List of Pakistani inventions and discoveries

This article lists inventions and discoveries made by scientists with Pakistani nationality within Pakistan and outside the country, as well as those made in the territorial area of what is now Pakistan prior to the independence of Pakistan in 1947.

Indus Valley civilisation

- Button, ornamental: Buttons—made from seashell—were used in the Indus Valley Civilization for ornamental purposes by 2000 BCE.[1] Some buttons were carved into geometric shapes and had holes pieced into them so that they could attached to clothing by using a thread.[1] Ian McNeil (1990) holds that: "The button, in fact, was originally used more as an ornament than as a fastening, the earliest known being found at Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley. It is made of a curved shell and about 5000 years old."[2]

- Cockfighting: Cockfighting was a pastime in the Indus Valley Civilization in what today is Pakistan by 2000 BCE[3] and one of the uses of the fighting cock. The Encyclopædia Britannica (2008)—on the origins of cockfighting—holds: "The game fowl is probably the nearest to the Indian red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus), from which all domestic chickens are believed to be descended...The sport was popular in ancient times in India, China, Persia, and other Eastern countries and was introduced into Greece in the time of Themistocles (c. 524–460 BCE). The sport spread throughout Asia Minor and Sicily. For a long time the Romans affected to despise this "Greek diversion," but they ended up adopting it so enthusiastically that the agricultural writer Columella (1st century CE) complained that its devotees often spent their whole patrimony in betting at the side of the pit."[4]

- Furnace: The earliest furnace was excavated at Balakot, a site of the Indus Valley Civilization in the Mansehra District in the Hazara Province province of Pakistan, dating back to its mature phase (c. 2500-1900 BCE). The furnace was most likely used for the manufacturing of ceramic objects.[5]

- Plough, animal-drawn: The earliest archeological evidence of an animal-drawn plough dates back to 2500 BCE in the Indus Valley Civilization in Pakistan.[6]

- Ruler: Rulers made from Ivory were in use by the Indus Valley Civilization in what today is Pakistan and some parts of Western India prior to 1500 BCE.[7] Excavations at Lothal (2400 BCE) have yielded one such ruler calibrated to about 1/16 of an inch—less than 2 millimeters.[7] Ian Whitelaw (2007) holds that 'The Mohenjo-Daro ruler is divided into units corresponding to 1.32 inches (33.5 mm) and these are marked out in decimal subdivisions with amazing accuracy—to within 0.005 of an inch. Ancient bricks found throughout the region have dimensions that correspond to these units.'[8] Shigeo Iwata (2008) further writes 'The minimum division of graduation found in the segment of an ivory-made linear measure excavated in Lothal was 1.79 mm (that corresponds to 1/940 of a fathom), while that of the fragment of a shell-made one from Mohenjo-daro was 6.72 mm (1/250 of a fathom), and that of bronze-made one from Harapa was 9.33 mm (1/180 of a fathom).'[9] The weights and measures of the Indus civilization also reached Persia and Central Asia, where they were further modified.[9]

- Stepwell: Earliest clear evidence of the origins of the stepwell is found in the Indus Valley Civilization's archaeological site at Mohenjodaro in Pakistan.[10] The three features of stepwells in the subcontinent are evident from one particular site, abandoned by 2500 BCE, which combines a bathing pool, steps leading down to water, and figures of some religious importance into one structure.[10] The early centuries immediately before the common era saw the Buddhists and the Jains of India adapt the stepwells into their architecture.[10] Both the wells and the form of ritual bathing reached other parts of the world with Buddhism.[10] Rock-cut step wells in the subcontinent date from 200-400 CE.[11] Subsequently the wells at Dhank (550-625 CE) and stepped ponds at Bhinmal (850-950 CE) were constructed.[11]

Centers of ancient learning in Pakistan

Pakistan was the seat of ancient learning and some consider Taxila to be an early university [12] [13] [14] or centre of higher education,[15] others do not consider it a university in the modern sense, [16] [17] [18] in contrast to the later Nalanda University.[18][19][20]

