List of Dutch inventions and discoveries

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Netherlands |

|

|

| Netherlands portal |

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

The Netherlands, despite its comparatively modest size and population, had a considerable part in the making of the modern society.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] The Netherlands[8] and its people have made numerous seminal contributions to the world's civilization,[9][10][11][12][13][14][15] especially in art,[16][7][17][18][19] science,[20][21][22][23] technology and engineering,[24][25][26] economics and finance,[27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36] cartography and geography,[37][38] exploration and navigation,[39][40] law and jurisprudence,[41] thought and philosophy,[6][42][43][44] medicine,[45] and agriculture.

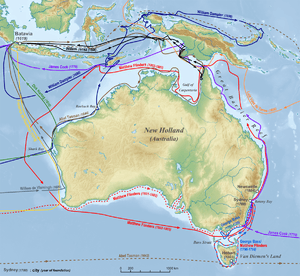

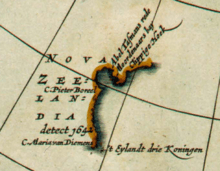

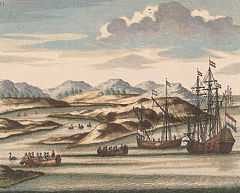

During the Age of Discovery, the Dutch built seagoing ships and traveled to the far corners of the world, leaving their language embedded in the names of places they visited.[46] Dutch exploratory voyages revealed vast new territories to the civilized world. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Dutch-speaking cartographers[47] helped lay the foundations for the birth and development of modern cartography (including nautical cartography and stellar cartography). The Dutch came to dominate the map making and map printing industry by virtue of their own travels, trade ventures, and widespread commercial networks.[48] The Dutch initiated what we would call today the free flow of geographical information. As Dutch ships reached into the unknown corners of the globe, Dutch cartographers incorporated new discoveries into their work. Instead of using the information themselves secretly, they published it, so the maps multiplied freely. They were able to share their discoveries and ideas with the world because Dutch officials supported the freedom of press. The Dutch were the first (non-natives) to undisputedly discover, explore and map many unknown isolated areas of the world such as Svalbard, Australia,[49] New Zealand, Tonga, Sakhalin,[50] and Easter Island. In many cases the Dutch were the first Europeans the natives would encounter.[51] Australia (originally known as New Holland), never became a permanent Dutch settlement, yet the Dutch were the first to undisputedly map its coastline. The Dutch navigators charted almost three-quarters of the Australian coastline, except the east coast. During the Age of Exploration, the Dutch explorers and cartographers were also the first to systematically observe and map (chart) the largely unknown far sounthern skies – the first significant addition to the topography of the sky since Ptolemy's time. Among the IAU's 88 modern constellations, there are 15 Dutch-created constellations, including 12 southern constellations.[52][53] In the sixth episode Travellers' Tales of the popular documentary TV series Cosmos (1980), American astronomer Carl Sagan, who also served as host, took a look at the Voyager missions to Jupiter and Saturn, and compared the excitement to the adventuring spirit of the early Dutch explorers who traveled unknown seas for the first time. Their discoveries led to further knowledge of previously unheard of wonders and riches, comparable to the invaluable data retrieved by the spacecraft.

Dutch-speaking people, in spite of their relatively small number, have a significant history of invention, innovation, discovery and exploration. The following list is composed of objects, (largely) unknown lands, breakthrough ideas/concepts, principles, phenomena, processes, methods, techniques, styles etc., that were discovered or invented (or pioneered) by people from the Netherlands and Dutch-speaking people from the former Southern Netherlands (Zuid-Nederlanders in Dutch). Until the fall of Antwerp (1585), the Dutch and Flemish were generally seen as one people.[54]

Inventions and innovations

Arts and architecture

Movements and styles

De Stijl (Neo-Plasticism) (1917)

The De Stijl school proposed simplicity and abstraction, both in architecture and painting, by using only straight horizontal and vertical lines and rectangular forms. Furthermore, their formal vocabulary was limited to the primary colours, red, yellow, and blue and the three primary values, black, white and grey. De Stijl's principal members were painters Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931), Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), Vilmos Huszár (1884–1960), and Bart van der Leck (1876–1958) and architects Gerrit Rietveld (1888–1964), Robert van 't Hoff (1888–1979) and J.J.P. Oud (1890–1963).

Architecture

Brabantine Gothic architecture (1300s)

Brabantine Gothic, occasionally called Brabantian Gothic, is a significant variant of Gothic architecture that is typical for the Low Countries. It surfaced in the first half of the 14th century at Saint Rumbold's Cathedral in the City of Mechelen. The Brabantine Gothic style originated with the advent of the Duchy of Brabant and spread across the Burgundian Netherlands.

Netherlandish gabled architecture (1400s-1600s)

.jpg)

The Dutch gable was a notable feature of the Dutch-Flemish Renaissance architecture (or Northern Mannerist architecture) that spread to northern Europe from the Low Countries, arriving in Britain during the latter part of the 16th century. Notable castles/buildings including Frederiksborg Castle, Rosenborg Castle, Kronborg Castle, Børsen, Riga's House of the Blackheads and Gdańsk's Green Gate were built in Dutch-Flemish Renaissance style with sweeping gables, sandstone decorations and copper-covered roofs. Later Dutch gables with flowing curves became absorbed into Baroque architecture. Examples of Dutch-gabled buildings can be found in historic cities across Europe such as Potsdam (Dutch Quarter), Friedrichstadt, Gdańsk and Gothenburg. The style spread beyond Europe, for example Barbados is well known for Dutch gables on its historic buildings. Dutch settlers in South Africa brought with them building styles from the Netherlands: Dutch gables, then adjusted to the Western Cape region where the style became known as Cape Dutch architecture. In the Americas and Northern Europe, the West End Collegiate Church (New York City, 1892), the Chicago Varnish Company Building (Chicago, 1895), Pont Street Dutch-style buildings (London, 1800s), Helsingør Station (Helsingør, 1891), and Gdańsk University of Technology's Main Building (Gdańsk, 1904) are typical examples of the Dutch Renaissance Revival (Neo-Renaissance) architecture in the late 19th century.

Netherlandish Mannerist architecture (Antwerp Mannerism) (1500s)

Antwerp Mannerism is the name given to the style of a largely anonymous group of painters from Antwerp in the beginning of the 16th century. The style bore no direct relation to Renaissance or Italian Mannerism, but the name suggests a peculiarity that was a reaction to the classic style of the early Netherlandish painting. Antwerp Mannerism may also be used to describe the style of architecture, which is loosely Mannerist, developed in Antwerp by about 1540, which was then influential all over Northern Europe. The Green Gate (Brama Zielona) in Gdańsk, Poland, is a building which is inspired by the Antwerp City Hall. It was built between 1568 and 1571 by Regnier van Amsterdam and Hans Kramer to serve as the formal residence of the Polish monarchs when visiting Gdańsk.

Cape Dutch architecture (1650s)

Cape Dutch architecture is an architectural style found in the Western Cape of South Africa. The style was prominent in the early days (17th century) of the Cape Colony, and the name derives from the fact that the initial settlers of the Cape were primarily Dutch. The style has roots in medieval Netherlands, Germany, France and Indonesia. Houses in this style have a distinctive and recognisable design, with a prominent feature being the grand, ornately rounded gables, reminiscent of features in townhouses of Amsterdam built in the Dutch style.

Amsterdam School (Dutch Expressionist architecture) (1910s)

The Amsterdam School (Dutch: Amsterdamse School) flourished from 1910 through about 1930 in the Netherlands. The Amsterdam School movement is part of international Expressionist architecture, sometimes linked to German Brick Expressionism.

