Lifting-line theory

The Prandtl lifting-line theory,[1] also called the Lanchester–Prandtl wing theory[2] is a mathematical model for predicting the lift distribution over a three-dimensional wing based on its geometry.

The theory was expressed independently[3] by Frederick W. Lanchester in 1907,[4] and by Ludwig Prandtl in 1918–1919[5] after working with Albert Betz and Max Munk.

In this model, the vortex strength reduces along the wingspan, and the loss in vortex strength is shed as a vortex-sheet from the trailing edge, rather than just at the wing-tips.[6][7]

Introduction

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

It is observed that on a three-dimensional, finite wing, the lift over each wing segment (the local lift per unit span,  or

or  ) does not correspond merely to that predicted by two-dimensional analysis. Instead, this local amount of lift is strongly affected by the lift generated at the neighboring wing sections.

) does not correspond merely to that predicted by two-dimensional analysis. Instead, this local amount of lift is strongly affected by the lift generated at the neighboring wing sections.

As such, it is difficult to predict analytically the overall amount of lift that will be generated by a wing of given geometry. The lifting-line theory yields the lift distribution along the span-wise direction,  based only on the wing geometry (span-wise distribution of chord, airfoil, and twist) and flow conditions (

based only on the wing geometry (span-wise distribution of chord, airfoil, and twist) and flow conditions ( ,

,  ,

,  ).

).

Principle

The lifting-line theory makes use of the concept of circulation and of the Kutta–Joukowski theorem,

so that instead of the lift distribution function, the unknown effectively becomes the distribution of circulation over the span,  .

.

|

Modeling the (unknown and sought-after) local lift with the (also unknown) local circulation allows us to account for the influence of one section over its neighbors. In this view, any span-wise change in lift is equivalent to a span-wise change of circulation. According to the Helmholtz theorems, a vortex filament cannot begin or terminate in the air. As such, any span-wise change in lift can be modeled as the shedding of a vortex filament down the flow, behind the wing.

This shed vortex, whose strength is the derivative of the (unknown) local wing circulation distribution,  , influences the flow left and right of the wing section.

, influences the flow left and right of the wing section.

|

This sideways influence (upwash on the outboard, downwash on the inboard) is the key to the lifting-line theory. Now, if the change in lift distribution is known at given lift section, it is possible to predict how that section influences the lift over its neighbors: the vertical induced velocity (upwash or downwash,  ) can be quantified using the velocity distribution within a vortex, and related to a change in effective angle of attack over the neighboring sections.

) can be quantified using the velocity distribution within a vortex, and related to a change in effective angle of attack over the neighboring sections.

In mathematical terms, the local induced change of angle of attack  on a given section can be quantified with the integral sum of the downwash induced by every other wing section. In turn, the integral sum of the lift on each downwashed wing section is equal to the (known) total desired amount of lift.

on a given section can be quantified with the integral sum of the downwash induced by every other wing section. In turn, the integral sum of the lift on each downwashed wing section is equal to the (known) total desired amount of lift.

This leads to an integro-differential equation in the form of  where

where  is expressed solely in terms of the wing geometry and its own span-wise variation,

is expressed solely in terms of the wing geometry and its own span-wise variation,  . The solution to this equation is a function

. The solution to this equation is a function  which accurately describes the circulation (and therefore lift) distribution over a finite wing of known geometry.

which accurately describes the circulation (and therefore lift) distribution over a finite wing of known geometry.

Derivation[8]

Nomenclature:

is the circulation over the entire wing (m²/s)

is the circulation over the entire wing (m²/s) is the 3D lift coefficient (for the entire wing)

is the 3D lift coefficient (for the entire wing) is the aspect ratio

is the aspect ratio is the freestream angle of attack

is the freestream angle of attack is the freestream velocity

is the freestream velocity is the drag coefficient for induced drag

is the drag coefficient for induced drag is the planform efficiency factor

is the planform efficiency factor

The following are all functions of the wings span-wise station  (i.e. they can all vary along the wing)