Takshashila is described in some detail in later Jātaka tales, written in Sri Lanka around the 5th century CE.[21] Generally, a student entered Taxila at the age of sixteen. The Vedas and the Eighteen Arts, which included skills such as archery, hunting, and elephant lore, were taught, in addition to its law school, medical school, and school of military science.[22]

Post-independence

Agriculture

- In 2013, a Pakistani firm invented a new formula to make fertilizers that cannot be converted into bomb-making materials. The firm, Fatima Fertilizer, had succeeded in making non-lethal alternatives to ammonium nitrate, a key ingredient in the fertilizers it makes. Fertilizers with ammonium nitrate, however, can easily be converted into bomb-making ingredients. This invention was praised by the Pentagon. “Such a long-term solution would be a true scientific breakthrough,” US Army Lieutenant General Michael Barbero, the head of the Pentagon’s Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization, said in a statement. After this invention, CNN reported that the United States and Pakistan reached an agreement to jointly make fertilizers with non-explosive materials. But diplomatic sources told Dawn that an agreement could only be reached after the new material is tested. The sources said that US experts would soon visit Pakistan for testing the new material with experts from the Fatima Group, Pakistan’s major fertilizer manufacturer.[23]

Biology

- Dr. Naweed Syed, a specialist in the field of biomedical engineering and member of the medicine faculty at the University of Calgary, became the first scientist who managed to "connect brain cells to a silicon chip". The discovery is a major step in the research of integrating computers with human brains to help people control artificial limbs, monitor people's vital signs, correct memory loss or impaired vision.[24]

Chemistry

- Development of the world's first workable plastic magnet at room temperature by organic chemist and polymer scientist Naveed Zaidi.[25][26][27]

Physics

- Discovery of electroweak interaction by Abdus Salam, along with two Americans Sheldon Lee Glashow and Steven Weinberg. The discovery led them to receive the Nobel Prize in Physics.[28]

- Abdus Salam who along with Steven Weinberg independently predicted the existence of a subatomic particle now called the Higgs boson, Named after a British physicist who theorized that it endowed other particles with mass.[29]

- The development of the Standard Model of particle physics by Sheldon Glashow's discovery in 1960 of a way to combine the electromagnetic and weak interactions.[30] In 1967 Steven Weinberg[31] and Abdus Salam[32] incorporated the Higgs mechanism[33][34][35] into Glashow's electroweak theory, giving it its modern form.

- Development of the SMB probe to detect heavy water leaks in nuclear power plants by Sultan Bashiruddin Mahmood[36]

Medicine

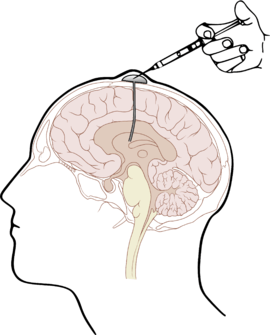

- The Ommaya reservoir - a system for the delivery of drugs (e.g. chemotherapy) into the cerebrospinal fluid for treatment of patients with brain tumours - was developed by Ayub K. Ommaya, a Pakistani neurosurgeon.[37]

- A non-invasive technology for monitoring intracranial pressure (ICP) - developed by Faisal Kashif.[38]

- Two medical devices - a pleuroperitoneal shunt and a special endotracheal tube to supply oxygen during fiberoptic bronchoscopy in awake patients - were invented by Sayed Amjad Hussain, a Pakistani American doctor from Peshawar, Pakistan. His work made him an inductee into the Medical Mission Hall of Fame.[39][40]

- A non-kink catheter mount was designed by a Pakistani doctor A. K. Jamil.[41][42] He also developed a simple device for teaching controlled ventilation (A device through which young doctors can be trained on artificial[43] ventilation of the lungs without Operation theater and patient)

Computing

- A boot sector computer virus dubbed (c)Brain, one of the first computer viruses in history,[44] was created in 1986 by the Farooq Alvi Brothers in Lahore, Pakistan, reportedly to deter piracy of the software they had written.[45][46]

- A Software simulation based on blast forensics designed by Pakistani computer scientist, Zeeshan-ul-Hassan Usmani, that can reduce deaths by 12 per cent and injuries by seven per cent on average just by changing the way a crowd of people stand near an expected suicide bomber.[47]

