Lhasa (prefecture-level city)

| Lhasa 拉萨市 · ལྷ་ས་གྲོང་ཁྱེར། | |

|---|---|

| Prefecture-level city | |

|

Yangpachen Valley, Damxung County | |

.png) Location within China and Tibet | |

Relief map of Lhasa | |

| Coordinates: 29°39′N 91°07′E / 29.650°N 91.117°ECoordinates: 29°39′N 91°07′E / 29.650°N 91.117°E | |

| Country | China |

| Region | Tibet Autonomous Region |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 29,274 km2 (11,303 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 53 km2 (20 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 4,200 m (13,800 ft) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 559,423 |

| • Density | 19.1/km2 (49/sq mi) |

| Time zone | China Standard (UTC+8) |

| Area code(s) | 891 |

| Website |

www |

| Lhasa (prefecture-level city) | |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 拉萨市 | ||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 拉薩市 | ||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lāsà Shì | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||

| Tibetan | ལྷ་ས་གྲོང་ཁྱེར། | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Lhasa City,[lower-alpha 1] formerly Lhasa Prefecture, is a prefecture-level city, one of the main administrative divisions of the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. It covers an area of 29,274 square kilometres (11,303 sq mi) of rugged and sparsely populated terrain. The prefecture-level city contains Lhasa (formally Lhasa Chengguan District), the administrative capital of Tibet.

The prefecture-level city roughly corresponds to the basin of the Lhasa River, a major tributary of the Yarlung Tsangpo River. It lies on the Lhasa terrane, the last unit of crust to accrete to the Eurasian plate before the continent of India collided with Asia about 50 million years ago and pushed up the Himalayas. The terrane is high, contains a complex pattern of faults and is tectonically active. The temperature is generally warm in summer and rises above freezing on sunny days in winter. Most of the rain falls in summer. The upland areas and northern grasslands are used for grazing yaks, sheep and goats, while the river valleys support agriculture with crops such as barley, wheat and vegetables. Wildlife is not abundant, but includes the rare snow leopard and black-necked crane. Mining has caused some environmental problems.

The former prefecture is divided into seven mostly rural counties and one district, which contains the main urban area of Lhasa. The 2000 census gave a total population of 474,490, of whom 387,124 were ethnic Tibetans. The Han Chinese population was mainly concentrated in urban areas. The prefecture-level city is traversed by two major highways and by the Qinghai–Tibet Railway, which terminates in the city of Lhasa. Two large dams on the Lhasa River deliver hydroelectric power, as do many smaller dams and the Yangbajain Geothermal Station. The population is well-served by primary schools and basic medical facilities, although more advanced facilities are lacking. Tibetan Buddhism and monastic life have been dominant aspects of the local culture since the 7th century. Most of the monasteries were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, but since then many have been restored and serve as tourist attractions.

Geography

Location

Lhasa lies in south-central Tibet, to the north of the Himalayas. The prefecture-level city is 277 kilometres (172 mi) from east to west and 202 kilometres (126 mi) from north to south. It covers an area of 29,518 square kilometres (11,397 sq mi).[2] It is bordered by Nagqu Prefecture to the north, Nyingchi Prefecture to the east, Lhoka (Shannan) Prefecture to the south and Shigatse prefecture-level city to the west.[3] The prefecture-level city roughly corresponds to the basin of the Lhasa River, which is the center of Tibet politically, economically and culturally.[4] Chengguan District is also the center of Tibet in terms of transport, communications, education and religion, the most developed part of Tibet and a major tourist destination with sights such as the Potala Palace, Jokhang and Ramoche Temple.[5]

Lhasa River basin

.jpg)

Lhasa prefecture-level city roughly corresponds to the basin of the Lhasa River, a major tributary of the Yarlung Tsangpo River. Exceptions are the north of Damxung County, which crosses the watershed of the Nyenchen Tanglha Mountains and includes part of the Namtso lake,[6][lower-alpha 2] and Nyêmo County, which covers the basin of the Nimu Maqu River, a direct tributary of the Yarlung Tsangpo.[8] The river basin is separated from the Yarlung Tsangpo valley to the south by the Goikarla Rigyu range.[9] The largest tributary of the Lhasa River, the Reting Tsangpo, originates in the Chenthangula Mountains in Nagqu Prefecture at an elevation of about 5,500 metres (18,000 ft), and flows southwest into Lhasa past Reting Monastery.[10]

The Lhasa River drains an area of 32,471 square kilometres (12,537 sq mi), and is the largest tributary of the middle section of the Yarlung Tsangpo. The average altitude of the basin is around 4,500 metres (14,800 ft). The basin has complex geology and is tectonically active. Earthquakes are common.[4] Annual runoff is 10,550,000,000 cubic metres (3.73×1011 cu ft). Water quality is good, with little discharge of sewage and minimal chemical pesticides and fertilizers.[11]

The Lhasa River forms where three smaller rivers converge. These are the Phak Chu, the Phongdolha Chu which flows from Damxung County and the Reting Tsangpo, which rises beyond the Reting Monastery.[12] The highest tributary rises at around 5,290 metres (17,360 ft) on the southern slope of the Nyenchen Tanglha Mountains.[13] In its upper reaches the river flows southeast through a deep valley.[14] Lower down the river valley is flatter and changes its direction to the southwest, The river expands to a width of 150 to 200 metres (490 to 660 ft).[14] Major tributaries in the lower reaches include the Pengbo River and the Duilong River.[15] At its mouth the Lhasa Valley is about 3 miles (4.8 km) wide.[16]

The bulk of the water is supplied by the summer monsoon rains, which fall from July to September. There are floods in the summer from July to September, with about 17% of the annual runoff flowing in September. In winter the river has low water, and sometimes freezes. Total flow is about 4 cubic kilometres (0.96 cu mi), with average flow about 125 cubic metres per second (4,400 cu ft/s).[14] The total hydropower potential of the river basin is 2,560,000 kW.[11] Zhikong Hydro Power Station in Maizhokunggar County delivers 100 MW.[17] The Pangduo Hydro Power Station in Lhünzhub County has total installed capacity of 160 MW.[18]

Geology

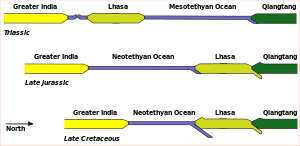

The former Lhasa prefecture lies in the Lhasa terrane, to which it gives its name. This is thought to be the last crustal block to accrete to the Eurasian plate before the collision with the Indian plate in the Cenozoic.[19] The terrane is separated from the Himalayas to the south by the Yarlung-Tsangpo suture, and from the Qiangtang terrane to the north by the Bangong-Nujiang suture.[20] The Lhasa terrane consisted of two blocks before the Mesozoic, the North Lhasa Block and the South Lhasa Block.[21] These blocks were joined in the Late Paleozoic.[19]

