Linear combination of atomic orbitals

A linear combination of atomic orbitals or LCAO is a quantum superposition of atomic orbitals and a technique for calculating molecular orbitals in quantum chemistry.[1] In quantum mechanics, electron configurations of atoms are described as wavefunctions. In mathematical sense, these wave functions are the basis set of functions, the basis functions, which describe the electrons of a given atom. In chemical reactions, orbital wavefunctions are modified, i.e. the electron cloud shape is changed, according to the type of atoms participating in the chemical bond.

It was introduced in 1929 by Sir John Lennard-Jones with the description of bonding in the diatomic molecules of the first main row of the periodic table, but had been used earlier by Linus Pauling for H2+.[2][3]

A mathematical description follows.

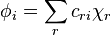

An initial assumption is that the number of molecular orbitals is equal to the number of atomic orbitals included in the linear expansion. In a sense, n atomic orbitals combine to form n molecular orbitals, which can be numbered i = 1 to n and which may not all be the same. The expression (linear expansion) for the i th molecular orbital would be:

or

where  (phi) is a molecular orbital represented as the sum of n atomic orbitals

(phi) is a molecular orbital represented as the sum of n atomic orbitals  (chi), each multiplied by a corresponding coefficient

(chi), each multiplied by a corresponding coefficient  , and r (numbered 1 to n) represents which atomic orbital is combined in the term. The coefficients are the weights of the contributions of the n atomic orbitals to the molecular orbital. The Hartree–Fock procedure is used to obtain the coefficients of the expansion.

, and r (numbered 1 to n) represents which atomic orbital is combined in the term. The coefficients are the weights of the contributions of the n atomic orbitals to the molecular orbital. The Hartree–Fock procedure is used to obtain the coefficients of the expansion.

The orbitals are thus expressed as linear combinations of basis functions, and the basis functions are one-electron functions centered on nuclei of the component atoms of the molecule. The atomic orbitals used are typically those of hydrogen-like atoms since these are known analytically i.e. Slater-type orbitals but other choices are possible like Gaussian functions from standard basis sets.

By minimizing the total energy of the system, an appropriate set of coefficients of the linear combinations is determined. This quantitative approach is now known as the Hartree–Fock method. However, since the development of computational chemistry, the LCAO method often refers not to an actual optimization of the wave function but to a qualitative discussion which is very useful for predicting and rationalizing results obtained via more modern methods. In this case, the shape of the molecular orbitals and their respective energies are deduced approximately from comparing the energies of the atomic orbitals of the individual atoms (or molecular fragments) and applying some recipes known as level repulsion and the like. The graphs that are plotted to make this discussion clearer are called correlation diagrams. The required atomic orbital energies can come from calculations or directly from experiment via Koopmans' theorem.

This is done by using the symmetry of the molecules and orbitals involved in bonding. The first step in this process is assigning a point group to the molecule. A common example is water, which is of C2v symmetry. Then a reducible representation of the bonding is determined demonstrated below for water:

Each operation in the point group is performed upon the molecule. The number of bonds that are unmoved is the character of that operation. This reducible representation is decomposed into the sum of irreducible representations. These irreducible representations correspond to the symmetry of the orbitals involved.

MO diagrams provide simple qualitative LCAO treatment.

Quantitative theories are the Hückel method, the extended Hückel method and the Pariser–Parr–Pople method.

See also

- Quantum chemistry computer programs

- Hartree–Fock method

- Basis set (chemistry)

- Tight binding

- Holstein–Herring method

External links

- LCAO @ chemistry.umeche.maine.edu Link

References

- ↑ Huheey, James. Inorganic Chemistry:Principles of Structure and Reactivity

- ↑ Friedrich Hund and Chemistry, Werner Kutzelnigg, on the occasion of Hund's 100th birthday, Angewandte Chemie, 35, 572–586, (1996), http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.199605721

- ↑ Robert S. Mulliken's Nobel Lecture, Science, 157, no. 3784, 13 - 24, (1967)