Liouville's theorem (differential algebra)

In mathematics, Liouville's theorem, originally formulated by Joseph Liouville in the 1830s and 1840s, places an important restriction on antiderivatives that can be expressed as elementary functions.

The antiderivatives of certain elementary functions cannot themselves be expressed as elementary functions. A standard example of such a function is  whose antiderivative is (with a multiplier of a constant) the error function, familiar from statistics. Other examples include the functions

whose antiderivative is (with a multiplier of a constant) the error function, familiar from statistics. Other examples include the functions  and

and  .

.

Liouville's theorem states that elementary antiderivatives, if they exist, must be in the same differential field as the function, plus possibly a finite number of logarithms.

Definitions

For any differential field F, there is a subfield

- Con(F) = {f in F | Df = 0},

called the constants of F. Given two differential fields F and G, G is called a logarithmic extension of F if G is a simple transcendental extension of F (i.e. G = F(t) for some transcendental t) such that

- Dt = Ds/s for some s in F.

This has the form of a logarithmic derivative. Intuitively, one may think of t as the logarithm of some element s of F, in which case, this condition is analogous to the ordinary chain rule. But it must be remembered that F is not necessarily equipped with a unique logarithm; one might adjoin many "logarithm-like" extensions to F. Similarly, an exponential extension is a simple transcendental extension that satisfies

- Dt = t Ds.

With the above caveat in mind, this element may be thought of as an exponential of an element s of F. Finally, G is called an elementary differential extension of F if there is a finite chain of subfields from F to G where each extension in the chain is either algebraic, logarithmic, or exponential.

Basic theorem

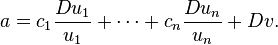

Suppose F and G are differential fields, with Con(F) = Con(G), and that G is an elementary differential extension of F. Let a be in F, y in G, and suppose Dy = a (in words, suppose that G contains an antiderivative of a). Then there exist c1, ..., cn in Con(F), u1, ..., un, v in F such that

In other words, the only functions that have "elementary antiderivatives" (i.e. antiderivatives living in, at worst, an elementary differential extension of F) are those with this form prescribed by the theorem. Thus, on an intuitive level, the theorem states that the only elementary antiderivatives are the "simple" functions plus a finite number of logarithms of "simple" functions.

A proof of Liouville's theorem can be found in section 12.4 of Geddes, et al.

Examples

As an example, the field C(x) of rational functions in a single variable has a derivation given by the standard derivative with respect to that variable. The constants of this field are just the complex numbers C.

The function  , which exists in C(x), does not have an antiderivative in C(x). Its antiderivatives ln x + C do, however, exist in the logarithmic extension C(x, ln x).

, which exists in C(x), does not have an antiderivative in C(x). Its antiderivatives ln x + C do, however, exist in the logarithmic extension C(x, ln x).

Likewise, the function  does not have an antiderivative in C(x). Its antiderivatives tan−1(x) + C do not seem to satisfy the requirements of the theorem, since they are not (apparently) sums of rational functions and logarithms of rational functions. However, a calculation with Euler's formula shows that in fact the antiderivatives can be written in the required manner (as logarithms of rational functions).

does not have an antiderivative in C(x). Its antiderivatives tan−1(x) + C do not seem to satisfy the requirements of the theorem, since they are not (apparently) sums of rational functions and logarithms of rational functions. However, a calculation with Euler's formula shows that in fact the antiderivatives can be written in the required manner (as logarithms of rational functions).

Relationship with differential Galois theory

Liouville's theorem is sometimes presented as a theorem in differential Galois theory, but this is not strictly true. The theorem can be proved without any use of Galois theory. Furthermore, the Galois group of a simple antiderivative is either trivial (if no field extension is required to express it), or is simply the additive group of the constants (corresponding to the constant of integration). Thus, an antiderivative's differential Galois group does not encode enough information to determine if it can be expressed using elementary functions, the major condition of Liouville's theorem.

References

- Bertrand, D. (1996), "Review of "Lectures on differential Galois theory"", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 33 (2), doi:10.1090/s0273-0979-96-00652-0, ISSN 0002-9904

- Geddes, Czapor, Labahn (1992). Algorithms for Computer Algebra. Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-9259-0.

- Magid, Andy R. (1994), Lectures on differential Galois theory, University Lecture Series 7, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-7004-4, MR 1301076

- Magid, Andy R. (1999), "Differential Galois theory", Notices of the American Mathematical Society 46 (9): 1041–1049, ISSN 0002-9920, MR 1710665

- van der Put, Marius; Singer, Michael F. (2003), Galois theory of linear differential equations, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften [Fundamental Principles of Mathematical Sciences] 328, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-44228-8, MR 1960772

![\begin{align}

e^{i \theta} & = \cos \theta + i \sin \theta \\

e^{-i \theta} & = \cos \theta - i \sin \theta \\

e^{2i \theta} & = \frac{e^{i \theta}}{e^{-i \theta}} = \frac{\cos \theta + i \sin \theta}{\cos \theta - i \sin \theta} \\

& = \frac{1 + i \tan \theta}{1 - i \tan \theta} \\[8pt]

2i \theta & = \ln \frac{1 + i \tan \theta}{1 - i \tan \theta} \\[8pt]

2i \tan^{-1} x & = \ln \frac{1 + ix}{1 - ix} \\[8pt]

\tan^{-1} x & = \frac{1}{2i} \ln \frac{1+ix}{1-ix}

\end{align}](../I/m/25fd0cb89242253a888c966ea68fa87e.png)