The Lhasa terrane moved northward and collided with the Qiangtang terrane along the Bangong suture.[22][23] The collision began towards the end of the late Jurassic (c. 163–145 Ma[lower-alpha 3]), and collision activity continued until the early Late Cretaceous (c. 100–66 Ma). During this period the terrane may have been shortened by at least 180 kilometres (110 mi).[20] The collision caused a peripheral foreland basin to form in the north part of the Lhasa terrane. In some parts of the foreland basin the north-dipping subduction of the Neotethyan oceanic crust below the Lhasa terrane caused volcanism. The Gangdese batholith was formed as this subduction continued along the southern margin of the Lhasa terrane.[24] The Gangdese intrudes the southern half of the Lhasa terrain.[25]

Contact with India began along the Yarlung-Zangbo suture around 50 Ma during the Eocene, and the two continents continue to converge. Magmatism continued in the Gangdese arc until as late as 40 Ma.[25] There was significant crustal shortening as the collision progressed.[26] The South Lhasa terrane experienced metamorphism and magmatism in the Early Cenozoic (55–45 Ma) and metamorphism in the Late Eocene (40–30 Ma), presumably due to the collision between the continents of India and Eurasia.[19]

Rocks in this region include sedimentary rocks from the Paleozoic and Mesozoic into which granite has intruded during the Cretaceous. The rocks have metamorphosed and are deeply eroded and faulted.[10] The rocks exposed in the Reting Tsangpo canyon range in age from 400 Ma to 50 Ma. The result of faulting has been to often juxtapose relatively recent rocks with much older rocks. Some parts of the ocean floor were pushed up onto the Tibetan Plateau and formed marble or slate. Sea fossils from 400 Ma are found in the river's canyons, and houses are roofed with slate.[10]

The Yangbajing Basin lies between the Nyainquentanglha Range to the northwest and the Yarlu-Zangbo suture to the south.[27] The Yangbajain Geothermal Field is in the central part of a half-graben fault-depression basin caused by the foremontane fault zone of the Nyainqentanglha Mountains.[28] The SE-dipping detachment fault began to form about 8 Ma.[29] The geothermal reservoir is basically a Quaternary basin underlaid by a large granite batholith. The basin has been filled with glacial deposits from the north and alluvial-pluvial sediments from the south. Fluid flows horizontally into the reservoir through the faults around the basin.[28] Chemical analysis of the thermal fluid indicate that there is shallow-seated magmatic activity not far below the geothermal field.[30]

During the ice ages of the last two million years the Tibetan plateau and the Himalayas have been covered by the expanded polar ice cap several times. As the ice moved it eroded the rock, filling the river canyons with gravel. In some sections the rivers have cut through the gravel and flow swiftly over bedrock, and in some areas large boulders have fallen into the rivers and formed rapids.[10]

Climate

The Lhasa valley is roughly the same latitude as the southern US, but at an altitude of 3,610 metres (11,840 ft) or more it is of course cooler.[31] The central river valleys of Tibet are warm in summer, and even in the coldest months of winter the temperature is above freezing on sunny days.[32] The climate is semi-arid monsoon, with a low average temperature of 1.2 to 7.5 °C (34.2 to 45.5 °F). Average annual precipitation is 466.3 millimetres (18.36 in), with 85% falling in the June–September period.[4] Typically there are 3,000 hours of sunshine each year.[2] It is cooler in the northern regions, warmer in the south. Annual figures:

| District | Region | Average temperature | Frost-free days | Precipitation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | °F | mm | in | |||

| Chengguan District[5] | Central | 8° | 46° | 110 | 500 | 20 |

| Dagzê County[33] | Central | 7.5° | 45.5° | 130 | 500 | 20 |

| Damxung County[34] | North | 1.3° | 34.3° | 62 | 481 | 18.9 |

| Doilungdêqên County[35][36] | Central | 7° | 45° | 120 | 310 | 12 |

| Lhünzhub County [37] | Central | 2.9–5.8° | 37.2–42.4° | 120 | 310 | 12 |

| Maizhokunggar County[38] | Central | 5.1–9.1° | 41.2–48.4° | 90 | 515.9 | 20.31 |

| Nyêmo County[39][8] | South | 6.7° | 44.1° | 100 | 324.2 | 12.76 |

| Qüxü County[40] | South | 150 | 441.9 | 17.40 | ||

Studies of temperature and precipitation data from 1979 to 2005 indicate that higher temperatures are leading to longer snow-free periods at the lower elevations. However, at higher levels the amount of precipitation has increased, so despite warming the snow-free period is shorter.[41]

Environment

Most of the population of Tibet lives in the southern valleys, including those around Lhasa.[42] The higher regions are used by nomadic drokpa who tend herds of yaks, sheep and goats on the steppe grasslands of the hills and high valleys.[42][31] In the lower parts it is possible to cultivate products that include barley, wheat, black peas, beans, mustard, hemp, potatoes, cabbage, cauliflower, onions, garlic, celery and tomatoes. The traditional staple food is barley flour called tsampa, often combined with buttered tea and made into a paste.[42]

A visitor described the valley around Lhasa in 1889 as follows,

The plain over which we are riding is a wonderfully fruitful one. It is skirted on the south by the Kyi[lower-alpha 4] river, and is watered, moreover, by another smaller stream from the north, which flows into the Kyi ... some five miles west of Lhasa. All this land is carefully irrigated by means of dikes and cross-channels from both rivers. Fields of buckwheat, barley, pea, rape, and lindseed lie in orderly series everywhere. The meadows near the water display the richest emerald-green pasturage. Groves of poplar and willow, in shapely clumps, combine with the grassy stretches to give in places a parklike appearance to the scene. Several hamlets and villages, such as Cheri, Daru, and Shing Dongkhar, are dotted over these lands. A fertile plain truly for a besieging army![43]

The Lhasa region does not have abundant wildlife or great numbers of species, but the Lhasa valley does support wintering populations of hundreds of black-necked cranes.[44] Hutoushan Reservoir lies in Qangka Township, Lhünzhub County. The reservoir is bordered by large swamps and wet meadows, and has abundant plants and shellfish.[45] The reservoir, which lies in the Pengbo valley, is the largest in Tibet, with total storage of 12,000,000 cubic metres (420,000,000 cu ft).[15] Endangered black-necked cranes migrate to the middle and southern part of Tibet every winter, and may be seen on the reservoir and elsewhere in the Lhasa region.[46] Other wildlife includes bharal, pheasants, roe deer, Thorold's deer, Mongolian gazelle, Siberian ibex, otter, brown bear, snow leopard and duck.[35][47][48][39] Medicinal plants include fritillaries (fritillaria), stonecrop (rhodiola), Indian barberry (berberis aristata), Chinese caterpillar fungus (ophiocordyceps sinensis), codonopsis and Lingzhi mushroom (ganoderma).[35][47][48][39]

The dams on the Lhasa river built as part of the Three Rivers Development Project are unlikely to affect the flow of the Brahmaputra in India.[49] However, the climate and soil are unsuitable for large-scale irrigation. Where grasslands have been converted into irrigated farms fed by dams the result may damage the environment.[50] Jama wetland in Maizhokunggar County is vulnerable to grazing and climate change.[51] Extensive mining in some mountainous regions have turned areas of what was green pasturage into a grey wasteland. The authorities are reported to have suppressed protests by the local people.[52] Military personnel have been involved in efforts to protect and improve the environment, including replanting programs.[53]