Rietveld Schröder House (De Stijl architecture) (1924)

The Rietveld Schröder House or Schröder House (Rietveld Schröderhuis in Dutch) in Utrecht was built in 1924 by Dutch architect Gerrit Rietveld. It became a listed monument in 1976 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000. The Rietveld Schröder House constitutes both inside and outside a radical break with tradition, offering little distinction between interior and exterior space. The rectilinear lines and planes flow from outside to inside, with the same colour palette and surfaces. Inside is a dynamic, changeable open zone rather than a static accumulation of rooms. The house is one of the best known examples of De Stijl architecture and arguably the only true De Stijl building.[55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66]

Van Nelle Factory (1925–1931)

The Van Nelle factory was built between 1925 and 1931. Its most striking feature is its huge glass façades. The factory was designed on the premise that a modern, transparent and healthy working environment in green surroundings would be good both for production and for workers' welfare. The complex is the result of the radical application of a number of cultural and technical concepts dating from the early twentieth century. This led to a new, functional approach to architecture that enjoyed mass appeal right from the start. The factory had a huge impact on the development of modern architecture in Europe and elsewhere. However, it is not just its architectural style, but rather its response to the social challenges of the day which makes the Van Nelle factory special. Its glass façade, with its large openable windows and advanced ventilation system, is quite unique, even though similar factories are to be found elsewhere.[67] The Van Nelle Factory is a Dutch national monument (Rijksmonument) and since 2014 has the status of UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Justification of Outstanding Universal Value was presented in 2013 to the UNESCO World Heritage Committee.

The factory complex, a collection of interconnected buildings, is one of the highlights of twentieth-century industrial architecture. Soon after it was built, prominent architects described the factory as ‘the most beautiful spectacle of our modern age that I know’ (Le Corbusier, 1932) and ‘a poem in steel and glass’ (Robertson and Yerbury, 1930).[68][69][70] A delicate grid of glass and concrete, the two parts of the Van Nelle complex are connected by dynamic, angular bridges. It influenced factory design worldwide and now houses creative industries and art fairs.[71][72]

Furniture

Dutch door (1600s)

The Dutch door (also known as stable door or half door) is a type of door divided horizontally in such a fashion that the bottom half may remain shut while the top half opens. The initial purpose of this door was to keep animals out of farmhouses, while keeping children inside, yet allowing light and air to filter through the open top. This type of door was common in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century and appears in Dutch paintings of the period. They were commonly found in Dutch areas of New York and New Jersey (before the American Revolution) and in South Africa.[73]

Red and Blue Chair (1917)

The Red and Blue Chair was designed in 1917 by Gerrit Rietveld. It represents one of the first explorations by the De Stijl art movement in three dimensions. It features several Rietveld joints.

Zig-Zag Chair (1934)

The Zig-Zag Chair was designed by Rietveld in 1934. It is a minimalist design without legs, made by 4 flat wooden tiles that are merged in a Z-shape using Dovetail joints. It was designed for the Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht.

Visual arts

Foundations of modern oil painting (1400s)

Although oil paint was first used for Buddhist paintings by Indian and Chinese painters sometime between the fifth and tenth centuries, it did not gain notoriety until the 15th century. Its practice may have migrated westward during the Middle Ages. Oil paint eventually became the principal medium used for creating artworks as its advantages became widely known. The transition began with Early Netherlandish painting in northern Europe, and by the height of the Renaissance oil painting techniques had almost completely replaced tempera paints in the majority of Europe. Early Netherlandish painting (Jan van Eyck in particular) in the 15th century was the first to make oil the default painting medium, and to explore the use of layers and glazes, followed by the rest of Northern Europe, and only then Italy.[74][75][76][77] Early works were still panel paintings on wood, but around the end of the 15th century canvas became more popular, as it was cheaper, easier to transport, and allowed larger works.

Proto-Realism (1400s–1600s)

Two aspects of realism were rooted in at least two centuries of Dutch tradition: conspicuous textural imitation and a penchant for ordinary and exaggeratedly comic scenes. Two hundred years before the rise of literary realism, Dutch painters had already made an art of the everyday – pictures that served as a compelling model for the later novelists. By the mid-1800s, 17th-century Dutch painting figured virtually everywhere in the British and French fiction we esteem today as the vanguard of realism.

Proto-Surrealism (1470s–1510s)

Hieronymus Bosch is considered one of the prime examples of Pre-Surrealism. The surrealists relied most on his insights. In the 20th century, Bosch's paintings (e.g. The Garden of Earthly Delights, The Haywain, The Temptation of St. Anthony and The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things) were cited by the Surrealists as precursors to their own visions.

Modern still-life painting (1500s–1600s)

Still-life painting as an independent genre or specialty first flourished in the Netherlands in the last quarter of the 16th century, and the English term derives from stilleven: still life, which is a calque, while Romance languages (as well as Greek, Polish, Russian and Turkish) tend to use terms meaning dead nature.

Naturalistic landscape painting (1500s–1600s)

The term "landscape" derives from the Dutch word landschap, which originally meant "region, tract of land" but acquired the artistic connotation, "a picture depicting scenery on land" in the early 1500s. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the tradition of depicting pure landscapes declined and the landscape was seen only as a setting for religious and figural scenes. This tradition continued until the 16th century when artists began to view the landscape as a subject in its own right. The Dutch Golden Age painting of the 17th century saw the dramatic growth of landscape painting, in which many artists specialized, and the development of extremely subtle realist techniques for depicting light and weather.

Genre painting (1500s)

The Flemish Renaissance painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder chose peasants and their activities as the subject of many paintings. Genre painting flourished in Northern Europe in his wake. Adriaen van Ostade, David Teniers, Aelbert Cuyp, Jan Steen, Johannes Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch were among many painters specializing in genre subjects in the Netherlands during the 17th century. The generally small scale of these artists' paintings was appropriate for their display in the homes of middle class purchasers.

Marine painting (1600s)

Marine painting began in keeping with medieval Christian art tradition. Such works portrayed the sea only from a bird's eye view, and everything, even the waves, was organized and symmetrical. The viewpoint, symmetry and overall order of these early paintings underlined the organization of the heavenly cosmos from which the earth was viewed. Later Dutch artists such as Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom, Cornelius Claesz, Abraham Storck, Jan Porcellis, Simon de Vlieger, Willem van de Velde the Elder, Willem van de Velde the Younger and Ludolf Bakhuizen developed new methods for painting, often from a horizontal point of view, with a lower horizon and more focus on realism than symmetry.[78][79]

Vanitas (1600s)

The term vanitas is most often associated with still life paintings that were popular in seventeenth-century Dutch art, produced by the artists such as Pieter Claesz. Common vanitas symbols included skulls (a reminder of the certainty of death); rotten fruit (decay); bubbles, (brevity of life and suddenness of death); smoke, watches, and hourglasses, (the brevity of life); and musical instruments (the brevity and ephemeral nature of life). Fruit, flowers and butterflies can be interpreted in the same way, while a peeled lemon, as well as the typical accompanying seafood was, like life, visually attractive but with a bitter flavor.

Civil group portraiture (1600s)

Group portraits were produced in great numbers during the Baroque period, particularly in the Netherlands. Unlike in the rest of Europe, Dutch artists received no commissions from the Calvinist Church which had forbidden such images or from the aristocracy which was virtually non-existent. Instead, commissions came from civic and businesses associations. Dutch painter Frans Hals used fluid brush strokes of vivid color to enliven his group portraits, including those of the civil guard to which he belonged. Rembrandt benefitted greatly from such commissions and from the general appreciation of art by bourgeois clients, who supported portraiture as well as still-life and landscape painting. Notably, the world's first significant art and dealer markets flourished in Holland at that time.

Tronie (1600s)

In the 17th century, Dutch painters (especially Frans Hals, Rembrandt, Jan Lievens and Johannes Vermeer) began to create uncommissioned paintings called tronies that focused on the features and/or expressions of people who were not intended to be identifiable. They were conceived more for art's sake than to satisfy conventions. The tronie was a distinctive type of painting, combining elements of the portrait, history, and genre painting. This was usually a half-length of a single figure which concentrated on capturing an unusual mood or expression. The actual identity of the model was not supposed to be important, but they might represent a historical figure and be in exotic or historic costume. In contrast to portraits, "tronies" were painted for the open market. They differ from figurative paintings and religious figures in that they are not restricted to a moral or narrative context. It is, rather, much more an exploration of the spectrum of human physiognomy and expression and the reflection of conceptions of character that are intrinsic to psychology’s pre-history.

