Liberal democracy

| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

| Basic forms |

| Variants |

|

| Politics portal |

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | ||||||||||

| Power source | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

Academic disciplines |

|

Organs of government |

|

Related topics

|

|

Subseries |

| Politics portal |

Liberal democracy is a form of government in which representative democracy operates under the principles of liberalism, i.e. protecting the rights of the individual, which are generally enshrined in law. It is characterised by fair, free, and competitive elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into different branches of government, the rule of law in everyday life as part of an open society, and the equal protection of human rights, civil rights, civil liberties, and political freedoms for all persons. To define the system in practice, liberal democracies often draw upon a constitution, either formally written or uncodified, to delineate the powers of government and enshrine the social contract. After a period of sustained expansion throughout the 20th century, liberal democracy became the predominant political system in the world.

A liberal democracy may take various constitutional forms: it may be a constitutional republic, such as France, Germany, India, Ireland, Italy, or the United States, or a constitutional monarchy, such as Japan, Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, or the United Kingdom. It may have a presidential system (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, the United States), a semi-presidential system (France), or a parliamentary system (Australia, Canada, India, Italy, New Zealand, Poland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom).

Liberal democracies usually have universal suffrage, granting all adult citizens the right to vote regardless of race, gender or property ownership. Historically, however, some countries regarded as liberal democracies have had a more limited franchise, and some do not have secret ballots. There may also be qualifications such as voters being required to register before being allowed to vote. The decisions made through elections are made not by all of the citizens, but rather by those who choose to participate by voting.

The liberal democratic constitution defines the democratic character of the state. The purpose of a constitution is often seen as a limit on the authority of the government. Liberal democracy emphasises the separation of powers, an independent judiciary, and a system of checks and balances between branches of government. Liberal democracies are likely to emphasise the importance of the state being a Rechtsstaat that follows the principle of rule of law. Governmental authority is legitimately exercised only in accordance with written, publicly disclosed laws adopted and enforced in accordance with established procedure. Many democracies use federalism—also known as vertical separation of powers—in order to prevent abuse and increase public input by dividing governing powers between municipal, provincial and national governments (e.g., Germany where the federal government assumes the main legislative responsibilities and the federated Länder assume many executive tasks).

Rights and freedoms

In practice, democracies do have limits on certain freedoms. There are various legal limitations such as copyright and laws against defamation. There may be limits on anti-democratic speech, on attempts to undermine human rights, and on the promotion or justification of terrorism. In the United States more than in Europe, during the Cold War, such restrictions applied to Communists. Now they are more commonly applied to organisations perceived as promoting actual terrorism or the incitement of group hatred. Examples include anti-terrorism legislation, the shutting down of Hezbollah satellite broadcasts, and some laws against hate speech. Critics claim that these limitations may go too far and that there may be no due and fair judicial process.

The common justification for these limits is that they are necessary to guarantee the existence of democracy, or the existence of the freedoms themselves. For example, allowing free speech for those advocating mass murder undermines the right to life and security. Opinion is divided on how far democracy can extend to include the enemies of democracy in the democratic process. If relatively small numbers of people are excluded from such freedoms for these reasons, a country may still be seen as a liberal democracy. Some argue that this is only quantitatively (not qualitatively) different from autocracies that persecute opponents, since only a small number of people are affected and the restrictions are less severe. Others emphasise that democracies are different. At least in theory, opponents of democracy are also allowed due process under the rule of law. In principle, democracies allow criticism and change of the leaders and the political and economic system itself; it is only attempts to do so violently and the promotion of such violence that is prohibited.

However, many governments considered to be democratic have restrictions upon expressions considered anti-democratic, such as Holocaust denial and hate speech. Members of political organisations with connections to prior totalitarianism (typically Soviet-style-Communist or fascist National Socialists) parties prohibited any current or former members of such organisations may be deprived of the vote and the privilege of holding certain jobs. Discriminatory behaviour may be prohibited, such as refusal by owners of public accommodations to serve persons on grounds of race, religion, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation. For example, in Canada, a printer who refused to print materials for the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives was fined $5,000, incurred $100,000 in legal fees, and was ordered to pay a further $40,000 of his opponents' legal fees by the Human Rights Tribunal.[1]

Other rights considered fundamental in one country may be foreign to other governments. For instance, the constitutions of Canada, India, Israel, Mexico and the United States guarantee freedom from double jeopardy, a right not provided in other legal systems. Similarly, many Americans consider gun rights to be important, while other countries do not recognise them as fundamental rights.

Preconditions

Although they are not part of the system of government as such, a modicum of individual and economic freedoms, which result in the formation of a significant middle class and a broad and flourishing civil society, are often seen as pre-conditions for liberal democracy (Lipset 1959).

For countries without a strong tradition of democratic majority rule, the introduction of free elections alone has rarely been sufficient to achieve a transition from dictatorship to democracy; a wider shift in the political culture and gradual formation of the institutions of democratic government are needed. There are various examples—for instance, in Latin America—of countries that were able to sustain democracy only temporarily or in a limited fashion until wider cultural changes established the conditions under which democracy could flourish.

One of the key aspects of democratic culture is the concept of a "loyal opposition", where political competitors may disagree, but they must tolerate one another and acknowledge the legitimate and important roles that each play. This is an especially difficult cultural shift to achieve in nations where transitions of power have historically taken place through violence. The term means, in essence, that all sides in a democracy share a common commitment to its basic values. The ground rules of the society must encourage tolerance and civility in public debate. In such a society, the losers accept the judgment of the voters when the election is over, and allow for the peaceful transfer of power. The losers are safe in the knowledge that they will neither lose their lives nor their liberty, and will continue to participate in public life. They are loyal not to the specific policies of the government, but to the fundamental legitimacy of the state and to the democratic process itself.