A 2015 study reported that during the non-monsoon season the levels of arsenic in the Duilong River, at 205.6 μg/L were higher than the WHO guideline of 10 μg/L for drinking water.[54] The source of the pollution seems to be untreated water from the Yangbajain Geothermal Field power station. It can be detected 90 kilometres (56 mi) downstream from this site.[55]

Administrative divisions

Lhasa prefecture-level city consists of one district and seven counties. Chengguan District contains most of the urban area of Lhasa, which lies in the Lhasa River valley floor.

| Name | Population (2010) | Area (km²) | Density (/km²) |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chengguan District | 279,074 | 525 | 531.56 | |

| Dagzê County | 26,708 | 1,361 | 19.62 | |

| Damxung County | 46,463 | 10,234 | 4.54 | |

| Doilungdêqên County | 52,249 | 2,672 | 19.55 | |

| Lhünzhub County | 50,246 | 4,100 | 12.25 | |

| Maizhokunggar County | 44,674 | 5,492 | 8.13 | |

| Nyêmo County | 28,149 | 3,266 | 8.61 | |

| Qüxü County | 31,860 | 1,624 | 19.61 |

Chengguan District

Chengguan District is located on the middle reaches of the Lhasa River, with land that rises to the north and south of the river. It is 28 kilometres (17 mi) from east to west and 31 kilometres (19 mi) from north to south. Chengguan District is bordered by Doilungdêqên County to the west, Dagzê County to the east and Lhünzhub County to the north. Gonggar County of Lhoka (Shannan) Prefecture lies to the south.[5] Chengguan District has an elevation of 3,650 metres (11,980 ft) and covers 525 square kilometres (203 sq mi). The urban built-up area covers 60 square kilometres (23 sq mi). The average annual temperature is 8 °C (46 °F). Annual precipitation is about 500 millimetres (20 in), mostly falling between July and September.[5]

Before the Chinese takeover the city of Lhasa had a population of 25,000–30,000, or 45,000–50,000 if the large monasteries around the city are included.[56] The old city formed a quadrangle about 3 square kilometres (1.2 sq mi) around the Jokhang temple, about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) to the east of the Potala Palace.[57] During the period before the reforms introduced by Deng Xiaoping the old city of Lhasa was left largely intact, while bleakly functional compounds containing symmetrical dormitory-type buildings for both living and working were built apart from the city along the main roads.[58]

By 1990 the city had expanded to cover 40 square kilometres (15 sq mi), with an official population of 160,000.[59] The 2000 official census gave a total population of 223,001, of which 171,719 lived in the areas administered by sub-districts and residential committees. 133,603 had urban registrations and 86,395 had rural registrations, based on their place of origin.[60] By 2013 the urban area filled most of the natural Lhasa River valley in Chengguan District.[61] A 2011 book estimated that up to two-thirds of the city's residents are non-Tibetan, although the government states that Chengguan District as a whole is still 63% ethnic Tibetan.[62]

Dagzê County

Dagzê County has a total area of 1,373 square kilometres (530 sq mi). It has an average elevation of 4,100 metres (13,500 ft) above sea level, and descends from higher ground in the north and south to 3,730 metres (12,240 ft) in the lowest part of the Lhasa river valley.[63] The average temperature is 7.5 °C (45.5 °F), with about 130 days free of frost. Average rainfall is 450 millimetres (18 in).[33] About 80%–90% of precipitation falls in the summer.[64]

As of 2013 the total population was 29,152.[63] The main occupation is agriculture. As of 2012 per capita income of farmers and herdsmen was 6,740 yuan.[63] In 2010 there were 28 schools in the county, including one junior high school and one kindergarten, with 276 full-time teachers. There is a county hospital and five township hospitals. The Sichuan-Tibet Highway (China National Highway 318) runs through the county.[33] The main monasteries in Dagzê are Ganden Monastery and Yerpa.[64]

Damxung County

Damxung County has an area of 10,036 square kilometres (3,875 sq mi), with rugged topography.[65] As of 2013 the population was 40,000, up from 35,000 in 1997.[6] It is tectonically active. On 6 October 2008 an earthquake measuring 6.6 on the Richter magnitude scale was reported.[34] In November 2010 a moderate quake in Damxung at 5.2 on the Richter scale shook office windows in Lhasa. There were no casualties, but houses were damaged.[66]

In the extreme northeast of the county, Namtso lake has an area of 1,920 square kilometres (740 sq mi), of which 45% lies in Damxung county. Namtso is one of the great lakes of the Tibetan plateau. The Nyenchen Tanglha (or Nyainqentanglha) mountains extend along the northwest of the county. Mount Nyenchen Tanglha is the highest peak in the region, at 7,111 metres (23,330 ft). The Nyainqêntanglha mountains define the watershed between northern and southern Tibet.[6] A valley with elevation of about 4,200 metres (13,800 ft) runs parallel to the mountains to their southeast, sloping from northwest to southeast. 30% of the county's total area is in the prairie of this valley.[34]

Damxung is cold and dry in the winter, cool and wet in summer, with very variable weather. The average annual temperature is 1.3 °C (34.3 °F), with only 62 frost-free days. The land is frozen from the start of November to the following March. Pasture has 90–120 days for growth. Average annual precipitation is 481 millimetres (18.9 in).[34] Natural grasslands cover 693,171 hectares (1,712,860 acres), of which 68% is considered excellent.[65] Almost all the people are engaged in rearing livestock, including yaks, sheep, goats and horses.[34]

The Qinghai-Tibet Highway (China National Highway 109) runs from east to west across the county. Damxung Railway Station links the county to the city of Lhasa to the south.[6] There is a large geothermal field at Yangbajain harnessed by generating units that deliver 25,181 kilowatts to the city of Lhasa to the south.[67] The transmission line follows the Duilong River south through Doilungdêqên County.[68] Kangma Monastery is 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) from the county seat. The meditation room has 1,213 carved stone reliefs of Buddha that are about three hundred years old.[69] Yangpachen Monastery in Yangbajain is historically the seat of the Shamarpas of Karma Kagyu.[70] The monastery was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, but later was rebuilt.[71]

Doilungdêqên County

Doilungdêqên County contains the western suburbs of the city of Lhasa, which begin about 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) from the city center. It covers an area of 2,704 square kilometers, with 94,969 acres of farmland.[35] The county borders on the north Tibet grasslands in the northwest. The valley of the Duilong River leads south to the Lhasa River. The Duilong is 95 kilometres (59 mi) in length. In the south the county occupies part of the south bank of the Lhasa River.[36] The county has an average elevation of 4,000 metres (13,000 ft), with a highest elevation of 5,500 metres (18,000 ft) and a lowest point at 3,640 metres (11,940 ft).[35]

There are about 120 frost-free days annually.[35] Annual mean temperature is 7 °C (45 °F), with temperatures in January falling below −10 °C (14 °F) Annual precipitation is about 440 millimetres (17 in), with autumn rainfall of 310 millimetres (12 in). The county is agriculturally rich and was used by the Tibetan kings as a source of food for Lhasa.[36]