Rembrandt lighting (1600s)

Rembrandt lighting is a lighting technique that is used in studio portrait photography. It can be achieved using one light and a reflector, or two lights, and is popular because it is capable of producing images which appear both natural and compelling with a minimum of equipment. Rembrandt lighting is characterized by an illuminated triangle under the eye of the subject, on the less illuminated side of the face. It is named for the Dutch painter Rembrandt, who often used this type of lighting in his portrait paintings.

Pronkstilleven (1650s)

Pronkstilleven (pronk still life or ostentatious still life) is a type of banquet piece whose distinguishing feature is a quality of ostentation and splendor. These still lifes usually depict one or more especially precious objects. Although the term is a post-17th century invention, this type is characteristic of the second half of the seventeenth century. It was developed in the 1640s in Antwerp from where it spread quickly to the Dutch Republic. Flemish artists such as Frans Snyders and Adriaen van Utrecht started to paint still lifes that emphasized abundance by depicting a diversity of objects, fruits, flowers and dead game, often together with living people and animals. The style was soon adopted by artists from the Dutch Republic.[80] A leading Dutch representative was Jan Davidsz. de Heem, who spent a long period of his active career in Antwerp and was one of the founders of the style in Holland.[81] [82] Other leading representatives in the Dutch Republic were Abraham van Beyeren, Willem Claeszoon Heda and Willem Kalf.[80]

Proto-Expressionism (1880s)

Vincent van Gogh's work is most often associated with Post-Impressionism, but his innovative style had a vast influence on 20th-century art and established what would later be known as Expressionism, also greatly influencing fauvism and early abstractionism. His impact on German and Austrian Expressionists was especially profound. "Van Gogh was father to us all," the German Expressionist painter Max Pechstein proclaimed in 1901, when Van Gogh's vibrant oils were first shown in Germany and triggered the artistic reformation, a decade after his suicide in obscurity in France. In his final letter to Theo, Van Gogh stated that, as he did not have any children, he viewed his paintings as his progeny. Reflecting on this, the British art historian Simon Schama concluded that he "did have a child of course, Expressionism, and many, many heirs."

M. C. Escher's graphic arts (1920s–1960s)

Dutch graphic artist Maurits Cornelis Escher, usually referred to as M. C. Escher, is known for his often mathematically inspired woodcuts, lithographs, and mezzotints. These feature impossible constructions, explorations of infinity, architecture and tessellations. His special way of thinking and rich graphic work has had a continuous influence in science and art, as well as permeating popular culture. His ideas have been used in fields as diverse as psychology, philosophy, logic, crystallography and topology. His art is based on mathematical principles like tessellations, spherical geometry, the Möbius strip, unusual perspectives, visual paradoxes and illusions, different kinds of symmetries and impossible objects. Gödel, Escher, Bach by Douglas Hofstadter discusses the ideas of self-reference and strange loops, drawing on a wide range of artistic and scientific work, including Escher's art and the music of J. S. Bach, to illustrate ideas behind Gödel's incompleteness theorems.

Miffy (Nijntje) (1955)

Miffy (Nijntje) is a small female rabbit in a series of picture books drawn and written by Dutch artist Dick Bruna.

Agriculture

Holstein Friesian cattle (100s BC)

Holsteins or Holstein-Friesians are a breed of cattle known today as the world's highest-production dairy animals. Originating in Europe, Holstein-Friesians were bred in the two north Holland provinces of North Holland and Friesland, and Schleswig-Holstein in what became Germany. The animals were the regional cattle of the Frisians and the Saxons. The Dutch breeders bred and oversaw the development of the breed with the goal of obtaining animals that could best use grass, the area's most abundant resource. Its color pattern came from artificial selection by the breeders.[83] The origins of the breed can be traced to the black cows and white cows of the Batavians and Frisians - migrant tribes who settled the coastal Rhine region more than two thousand years ago. Over time, these two kinds of cows were selectively bred together with the aim of developing an animal that would make the best use of limited land by yielding generous quantities of both milk and meat. The result was the efficient, high-producing black-and-white dairy cow we know today as the Holstein Friesian.

Brussels sprout (1200s)

Forerunners to modern Brussels sprouts were likely cultivated in ancient Rome. Brussels sprouts as we now know them were grown possibly as early as the 13th century in the Low Countries (may have originated in Brussels). The first written reference dates to 1587. During the 16th century, they enjoyed a popularity in the Southern Netherlands that eventually spread throughout the cooler parts of Northern Europe.

Orange-coloured carrot (1500s)

Through history, carrots weren’t always orange. They were black, purple, white, brown, red and yellow. Probably orange too, but this was not the dominant colour. Orange-coloured carrots appeared in the Netherlands in the 16th century.[84] Dutch farmers in Hoorn bred the color. They succeeded by cross-breeding pale yellow with red carrots. It is more likely that Dutch horticulturists actually found an orange rooted mutant variety and then worked on its development through selective breeding to make the plant consistent. Through successive hybridisation the orange colour intensified. Improved strains resulted in three main varieties red, yellow and deep gold. This was developed to become the dominant species across the world, a sweet orange. Before the Dutch bred the sweet, orange-coloured carrot, the carrot had a less sweet (bitter) taste than the ones we know today. The colour choice may have been made to gain favour with the House of Orange, who led the Dutch Revolt against the Spanish Empire and later became the Dutch Royal family.[85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96] Beta-Carotene, found in orange carrots is converted into vitamin A in the body by all animals except cats.

Belle de Boskoop (apple) (1856)

Belle de Boskoop is an apple cultivar which, as its name suggests, originated in Boskoop, where it began as a chance seedling in 1856. There are many variants: Boskoop red, yellow or green. This rustic apple is firm, tart and fragrant. Greenish-gray tinged with red, the apple stands up well to cooking. Generally Boskoop varieties are very high in acid content and can contain more than four times the vitamin C of 'Granny Smith' or 'Golden Delicious'.[97]

Karmijn de Sonnaville (apple) (1949)

Karmijn de Sonnaville is a variety of apple bred by Piet de Sonnaville, working in Wageningen in 1949. It is a cross of Cox's Orange Pippin and Jonathan, and was first grown commercially beginning in 1971. It is high both in sugars (including some sucrose) and acidity. It is a triploid, and hence needs good pollination, and can be difficult to grow. It also suffers from fruit russet, which can be severe. In Manhart’s book, “apples for the 21st century”, Karmijn de Sonnaville is tipped as a possible success for the future. Karmijn de Sonnaville is not widely grown in large quantities, but in Ireland, at The Apple Farm, 8 acres (32,000 m2) it is grown for fresh sale and juice-making, for which the variety is well suited.

Elstar (apple) (1950s)

Elstar apple is an apple cultivar that was first developed in the Netherlands in the 1950s by crossing Golden Delicious and Ingrid Marie apples. It quickly became popular, especially in Europe and was first introduced to America in 1972.[98] It remains popular in Continental Europe. The Elstar is a medium-sized apple whose skin is mostly red with yellow showing. The flesh is white, and has a soft, crispy texture. It may be used for cooking and is especially good for making apple sauce. In general, however, it is used in desserts due to its sweet flavour.

Groasis Waterboxx (2010)

The Groasis Waterboxx is a device designed to help grow trees in dry areas. It was developed by former flower exporter Pieter Hoff, and won Popular Science's "Green Tech Best of What's New" Innovation of the year award for 2010.

Biology

Tinbergen's four questions (1963)

Tinbergen's four questions, named after Nikolaas Tinbergen (one of the founders of modern ethology), are complementary categories of explanations for behavior. He suggested that an integrative understanding of behavior must include both a proximate and ultimate (functional) analysis of behavior, as well as an understanding of both phylogenetic/developmental history and the operation of current mechanisms.