Origins

Liberal democracy traces its origins—and its name—to the European 18th-century, also known as the Age of Enlightenment. At the time, the vast majority of European states were monarchies, with political power held either by the monarch or the aristocracy. The possibility of democracy had not been a seriously considered political theory since classical antiquity, and the widely held belief was that democracies would be inherently unstable and chaotic in their policies due to the changing whims of the people. It was further believed that democracy was contrary to human nature, as human beings were seen to be inherently evil, violent and in need of a strong leader to restrain their destructive impulses. Many European monarchs held that their power had been ordained by God, and that questioning their right to rule was tantamount to blasphemy.[2]

These conventional views were challenged at first by a relatively small group of Enlightenment intellectuals, who believed that human affairs should be guided by reason and principles of liberty and equality. They argued that all people are created equal, and therefore political authority cannot be justified on the basis of "noble blood", a supposed privileged connection to God, or any other characteristic that is alleged to make one person superior to others. They further argued that governments exist to serve the people, not vice versa, and that laws should apply to those who govern as well as to the governed (a concept known as rule of law). Some of these ideas began to be expressed in the English Bill of Rights 1689.[3][4]

By the late 18th century, leading philosophers of the day had published works that spread around the European continent and beyond. These ideas and beliefs inspired the American Revolution and the French Revolution, which gave birth to the ideology of liberalism and instituted forms of government that attempted to apply the principles of the Enlightenment philosophers into practice. Neither of these forms of government was precisely what we would call a liberal democracy we know today (the most significant differences being that voting rights were still restricted to a minority of the population and slavery remained a legal institution), and the French attempt turned out to be short-lived, but they were the prototypes from which liberal democracy later grew. Since the supporters of these forms of government were known as liberals, the governments themselves came to be known as liberal democracies.

When the first prototypical liberal democracies were founded, the liberals themselves were viewed as an extreme and rather dangerous fringe group that threatened international peace and stability. The conservative monarchists who opposed liberalism and democracy saw themselves as defenders of traditional values and the natural order of things, and their criticism of democracy seemed vindicated when Napoleon Bonaparte took control of the young French Republic, reorganised it into the first French Empire and proceeded to conquer most of Europe. Napoleon was eventually defeated and the Holy Alliance was formed in Europe to prevent any further spread of liberalism or democracy. However, liberal democratic ideals soon became widespread among the general population, and, over the 19th century, traditional monarchy was forced on a continuous defensive and withdrawal.

The dominions of the British Empire became laboratories for liberal democracy from the mid 19th century onward. In Canada, responsible government began in the 1840s and in Australia and New Zealand, parliamentary government elected by male suffrage and secret ballot was established from the 1850s and female suffrage achieved from the 1890s.[5]

Reforms and revolutions helped move most European countries towards liberal democracy. Liberalism ceased being a fringe opinion and joined the political mainstream. At the same time, a number of non-liberal ideologies developed that took the concept of liberal democracy and made it their own. The political spectrum changed; traditional monarchy became more and more a fringe view and liberal democracy became more and more mainstream. By the end of the 19th century, liberal democracy was no longer only a "liberal" idea, but an idea supported by many different ideologies. After World War I and especially after World War II, liberal democracy achieved a dominant position among theories of government and is now endorsed by the vast majority of the political spectrum.

Although liberal democracy was originally put forward by Enlightenment liberals, the relationship between democracy and liberalism has been controversial since the beginning. The ideology of liberalism—particularly in its classical form—is highly individualistic and concerns itself with limiting the power of the state over the individual. In contrast, democracy is seen by some as a collectivist ideal, concerned with empowering the masses. Thus, liberal democracy may be seen as a compromise between liberal individualism and democratic collectivism. Those who hold this view sometimes point to the existence of illiberal democracy and liberal autocracy as evidence that constitutional liberalism and democratic government are not necessarily interconnected. On the other hand, there is the view that constitutional liberalism and democratic government are not only compatible but necessary for the true existence of each other, both arising from the underlying concept of political equality. The research institute Freedom House today simply defines liberal democracy as an electoral democracy also protecting civil liberties.

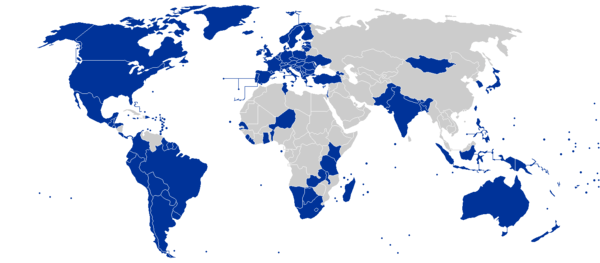

Liberal democracies around the world

Several organisations and political scientists maintain lists of free and unfree states, both in the present and going back a couple centuries. Of these, the best known may be the Polity Data Set[9] and that produced by Freedom House.

There is agreement amongst several intellectuals and organisations such as Freedom House that the states of the European Union, Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, Japan, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, South Korea, Taiwan, the United States, India, Canada,[10][11][12][13][14] Mexico, Israel, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand[15] are liberal democracies, with Canada having the largest land area and India currently having the largest population among the democracies in the world.[16]

Freedom House considers many of the officially democratic governments in Africa and the former Soviet Union to be undemocratic in practice, usually because the sitting government has a strong influence over election outcomes. Many of these countries are in a state of considerable flux.

Officially non-democratic forms of government, such as single-party states and dictatorships are more common in East Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa.

Types

Proportional vs. plurality representation

Plurality voting system award seats according to regional majorities. The political party or individual candidate who receives the most votes, wins the seat which represents that locality. There are other democratic electoral systems, such as the various forms of proportional representation, which award seats according to the proportion of individual votes that a party receives nation-wide or in a particular region.

One of the main points of contention between these two systems, is whether to have representatives who are able to effectively represent specific regions in a country, or to have all citizens' vote count the same, regardless of where in the country they happen to live.

Some countries such as Germany and New Zealand, address the conflict between these two forms of representation, by having two categories of seats in the lower house of their national legislative bodies. The first category of seats is appointed according to regional popularity, and the remainder are awarded to give the parties a proportion of seats that is equal—or as equal as practicable—to their proportion of nation-wide votes. This system is commonly called mixed member proportional representation.