The seat of government is in the town of Donggar.[35] This is just 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) from downtown Lhasa.[36] In 1992 there were 33,581 people in 6,500 households, with 94.28% of the people engaged in farming. About 90% of the people were ethnic Tibetan, with most people of other ethnicity living in Donggar.[36] The main mineral resources are coal, iron, clay, lead and zinc.[35] Tsurphu Monastery, built in 1189, is treated as a regional cultural relic reserve.[72] The Nechung Monastery, former home of the Nechung Oracle, is located in Naiquong township.[73] Nechung was built by the 5th Dalai Lama (1617–82).[74]

Lhünzhub County

Lhünzhub County is located around 65 km (40 mi) northeast of metropolitan Lhasa. It includes the Pengbo River Valley and the upper reaches of the Lhasa River. It covers an area of 4,512 km2 (1,742 sq mi).[48] The county is geologically complex, with an average elevation of 4,000 metres (13,000 ft).[48] The administrative center is the town of Lhünzhub.[75]

As of 2000 the county had a total population of 50,895, of which 8,111 lived in a community designated as urban. 2,254 had non-agricultural registration and 48,362 had agricultural registration.[60] In the south the Pengbo valley has an average elevation of 3,680 metres (12,070 ft) with a mild climate. The average temperature is 5.8 °C (42.4 °F).[48] The northern "three rivers" section, crossed by the Lhasa River and its tributary the Razheng River, is mountainous and has an average elevation of 4,200 metres (13,800 ft). It has average annual temperature of 2.9 °C (37.2 °F) and is mostly pastoral, with yak, sheep and goats.[48]

The Pengbo valley is the main grain-producing region of Lhasa prefecture-level city and Tibet, with a total of 11,931 hectares (29,480 acres) of arable land.[37] Crops include barley, winter wheat, spring wheat, canola and vegetables such as potato.[76] Livestock includes yak, sheep, goats and horses.[48] In 2010 the per capita income of farmers and herdsmen was 4,587 yuan.[lower-alpha 5] The Pengbo valley has a long history of pottery-making. Products include braziers, flower pots, vases, jugs and so on.[37] Mining is an important source of income. In 2011 the government has plans to more actively promote tourism.[78] The Pangduo Hydro Power Station became operational in 2014.[18] It has been called the "Tibetan Three Gorges".[79]

The county is a center of Tibetan Buddhism. There were thirty-seven gompas including twenty-five lamaseries with 919 monks and twelve nunneries with 844 nuns as of 2011.[37] Reting Monastery was built in 1056 by Dromtön (1005–1064), a student of Atiśa. It was the earliest monastery of the Gedain sect, and the patriarchal seat of that sect.[80]

Maizhokunggar County

Maizhokunggar County is located on the middle and upper sections of the Lhasa River and the west of Mila Mountain.[81] Mila (or Mira) Mountain, at 5,018 metres (16,463 ft), forms the watershed between the Lhasa River and the Nyang River.[82][83] The Gyama Zhungchu, which runs through Gyama Township, is a tributary of the Lhasa River.[84] Maizhokunggar County is about 68 kilometres (42 mi) east of Lhasa, has an area of 5,492 square kilometres (2,120 sq mi) with an average elevation of more than 4,000 metres (13,000 ft).[85] The annual average temperature is 5.1 to 9.1 °C (41.2 to 48.4 °F). There are about 90 frost-free days each year. Annual rainfall is 515.9 millimetres (20.31 in).[38] China National Highway 318 runs through the county from east to west.[85] The 100 MW Zhikong Hydro Power Station on the Lhasa River came into operation in September 2007.[17]

The total population as of 2010 was 48,561 people in 9,719 households, the great majority engaged in farming and herding.[85] 98% of the population are ethnic Tibetan.[86] The seat of government is in Kunggar in the west of the county.[38] Many of the people depend on farming or herding. Development efforts include increased farm animal husbandry, feedstock production, greenhouses for vegetables, and breeding programs.[87] Crops include barley, winter wheat, spring wheat, canola, peas, cabbage, carrots, eggplant, cucumbers, lettuce, spinach, green peppers, pumpkins, potatoes and other greenhouse crops.[86] The economy is driven by mineral extraction, which was expected to account for 73.85% of total tax revenue in 2007 while employing 419 people.[87]

Traditional folk handicrafts include pottery, willow basketwork, wooden objects, mats and gold and silver items.[86] The county is especially noted for its pottery, which does not corrode, retains heat and has an ethnic style. It has an over 1000-year-old history.[88] The Drikhung Thil Monastery of the Kagyu Sect was founded in 1179 by Lingchen Repa, a disciple of Phagmo Drupa. The monastery is the home of the Drikhung Kagyu School of the Kagyu sect.[89] The ruined Gyama Palace, in the Gyama Gully in the south of the county, was built by Namri Songtsen in the 6th century after he had gained control of the area from Supi.[90]

Nyêmo County

Nyêmo County is located in the middle section of the Brahmaputra, 140 kilometres (87 mi) from Lhasa. It is mainly agricultural and pastoral, with an area of 3,276 square kilometres (1,265 sq mi) and an average elevation of 4,000 metres (13,000 ft).[39] The Nimu Maqu River flows through the county from north to south. The Yarlung Tsangpo River forms its southern boundary.[8] The highest point is a peak at 7,048.8 metres (23,126 ft) above sea level, and the lowest point is where the Maqu River empties into the Brahmaputra at an elevation of 3,701 metres (12,142 ft).[91] The county has a temperate semi-arid plateau monsoon climate, with about 100 frost-free days. Annual rainfall is 324.2 millimetres (12.76 in).[39]

Nyêmo County has its headquarters in Nyêmo Town.[39] The county seat is 3,809 metres (12,497 ft) above sea level.[39] As of 2011 the total population was 30,844 people, of whom 28,474 were engaged in agriculture or herding.[39] By 2012 the per capita income of farmers and herdsmen had reached 6,881 yuan.[92] In the 7th century Nyêmo was producing printing materials, clay-based incense and wooden-sole shoes.[93] Nyêmo's long tradition of making paper and printing texts using woodblocks dates back to this period. Nyêmo County has China's first museum of Tibetan text.[94] There are 22 temples. As of 2011 there were 118 monks and 99 nuns.[39] The Nyêmo Chekar monastery is known for its 16th century murals depicting reincarnations of the Samding Dorje Phagmo.[95]

Qüxü County

Qüxü County has a total area of 1,680 square kilometres (650 sq mi), with an average elevation of 3,650 metres (11,980 ft).[96] The county is in the Yarlung Tsangpo valley, and is mostly relatively flat, but rises to the Nyainqêntanglha Mountains in the north. The Lhasa River runs south through the eastern part of the county to its confluence with the Yarlung Tsangpo River, which forms the southern boundary of the county. The lowest elevation is 3,500 metres (11,500 ft), and the highest summit elevation is 5,894 metres (19,337 ft).[40] Qüxü County has about 150 days a year without frost. Annual precipitation is 441.9 millimeters (17.40 in).[40]

Qüxü County has its headquarters in Qüxü Town.[40] The fifth census in 2000 recorded a population of 29,690.[40] The county seat has been growing fast, and had 5,000 people by 2002.[96] China National Highway 318 runs through Qüxü County from Lhasa towards the west. Bridges span the Lhasa River and the Yarlung Tsangpo River.[47]

Qüxü County is semi-agricultural and crops grown are mainly highland barley, winter wheat, spring wheat, peas and rapeseed. Apples and walnuts are also produced. Animal husbandry is also strong, with the main animals farmed including yak, cattle, goats, sheep, horses, donkeys, pigs, and chickens.[47] As of 2002 the per capita net income of farmers and herdsmen was 1,960 yuan.[96] The Nyethang Drolma Lhakhang Temple is located in Qüxü County, said to have been founded in 1055 by Dromtön, a pupil of Atiśa.[97]

Demographics

The demographics of Lhasa prefecture-level city are difficult to define precisely due to the way in which administrative boundaries have been drawn, and the way in which statistics are collected. The population of Lhasa prefectural-level city is about 500,000, of whom about 80% are ethnic Tibetan and most of the others are ethnic Han Chinese. Perhaps 250,000 people live in the city and in towns, most of them in or near Chengguan District, and the remainder live in rural areas.

