Limusaurus

| Limusaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic, 160Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Two fossil specimens exhibited in Tokyo (slab also contains a small crocodyliform) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Averostra |

| Clade: | †Ceratosauria |

| Genus: | †Limusaurus Xu et al., 2009 |

| Species: | † L. inextricabilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Limusaurus inextricabilis Xu et al., 2009 | |

Limusaurus (meaning "mud lizard") is a genus of toothless herbivorous theropod dinosaur from the Jurassic (Oxfordian stage) Upper Shishugou Formation in the Junggar Basin of western China.[1] Limusaurus is also the first definitely known ceratosaur from Eastern Asia, including China. The discovery of Limusaurus also suggests that there may have been a land connection between Asia and several other continents allowing for faunal exchange even though the Turgai Sea was previously thought to prohibit such a movement.[2]

The type species is L. inextricabilis. The specific name means "impossible to extricate".[2]

Description

The type, and to date the only species, L. inextricabilis, was described in a 2009 paper coauthored by X. Xu, J. M. Clark, J. Mo, J. Choiniere, C. A. Forster, G. M. Erickson, D. W. E. Hone, C. Sullivan, D. A. Eberth, S. Nesbitt, Q. Zhao, R. Hernandez, C.-K Jia, F.-L. Han, and Y. Guo in the journal Nature.[2] It is known from two subadult specimens found in close connection; the holotype, (IVPP) V 15923, is an almost complete articulated skeleton, and the other, IVPP V 15924, is a nearly completely articulated specimen, only missing the skull. The second specimen is 15% larger than the holotype. A third referred specimen is IVPP V16134. All specimens were young adults when they died, as can be concluded from the extent of bone fusion; from growth lines it was inferred that IVPP V 15924 was in its sixth year when it died.

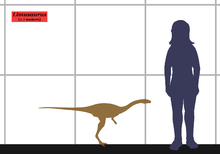

Limusaurus had a small slender body measuring about 1.7 m in length. It is the first definite ceratosaur from eastern Asia to be discovered and one of the earliest. Its discovery shows that the Asian dinosaurian fauna was less endemic during the Middle/Late Jurassic period than previously thought and suggests a possible land connection between Asia and other continents during that period.

Classification

Limusaurus is a basal ceratosaur that shares many characteristics with coelophysoids and tetanurans. The features present in Limusaurus led to the conclusion that there is a close relationship between the clades Ceratosauria and Tetanurae.

The following cladogram follows an analysis by Diego Pol and Oliver W. M. Rauhut, 2012.[3]

| Ceratosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Paleobiology

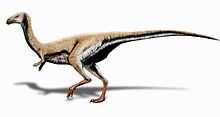

Limusaurus shares several cranial features with other ceratosaurs and coelophysids but displays some unique characteristics for the group, such as absence of teeth and the presence of a fully developed beak (rhamphotheca), which have been previously reported in non-avian theropods only among the Cretaceous coelurosaurs. Limusaurus has a long neck, short forelimbs and elongated hindlimbs indicating strong cursorial (running) capabilities. The presence of gastroliths in the stomach of both specimens and the toothless beak indicate a herbivorous diet, making it the earliest and most basal theropod to become adapted to eating plants. The overall aspect of the animal is very similar to that of the Cretaceous ornithomimid theropods, as well as the Triassic non-dinosaurian archosaur Effigia, representing a remarkable case of convergent evolution among these three distinct groups of archosaurs.[2]

Limusaurus was a very basal ceratosaur characterized by hands retaining four digits (I–IV), digit I being strongly reduced. It was traditionally thought that the hands of dinosaurs evolved into the wings of birds by the disappearance of the two outward digits (IV and V), in contradiction to embryological studies on birds that showed that the retained digits are the three middle ones (II–III–IV). The hand structure of Limusaurus with its reduced digit I adds more weight to the digit II–III–IV identities for Tetanurae, the group which includes birds. Previous to the discovery of Limusaurus, theropods were assumed to have progressively evolved reduced digits on the ulnar side of the manus. This concept, known as Lateral Digit Reduction (LDR) is in contrast to Bilateral Digit Reduction (BDR), the reduction on digits on both sides of the hand commonly seen in all other tetrapod groups excluding dinosaurs. However, in Limusaurus, the first digit (Digit I) is strongly reduced, along with other ceratosaurs, suggesting that BDR occurred in their sister group the Tetanurae as well.

Previously, it was thought that digits I–III were retained in tetanurans as a homology with basal theropods, giving credence to the LDR hypothesis. However, the evidence of BDR in Limusaurus suggests that other non-avian theropods may also have exhibited BDR and the apparent digits I–III in tetanurans may actually be digits II–IV, a previous idea considered by Thulborn and Hamley, but largely ignored in the paleontological community.[2][4]

Despite the interesting possibilities brought up by Limusaurus, paleontologists are unlikely to stop calling tetanuran digits I, II, and III and switch to calling them II, III, IV. This is because most of their morphological traits resemble those of digits I, II and III of other theropods. It remains possible that bilateral digit reduction occurred in Ceratosauria but not in Tetanurae. The embryology of the bird wing could be explained by a homeotic frameshift of digital identity, as suggested by recent gene expression and experimental data.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ New dinosaur gives bird wing clue. BBC News, June 17, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Xu, X., Clark, J.M., Mo, J., Choiniere, J., Forster, C.A., Erickson, G.M., Hone, D.W.E., Sullivan, C., Eberth, D.A., Nesbitt, S., Zhao, Q., Hernandez, R., Jia, C.-K., Han, F.-L., and Guo, Y. (2009). "A Jurassic ceratosaur from China helps clarify avian digital homologies." Nature, 459(18): 940–944. doi:10.1038/nature08124

- ↑ Diego Pol & Oliver W. M. Rauhut (2012). "A Middle Jurassic abelisaurid from Patagonia and the early diversification of theropod dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279 (1804): 3170–5. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0660. PMC 3385738. PMID 22628475.

- ↑ Thulborn, R.A. and Hamley, T.L. (1982). "The reptilian relationships of Archaeopteryx." Aust. J. Zool., 30: 611–634.

- ↑ Vargas AO, Wagner GP, and Gauthier JA. Limusaurus and bird digit identity. Available from Nature Precedings (2009)