Cartography and geography

Method for determining longitude using a clock (1530)

The Dutch-Frisian geographer Gemma Frisius was the first to propose the use of a chronometer to determine longitude in 1530. In his book On the Principles of Astronomy and Cosmography (1530), Frisius explains for the first time how to use a very accurate clock to determine longitude.[99] The problem was that in Frisius’ day, no clock was sufficiently precise to use his method. In 1761, the British clock-builder John Harrison constructed the first marine chronometer, which allowed the method developed by Frisius.

Triangulation as a surveying method (foundations of modern surveying) (1533 & 1615)

Triangulation had first emerged as a map-making method in the mid sixteenth century when the Dutch-Frisian mathematician Gemma Frisius set out the idea in his Libellus de locorum describendorum ratione (Booklet concerning a way of describing places).[100][101][102][103][104][105] Dutch cartographer Jacob van Deventer was among the first to make systematic use of triangulation, the technique whose theory was described by Gemma Frisius in his 1533 book.

The modern systematic use of triangulation networks stems from the work of the Dutch mathematician Willebrord Snell (born Willebrord Snel van Royen), who in 1615 surveyed the distance from Alkmaar to Bergen op Zoom, approximately 70 miles (110 kilometres), using a chain of quadrangles containing 33 triangles in all.[106][107][108] The two towns were separated by one degree on the meridian, so from his measurement he was able to calculate a value for the circumference of the earth – a feat celebrated in the title of his book Eratosthenes Batavus (The Dutch Eratosthenes), published in 1617. Snell's methods were taken up by Jean Picard who in 1669–70 surveyed one degree of latitude along the Paris Meridian using a chain of thirteen triangles stretching north from Paris to the clocktower of Sourdon, near Amiens.

Mercator projection (1569)

The Mercator projection is a cylindrical map projection presented by the Flemish geographer and cartographer Gerardus Mercator in 1569. It became the standard map projection for nautical purposes because of its ability to represent lines of constant course, known as rhumb lines or loxodromes, as straight segments which conserve the angles with the meridians.[109]

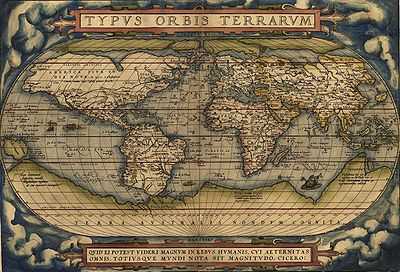

First true (modern) atlas (1570)

Flemish geographer and cartographer Abraham Ortelius generally recognized as the creator of the world's first modern atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World). Ortelius's Theatrum Orbis Terrarum is considered the first true atlas in the modern sense: a collection of uniform map sheets and sustaining text bound to form a book for which copper printing plates were specifically engraved. It is sometimes referred to as the summary of sixteenth-century cartography.[110][111][112][113]

First printed atlas of nautical charts (1584)

The first printed atlas of nautical charts (De Spieghel der Zeevaerdt or The Mirror of Navigation / The Mariner's Mirror) was produced by Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer in Leiden. This atlas was the first attempt to systematically codify nautical maps. This chart-book combined an atlas of nautical charts and sailing directions with instructions for navigation on the western and north-western coastal waters of Europe. It was the first of its kind in the history of maritime cartography, and was an immediate success. The English translation of Waghenaer's work was published in 1588 and became so popular that any volume of sea charts soon became known as a "waggoner", the Anglicized form of Waghenaer's surname.[114][115][116][117][118][119][120]

Concept of atlas (1595)

Gerardus Mercator was the first to coin the word atlas to describe a bound collection of maps through his own collection entitled "Atlas sive Cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mvndi et fabricati figvra". He coined this name after the Greek god who held the earth in his arms.[113][121]

First systematic charting of the far southern skies (southern constellations) (1595-97)

In the golden age of Dutch cartography and exploration (approximately 1570–1722), the Dutch-speaking peoples made the seminal contributions to the natural history, cartography, geography and ethnography. Flanders-based cartographers such as Gerardus Mercator and Abraham Ortelius helped lay the foundations for the modern cartography. In the area of celestial cartography, the Dutch Republic's explorers and cartographers like Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser, Frederick de Houtman, Petrus Plancius and Jodocus Hondius were the pioneers in first systematic charting/mapping of largely unknown southern hemisphere skies in the late 16th century.

The constellations around the South Pole were not observable from north of the equator, by Babylonians, Greeks, Chinese or Arabs. The modern constellations in this region were defined during the Age of Exploration, notably by Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman at the end of sixteenth century. These twelve Dutch-created southern constellations represented flora and fauna of the East Indies and Madagascar. They were depicted by Johann Bayer in his star atlas Uranometria of 1603.[122] Several more were created by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in his star catalogue, published in 1756.[123] By the end of the Ming Dynasty, Xu Guangqi introduced 23 asterisms of the southern sky based on the knowledge of western star charts.[124] These asterisms have since been incorporated into the traditional Chinese star maps. Among the IAU's 88 modern constellations, there are 15 Dutch-created constellations (including Apus, Camelopardalis, Chamaeleon, Columba, Dorado, Grus, Hydrus, Indus, Monoceros, Musca, Pavo, Phoenix, Triangulum Australe, Tucana and Volans).

Continental drift hypothesis (1596)

The speculation that continents might have 'drifted' was first put forward by Abraham Ortelius in 1596. The concept was independently and more fully developed by Alfred Wegener in 1912. Because Wegener's publications were widely available in German and English and because he adduced geological support for the idea, he is credited by most geologists as the first to recognize the possibility of continental drift. During the 1960s geophysical and geological evidence for seafloor spreading at mid-oceanic ridges established continental drift as the standard theory or continental origin and an ongoing global mechanism.

Chemicals and materials

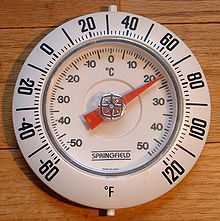

Bow dye (1630)

While making a coloured liquid for a thermometer, Cornelis Drebbel dropped a flask of Aqua regia on a tin window sill, and discovered that stannous chloride makes the color of carmine much brighter and more durable. Though Drebbel himself never made much from his work, his daughters Anna and Catharina and his sons-in-law Abraham and Johannes Sibertus Kuffler set up a successful dye works. One was set up in 1643 in Bow, London, and the resulting color was called bow dye.

Dyneema (1979)

Dutch chemical company DSM invented and patented the Dyneema in 1979. Dyneema fibres have been in commercial production since 1990 at their plant at Heerlen. These fibers are manufactured by means of a gel-spinning process that combines extreme strength with incredible softness. Dyneema fibres, based on ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE), is used in many applications in markets such as life protection, shipping, fishing, offshore, sailing, medical and textiles.

Communication and multimedia

Compact cassette (1962)

In 1962 Philips invented the compact audio cassette medium for audio storage, introducing it in Europe in August 1963 (at the Berlin Radio Show) and in the United States (under the Norelco brand) in November 1964, with the trademark name Compact Cassette.[125][126][127][128][129]

Laserdisc (1969)

Laserdisc technology, using a transparent disc,[130] was invented by David Paul Gregg in 1958 (and patented in 1961 and 1990).[131] By 1969, Philips developed a videodisc in reflective mode, which has great advantages over the transparent mode. MCA and Philips decided to join forces. They first publicly demonstrated the videodisc in 1972. Laserdisc entered the market in Atlanta, on 15 December 1978, two years after the VHS VCR and four years before the CD, which is based on Laserdisc technology. Philips produced the players and MCA made the discs.

Compact disc (1979)

The compact disc was jointly developed by Philips (Joop Sinjou) and Sony (Toshitada Doi). In the early 1970s, Philips' researchers started experiments with "audio-only" optical discs, and at the end of the 1970s, Philips, Sony, and other companies presented prototypes of digital audio discs.

Bluetooth (1990s)

Bluetooth, a low-energy, peer-to-peer wireless technology was originally developed by Dutch electrical engineer Jaap Haartsen and Swedish engineer Sven Mattisson in the 1990s, working at Ericsson in Lund, Sweden. It became a global standard of short distance wireless connection.