Ethnicity

The 2000 census give the following breakdown for the population of the prefecture-level city as a whole:[98]

| Total Population | Han Population | Tibetan Population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subdistricts (jiedao) | 171,719 | 62,226 | 104,203 |

| Towns (zhen) | 60,117 | 3,083 | 56,614 |

| Townships (xiang) | 242,663 | 15,275 | 226,307 |

| Total | 474,499 | 80,584 | 387,124 |

The 2000 census counts more than 105,000 people in Chengguan District who are registered elsewhere. Most of them are Han, with agricultural registrations.[60] Outside Chengguan District, in 2000 the rural townships almost all had Han populations below 2.85%, other than one in Duilongdeqing County and one in Qushui County, both near the metropolitan district of Lhasa. Urban towns other than Yangbajain had Han populations of between 2.86% and 11.25%. Within the metropolitan district Han population ranged from 11.26% to 11.25% in the southern rural township to 46.56% to 47.46% in the city street offices.[99] Han migrants accounted for 20% of the population, but held a much higher percentage of the higher-status office and service-sector jobs. Hans also dominated construction, mining and trade.[100]

According to the November 2000 census, the ethnic distribution in Lhasa Prefecture-level City was as follows:[101]

| Major ethnic groups in Lhasa Prefecture-level City by district or county, 2000 census | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Tibetans | Han Chinese | others | ||||

| Chengguan District | 223,001 | 140,387 | 63.0% | 76,581 | 34.3% | 6,033 | 2.7% |

| Dagzê County | 24,906 | 24,662 | 99.0% | 212 | 0.9% | 32 | 0.1% |

| Damxung County | 39,169 | 38,689 | 98.8% | 347 | 0.9% | 133 | 0.3% |

| Doilungdêqên County | 40,543 | 38,455 | 94.8% | 1,868 | 4.6% | 220 | 0.5% |

| Lhünzhub County | 50,895 | 50,335 | 98.9% | 419 | 0.8% | 141 | 0.3% |

| Maizhokunggar County | 38,920 | 38,567 | 99.1% | 220 | 0.6% | 133 | 0.3% |

| Nyêmo County | 27,375 | 27,138 | 99.1% | 191 | 0.7% | 46 | 0.2% |

| Qüxü County | 29,690 | 28,891 | 97.3% | 746 | 2.5% | 53 | 0.2% |

| Total | 474,499 | 387,124 | 81.6% | 80,584 | 17.0% | 6,791 | 1.4% |

Administrative divisions

Lhasa metropolitan district includes most of the built-up area, which counts as urban, and four rural townships. The counties also contain urban towns, of which there are nine in the prefectural municipality.[60]

Official census figures for 2000 are:[60]

| Total Population | City/Town Population | Non-Agricultural Registration | Agricultural Registration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chengguan District | 223,001 | 171,719 | 133,603 | 86,395 |

| Dagzê County | 24,906 | 7,382 | 1,464 | 23,431 |

| Damxung County | 39,169 | 8,530 | 2,023 | 36,975 |

| Doilungdêqên County | 40,543 | 17,197 | 3,836 | 36,608 |

| Lhünzhub County | 50,895 | 8,111 | 2,254 | 48,362 |

| Maizhokunggar County | 38,920 | 5,409 | 1,526 | 37,384 |

| Nyêmo County | 27,375 | 6,082 | 1,190 | 25,981 |

| Qüxü County | 29,690 | 7,406 | 1,564 | 28,057 |

| Municipality total | 474,499 | 231,836 | 147,460 | 323,193 |

The census figures differ considerably from the Tibet Statistical Yearbooks for the same period, since the yearbook only includes the registered population and counts them based on place of origin rather than place of residence. The 1990 census used an approach similar to the yearbook, so the numbers are misleading, but the 2000 census tried to count people who had actually been present in Lhasa for over six months. The census distinguishes between "agricultural" and "non-agricultural" registration, but this does not reflect the actual occupations of the people. Many with an "agricultural" registration may in fact work in the city or in a town. Also, the census was taken in November, when many of the ethnic Han workers in seasonal industries such as construction would have been away from Tibet. Finally, the census does not count the military.[60]

Infrastructure

Highways

China National Highway 318 enters the prefecture-level city from the east at Mila Mountain, where it reaches an elevation of 5,000 metres (16,404 ft).[102] The highway runs through Maizhokunggar County from east to west.[85] It continues along the south bank of the Lhasa River through Dagzê County, then crosses to the north of the river in Chengguan District and runs through the center of the urban district. It turns south to cross Doilungdêqên County, where it is joined by 109, and continues down the west side of the Lhasa River through Qüxü County, and then along the north shore of the Yarlung Tsangpo through Nyêmo County, and onward to the west.[103]

.jpg)

China National Highway 109 (the Qinghai–Tibet Highway) runs through Damxung County from the northeast to southwest, then turns to the southeast at Yangbajain.[103] It then runs through Doilungdêqên County along the Duilong River valley, to join China National Highway 318 just west of Lhasa.[104] The Lhasa Airport Expressway from Lhasa to Lhasa Gonggar Airport in Lhoka (Shannan) Prefecture is the first expressway in the Tibet Autonomous Region.[105] Construction began in April, 2009. The expressway is 37.8 kilometres (23.5 mi) long and has four lanes.[106]

Railroad

The Qinghai–Tibet Railway runs through the Lhasa prefecture-level city beside the Qinghai–Tibet Highway through Damxung and Doilungdêqên Counties.[104] It terminates at Lhasa Railway Station in Niu New Area (Liuwu Township).[107] The terminus of the Qinghai–Tibet line, this station is over 3,600 metres (11,800 ft) above sea level, and is its largest passenger transport station. It includes a clinic with oxygen treatment facilities. The station uses solar energy for heating.[108] The Liuwu Bridge links central Lhasa to Lhasa Railway Station and the newly developed Niu New Area of Doilungdêqên County on the south bank of the Lhasa River. Residents in the area were resettled to make way for the new development.[109]