(i.e. they can all vary along the wing)

is the 2D lift coefficient (units/m)

is the 2D lift coefficient (units/m) is the 2D circulation at a section (m/s)

is the 2D circulation at a section (m/s) is the chord length of the local section

is the chord length of the local section is the local change in angle of attack due to geometric twist of the wing

is the local change in angle of attack due to geometric twist of the wing is zero-lift angle of attack of that section (depends on the airfoil geometry)

is zero-lift angle of attack of that section (depends on the airfoil geometry) is the 2D lift coefficient slope (units/m⋅rad, and depends on airfoil geometry, see Thin airfoil theory)

is the 2D lift coefficient slope (units/m⋅rad, and depends on airfoil geometry, see Thin airfoil theory) is change in angle of attack due to downwash

is change in angle of attack due to downwash is the local downwash velocity

is the local downwash velocity

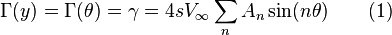

To derive the model we start with the assumption that the circulation of the wing varies as a function of the spanwise locations. The function assumed is a Fourier function. Firstly, the coordinate for the spanwise location  is transformed by

is transformed by  , where y is spanwise location, and s is the semi-span of the wing.

, where y is spanwise location, and s is the semi-span of the wing.

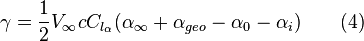

and so the circulation is assumed to be:

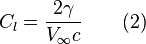

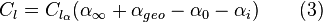

Since the circulation of a section is related the  by the equation:

by the equation:

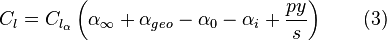

but since the coefficient of lift is a function of angle of attack:

hence the vortex strength at any particular spanwise station can be given by the equations:

This one equation has two unknowns: the value for  and the value for

and the value for  . However, the downwash is purely a function of the circulation only. So we can determine the value

. However, the downwash is purely a function of the circulation only. So we can determine the value  in terms of

in terms of  , bring this term across to the left hand side of the equation and solve. The downwash at any given station is a function of the entire shed vortex system. This is determined by integrating the influence of each differential shed vortex over the span of the wing.

, bring this term across to the left hand side of the equation and solve. The downwash at any given station is a function of the entire shed vortex system. This is determined by integrating the influence of each differential shed vortex over the span of the wing.

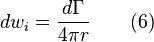

Differential element of circulation:

Differential downwash due to the differential element of circulation (acts like half an infinite vortex line):

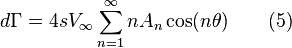

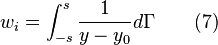

The integral equation over the span of the wing to determine the downwash at a particular location is:

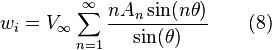

After appropriate substitutions and integrations we get:

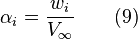

And so the change in angle attack is determined by (assuming small angles):

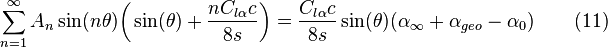

By substituting equations 8 and 9 into RHS of equation 4 and equation 1 into the LHS of equation 4, we then get:

![4 s V_\infty \sum_{n=1}^\infty A_n \sin(n \theta) = \frac{1}{2} V_\infty c C_{l_\alpha}\left[\alpha_\infty + \alpha_{geo} - \alpha_0 - \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{n A_n \sin(n \theta)}{\sin(\theta)} \right] \qquad (10)](../I/m/9d2680831f8afd628c6f40bf8b7037de.png)

After rearranging, we get the series of simultaneous equations:

By taking a finite number of terms, equation 11 can be expressed in matrix form and solved for coefficients A. Note the left-hand side of the equation represents each element in the matrix, and the terms on the RHS of equation 11 represent the RHS of the matrix form. Each row in the matrix form represents a different span-wise station, and each column represents a different value for n.

Appropriate choices for  are as a linear variation between

are as a linear variation between  . Note that this range does not include the values for

. Note that this range does not include the values for  , as this will lead to a singular matrix, which can't be solved.

, as this will lead to a singular matrix, which can't be solved.

Lift and drag from coefficients

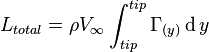

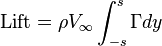

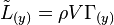

The lift can be determined by integrating the circulation terms:

which can be reduced to:

where  is the first term of the solution of the simultaneous equations shown above.

is the first term of the solution of the simultaneous equations shown above.