Wi-fi (1990s)

In 1991, NCR Corporation/AT&T Corporation invented the precursor to 802.11 in Nieuwegein. Dutch electrical engineer Vic Hayes chaired IEEE 802.11 committee for 10 years, which was set up in 1990 to establish a wireless networking standard. He has been called the father of Wi-Fi (the brand name for products using IEEE 802.11 standards) for his work on IEEE 802.11 (802.11a & 802.11b) standard in 1997.

DVD (1995)

The DVD optical disc storage format was invented and developed by Philips and Sony in 1995.

Ambilight (2002)

Ambilight, short for "ambient lighting", is a lighting system for televisions developed by Philips in 2002.

Blu-ray (2006)

Philips and Sony in 1997 and 2006 respectively, launched the Blu-ray video recording/playback standard.

Computer science and information technology

Dijkstra's algorithm (1956)

Dijkstra's algorithm, conceived by Dutch computer scientist Edsger Dijkstra in 1956 and published in 1959, is a graph search algorithm that solves the single-source shortest path problem for a graph with non-negative edge path costs, producing a shortest path tree. This algorithm is often used in routing and as a part of other graph algorithms.

Shunting-yard algorithm (1960)

In computer science, the shunting-yard algorithm is a method for parsing mathematical expressions specified in infix notation. It can be used to produce output in Reverse Polish notation (RPN) or as an abstract syntax tree (AST). The algorithm was invented by Edsger Dijkstra and named the "shunting yard" algorithm because its operation resembles that of a railroad shunting yard. Dijkstra first described the Shunting Yard Algorithm in the Mathematisch Centrum report.

Schoonschip (early computer algebra system) (1963)

In 1963/64, during an extended stay at SLAC, Dutch theoretical physicist Martinus Veltman designed the computer program Schoonschip for symbolic manipulation of mathematical equations, which is now considered the very first computer algebra system.

Mutual exclusion (1965)

In computer science, mutual exclusion refers to the requirement of ensuring that no two concurrent processes are in their critical section at the same time; it is a basic requirement in concurrency control, to prevent race conditions. The requirement of mutual exclusion was first identified and solved by Edsger W. Dijkstra in his seminal 1965 paper titled Solution of a problem in concurrent programming control,[132][133] and is credited as the first topic in the study of concurrent algorithms.[134]

Semaphore (programming) (1965)

The semaphore concept was invented by Dijkstra in 1965 and the concept has found widespread use in a variety of operating systems.

Sleeping barber problem (1965)

In computer science, the sleeping barber problem is a classic inter-process communication and synchronization problem between multiple operating system processes. The problem is analogous to that of keeping a barber working when there are customers, resting when there are none and doing so in an orderly manner. The Sleeping Barber Problem was introduced by Edsger Dijkstra in 1965.[135]

Banker's algorithm (deadlock prevention algorithm) (1965)

The Banker's algorithm is a resource allocation and deadlock avoidance algorithm developed by Edsger Dijkstra that tests for safety by simulating the allocation of predetermined maximum possible amounts of all resources, and then makes an "s-state" check to test for possible deadlock conditions for all other pending activities, before deciding whether allocation should be allowed to continue. The algorithm was developed in the design process for the THE operating system and originally described (in Dutch) in EWD108.[136] The name is by analogy with the way that bankers account for liquidity constraints.

Dining philosophers problem (1965)

In computer science, the dining philosophers problem is an example problem often used in concurrent algorithm design to illustrate synchronization issues and techniques for resolving them. It was originally formulated in 1965 by Edsger Dijkstra as a student exam exercise, presented in terms of computers competing for access to tape drive peripherals. Soon after, Tony Hoare gave the problem its present formulation.[137][138][139]

Dekker's algorithm (1965)

Dekker's algorithm is the first known correct solution to the mutual exclusion problem in concurrent programming. Dijkstra attributed the solution to Dutch mathematician Theodorus Dekker in his manuscript on cooperating sequential processes. It allows two threads to share a single-use resource without conflict, using only shared memory for communication. Dekker's algorithm is the first published software-only, two-process mutual exclusion algorithm.

Van Wijngaarden grammar (1968)

Van Wijngaarden grammar (also vW-grammar or W-grammar) is a two-level grammar that provides a technique to define potentially infinite context-free grammars in a finite number of rules. The formalism was invented by Adriaan van Wijngaarden to rigorously define some syntactic restrictions that previously had to be formulated in natural language, despite their formal content. Typical applications are the treatment of gender and number in natural language syntax and the well-definedness of identifiers in programming languages. The technique was used and developed in the definition of the programming language ALGOL 68. It is an example of the larger class of affix grammars.

Structured programming (1968)

In 1968, computer programming was in a state of crisis. Dijkstra was one of a small group of academics and industrial programmers who advocated a new programming style to improve the quality of programs. Dijkstra coined the phrase "structured programming" and during the 1970s this became the new programming orthodoxy.

EPROM (1971)

An EPROM or erasable programmable read only memory, is a type of memory chip that retains its data when its power supply is switched off. Development of the EPROM memory cell started with investigation of faulty integrated circuits where the gate connections of transistors had broken. Stored charge on these isolated gates changed their properties. The EPROM was invented by the Amsterdam-born Israeli electrical engineer Dov Frohman in 1971, who was awarded US patent 3660819[140] in 1972.

Self-stabilization (1974)

Self-stabilization is a concept of fault-tolerance in distributed computing. A distributed system that is self-stabilizing will end up in a correct state no matter what state it is initialized with. That correct state is reached after a finite number of execution steps. Many years after the seminal paper of Edsger Dijkstra in 1974, this concept remains important as it presents an important foundation for self-managing computer systems and fault-tolerant systems. As a result, Dijkstra's paper received the 2002 ACM PODC Influential-Paper Award, one of the highest recognitions in the distributed computing community.[141]

Dijkstra-Scholten algorithm (1980)

The Dijkstra–Scholten algorithm (named after Edsger W. Dijkstra and Carel S. Scholten) is an algorithm for detecting termination in a distributed system.[142][143] The algorithm was proposed by Dijkstra and Scholten in 1980.[144]

Smoothsort (1981)

Smoothsort[145] is a comparison-based sorting algorithm. It is a variation of heapsort developed by Edsger Dijkstra in 1981. Like heapsort, smoothsort's upper bound is O(n log n). The advantage of smoothsort is that it comes closer to O(n) time if the input is already sorted to some degree, whereas heapsort averages O(n log n) regardless of the initial sorted state.

Amsterdam Compiler Kit (1983)

The Amsterdam Compiler Kit (ACK) is a fast, lightweight and retargetable compiler suite and toolchain developed by Andrew Tanenbaum and Ceriel Jacobs at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. It is MINIX's native toolchain. The ACK was originally closed-source software (that allowed binaries to be distributed for MINIX as a special case), but in April 2003 it was released under an open source BSD license. It has frontends for programming languages C, Pascal, Modula-2, Occam, and BASIC. The ACK's notability stems from the fact that in the early 1980s it was one of the first portable compilation systems designed to support multiple source languages and target platforms.[146][147]

Eight-to-fourteen modulation (1985)

EFM (Eight-to-Fourteen Modulation) was invented by Dutch electrical engineer Kees A. Schouhamer Immink in 1985. EFM is a data encoding technique – formally, a channel code – used by CDs, laserdiscs and pre-Hi-MD MiniDiscs.

MINIX (1987)

MINIX (from "mini-Unix") is a Unix-like computer operating system based on a microkernel architecture. Early versions of MINIX were created by Andrew S. Tanenbaum for educational purposes. Starting with MINIX 3, the primary aim of development shifted from education to the creation of a highly reliable and self-healing microkernel OS. MINIX is now developed as open-source software. MINIX was first released in 1987, with its complete source code made available to universities for study in courses and research. It has been free and open source software since it was re-licensed under the BSD license in April 2000. Tanenbaum created MINIX at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam to exemplify the principles conveyed in his textbook, Operating Systems: Design and Implementation (1987).