Power

The Yangbajain Geothermal Station was established in 1977 to exploit the Yangbajain Geothermal Field in Damxung.[110] It is the first geothermal power station to be built in Tibet and is the largest geothermal steam power plant in China.[111] 4,000 kW of electricity from Yangbajain began to be delivered to Lhasa in 1981 along a transmission line that followed the Doilung Qu River.[68] It was the main power supply for Lhasa until the Yamdrok Hydropower Station came into operation.[111] By the end of 2000 eight steam turbo generators had been installed at the Yangbajain Geothermal Station, each with capacity of 3,000 kW, giving a total of 25,000 kW.[111] The geothermal field delivers 25,181 kilowatts, or 100 million kilowatts annually, to the city of Lhasa to the south.[67]

The Pangduo Hydro Power Station has been called "Tibet's Three Gorges Dam". It impounds the Lhasa River in Pondo Township of Lhünzhub County, about 63 kilometres (39 mi) from Lhasa.[112] It is at an elevation of 13,390 feet (4,080 m) above sea level, upstream from the 100MW Zhikong Dam at 12,660 feet (3,860 m).[113] The rock-fill dam impounds 1,170,000,000 cubic metres (4.1×1010 cu ft) of water.[114] The power station has total installed capacity of 160 MW.[18]

The Zhikong Hydro Power Station lies between the middle and lower reaches of the Lhasa River, also called the Kyi River.[17] It is about 100 kilometres (62 mi) northeast of Lhasa, in Maizhokunggar County.[115][116] It is at an elevation of 12,660 feet (3,860 m) above sea level, downstream from the Pangduo Hydro Power Station.[113] The Zhikong Dam, a rock-fill dam, is 50 metres (160 ft) tall.[117] It impounds 225,000,000 cubic metres (7.9×109 cu ft) of water.[17] Installed capacity is 100 MW.[116]

Other facilities

The rural counties generally have numerous primary schools at the village level, with high levels of attendance, and at least one secondary school. In 2010 there were 28 schools in Dagzê County, including one junior high school and one kindergarten.[33] As of 2009 there were 37 primary and secondary school buildings in Damxung County.[6] Maizhokunggar County has one high school, 14 full primary schools and 74 village schools.[86] Nyêmo County has 24 primary and secondary schools, including one junior high school.[39] As of 2002 Qüxü County had one County Middle School, and 18 primary schools.[96] Outside Lhasa most of the Tibetans do not understand the Chinese language, so Tibetan is the natural language for basic instruction. However, this may be affected by the availability of teachers and the preference of the local administration.[118] As of 2003 the former bilingual mode of instruction had been changed to giving instruction in Chinese in some of the counties near Lhasa. Examination results were already poor in subjects such as mathematics and physics. Marks dropped further after the change.[119]

Some of the township seats have a small clinic. Most have only a health station, usually poorly supplied.[120] There is a county hospital and five township hospitals in Dagzê County.[33] There were seven hospitals in Damxung in 2009, including a county hospital, with a total of 40 beds.[121] The first drug rehabilitation center in Tibet was being constructed in Duilongdeqing County in 2009. It would provide physiological rehabilitation, psychological therapy and job training for up to 150 drug addicts.[122] Lhünzhub County has 23 health care establishments, including a County People's Hospital with 30 beds.[37] Maizhokunggar has been selected as a Cooperative Medical System experimental site, which has resulted in a very high percentage of people with health care coverage.[123] Nyêmo County has a county hospital with 42 medical staff, eight rural health centers and 26 village clinics.[39]

The local television stations are Xizang TV (XZTV) and Lhasa Broadcasting and Television Center.[124] Lhünzhub County has a local radio and television station. TV coverage is received by 72.1% of the population, and radio by 83.4% of the population.[37] In Maizhokunggar County television is available to 36% of the population and radio to 48%.[86] There is a county television station in Nyêmo County.[39] As of 2002 in Qüxü County 98% of the population received radio coverage and 94% received television.[96] In 2015 there were 359,000 fixed line telephone subscribers in the whole of Tibet. The rugged high-altitude terrain makes it expensive to provide telecommunications services. The first mobile phone service was launched in 1993 with just one base station in Lhasa, and as late as 2005 mobile phones were expensive status symbols. Since then both mobile phones and internet usage have grown fast.[125]

As of 1996 the sole prison (jianyu) for judicially-sentenced political prisoners in Tibet was TAR Prison No. 1, also called Drapchi Prison after the neighborhood in Lhasa where it stands. It is for men serving sentences of five or more years. There is a labor camp (laogai) in Lhasa for men serving shorter sentences.[1] There are various other institutions where prisoners from Lhasa shi are held while they are being investigated, or where they undergo reform-through-labor.[126]

Temples and monasteries

Buddhism was adopted as the official religion of Tibet by king Songtsän Gampo (died 649) at a time when the rise of Hinduism was sweeping away Buddhism in India, the land of its birth. Over the next two centuries Buddhism became established in Tibet, now the center of the religion.[127] Tibetan Buddhism would become a pervasive influence on the lives of the people.[56] The first monastery, Samyé, was founded by Trisong Detsen (c. 740-798). Its buildings were arranged in a mandala pattern after the Odantapuri monastery in Bihar. The three-story monastery was completed in 766 and consecrated in 767. Seven Tibetans took monastic vows in a ceremony that marked the start of the long Tibetan tradition of monastic Buddhism.[128][lower-alpha 6]

Early foundations

Yerpa, on a hillside in Dagze County, is known for its meditation cave connected with Songtsän Gampo.[130] The cliffs contain some of the earliest known meditation sites in Tibet, some dating back to pre-Buddhist times. There are a number of small temples, shrines and hermitages. Songtsän Gampo's queen, Monza Triucham, founded the Dra Yerpa temple here.[131] Jokhang in Chengguan District is the most sacred temple in Tibet, built in the 7th century when Songtsän Gampo transferred his capital to Lhasa. It was designed to house an image of Buddha that the Nepalese queen Tritsun had brought. Later rulers and Dalai Lamas enlarged and elaborated the temple.[132]

Ramoche Temple to the north of Jokhang is considered the most important temple in Lhasa after Jokhang, and was completed about the same time.[133] Muru Nyingba Monastery is a small monastery located between the larger Jokhang temple and Barkhor in the city of Lhasa. It was the Lhasa seat of the former State Oracle who had his main residence at Nechung Monastery.[134] It was destroyed during the persecution of Buddhism under Langdarma (c. 838–841) but rebuilt by Atiśa (980–1054). The monastery was part of the Sakya sect at one time. but became Gelug under Sonam Gyatso, the 3rd Dalai Lama (1543–89).[135]

Middle period

The Nyethang Drolma Temple is southwest of Lhasa, 36 kilometres (22 mi) from the county seat and 33 kilometres (21 mi) from Lhasa.[136] It is in Nyétang, Qüxü County.[137] Some sources say that Atiśa (980–1054) built the monastery, which was expanded after his death by his pupil Dromtön (1004–64).[137] Another version says that Dromtön raised funds to build the temple to commemorate his old friend.[136] Dromtön built Reting Monastery in Lhünzhub County in 1056. It was the earliest monastery of the Gedain sect, and the patriarchal seat of that sect.[80] In 1240 a Mongol force sacked Reting monastery and killed 500 people. The gompa was rebuilt.[31] When the Gedain sect joined the Gelug sect in the 16th century the monastery adopted the reincarnation system.[80]

