby spiral galaxy M 33". Nature 449 (7164): 872–875. doi:10.1038/nature06218. PMID 17943124.

- ↑ Wade, G. A.; Grunhut, J.; Gräfener, G.; Howarth, I. D.; Martins, F.; Petit, V.; Vink, J. S.; Bagnulo, S.; Folsom, C. P.; Nazé, Y.; Walborn, N. R.; Townsend, R. H. D.; Evans, C. J. (2012). "The spectral variability and magnetic field characteristics of the Of?p star HD 148937★". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 419 (3): 2459. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19897.x.

- ↑ Adriane Liermann et all (2011). "High-mass stars in the Galactic center Quintuplet cluster". Bulletin de la Societe Royale des Sciences de Liege 80: 160-164.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Bhatt, H.; Pandey, J. C.; Kumar, B.; Singh, K. P.; Sagar, R. (2010). "X-ray emission characteristics of two Wolf-Rayet binaries: V444 Cyg and CD Cru". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 402 (3): 1767. arXiv:0911.1489. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.402.1767B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15999.x.

- ↑ Niemela, V. S.; Gamen, R. C.; Barbá, R. H.; Fernández Lajús, E.; Benaglia, P.; Solivella, G. R.; Reig, P.; Coe, M. J. (2008). "The very massive X-ray bright binary system Wack 2134 (= WR 21a)". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 389 (3): 1447. arXiv:0807.0728. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.389.1447N. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13684.x.

- ↑ Vink, J. S.; Davies, B.; Harries, T. J.; Oudmaijer, R. D.; Walborn, N. R. (2009). "On the presence and absence of disks around O-type stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics 505 (2): 743. arXiv:0909.0888. Bibcode:2009A&A...505..743V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912610.

- ↑ Geballe, T. R.; Najarro, F.; Rigaut, F.; Roy, J. ‐R. (2006). "TheK‐Band Spectrum of the Hot Star in IRS 8: An Outsider in the Galactic Center?". The Astrophysical Journal 652: 370. arXiv:astro-ph/0607550. Bibcode:2006ApJ...652..370G. doi:10.1086/507764.

- ↑ Paul A Crowther; Carpano; Hadfield; Pollock (2007). "On the optical counterpart of NGC300 X-1 and the global Wolf-Rayet content of NGC300". Astronomy and Astrophysics 469 (31): L31. arXiv:0705.1544. Bibcode:2007A&A...469L..31C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077677.

- ↑ Bulik, T.; Belczynski, K.; Prestwich, A. (2011). "Ic10 X-1/ngc300 X-1: The Very Immediate Progenitors of Bh-Bh Binaries". The Astrophysical Journal 730 (2): 140. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/730/2/140.

- ↑ Chini, R.; Hoffmeister, V. H.; Nielbock, M.; Scheyda, C. M.; Steinacker, J.; Siebenmorgen, R.; Nürnberger, D. (2006). "A Remnant Disk around a Young Massive Star". The Astrophysical Journal 645: L61. doi:10.1086/505862.

- ↑ Achmad, L.; Lamers, H. J. G. L. M.; Pasquini, L. (1997). "Radiation driven wind models for A, F and G supergiants". Astronomy and Astrophysics 320: 196. Bibcode:1997A&A...320..196A.

- ↑ Moscadelli, L.; Goddi, C. (2014). "A multiple system of high-mass YSOs surrounded by disks in NGC 7538 IRS1". Astronomy & Astrophysics 566: A150. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201423420.

- ↑ Ulmer, A.; Fitzpatrick, E. L. (1998). "Revisiting the Modified Eddington Limit for Massive Stars". The Astrophysical Journal 504: 200. arXiv:astro-ph/9708264. Bibcode:1998ApJ...504..200U. doi:10.1086/306048.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||