Australia incorporates both systems in having the preferential voting system applicable to the lower house and proportional representation by state in the upper house. This system is argued to result in a more stable government, while having a better diversity of parties to review its actions.

Presidential vs. parliamentary systems

A presidential system is a system of government of a republic in which the executive branch is elected separately from the legislative. A parliamentary system is distinguished by the executive branch of government being dependent on the direct or indirect support of the parliament, often expressed through a vote of confidence.

The presidential system of democratic government has become popular in Latin America, Africa, and parts of the former Soviet Union, largely by the example of the United States. Constitutional monarchies (dominated by elected parliaments) are popular in Northern Europe and some former colonies which peacefully separated, such as Australia and Canada. Others have also arisen in Spain, East Asia, and a variety of small nations around the world. Former British territories such as South Africa, India, Ireland, and the United States opted for different forms at the time of independence. The parliamentary system is popular in the European Union and neighboring countries.

Issues and criticism

Lacking direct democracy

As liberal democracy is a variant of representative democracy, it does not directly respect the will of average citizens except when citizens elect representatives. Given this that a small number of elected representatives make decisions and policies about how a nation is governed, the laws that govern the lives of its citizens, elite theorists such as Robert Michels argue that representative democracy and thereby liberal democracy is merely a decoration over an oligarchy;[17] political theorist Robert A. Dahl has described liberal democracies as polyarchies. For these reasons and others, opponents support other, more direct forms of governance such as direct democracy.

It has generally been argued by those who support liberal democracy or representative democracy that minority interests and individual liberties must be protected from the majority; for instance in Federalist No. 10 James Madison states, "the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property. Those who hold and those who are without property have ever formed distinct interests in society." In order to prevent a minority, in this case, land owners, from being marginalised by a majority, in this case non-land owners, it prescribes what it calls a republic. Unmoderated majority rule could, in this view, lead to an oppression of minorities (see Majoritarianism below.) Another argument is that the elected leaders may be more interested and able than the average voter. A third is that it takes much effort and time if everyone should gather information, discuss, and vote on most issues. Direct democracy proponents in turn have counter-arguments, see the Direct democracy. Switzerland is a functioning example of direct democracy.

Today, Many liberal democracies have elements of direct democracy such as referendums, plebiscites, initiatives, recall elections, and models of "Deliberative democracy". For example, former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez recently allowed referendums on important aspects of the government. Also, several states in the United States have functional aspects that are directly democratic. Uruguay is another example. Many other countries have referendums to a lesser degree in their political system.

Dictatorship of the bourgeoisie

Some Marxists, Communists, Socialists and anarchists, argue that liberal democracy, under capitalist ideology, is constitutively class-based and therefore can never be democratic or participatory. It is referred to as bourgeois democracy because ultimately politicians fight only for the rights of the bourgeoisie. According to Marx, representation of the interests of different classes is proportional to the influence which the economic clout that a particular class can purchase (through bribes, transmission of propaganda, economic blackmail, campaign 'donations', etc.). Thus, the public interest, in so-called liberal democracies, is systematically corrupted by the wealth of those classes rich enough to gain (the appearance of) representation. Because of this, multi-party democracies under capitalist ideology are always distorted and anti-democratic, their operation merely furthering the class interests of the owners of the means of production.

According to Marx, the bourgeois class becomes wealthy through a drive to appropriate the surplus-value of the creative labours of the working class. This drive obliges the bourgeois class to amass ever-larger fortunes by increasing the proportion of surplus-value by exploiting the working class through capping workers' terms and conditions as close to poverty levels as possible. (Incidentally, this obligation demonstrates the clear limit to bourgeois freedom, even for the bourgeoisie itself.)

Thus, according to Marx, parliamentary elections are no more than a cynical, systemic attempt to deceive the people by permitting them, every now and again, to endorse one or other of the bourgeoisie's predetermined choices of which political party can best advocate the interests of capital. Once elected, this parliament, as a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, enacts regulations that actively support the interests of its true constituency, the bourgeoisie (such as bailing out Wall St investment banks; direct socialisation/subsidisation of business - GMH, US/European agricultural subsidies; and even wars to guarantee trade in commodities such as oil).

Vladimir Lenin once argued that liberal democracy had simply been used to give an illusion of democracy while maintaining the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie.

In short, popular elections are nothing but the appearance of having the power of decision of who among the ruling classes will misrepresent the people in parliament.[18]

The cost of political campaigning in representative democracies favors the rich, a form of plutocracy where only a very small number of individuals can actually affect government policy. In Athenian democracy, some public offices were randomly allocated to citizens, in order to inhibit the effects of plutocracy. Aristotle described the law courts in Athens which were selected by lot as democratic[19] and described elections as oligarchic.[20]

Liberal democracy has also been attacked by some socialists as a dishonest farce used to keep the masses from realizing that their will is irrelevant in the political process, while at the same time a conspiracy for making them restless for some political agenda. Some contend that it encourages candidates to make deals with wealthy supporters, offering favorable legislation if the candidate is elected—perpetuating conspiracies for monopolisation of key areas. Campaign finance reform is an attempt to correct this perceived problem.

In response to these claims, United States economist Steven Levitt argues in his book Freakonomics that campaign spending is no guarantee of electoral success. He compared electoral success of the same pair of candidates running against one another repeatedly for the same job, as often happens in United States Congressional elections, where spending levels varied. He concludes:

- "A winning candidate can cut his spending in half and lose only 1 percent of the vote. Meanwhile, a losing candidate who doubles his spending can expect to shift the vote in his favor by only that same 1 percent."[21]

It might be said that Levitt's response misses the Socialist point, which is that citizens who have little to no money at all are blocked from political office entirely. This argument is not refuted merely by noting that either doubling or halving of electoral spending will only shift a given candidate's chances of winning by 1 percent. However, whether this constitutes a strong criticism of liberal democracy is not clear. The Social Democratic point is that, while there is no de jure limitations on the poor standing for office, there are de facto limitations. But, if to be insufficiently wealthy to pursue political office is not different from being actively prevented from doing so by law, then it is not clear that other practical impediments, even ones such as muteness or stupidity, do not similarly qualify as arbitrary restrictions on democratic freedom.