Tsurphu Monastery in Doilungdêqên County was built in 1189 and is treated as a regional cultural relic reserve.[72] The monastery was founded by Düsum Khyenpa, 1st Karmapa Lama, founder of Karma Kagyu school. It is the main Kagyu temple.[138] The Drigung Monastery of the Kagyu Sect was founded in 1179 in Maizhokunggar County. It is the home of the Drikhung Kagyu School of the Kagyu sect.[89] At one time Drigung was highly influential in both the political and religious spheres. It was destroyed in 1290 by Mongols led by a general from the rival Sakya sect, and although rebuilt was never able to regain its power.[139]

Yangpachen Monastery in Yangbajain, Damxung County was historically the seat of the Shamarpas of Karma Kagyu.[70] It is the main monastery of the Red Hat school of the Karma Kagyu sect. It was built in 1490, and through extensive repairs and additions grew into a major architectural complex that contained a large collection of cultural relics. The Red Hat school of Karma Kagyu died out in 1791.[71] Other monasteries founded outside the Gelug tradition include Taklung Monastery of the Kagyu school, founded in 1180 in Lhünzhub County,[140] and Nyêmo Chekar monastery of the Bodongpa school, founded in the 16th century in Nyêmo County.[141]

Gelug foundations

Ganden Monastery was built after 1409 at the initiative of Je Tsongkhapa, founder of the Gelug sect, and is the most important of this sect. It is 57 kilometres (35 mi) from Lhasa on the slopes of Wangbori Mountain at an elevation of 3,800 metres (12,500 ft), on the south bank of the Lhasa River in Dagze County. The mountain is said to have the shape of a reclining elephant. The monastery includes Buddha halls, palace residences, Buddhist colleges and other buildings.[142]

Drepung Monastery in Chengguan District was founded in 1416 by Jamyang Choge Tashi Palden (1397–1449), one of Tsongkhapa's main disciples. It was named after the sacred abode in South India of Shridhanyakataka.[143] At one time Drepung Monastery, with up to 10,000 resident monks, was the largest in the world. Sera Monastery was not much smaller.[144] Sera Monastery, about 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Lhasa, was founded in 1419 by Jamchen Chöjé Shakya Yeshé (1354-1435), a close disciple of Tsongkhapa.[145] Ganden, Drepung and Sera are called the great "Three Seats of Learning" of the Gulugpa school.[146]

The Nechung Monastery, former home of the Nechung Oracle, is located in Naiquong township, also in Duilongdeqing County .[73] Nechung was built by the 5th Dalai Lama (1617–82).[74] Other Gelug foundations include Sanga Monastery (1419, Dagzê County), Ani Tsankhung Nunnery (15th century, Chengguan District), Kundeling Monastery (1663, Chengguan District), *Nechung (17th century, Doilungdêqên County) and Tsomon Ling (17th century, Chengguan District).

Revolution and reconstruction

Most of the monasteries in the prefecture-level city suffered damage, and many were destroyed, before and during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). Jokhang was used as a military barracks and a slaughterhouse during the Cultural Revolution, and then as a hotel for Chinese officials.[132] Many of the statues were taken, or were damaged or destroyed, so most of the present statues are recent copies. Jokhang was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000.[147] Ramoche Temple was badly damaged during the Cultural Revolution but has been restored with assistance from the Swiss.[148] The Nyethang Drolma Temple survived the Cultural Revolution without much damage, and was able to preserve most of its valuable artifacts, due to the intervention of Premier Zhou Enlai at the request of the government of what is now Bangladesh.[149]

Reting Monastery was devastated by the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution, and has only been partially restored.[150] Tsurphu monastery was reduced to rubble, but the huge temples and chanting halls have been rebuilt.[151] Before and during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) Drigung Monastery was looted of almost all its collection of statues, stupas, thangkas, manuscripts and other objects apart from a few small statues that the monks managed to hide. The buildings were severely damaged. Reconstruction began in 1983 and seven of the fifteen temples were rebuilt.[152] Yangpachen Monastery was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, but later was rebuilt.[71]

Ganden Monastery was completely destroyed during the rebellion of 1959. In 1966 it was severely shelled by Red Guard artillery, and monks had to dismantle the remains.[153] The buildings were reduced to rubble using dynamite during the Cultural Revolution.[154] Re-building has continued since the 1980s.[155] Nechung was almost completely destroyed but has been largely restored. There is a huge new statue of Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava) on the second floor.[156]

Nine sites in the Lhasa valley were listed in 1985 by the TAR Cultural Relics Authority as "regionally protected buildings". These were Tsangkung Nunnery, Meru Monastery and Great Kashmiri Mosque in the old city, and the Karmashar Temple, Meru Nyingba Monastery and Northern, Southern, Eastern and Western Rigsum Temples elsewhere in the former prefecture.[157]

References

- ↑ The term Lasa Shi (拉萨市) literally means "Lhasa city" or "Lhasa municipality". It is at the same level as a prefecture for administrative purposes. It contains the urban area of Lhasa, the administrative center, but mainly consists of remote rural areas. There is no precise Chinese term for the urban area. The Chinese often refer to it as chengguanqu but officially Chengguan District, or Urban District, includes rural farming areas in addition to the city.[1]

- ↑ Namtso lake is the second-largest salt lake in China. It has vivid turquoise-blue waters and is set in spectacular scenery. The Tashi Dor Monastery is at an elevation of 4,718 metres (15,479 ft) in the southeastern corner of the lake.[7]

- ↑ Ma – Million years ago

- ↑ The Kyi River is another name for the Lhasa River

- ↑ A per capita income of 4,587 yuan converts to US$688 at an exchange rate of 0.15 dollars per yuan.[77]

- ↑ Multi-storey buildings such as monasteries in the earthquake-prone Lhasa region usually have battered walls, massive at the base and lighter higher up, with flexible timber frames. Preferably adobe brick is used for the upper floors. The roofs are flat, waterproofed with pounded limestone, and provide living space.[129]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Barnett 1996, p. 82.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lhasa, Baidu Baike.

- ↑ Tibet Maps, ChinaTourGuide.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Shen 1995, p. 151.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Chengguan District of Lhasa, Baidu Baike.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Damxung, Baidu Baike.

- ↑ Chow, Eimer & Heller 2009, p. 928.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Nyêmo County, Baidu Baike.

- ↑ Tibet, chinamaps.org.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Winn 2015.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Shen 1995, p. 152.

- ↑ McCue 2010, p. 125.

- ↑ Ortlam 1991, pp. 385–399.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Джичу, Географическая энциклопедия.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Shen 1995, p. 153.

- ↑ Waddell 1905, p. 317.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Zheng 2007.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Guan 2013.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Zhang et al. 2014, p. 170–171.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ozacar 2015.

- ↑ Wan 2010, p. 139.

- ↑ Wan 2010, p. 210.

- ↑ Metcalfe 1994, pp. 97–111.

- ↑ Leier et al. 2007, p. 363.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Alsdorf, BrownNelson & Makovsky 1998, p. 502.