Amoeba (operating system) (1989)

Amoeba is a distributed operating system developed by Andrew S. Tanenbaum and others at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. The aim of the Amoeba project was to build a timesharing system that makes an entire network of computers appear to the user as a single machine. The Python programming language was originally developed for this platform.[148]

Python (programming language) (1989)

Python is a widely used general-purpose, high-level programming language. Its design philosophy emphasizes code readability, and its syntax allows programmers to express concepts in fewer lines of code than would be possible in languages such as C. The language provides constructs intended to enable clear programs on both a small and large scale.

Python was conceived in the late 1980s and its implementation was started in December 1989 by Guido van Rossum at CWI in the Netherlands as a successor to the ABC language (itself inspired by SETL) capable of exception handling and interfacing with the Amoeba operating system. Van Rossum is Python's principal author, and his continuing central role in deciding the direction of Python is reflected in the title given to him by the Python community, benevolent dictator for life (BDFL).

Since 2008, Python has consistently ranked in the top eight most popular programming languages as measured by the TIOBE Programming Community Index. It is the third most popular language whose grammatical syntax is not predominantly based on C, e.g. C++, C#, Objective-C, Java. Python does borrow heavily, however, from the expression and statement syntax of C, making it easier for programmers to transition between languages.

An empirical study found that, for a programming problem involving string manipulation and search in a dictionary, scripting languages such as Python were more productive than conventional languages such as C and Java. Memory consumption was often "better than Java and not much worse than C or C++". Large organizations that make use of Python include Google, Yahoo!, CERN, NASA, and some smaller ones like ILM, and ITA.

Vim (text editor) (1991)

Vim is a text editor written by the Dutch free software programmer Bram Moolenaar and first released publicly in 1991. Based on the Vi editor common to Unix-like systems, Vim carefully separated the user interface from editing functions. This allowed it to be used both from a command line interface and as a standalone application in a graphical user interface.

Blender (1995)

Blender is a free and open-source 3D computer graphics software product used for creating animated films, visual effects, art, 3D printed models, interactive 3D applications and video games. Blender's features include 3D modeling, UV unwrapping, texturing, raster graphics editing, rigging and skinning, fluid and smoke simulation, particle simulation, soft body simulation, sculpting, animating, match moving, camera tracking, rendering, video editing and compositing. Alongside the modelling features it also has an integrated game engine.

The Dutch animation studio Neo Geo and Not a Number Technologies (NaN) developed Blender as an in-house application, with the primary author being Ton Roosendaal. The name Blender was inspired by a song by Yello, from the album Baby.[149] Roosendaal founded NaN in June 1998 to further develop and distribute the program. They initially distributed the program as shareware until NaN went bankrupt in 2002.

The creditors agreed to release Blender under the GNU General Public License, for a one-time payment of €100,000 (US$100,670 at the time). On July 18, 2002, Roosendaal started a Blender funding campaign to collect donations, and on September 7, 2002, announced that they had collected enough funds and would release the Blender source code. Today, Blender is free, open-source software and is—apart from the Blender Institute's two half-time and two full-time employees—developed by the community.[150]

The Blender Foundation initially reserved the right to use dual licensing, so that, in addition to GNU GPL, Blender would have been available also under the Blender License that did not require disclosing source code but required payments to the Blender Foundation. However, they never exercised this option and suspended it indefinitely in 2005.[151] Currently, Blender is solely available under GNU GPL.

EFMPlus (1995)

EFMPlus is the channel code used in DVDs and SACDs, a more efficient successor to EFM used in CDs. It was created by Dutch electrical engineer Kees A. Schouhamer Immink, who also designed EFM. It is 6% less efficient than Toshiba's SD code, which resulted in a capacity of 4.7 gigabytes instead of SD's original 5 GB. The advantage of EFMPlus is its superior resilience against disc damage such as scratches and fingerprints.

Economics

Institutional foundations of modern corporation (first multinational, joint-stock, public limited company) (1602)

The Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC), founded in 1602, was the world’s first multinational, joint-stock,[152] limited liability corporation[153][154][155][156][157][158][159][160] - as well as its first government-backed trading cartel.[161][162][163][164] It was the first company to issue shares of stock and what evolved into corporate bonds. The VOC was also the first company to actually issue stocks and bonds through a stock exchange.[165][166][167][168] In 1602, the VOC issued shares that were made tradable on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange. This invention enhanced the ability of joint-stock companies to attract capital from investors as they could now easily dispose their shares. The company was known throughout the world as the VOC thanks to its logo featuring those initials, which became the first global corporate brand. The company's monogram also became the first global logo.[169]

The seventeenth-century Dutch merchants laid the foundations for the birth and development of modern corporations that now operate in many countries around the world.[170][171] The Dutch merchants were also the pioneers in laying the basis for modern corporate governance.[172] It was the VOC that invented the idea in 1606 of investing in the company rather than in a specific venture governed by the company.[173] The VOC is generally viewed as the first modern corporation.[174][175] With its legal personhood, permanent capital with transferable shares, separation of ownership and management, and limited liability for both shareholders and managers (or The Heeren XVII, who served as the board of directors of the company), the Dutch East India Company (VOC) is generally considered a major institutional breakthrough.[176] Motivated by international trade and the risks of venture capital, the VOC pioneered two of the most important riskmanagement innovations known, the implicit limited liability of shareholders and a secondary market for equity shares on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.[155][177][178][179][180][181][182][183] The VOC marked a commercial breakthrough. It conducted semipermanent business ventures, instead of contracting with different shareholders for each undertaking. Other firms soon followed suit.[184] The VOC's success inspired imitation across Europe—from Russia to Portugal.[171] Unlike the competing British East India Company founded in 1600, the VOC allowed anyone to purchase stock in the trading at the open-air Amsterdam Bourse.[185][186] Within a few decades, the VOC proved itself to be the most powerful trading corporation in the seventeenth-century world and the model for the large-scale business enterprises that now dominate the global economy.[187][188] As Timothy Brook commented: "The Dutch East India Company—the VOC, as it is known—is to corporate capitalism what Benjamin Franklin's kite is to electronics: the beginning of something momentous that could not have been predicted at the time."[189] The VOC's institutional innovations made large-scale trade feasible for the first time in history. These innovations allowed a single company to mobilize financial resources from a large number of investors and create ventures at a scale that had previously only been possible for monarchs.[190] The key to the success of the VOC was that its ownership had been opened up to the general public. The VOC, for the very first time in history, enabled investors from all strata of the population to invest in a company that intended to continue to exist for many years. This enabled the vast sum of 6.5 million guilders to be raised. During its golden age, the VOC was the pioneering model for the modern corporations in corporate governance, entrepreneurship, performance, and profitability.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was the first permanently organized joint-stock company, with a permanent capital base (fixed capital stock).[191][192][193][194][195][196][197] In 1602, the world's first official stock exchange (Amsterdam Stock Exchange or Amsterdam Bourse) was established by the VOC for dealings in its printed stocks and bonds. In the same year, The VOC undertook the world's first recorded IPO and, therefore, became the first public company to issue stock. It also played an integral role in modern history's first market crash. In 2010, a history student from Utrecht University, found the world’s oldest known ‘share’ during his thesis research in the Westfries Archief in Hoorn. It dates from 1606 and was issued by the VOC chamber of Enkhuizen.