Media

Critics of the role of the media in liberal democracies allege that concentration of media ownership leads to major distortions of democratic processes. In Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky argue, via their Propaganda Model[22] that the corporate media limits the availability of contesting views, and assert this creates a narrow spectrum of elite opinion. This is a natural consequence, they say, of the close ties between powerful corporations and the media and thus limited and restricted to the explicit views of those who can afford it.[23]

Media commentators also point out that the influential early champions of the media industry held fundamentally anti-democratic views, opposing the general population's involvement in creating policy.[24] Walter Lippmann writing in The Phantom Public (1925), sought to "put the public in its place" so that those in power would be "free of the trampling and roar of a bewildered herd,"[25] while Edward Bernays, originator of public relations, sought to "regiment the public mind every bit as much as an army regiments their bodies."[26]

Defenders responding to such arguments assert that constitutionally protected freedom of speech makes it possible for both for-profit and non-profit organisations to debate the issues. They argue that media coverage in democracies simply reflects public preferences, and does not entail censorship. Especially with new forms of media such as the Internet, it is not expensive to reach a wide audience, if there is an interest for the ideas presented.

Limited voter turnout

Low voter turnout, whether the cause is disenchantment, indifference or contentment with the status quo, may be seen as a problem, especially if disproportionate in particular segments of the population. Although turnout levels vary greatly among modern democratic countries, and in various types and levels of elections within countries, at some point low turnout may prompt questions as to whether the results reflect the will of the people, whether the causes may be indicative of concerns to the society in question, or in extreme cases the legitimacy of the electoral system.

Get out the vote campaigns, either by governments or private groups, may increase voter turnout, but distinctions must be made between general campaigns to raise the turnout rate and partisan efforts to aid a particular candidate, party or cause.

Several nations have forms of compulsory voting, with various degrees of enforcement. Proponents argue that this increases the legitimacy, and thus also popular acceptance, of the elections and ensures political participation by all those affected by the political process, and reduces the costs associated with encouraging voting. Arguments against include restriction of freedom, economic costs of enforcement, increased number of invalid and blank votes, and random voting.[27]

Other alternatives include increased use of absentee ballots, or other measures to ease or improve the ability to vote, including Electronic voting.

Ethnic and religious conflicts

For historical reasons, many states are not culturally and ethnically homogeneous. There may be sharp ethnic, linguistic, religious and cultural divisions. In fact, some groups may be actively hostile to each other. A democracy, which by definition allows mass participation in decision-making theoretically also allows the use of the political process against 'enemy' groups.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the partial democratisation of Soviet bloc states was followed by wars in the former Yugoslavia, in the Caucasus, and in Moldova. Nevertheless, some people believe that the fall of Communism and the increase in the number of democratic states were accompanied by a sudden and dramatic decline in total warfare, interstate wars, ethnic wars, revolutionary wars, and the number of refugees and displaced people (worldwide, not in the countries of the former sovietic bloc). This trend, however, can be attributed to the end of cold war and the natural exhaustion of said conflicts, many of which were fueled by the USA and the USSR[28] See also the section below on Majoritarianism and Democratic peace theory.

In her book World on Fire, Yale Law School professor Amy Chua posits that "when free market democracy is pursued in the presence of a market-dominant minority, the almost invariable result is backlash. This backlash typically takes one of three forms. The first is a backlash against markets, targeting the market-dominant minority's wealth. The second is a backlash against democracy by forces favorable to the market-dominant minority. The third is violence, sometimes genocidal, directed against the market-dominant minority itself.".[29]

Bureaucracy

A persistent libertarian and monarchist critique of democracy is the claim that it encourages the elected representatives to change the law without necessity, and in particular to pour forth a flood of new laws (as described in Herbert Spencer's The Man versus the State). This is seen as pernicious in several ways. New laws constrict the scope of what were previously private liberties. Rapidly changing laws make it difficult for a willing non-specialist to remain law-abiding. This may be an invitation for law-enforcement agencies to misuse power. The claimed continual complication of the law may be contrary to a claimed simple and eternal natural law—although there is no consensus on what this natural law is, even among advocates. Supporters of democracy point to the complex bureaucracy and regulations that has occurred in dictatorships, like many of the former Communist states.

The bureaucracy in Liberal democracies is often criticised for a claimed slowness and complexity of their decision-making. The term "Red tape" is a synonym of slow bureaucratic functioning that hinders quick results in a liberal democracy.

Short-term focus

Modern liberal democracies, by definition, allow for regular changes of government. That has led to a common criticism of their short-term focus. In four or five years the government will face a new election, and it must think of how it will win that election. That would encourage a preference for policies that will bring short term benefits to the electorate (or to self-interested politicians) before the next election, rather than unpopular policy with longer term benefits. This criticism assumes that it is possible to make long term predictions for a society, something Karl Popper has criticised as historicism.

Besides the regular review of governing entities, short-term focus in a democracy could also be the result of collective short-term thinking. For example, consider a campaign for policies aimed at reducing environmental damage while causing temporary increase in unemployment. However, this risk applies also to other political systems.

Anarcho-capitalist Hans-Herman Hoppe explained short-termism of the democratic governments by the rational choice of currently ruling group to over exploit temporarily accessible resources, thus deriving maximal economic advantage to the members of this group. (He contrasted this with hereditary monarchy, in which a monarch has an interest in preserving the long-term capital value of his property (i.e. the country he owns) counterbalancing his desire to extract immediate revenue. He argues that the historical record of levels of taxation in certain monarchies (20-25%)[30] and certain liberal democracies (30–60%) seems to confirm this contention.[31]

Public choice theory

Public choice theory is a branch of economics that studies the decision-making behaviour of voters, politicians and government officials from the perspective of economic theory. One studied problem is that each voter has little influence and may therefore have a rational ignorance regarding political issues. This may allow special interest groups to gain subsidies and regulations beneficial to them but harmful to society. However, special interest groups may be equally or more influential in nondemocracies.