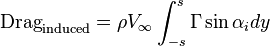

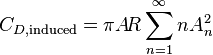

The induced drag can be determined from

or

Symmetric wing

For a symmetric wing, the even terms of the series coefficients are identically equal to 0, and so can be dropped.

Rolling wings

When the aircraft is rolling, and additional term may be added that will add the wing station distance multiplied by the rate of roll to give additional angle of attack change. Equation 3 will then become

where

is the rate of roll in rad/sec,

is the rate of roll in rad/sec,

Note that y can be negative. This addition will introduce non-zero even coefficients in the equation which will have to be accounted for.

Control deflection

The effect of ailerons can be accounted for simply changing  term in Equation 3. For non-symmetric controls such as ailerons the

term in Equation 3. For non-symmetric controls such as ailerons the  term will change on each side of the wing.

term will change on each side of the wing.

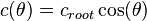

Elliptical wings

For an elliptical wing with no twist, the chord length is given as a function of span location as:

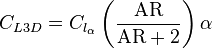

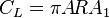

Useful approximations

A useful approximation is that

where

is the 3D lift coefficient for elliptical circulation distribution,

is the 3D lift coefficient for elliptical circulation distribution, is the 2D lift coefficient slope (see Thin Airfoil Theory),

is the 2D lift coefficient slope (see Thin Airfoil Theory), is the aspect ratio, and

is the aspect ratio, and is the angle of attack in radians.

is the angle of attack in radians.

The theoretical value for  is 2

is 2 . Note that this equation becomes the thin airfoil equation if AR goes to infinity.[9]

. Note that this equation becomes the thin airfoil equation if AR goes to infinity.[9]

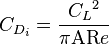

Lifting-line theory also states an equation for induced drag:.[10][11]

where

is the drag coefficient for induced drag,

is the drag coefficient for induced drag, is the lift coefficient, and

is the lift coefficient, and is the aspect ratio.

is the aspect ratio. is the planform efficiency factor (equals 1 for elliptical circulation distribution).

is the planform efficiency factor (equals 1 for elliptical circulation distribution).

Limitations of the theory

The lifting line theory does not take into account the following:

- Compressible flow

- Viscous flow

- Swept wings

- Low aspect ratio wings

- Unsteady flows

See also

- Horseshoe vortex

- Thin Airfoil Theory

- Vortex lattice method

Notes

- ↑ Anderson, John D. (2001), Fundamental of aerodynamics, McGraw-Hill, Boston. ISBN 0-07-237335-0. p360

- ↑ Houghton, E. L.; Carpenter, P.W. (2003). Butterworth Heinmann, ed. Aerodynamics for Engineering Students (5th ed.). ISBN 0-7506-5111-3.

- ↑ Kármán, Theodore von (1954). Cornell University Press (reproduced by Dover in 2004), ed. Aerodynamics: Selected Topics in the Light of their Historical Development. ISBN 0-486-43485-0.

- ↑ Lanchester, Frederick W. (1907). Constable, ed. Aerodynamics.

- ↑ Prandtl, Ludwig (1918). Königliche Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, ed. Tragflügeltheorie.

- ↑ Abbott, Ira H., and Von Doenhoff, Albert E., Theory of Wing Sections, Section 1.4

- ↑ Clancy, L.J., Aerodynamics, Section 8.11

- ↑ Sydney University's Aerodynamics for Students (pdf)

- ↑ Aerospace Web's explanation of lift coefficient

- ↑ Abbott, Ira H., and Von Doenhoff, Albert E., Theory of Wing Sections, Section 1.3

- ↑ Clancy, L.J., Aerodynamics, Equation 5.7

References

- Clancy, L.J. (1975), Aerodynamics, Pitman Publishing Limited, London. ISBN 0-273-01120-0

- Abbott, Ira H., and Von Doenhoff, Albert E. (1959), Theory of Wing Sections, Dover Publications Inc., New York. Standard Book Number 486-60586-8

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)