The VOC is generally considered to be the world's first truly multinational corporation since it was the first transnational enterprise to issue stock. Some historians such as Timothy Brook and Russell Shorto consider the VOC as the first pioneering corporation in the first wave of globalization.[198][199] The VOC was the first multinational corporation to operate officially in different continents such as Europe, Asia and Africa. While the VOC mainly operated in what later became the Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia), the company also had important operations elsewhere. It employed people from different continents and origins in the same functions and working environments. Although it was a Dutch company its employees included not only people from the Netherlands, but also many from Germany and from other countries as well. Besides the diverse north-west European workforce recruited by the VOC in the Dutch Republic, the VOC made extensive use of local Asian labour markets. As a result, the personnel of the various VOC offices in Asia consisted of European and Asian employees. Asian or Eurasian workers might be employed as sailors, soldiers, writers, carpenters, smiths, or as simple unskilled workers.[200] At the height of its existence the VOC had 25,000 employees worked in Asia and 11,000 were en route.[201] Also, while most of its shareholders were Dutch, about a quarter of the initial shareholders were Zuid-Nederlanders (people from an area that includes modern Belgium and Luxembourg) and there were also a few dozen Germans.[202]

.jpg)

The VOC is usually considered the world's first publicly traded company.[160][204][205] The company was the first institutionalized trading company to have many of the attributes of the present public limited company.[154][206] In the first decades of the 17th century, the VOC was also the first recorded company ever to pay regular dividends, which averaged an annual 18% for almost 200 years (1602-1799).

The VOC was the first wholly recognized limited liability company.[155][207][208][209][210][211][212] The VOC had two types of shareholders: the participanten, who could be seen as non-managing members, and the 76 bewindhebbers (later reduced to 60) who acted as managing directors. This was the usual set-up for Dutch joint-stock companies at the time. The innovation in the case of the VOC was, that the liability of not just the participanten, but also of the bewindhebbers was limited to the paid-in capital (usually, bewindhebbers had unlimited liability). The VOC therefore was a limited liability company. Also, the capital would be permanent during the lifetime of the company. As a consequence, investors that wished to liquidate their interest in the interim could only do this by selling their share to others on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.[213] Confusion of confusions, a 1688 dialogue by the Sephardi Jew Joseph de la Vega analyzed the workings of this one-stock exchange.

In terms of creating a corporate identity for example, the VOC had its own logo, which it placed on all kinds of objects—official documents bore the VOC monogram seal, its packaged crates of goods were branded with the same, its property—cannons to pewter to porcelain, all were variously monogrammed.[214] The VOC's monogram became the best-known company trademark of the early modern period, possibly in fact the first globally recognized corporate logo.[187]

First megacorporation (1602)

The Dutch East India Company was arguably the first megacorporation, possessing quasi-governmental powers, including the ability to wage war, imprison and execute convicts, negotiate treaties, coin money and establish colonies. Many economic and political historians consider the Dutch East India Company as the most valuable, powerful and influential corporation in the world history.

The VOC existed for almost 200 years from its founding in 1602, when the States-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly over Dutch operations in Asia until its demise in 1796. During those two centuries (between 1602 and 1796), the VOC sent almost a million Europeans to work in the Asia trade on 4,785 ships, and netted for their efforts more than 2.5 million tons of Asian trade goods. By contrast, the rest of Europe combined sent only 882,412 people from 1500 to 1795, and the fleet of the English (later British) East India Company, the VOC's nearest competitor, was a distant second to its total traffic with 2,690 ships and a mere one-fifth the tonnage of goods carried by the VOC. The VOC enjoyed huge profits from its spice monopoly through most of the 17th century.[215]

Considered to be the largest corporation in history,[163] the VOC was even larger than some countries. By 1669, the VOC was the richest private company the world had ever seen, with over 150 merchant ships, 40 warships, 50,000 employees, a private army of 10,000 soldiers, and a dividend payment of 40% on the original investment.[216][217][218][219]

The VOC had considerable influences on the history of some countries and territories such as New Netherland, Indonesia, Australia, South Africa, Taiwan and Japan. The VOC trade post on Dejima, an artificial island off the coast of Nagasaki, was for more than two hundred years the only place where Europeans were permitted to trade with Japan. Rangaku (literally "Dutch Learning", and by extension "Western Learning") is a body of knowledge developed by Japan through its contacts with the Dutch enclave of Dejima, which allowed Japan to keep abreast of Western technology and medicine in the period when the country was closed to foreigners, 1641–1853, because of the Tokugawa shogunate’s policy of national isolation (sakoku).[220][221]

In terms of world history of geography and exploration, the VOC can be credited with putting most of Australia's coast (then Nova Hollandia and other names) on the world map, between 1606 and 1756.[222] The VOC's exploratory voyages such as those led by Willem Janszoon (Duyfken), Henry Hudson (Halve Maen) and Abel Tasman revealed vast new territories to Europeans.

Dutch auction (1600s)

A Dutch auction is also known as an open descending price auction. Named after the famous auctions of Dutch tulip bulbs in the 17th century, it is based on a pricing system devised by Nobel Prize–winning economist William Vickrey. In the traditional Dutch auction, the auctioneer begins with a high asking price which is lowered until some participant is willing to accept the auctioneer's price. The winning participant pays the last announced price. Dutch auction is also sometimes used to describe online auctions where several identical goods are sold simultaneously to an equal number of high bidders. In addition to cut flower sales in the Netherlands, Dutch auctions have also been used for perishable commodities such as fish and tobacco.

First modern art market (1600s)

The Dutch Republic was the birthplace of the first modern art market (open art market or free art market). The seventeenth-century Dutch were the pioneering arts marketers, successfully combining art and commerce together as we would recognise it today.[223] Until the 17th century, commissioning works of art was largely the preserve of the church, monarchs and aristocrats. The emergence of a powerful and wealthy middle class in Holland, though, produced a radical change in patronage as the new Dutch bourgeoisie bought art. For the first time, the direction of art was shaped by relatively broadly-based demand rather than religious dogma or royal whim, and the result was a market which today's dealers and collectors would find familiar. With the creation of the first large-scale open art market, prosperous Dutch merchants, artisans, and civil servants bought paintings and prints in unprecedented numbers. Foreign visitors were astonished that even modest members of Dutch society such as farmers and bakers owned multiple works of art. Dutch 17th-century art saw the rise of new subjects, as landscapes, still lifes, and scenes of daily life replaced formerly dominant religious images and scenes from classical mythology.[224]

Concept of corporate governance (1600s)

The seventeenth-century Dutch businessmen were the pioneers in laying the basis for modern corporate governance. Isaac Le Maire, an Amsterdam businessman and a sizeable shareholder of the VOC, became the first recorded investor to actually consider the corporate governance's problems. In 1609, he complained of the VOC's shoddy corporate governance. On January 24, 1609, Le Maire filed a petition against the VOC, marking the first recorded expression of shareholder activism. In what is the first recorded corporate governance dispute, Le Maire formally charged that the directors (the VOC's board of directors – the Heeren XVII) sought to “retain another’s money for longer or use it ways other than the latter wishes” and petitioned for the liquidation of the VOC in accordance with standard business practice.[225][226][227] Initially the largest single shareholder in the VOC and a bewindhebber sitting on the board of governors, Le Maire apparently attempted to divert the firm’s profits to himself by undertaking 14 expeditions under his own accounts instead of those of the company. Since his large shareholdings were not accompanied by greater voting power, Le Maire was soon ousted by other governors in 1605 on charges of embezzlement, and was forced to sign an agreement not to compete with the VOC. Having retained stock in the company following this incident, in 1609 Le Maire would become the author of what is celebrated as “the first recorded expression of investor advocacy” in history.[228][229][230]

The first shareholder revolt happened in 1622, among Dutch East India Company (VOC) investors who complained that the company account books had been “smeared with bacon” so that they might be “eaten by dogs.” The investors demanded a “reeckeninge,” a proper financial audit.[231] The 1622 campaign by the shareholders of the VOC is a testimony of genesis of CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) in which shareholders staged protests by distributing pamphlets and complaining about management self enrichment and secrecy.[232]

Modern concept of foreign direct investment (1600s)

The construction in 1619 of a train-oil factory on Smeerenburg in the Spitsbergen islands by the Noordsche Compagnie, and the acquisition in 1626 of Manhattan Island by the Dutch West India Company are referred to as the earliest cases of outward foreign direct investment (FDI) in Dutch and world history. Throughout the seventeenth century, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Dutch West India Company (GWIC/WIC) also began to create trading settlements around the globe. Their trading activities generated enormous wealth, making the Dutch Republic one of the most prosperous countries of that time. The Dutch Republic's extensive arms trade occasioned an episode in the industrial development of early-modern Sweden, where arms merchants like Louis de Geer and the Trip brothers, invested in iron mines and iron works, another early example of outward foreign direct investment.