Majoritarianism

The tyranny of the majority is the fear that a direct democratic government, reflecting the majority view, can take action that oppresses a particular minority; for instance a minority holding wealth, property ownership, or power (see Federalist No. 10). Theoretically, the majority is a majority of all citizens. If citizens are not compelled by law to vote it is usually a majority of those who choose to vote. If such of group constitutes a minority then it is possible that a minority could, in theory, oppress another minority in the name of the majority. However, such an argument could apply to both direct democracy or representative democracy. In comparison to a direct democracy where every citizen is forced to vote, under liberal democracies the wealth and power is usually concentrated in the hands of a small privileged class who have significant power over the political process (See inverted totalitarianism). It is argued by some that in representative democracies this minority makes the majority of the policies and potentially oppresses the minority or even the majority in the name of the majority (see Silent majority). Several de facto dictatorships also have compulsory, but not "free and fair", voting in order to try to increase the legitimacy of the regime.

Possible examples of a minority being oppressed by or in the name of the majority:

- Those potentially subject to conscription are a minority possibly because of socioeconomic reasons.

- The minority who are wealthy often use their money and influence to manipulate the political process against the interests of the rest of the population, who are the minority in terms of income and access.

- Several European countries have introduced bans on personal religious symbols in state schools. Opponents see this as a violation of rights to freedom of religion. Supporters see it as following from the separation of state and religious activities.

- Prohibition of pornography is typically determined by what the majority is prepared to accept.

- The private possession of various weapons (i.e. batons, nunchakus, brass knuckles, pepper spray, firearms etc...) is arbitrarily criminalized in several democracies (i.e. the United Kingdom, Belgium, etc...), with such arbitrary criminalization often being motivated by moralism, racism, classism and/or paternalism.

- Recreational drug, caffeine, tobacco and alcohol use is too often criminalised or otherwise suppressed by majorities, originally for racist, classist, religious or paternalistic motives.[32][33][34][35]

- Society's treatment of homosexuals is also cited in this context. Homosexual acts were widely criminalised in democracies until several decades ago; in some democracies they still are, reflecting the religious or sexual mores of the majority.

- The Athenian democracy and the early United States had slavery.

- The majority often taxes the minority who are wealthy at progressively higher rates, with the intention that the wealthy will incur a larger tax burden for social purposes.

- In prosperous western representative democracies, the poor form a minority of the population, and may not have the power to use the state to initiate redistribution when a majority of the electorate opposes such designs. When the poor form a distinct underclass, the majority may use the democratic process to, in effect, withdraw the protection of the state.

- An often quoted example of the 'tyranny of the majority' is that Adolf Hitler came to power by legitimate democratic procedures. The Nazi party gained the largest share of votes in the democratic Weimar republic in 1933. Some might consider this an example of "tyranny of a minority" since he never gained a majority vote, but it is common for a plurality to exercise power in democracies, so the rise of Hitler cannot be considered irrelevant. However, his regime's large-scale human rights violations took place after the democratic system had been abolished. Also, the Weimar constitution in an "emergency" allowed dictatorial powers and suspension of the essentials of the constitution itself without any vote or election.

Proponents of democracy make a number of defenses concerning 'tyranny of the majority'. One is to argue that the presence of a constitution protecting the rights of all citizens in many democratic countries acts as a safeguard. Generally, changes in these constitutions require the agreement of a supermajority of the elected representatives, or require a judge and jury to agree that evidentiary and procedural standards have been fulfilled by the state, or two different votes by the representatives separated by an election, or, sometimes, a referendum. These requirements are often combined. The separation of powers into legislative branch, executive branch, judicial branch also makes it more difficult for a small majority to impose their will. This means a majority can still legitimately coerce a minority (which is still ethically questionable), but such a minority would be very small and, as a practical matter, it is harder to get a larger proportion of the people to agree to such actions.

Another argument is that majorities and minorities can take a markedly different shape on different issues. People often agree with the majority view on some issues and agree with a minority view on other issues. One's view may also change. Thus, the members of a majority may limit oppression of a minority since they may well in the future themselves be in a minority.

A third common argument is that, despite the risks, majority rule is preferable to other systems, and the tyranny of the majority is in any case an improvement on a tyranny of a minority. All the possible problems mentioned above can also occur in nondemocracies with the added problem that a minority can oppress the majority. Proponents of democracy argue that empirical statistical evidence strongly shows that more democracy leads to less internal violence and mass murder by the government. This is sometimes formulated as Rummel's Law, which states that the less democratic freedom a people have, the more likely their rulers are to murder them.

Political stability

One argument for democracy is that by creating a system where the public can remove administrations, without changing the legal basis for government, democracy aims at reducing political uncertainty and instability, and assuring citizens that however much they may disagree with present policies, they will be given a regular chance to change those who are in power, or change policies with which they disagree. This is preferable to a system where political change takes place through violence.

Some think that political stability may be considered as excessive when the group in power remains the same for an extended period of time. On the other hand, this is more common in nondemocracies.

One notable feature of liberal democracies is that their opponents (those groups who wish to abolish liberal democracy) rarely win elections. Advocates use this as an argument to support their view that liberal democracy is inherently stable and can usually only be overthrown by external force, while opponents argue that the system is inherently stacked against them despite its claims to impartiality. In the past, it was feared that democracy could be easily exploited by leaders with dictatorial aspirations, who could get themselves elected into power. However, the actual number of liberal democracies that have elected dictators into power is low. When it has occurred, it is usually after a major crisis has caused many people to doubt the system or in young/poorly functioning democracies. Some possible examples include Adolf Hitler during the Great Depression and Napoleon III, who became first President of the Second French Republic and later Emperor.