Music

- The Sagar Veena, a string instrument designed for use in classical music, was developed entirely in Pakistan over the last 40 years at the Sanjannagar Institute in Lahore by Raza Kazim.[48][49]

Economics

- The Human Development Index was devised by Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq in 1990 and had the explicit purpose "to shift the focus of development economics from national income accounting to people centered policies".[50][51]

Technology

- A team headed by Professor Sohail Khan, a Pakistani researcher at Loughborough University designed a clever lavatory that transforms human waste into biological charcoal and minerals. These can then be used as fuel or a form of conditioner for soil. It also produces clean water.[52] The invention can lead to community-led total sanitation in the developing world. The challenge was set by Microsoft founder Bill Gates who wanted to improve sanitation for the poor and combat open defacation in countries where water supply and sewage pipe infrastructure is not widely available.[53]

See also

- Category:Pakistani inventors

- Science and technology in Pakistan

- List of inventions and discoveries of the Indus Valley Civilization covers the Bronze Age culture that flourished from 3300–1300 BCE in what is now Pakistan

- List of Indian inventions and discoveries covers inventions made in the Indian subcontinent between the decline of the IVC and the formation of Pakistan

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hesse, Rayner W. & Hesse (Jr.), Rayner W. (2007). Jewelrymaking Through History: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. 35. ISBN 0-313-33507-9.

- ↑ McNeil, Ian (1990). An encyclopaedia of the history of technology. Taylor & Francis. 852. ISBN 0-415-01306-2.

- ↑ Sherman, David M. (2002). Tending Animals in the Global Village. Blackwell Publishing. 46. ISBN 0-683-18051-7.

- ↑ Cockfighting. Encyclopædia Britannica 2008

- ↑ Dales (1974)

- ↑ Lal, R. (August 2001). "Thematic evolution of ISTRO: transition in scientific issues and research focus from 1955 to 2000". Soil and Tillage Research 61 (1-2): 3–12 [3]. doi:10.1016/S0167-1987(01)00184-2.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Whitelaw, page 14

- ↑ Whitelaw, page 15

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Iwata, 2254

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Livingston & Beach, 20

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Livingston & Beach, page xxiii

- ↑ Radha Kumud Mookerji (2nd ed. 1951; reprint 1989), ''Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist (p. 478), Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 81-208-0423-6:

"Thus the various centres of learning in different parts of the country became affiliated, as it were, to the educational centre, or the central university, of Taxila which exercised a kind of intellectual suzerainty over the wide world of letters in India."

- ↑ Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund (2004), A History of India, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-32919-1:

"In the early centuries the centre of Buddhist scholarship was the University of Taxila".

- ↑ Balakrishnan Muniapan, Junaid M. Shaikh (2007), "Lessons in corporate governance from Kautilya's Arthashastra in ancient India", World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 3 (1):

"Kautilya was also a Professor of Politics and Economics at Taxila University. Taxila University is one of the oldest known universities in the world and it was the chief learning centre in ancient India."

- ↑ Radha Kumud Mookerji (2nd ed. 1951; reprint 1989), Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist (p. 479), Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 81-208-0423-6:

"This shows that Taxila was a seat not of elementary, but higher, education, of colleges or a university as distinguished from schools."

- ↑ Anant Sadashiv Altekar (1934; reprint 1965), Education in Ancient India, Sixth Edition, Revised & Enlarged, Nand Kishore & Bros, Varanasi:

"It may be observed at the outset that Taxila did not possess any colleges or university in the modern sense of the term."

- ↑ F. W. Thomas (1944), in John Marshall (1951; 1975 reprint), Taxila, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi:

"We come across several Jātaka stories about the students and teachers of Takshaśilā, but not a single episode even remotely suggests that the different 'world renowned' teachers living in that city belonged to a particular college or university of the modern type."

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Taxila (2007), Encyclopædia Britannica:

"Taxila, besides being a provincial seat, was also a centre of learning. It was not a university town with lecture halls and residential quarters, such as have been found at Nalanda in the Indian state of Bihar."

- ↑ "Nalanda" (2007). Encarta.