First modern market-oriented economy (1600s)

It was in the Dutch Republic that some important industries (economic sectors) such as shipbuilding, shipping, printing and publishing were developed on a large-scale export-driven model for the first time in history. The ship building district of Zaan, near Amsterdam, became the first industrialized area in the world,[233] with around 900 industrial windmills at the end of the 17th century, but there were industrialized towns and cities on a smaller scale also. Other industries that saw significant growth were papermaking, sugar refining, printing, the linen industry (with spin-offs in vegetable oils, like flax and rape oil), and industries that used the cheap peat fuel, like brewing and ceramics (brickworks, pottery and clay-pipe making).

The Dutch shipbuilding industry was of modern dimensions, inclining strongly toward standardised, repetitive methods. It was highly mechanized and used many labor-saving devices-wind-powered sawmills, powered feeders for saw, block and tackles, great cranes to move heavy timbers-all of which increased productivity.[234] Dutch shipbuilding benefited from various design innovations which increased carrying capacity and cut costs.[79][235][236][237][238][239] Dutch warships were the best in the world and their merchant fleet was equally outstanding. The size of the Dutch merchant fleet in the 1670s probably exceeded the combined fleets of England, France, Spain, Portugal, and Germany. The Dutch Republic dominated herring fishing in the North Sea, cod fishing off Iceland and whaling at Spitzbergen in the Arctic.[7] By the last quarter of the seventeenth century, Dutch shipping dominated the world's carrying trade, growing tenfold between 1500 and 1700 (Wallerstein 1980:46)[240] “By seventeenth century standards,” Richard Unger affirms, Dutch shipbuilding “was a massive industry and larger than any shipbuilding industry which had preceded it.”[241] During his undercover visit to the Dutch Republic as part of the Grand Embassy mission (1697-1698), Peter the Great wanted to learn more about the Dutch shipbuilding industry. He studied shipbuilding and carpentry in Zaandam and Amsterdam. Through the agency of Nicolaas Witsen, cartographer, mayor of Amsterdam and expert on Russia, he worked at the Dutch East India Company (VOC) shipyard. In order to modernise the Imperial Russia, Peter introduced these Dutch crafts and skills in his home country and in particular in the newly founded capital of his Russian empire Saint Petersburg.[242][243][244]

In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the Dutch-speaking peoples came to dominate not only the print trade (having replaced the Italians), but also the map making and map printing industry by virtue of their own travels, trade ventures, and widespread commercial networks. The Dutch initiated what we would call today the free flow of geographical information. The Ducth publishing centers of Antwerp and Amsterdam would eclipse the former centers of cartographic activity. During the seventeenth century, the Dutch publishing industry was arguably the largest and most sophisticated in Europe. The Netherlands had developed into the 'publishing house of Europe', thanks to an extensive trade in printed matter that chiefly comprised the mass reprinting of foreign publications. The privilege system played an essential role in this large-scale publication of printed matter. While the system had long been maintained in France as a tool for censorship, in the Netherlands it tended to be exploited by the publishers as an effective instrument for monopolising the market. The Dutch publishing industry flourished in the liberal political climate, where progressive ideas could appear in print without a problem.[245][246][247] By the middle of the seventeenth century the United Provinces had become the undisputed centre of the European book trade, producing a larger assortment of books and other printed material than anywhere else in Europe. Dutch publishing was successful internationally in two ways. Firstly, the Dutch monopolised the trade in publications. Secondly, the Dutch printed a large part of the total European book production. Many exiles and freethinkers chose to move to the United Provinces. The Dutch Republic became a mass producer of illegal pamphlets and forbidden books.[248][249]

First capitalist nation-state (foundations of modern capitalism) (1600s)

Economic historians consider the Netherlands as the first predominantly capitalist nation.[33][183][251][252][253][254][255][256][257][258][259] The development of European capitalism began among the city-states of Italy, Flanders, and the Baltic. It spread to the European interstate system, eventually resulting in the world's first capitalist nation-state, the Dutch Republic of the seventeenth century.[260] The Dutch were the first to develop capitalism on a nationwide scale (as opposed to earlier city states). They also played a pioneering role in the emergence of the capitalist world-system.[261] Simon Schama aptly titled his work The Embarrassment of Riches, capturing the astonishing novelty and success of the commercial revolution in the Dutch Republic. The Dutch, it seems, more than anyone in the West since the palmy days of ancient Rome, had more money than they knew what to do with. They discovered, unlike the Romans, that the best use of money was to make more money. They invested it, mostly in overseas ventures, utilizing the innovation of the joint-stock company in which private investors could purchase shares, the most famous being the Dutch East India Company.[262] Wherever Dutch capital went, there urban features were developed, economic activities expanded, new industries established, new jobs created, trading companies operated, swamps drained, mines opened, forests exploited, canals constructed, mills turned, and ships were built. The Dutch were pioneering venture capitalists who raised the commercial and industrial potential of underdeveloped lands whose resources they exploited. This paved the way to the Dutch Republic's prosperity, as it can pave the way to prosperity elsewhere.[263][264][265] The United Provinces of the Netherlands were the land in which the capitalist spirit for the first time attained its fullest maturity.[266][267][268] Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) includes dozens of references to the Dutch Republic's capitalist economic model.[269] Karl Marx described the Dutch Republic or Holland as “the model capitalist nation of the seventeenth century”, which was in “the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production”. He concluded that “the total capital of the Republic was probably more important than that of all the rest of Europe put together”.[270][271][272][273][274][275] As John Steele Gordon (1999) commented “The Dutch invented modern capitalism in the early seventeenth century. Although many of the basic concepts had first appeared in Italy during the Renaissance, the Dutch, especially the citizens of the city of Amsterdam, were the real innovators. They transformed banking, stock exchanges, credit, insurance, and limited-liability corporations into a coherent financial and commercial system.” They brought these techniques/institutions together and established them on a secure basis in a merchant economy organized around a common for-profit motive.[276] In Early modern Europe it featured the wealthiest trading city (Amsterdam) and the first full-time stock exchange. The traders created insurance and retirement funds, along with less benign phenomena, such as the boom-bust cycle, the world's first asset-inflation bubble, the Tulip mania of 1636–1637. But the bursting of the tulip bubble did not end Dutch economic hegemony. Tulipmania was followed by a century of Dutch leadership in almost every branch of global commerce, finance, and manufacturing. It was in the Netherlands that the early techniques of stock-market manipulation were developed, such as short selling (selling stock one doesn't own, in hopes of a fall in price), bear raids (where insiders conspire to sell a stock short until the outsiders panic and sell out their holdings, allowing the insiders to close their shorts profitably), syndicates (where a group manipulates a stock price by buying and selling among themselves), and corners (where a person or syndicate secretly acquires the entire floating supply of a commodity, forcing all who need to buy the commodity to do so at their price).[277] The seventeenth-century Dutch merchants were pioneering venture capitalists at the dawn of modern capitalism.[278][279][280] Motivated by international trade and the risks of venture capital, the Dutch United East India Company pioneered two of the most important riskmanagement innovations known, the implicit limited liability of shareholders and a secondary market for equity shares on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.[182] As Timothy Brook commented “the Dutch East India Company—the VOC, as it is known—is to corporate capitalism what Benjamin Franklin's kite is to electronics: the beginning of something momentous that could not have been predicted at the time.”[281] World-systems theorists (including Immanuel Wallerstein and Giovanni Arrighi) often consider the economic primacy of the Dutch Republic in the 17th century as the first capitalist hegemony[282][283][284][285][286][287][288][289] in world history (followed by hegemonies of the United Kingdom in the 19th century and the United States in the 20th century).

First modern economic miracle (1585–1714)