Effective response in wartime

A liberal democracy, by definition, implies that power is not concentrated. One criticism is that this could be a disadvantage for a state in wartime, when a fast and unified response is necessary. The legislature usually must give consent before the start of an offensive military operation, although sometimes the executive can do this on its own while keeping the legislature informed. If the democracy is attacked, then no consent is usually required for defensive operations. The people may vote against a conscription army.

However, actual research shows that democracies are more likely to win wars than non-democracies. One explanation attributes this primarily to "the transparency of the polities, and the stability of their preferences, once determined, democracies are better able to cooperate with their partners in the conduct of wars". Other research attributes this to superior mobilisation of resources or selection of wars that the democratic states have a high chance of winning.[36]

Stam and Reiter also note that the emphasis on individuality within democratic societies means that their soldiers fight with greater initiative and superior leadership.[37] Officers in dictatorships are often selected for political loyalty rather than military ability. They may be exclusively selected from a small class or religious/ethnic group that support the regime. The leaders in nondemocracies may respond violently to any perceived criticisms or disobedience. This may make the soldiers and officers afraid to raise any objections or do anything without explicit authorisation. The lack of initiative may be particularly detrimental in modern warfare. Enemy soldiers may more easily surrender to democracies since they can expect comparatively good treatment. In contrast, Nazi Germany killed almost 2/3 of the captured Soviet soldiers, and 38% of the American soldiers captured by North Korea in the Korean War were killed.

Better information on and corrections of problems

A democratic system may provide better information for policy decisions. Undesirable information may more easily be ignored in dictatorships, even if this undesirable or contrarian information provides early warning of problems. The democratic system also provides a way to replace inefficient leaders and policies. Thus, problems may continue longer and crises of all kinds may be more common in autocracies.[38]

Corruption

Research by the World Bank suggests that political institutions are extremely important in determining the prevalence of corruption: (long term) democracy, parliamentary systems, political stability, and freedom of the press are all associated with lower corruption.[39] Freedom of information legislation is important for accountability and transparency. The Indian Right to Information Act "has already engendered mass movements in the country that is bringing the lethargic, often corrupt bureaucracy to its knees and changing power equations completely."[40]

Terrorism

Several studies have concluded that terrorism is most common in nations with intermediate political freedom; meaning countries transitioning from autocratic governance to democracy. Nations with strong autocratic governments and governments that allow for more political freedom experience less terrorism.[41]

Economic growth and financial crises

Statistically, more democracy correlates with a higher gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

However, there is disagreement regarding how much credit the democratic system can take for this. One observation is that democracy became widespread only after the industrial revolution and the introduction of capitalism. On the other hand, the industrial revolution started in England which was one of the most democratic nations for its time within its own borders. (But this democracy was very limited and did not apply to the colonies which contributed significantly to the wealth.)

Several statistical studies support the theory that more capitalism, measured for example with one the several Indices of Economic Freedom which has been used in hundreds of studies by independent researchers,[42] increases economic growth and that this in turn increases general prosperity, reduces poverty, and causes democratisation. This is a statistical tendency, and there are individual exceptions like Mali, which is ranked as "Free" by Freedom House but is a Least Developed Country, or Qatar, which has arguably the highest GDP per capita in the world but has never been democratic. There are also other studies suggesting that more democracy increases economic freedom although a few find no or even a small negative effect.[43][44][45][46][47][48] One objection might be that nations like Sweden and Canada today score just below nations like Chile and Estonia on economic freedom but that Sweden and Canada today have a higher GDP per capita. However, this is a misunderstanding, the studies indicate effect on economic growth and thus that future GDP per capita will be higher with higher economic freedom. Also, according to the index, Sweden and Canada are among the world's most capitalist nations, due to factors such as strong rule of law, strong property rights, and few restrictions against free trade. Critics might argue that the Index of Economic Freedom and other methods used does not measure the degree of capitalism, preferring some other definition.

Some argue that economic growth due to its empowerment of citizens, will ensure a transition to democracy in countries such as Cuba. However, other dispute this. Even if economic growth has caused democratisation in the past, it may not do so in the future. Dictators may now have learned how to have economic growth without this causing more political freedom.[49]

A high degree of oil or mineral exports is strongly associated with nondemocratic rule. This effect applies worldwide and not only to the Middle East. Dictators who have this form of wealth can spend more on their security apparatus and provide benefits which lessen public unrest. Also, such wealth is not followed by the social and cultural changes that may transform societies with ordinary economic growth.[50]

A recent meta-analysis finds that democracy has no direct effect on economic growth. However, it has a strong and significant indirect effects which contribute to growth. Democracy is associated with higher human capital accumulation, lower inflation, lower political instability, and higher economic freedom. There is also some evidence that it is associated with larger governments and more restrictions on international trade.[51]

If leaving out East Asia, then during the last forty-five years poor democracies have grown their economies 50% more rapidly than nondemocracies. Poor democracies such as the Baltic countries, Botswana, Costa Rica, Ghana, and Senegal have grown more rapidly than nondemocracies such as Angola, Syria, Uzbekistan, and Zimbabwe.[38]

Of the eighty worst financial catastrophes during the last four decades, only five were in democracies. Similarly, poor democracies are half likely as nondemocracies to experience a 10 percent decline in GDP per capita over the course of a single year.[38]

Famines and refugees

A prominent economist, Amartya Sen, has noted that no functioning democracy has ever suffered a large scale famine.[52] Refugee crises almost always occur in nondemocracies. Looking at the volume of refugee flows for the last twenty years, the first eighty-seven cases occurred in autocracies.[38]

Human development

Democracy correlates with a higher score on the human development index and a lower score on the human poverty index.