- ↑ "Nalanda" (2001). Columbia Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Marshall 1975:81

- ↑ Radha Kumud Mookerji (2nd ed. 1951; reprint 1989). Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist (p. 478-489). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 81-208-0423-6.

- ↑ http://dawn.com/2013/03/01/pakistani-firm-makes-ied-proof-fertiliser/

- ↑ University of Calgary: Naweed Syed

- ↑ CERN courier: New polymer enables room-temperature plastic magnet

- ↑ New Scientist: First practical plastic magnets created

- ↑ Bio: Dr. Naveed Zaidi

- ↑ "Abdus Salam - Biography". Nobelprize.org. 1996-11-21. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ↑ "Pakistan shuns physicist linked to 'God particle'". Fox News. Retrieved 2012-07-09.

- ↑ S.L. Glashow (1961). "Partial-symmetries of weak interactions". Nuclear Physics 22 (4): 579–588. Bibcode:1961NucPh..22..579G. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(61)90469-2.

- ↑ S. Weinberg (1967). "A Model of Leptons". Physical Review Letters 19 (21): 1264–1266. Bibcode:1967PhRvL..19.1264W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.19.1264.

- ↑ A. Salam (1968). N. Svartholm, ed. Elementary Particle Physics: Relativistic Groups and Analyticity. Eighth Nobel Symposium. Stockholm: Almquvist and Wiksell. p. 367.

- ↑ F. Englert, R. Brout (1964). "Broken Symmetry and the Mass of Gauge Vector Mesons". Physical Review Letters 13 (9): 321–323. Bibcode:1964PhRvL..13..321E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.321.

- ↑ P.W. Higgs (1964). "Broken Symmetries and the Masses of Gauge Bosons". Physical Review Letters 13 (16): 508–509. Bibcode:1964PhRvL..13..508H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.508.

- ↑ G.S. Guralnik, C.R. Hagen, T.W.B. Kibble (1964). "Global Conservation Laws and Massless Particles". Physical Review Letters 13 (20): 585–587. Bibcode:1964PhRvL..13..585G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.585.

- ↑ "Darulhikmat". Darulhikmat. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ↑ "The Wisdom Fund Board Member Ayub Khan Ommaya, Leading Neurosurgeon and Inventor, Dead at 78". Twf.org. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ↑ DAWN.COM Suhail Yusuf October 21, 2011 (2011-10-21). "New neurological test by a Pakistani | Sci-tech". Dawn.Com. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ↑ "Illustrious Pakistani doctor inducted into Medical Hall of Fame". Express Tribune. 15 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ "About Dr. S. Amjad Hussain". University of Toledo. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ "NON-KINK CATHETER MOUNT". Br. J. Anaesth. 46 (8): 628. 1974. doi:10.1093/bja/46.8.628-a. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ↑ "A. T. M. Jamil". Academic.research.microsoft.com. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ↑ JAMIL, A. K. (1 September 1974). "A simple device for teaching controlled ventilation". Anaesthesia 29 (5): 605–606. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1974.tb00729.x. PMID 4433022. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Boot sector virus repair". Antivirus.about.com. 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ↑ "Amjad Farooq Alvi Inventor of first PC Virus post by Zagham". YouTube. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ↑ Krish, Aahan (2011-03-16). "25 Famous Computer Viruses Of All Time [INFOGRAPHIC]". Ry.com. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ↑ Siddiqui, Salman. "Learning from suicide blasts – The Express Tribune". Tribune.com.pk. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ↑ "‘Hor Vi Neevan Ho’ goes on air!". nooriworld.net. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ↑ "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India - The Tribune Lifestyle". Tribuneindia.com. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ↑ Haq, Mahbub ul. 1995. Reflections on Human Development. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ JSTOR 4407121

- ↑ Riaz Haq (2012-08-17). "Haq's Musings: British Pakistani Wins "Reinvent the Toilet Challenge"". Riazhaq.com. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ↑ Peter Popham (2012-08-16). "First he reinvented computers, now Bill Gates wants to reinvent the toilet - Health News - Health & Families". The Independent. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

External links

- applications: Can we invent more than herbal crack cream?, The Express Tribune

| ||||||||||||||