Democracies have the potential to put in place better education, longer life expectancy, lower infant mortality, access to drinking water, and better health care than dictatorships. This is not due to higher levels of foreign assistance or spending a larger percentage of GDP on health and education. Instead, the available resources are managed better.[38]

Several health indicators (life expectancy and infant and maternal mortality) have a stronger and more significant association with democracy than they have with GDP per capita, rise of the public sector, or income inequality.[53]

In the post-Communist nations, after an initial decline, those that are the most democratic have achieved the greatest gains in life expectancy.[54]

Democratic peace theory

Numerous studies using many different kinds of data, definitions, and statistical analyses have found support for the democratic peace theory. The original finding was that liberal democracies have never made war with one another. More recent research has extended the theory and finds that democracies have few Militarized Interstate Disputes causing less than 1000 battle deaths with one another, that those MIDs that have occurred between democracies have caused few deaths, and that democracies have few civil wars.[55] There are various criticisms of the theory, including specific historic wars and that correlation is not causation.

Mass murder by government

Research shows that the more democratic nations have much less democide or murder by government.[56] Similarly, they have less genocide and politicide.[57]

Freedoms and rights

The freedoms and rights of the citizens in liberal democracies are usually seen as beneficial.

See also

References

- ↑ "Christian Business Ordered to Duplicate Homosexual Activist". Concerned Women for America. Archived from the original on 2008-11-28.

- ↑ Divine right of kings

- ↑ "Rise of Parliament". The National Archives. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "Constitutionalism: America & Beyond". Bureau of International Information Programs (IIP), U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

The earliest, and perhaps greatest, victory for liberalism was achieved in England. The rising commercial class that had supported the Tudor monarchy in the 16th century led the revolutionary battle in the 17th, and succeeded in establishing the supremacy of Parliament and, eventually, of the House of Commons. What emerged as the distinctive feature of modern constitutionalism was not the insistence on the idea that the king is subject to law (although this concept is an essential attribute of all constitutionalism). This notion was already well established in the Middle Ages. What was distinctive was the establishment of effective means of political control whereby the rule of law might be enforced. Modern constitutionalism was born with the political requirement that representative government depended upon the consent of citizen subjects.... However, as can be seen through provisions in the 1689 Bill of Rights, the English Revolution was fought not just to protect the rights of property (in the narrow sense) but to establish those liberties which liberals believed essential to human dignity and moral worth. The "rights of man" enumerated in the English Bill of Rights gradually were proclaimed beyond the boundaries of England, notably in the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 and in the French Declaration of the Rights of Man in 1789.

- ↑ Geoffrey Blainey; A Very Short History of the World; Penguin Books; 2004; ISBN 978-0-14-300559-9

- ↑ http://polisci.la.psu.edu/faculty/Casper/caspertufisPAweb.pdf Polisci.la.psu.edu

- ↑ Bollen, K.A. (1992) Political Rights and Political Liberties in Nations: An Evaluation of Human Rights Measures, 1950 to 1984. In: Jabine, T.B. and Pierre Claude, R. "Human Rights and Statistics". University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3108-2

- ↑ Freedom in The World 2015 (PDF)

- ↑ Policy Data Set

- ↑ Seyla Benhabib, Democracy and difference: contesting the boundaries of the political

- ↑ Alain Gagnon,Intellectuals in liberal democracies: political influence and social involvement

- ↑ Yvonne Schmidt, Foundations of Civil and Political Rights in Israel and the Occupied Territories

- ↑ William S. Livingston, A Prospect of purple and orange democracy

- ↑ Steven V. Mazie,Israel's higher law: religion and liberal democracy in the Jewish state

- ↑ Mulgan, Richard; Peter Aimer (2004). "chapter 1, page 17". Politics in New Zealand (3rd ed.). Auckland University Press. pp. 344 pages. ISBN 1-86940-318-5. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ↑ India Awakens, Time

- ↑ James L. Hyland. Democratic theory: the philosophical foundations. Manchester, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Manchester University Press ND, 1995. p. 247.

- ↑ Karl Marx. The civil war in France

- ↑ Aristotle, Politics 2.1273b

- ↑ Aristotle, Politics 4.1294b

- ↑ Levitt, Steven; Dubner, Stephen J. (2006). Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything. HarperCollins. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-06-124513-8.

- ↑ Edward S. Herman "The Propaganda Model Revisited", Monthly Review, July 1996, as reproduced on the Chomsky.info website

- ↑ James Curran and Jean Seaton Power Without Responsibility: the Press and Broadcasting in Britain, London: Routledge, 1997, p.1

- ↑ Noam Chomsky and Gabor Steingart "The United States Has Essentially a One-Party System", Der Spiegel Online, 10 October 2008, as reproduced on the Chomsky.info website

- ↑ Lippmann cited by Henry Beissel "Mutation or Demise: The Democratization of Democracy" Living with Democracy, #155, Winter 2005, as reproduced on the Humanist Persrpectives website

- ↑ Propaganda by Edward Bernays (1928). Historyisaweapon.com. Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ↑ "International IDEA | Compulsory Voting". Idea.int. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ↑ Peace and Conflict 2005: A Global Survey of Armed Conflicts, Self-Determination Movements, and Democracy. Monty G. Marshall and Ted Robert Gurr. Archived February 6, 2007 at the Wayback Machine. For illustrating graphs, see Center for Systemic Peace, (2006). Global Conflict Trends - Measuring Systematic Peace. Retrieved February 19, 2006.

- ↑ Chua, Amy (2002). World on Fire. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-50302-4.

- ↑ Bartlett, Robert (2000). England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings: 1075–1225. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. pp. 165–168. ISBN 0-19-822741-8. 25% tax in England in the 1100s

- ↑ Democracy: The God That Failed (Transaction Publishers, 2001) Paperback (in English) ISBN 0-7658-0868-4

- ↑ David E. Kyvig (1979). Repealing National Prohibition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 6–10. ISBN 0-226-46641-8.

- ↑ Andrew Weil, M.D. and Winifred Rosen (1993). From Chocolate to Morphine. New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-395-66079-3.

Everybody is willing to call certain drugs bad, but there is little agreement from one culture to the next as to which these are. In our own society, all nonmedical drugs other than alcohol, tobacco and caffeine are viewed with suspicion by the majority. ... Some yogis in India use marijuana ritually, but teach that opiates and alcohol are harmful. Muslims may tolerate the use of opium, marijuana and qat ..., but are very strict in their exclusion of alcohol.

- ↑ Joseph McNamara (1994). "Why We Should Call Off the War on Drugs". Questioning Prohibition. Brussels: International Antiprohibitionist League. p. 147.

The drug war has become a race war in which cops, most of them white, arrest non-whites for drug crimes at four to five times the rate whites are arrested.

- ↑ Dr. John Marks (1994). "The Paradox of Prohibition". Questioning Prohibition. Brussels: International Antiprohibitionist League. p. 161.

Havelock Ellis wrote at the turn of the century on his visit to America of the zeal of the Christian missionaries during the 19th century ... In an obscure southwestern state he happened across some upset missionaries who ... had come up against some Amerindians who ate cacti as part of their sacrament much as the Christians use wine. The hallucinogen in the cacti, which the Indians interpreted as putting them in communion with their God, rendered them, said the distraught missionaries, "Resistant to all our moral suasions". The missionaries had recourse to the state legislature and cactus eating was forbidden. Between the turn of the century and the First World War these laws were generalised to all states of the Union and to all substances, including alcohol. The Americans adopted prohibition in response to a strong religious lobby for whom all intoxicants were direct competitors for the control over the minds of men.

- ↑ Ajin Choi, (2004). "Democratic Synergy and Victory in War, 1816–1992". International Studies Quarterly, Volume 48, Number 3, September 2004, pp. 663–682(20). doi:10.1111/j.0020-8833.2004.00319.x

- ↑ Dan, Reiter; Stam, Allan C. (2002). Democracies at War. Princeton University Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 0-691-08948-5.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 "The Democracy Advantage: How Democracies Promote Prosperity and Peace". Carnegie Council. Archived from the original on 2006-06-28.

- ↑ Daniel Lederman, Normal Loaza, Rodrigo Res Soares, (November 2001). "Accountability and Corruption: Political Institutions Matter". World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2708. SSRN 632777. Retrieved February 19, 2006.

- ↑ "Right to Information Act India's magic wand against corruption". AsiaMedia. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ↑ "Harvard Gazette: Freedom squelches terrorist violence". News.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ↑ Free the World. Published Work Using Economic Freedom of the World Research. Retrieved February 19, 2006.

- ↑ Nicclas Bergren, (2002). "The Benefits of Economic Freedom: A Survey" at the Wayback Machine (archived June 28, 2007). Retrieved February 19, 2006.

- ↑ John W. Dawson, (1998). "Review of Robert J. Barro, Determinants of Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Empirical Study". Economic History Services. Retrieved February 19, 2006.

- ↑ W. Ken Farr, Richard A. Lord, J. Larry Wolfenbarger, (1998). "Economic Freedom, Political Freedom, and Economic Well-Being: A Causality Analysis" at the Wayback Machine (archived February 3, 2007). Cato Journal, Vol 18, No 2.

- ↑ Wenbo Wu, Otto A. Davis, (2003). "Economic Freedom and Political Freedom," Encyclopedia of Public Choice. Carnegie Mellon University, National University of Singapore.

- ↑ Ian Vásquez, (2001). "Ending Mass Poverty". Cato Institute. Retrieved February 19, 2006.

- ↑ Susanna Lundström, (April 2002). "The Effects of Democracy on Different Categories of Economic Freedom". Retrieved February 19, 2006.

- ↑ Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, George W. Downs, (2005). "Development and Democracy".

Foreign Affairs, September/October 2005. Joseph T. Single, Michael M. Weinstein, Morton H. Halperin, (2004). "Why Democracies Excel". Foreign Affairs, September/October 2004. - ↑ Ross, Michael Lewin (2001). "Does Oil Hinder Democracy?". World Politics 53 (3): 325–361. doi:10.1353/wp.2001.0011.

- ↑ Doucouliagos, H., Ulubasoglu, M (2006). "Democracy and Economic Growth: A meta-analysis". School of Accounting, Economics and Finance Deakin University Australia.

- ↑ Amartya Sen, (1999). "Democracy as a Universal Value". Journal of Democracy, 10.3, 3–17. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ↑ Franco, Álvaro, Carlos Álvarez-Dardet and Maria Teresa Ruiz (2004). "Effect of democracy on health: ecological study (required)". British Medical Journal 329 (7480): 1421–1423. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7480.1421. PMC 535957. PMID 15604165.

- ↑ McKee, Marin and Ellen Nolte (2004). "Lessons from health during the transition from communism". British Medical Journal 329 (7480): 1428–1429. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7480.1428. PMC 535963. PMID 15604170.

- ↑ Hegre, Håvard, Tanja Ellington, Scott Gates, and Nils Petter Gleditsch (2001). "Towards A Democratic Civil Peace? Opportunity, Grievance, and Civil War 1816–1992". American Political Science Review 95: 33–48. Ray, James Lee (2003). A Lakatosian View of the Democratic Peace Research Program From Progress in International Relations Theory, edited by Colin and Miriam Fendius Elman (PDF). MIT Press.

- ↑ R. J. Rummel, Power Kills. 1997.

- ↑ Harff, Barbara (2003) No Lessons Learned from the Holocaust?.

Further reading

- Willard, Charles Arthur (1996). Liberalism and the Problem of Knowledge: A New Rhetoric for Modern Democracy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-89845-8, ISBN 0-226-89846-6. OCLC 33967621.

External links

| Look up liberal democracy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The Official Website of Democracy Foundation, Mumbai - INDIA

- British Democracy: Its Restoration and Extension

- Electoral reform - A vote of principle. The Guardian. 2010-07-03.