- ↑ Liebke et al. 2010, p. 1199.

- ↑ Dor & Zhao 2000, p. 1084.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Shen 1996, p. 50.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, p. 214.

- ↑ Shen 1996, p. 17.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 McCue 2010, p. 126.

- ↑ Kapstein 2013, p. 7.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 Basic Dazi , DIIB.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 Mei 2008.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 35.6 35.7 Lhasa Duilongdeqing County Profile.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Ge Le & Li Tao 1996, p. 35.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 37.5 Linzhou, TibetOL.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Mozhugongka County, TibetOL.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 39.7 39.8 39.9 39.10 39.11 Nyêmo County Overview, Lhasa Municipality.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 Lhasa Qushui Introduction, CGN.

- ↑ J. Gao 2013, p. 594.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Powers 2007, p. 138.

- ↑ Sandberg 1889, p. 707.

- ↑ Bisht 2008, p. 73.

- ↑ Lhasa, Tibet Linzhou Hutoushan reservoir is a paradise....

- ↑ Lin 2013.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 Lhasa Qushui Introduction, Lhasa Tourism.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 48.5 48.6 Linzhou County Profile, LSIIB.

- ↑ Chellaney 2013, p. 158.

- ↑ Chellaney 2013, p. 160.

- ↑ Bai, Shang & Zhang 2012, p. 1761.

- ↑ Tibetans rebuked for protesting ... 2012.

- ↑ Guo 2014.

- ↑ Li 2013, p. 4143.

- ↑ Zhang & Huang 1997.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Powers 2007, p. 139.

- ↑ Pommaret 2003, p. 212.

- ↑ Pommaret 2003, p. 213.

- ↑ Pommaret 2003, p. 217.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 60.5 Yeh & Henderson 2008, pp. 21–25.

- ↑ Alexander 2013, p. 368.

- ↑ Johnson 2011, p. 81.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Dazi Overview, Dazi county.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Dazi, Baidu Baike.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Damxung Land Resources.

- ↑ Moderate quake jolts Tibet, Hindustan Times.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Damxung Mineral Resources.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Zhang & Tong 1982, p. 320.

- ↑ Lobsang & Zhang 2003.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Dowman 1988, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 Yangpachen Monastery, Meiya Travel.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Lin 2014.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Foster, Lee & Lin-Liu 2012, p. 787.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 LaRocca 2006, p. 28.

- ↑ Linzhou, Baidu.

- ↑ Linzhou Industry News, LSIIB.

- ↑ XE Currency Table: CNY - Chinese Yuan Renminbi.

- ↑ Government Work Report 2011.

- ↑ Qin 2013.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 Ling 2005, p. 73.

- ↑ Sanpower Group donated RMB300,000 to Mozhugongka.

- ↑ Niyang River, Tibet Vista.

- ↑ Mozhugongka County, Mozhugongka.

- ↑ Brown 2013.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 85.3 Mozhugongka County Overview, Lhasa Municipal.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 86.3 86.4 Mozhugongka County, China Intercontinental.

- ↑ Ceramic skill, treasure of herdsmen.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Ling 2005, p. 75.

- ↑ An 2003, p. 66.

- ↑ Nyêmo County, haotui.

- ↑ Nyêmo County 2012 Summary....

- ↑ Shakabpa 2009, p. 78.

- ↑ Inside Nimu, China Tibet Online.

- ↑ Diemberger 2014, p. 27.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 96.2 96.3 96.4 Booming Lhasa Qushui, CCTV.

- ↑ Qushui & Duilongdeqing County.

- ↑ Yeh & Henderson 2008, p. 25.

- ↑ Yeh & Henderson 2008, p. 26.

- ↑ Yeh & Henderson 2008, p. 26–27.

- ↑ Tabulation on Nationalities of 2000....

- ↑ A journey in Tibet: Mila Mountain.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Lhasa region map, China Mike.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Duilongdeqing County, Administrative divisions.

- ↑ 430 million yuan in place for Lhasa-Gongkar ... 2010.

- ↑ Shi 2011.

- ↑ Lhasa Railway Station, Tripadvisor.

- ↑ Lhasa Railway Station Duilongdeqing County.

- ↑ Resettlement and railroad construction in Lhasa.

- ↑ Yangbajing, Ministry of Culture.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 111.2 An 2003, p. 27.

- ↑ 'Tibet's Three Gorges Dam' starts operation.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 Buckley 2014, p. 52.

- ↑ Pletcher 2010, p. 299.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 Hydroelectric Power Plants in China, Platts.

- ↑ China region completes work on 100-MW Zhikong.

- ↑ Cheng 2011, p. 296.

- ↑ Cheng 2011, p. 297.

- ↑ McCue 2010, p. 43.

- ↑ Damxung Tibet Introduction, CCTV.

- ↑ First drug rehabilitation center in Tibet ... 2009.

- ↑ Zhongwei 2006, p. 474.

- ↑ Buckley 2012, p. 141.

- ↑ Salvacion 2015.

- ↑ Barnett 1996, p. 86.

- ↑ Landon 1905, p. 29.

- ↑ Powers 2007, p. 148.

- ↑ Alexander 2013, p. 34.

- ↑ Historic Dra Yerpa Temple in Tibet, Xinhua.

- ↑ Dorje 1999, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 Buckley 2012, p. 142.

- ↑ Dowman 1988, p. 59.

- ↑ Dowman 1988, p. 40.

- ↑ Dorje 1999, p. 88.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 Nie Tong Temple, CTO.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 Chinese Buddhist temple tour.

- ↑ Lhasa Duilongdeqing County Introduction.

- ↑ McCue 2010, p. 129.

- ↑ Dorje & Kapstein 1991, p. 478.

- ↑ Diemberger 2014, p. 239.

- ↑ Gandain Monastery, China Intercontinental, p. 2.

- ↑ Dorje 1999, p. 113.

- ↑ Bisht 2008, p. 25.

- ↑ Cabezón 2008.

- ↑ Hackett & Bernard 2013, p. 325.

- ↑ Buckley 2012, p. 143.

- ↑ Kelly & Bellezza 2008, p. 113.

- ↑ Fenton 1999, p. 93.

- ↑ Mayhew & Kohn 2005, p. 142.

- ↑ McCue 2010, p. 134.

- ↑ Drikung Thil, Drikung Kagyu Order.

- ↑ Dowman 1988, p. 99.

- ↑ Buckley 2012, p. 174.

- ↑ Dowman 1988, p. 99–100.

- ↑ Mayhew & Kohn 2005, p. 22.

- ↑ Alexander 2013, p. 374.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lhasa (prefecture-level city). |

Sources

- "430 million yuan in place for Lhasa-Gongkar airport expressway". China Tibet Online. 2010-08-02. Retrieved 2015-02-16.

- "A journey in Tibet: Mila Mountain". People's Daily Online. 2012-03-05. Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- Alexander, André (2013). The Traditional Lhasa House: Typology of an Endangered Species. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-90203-0. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- Alsdorf, Douglas; Brown, Larry; Nelson, K. Douglas; Makovsky, Yizhaq; Klemperer, Simon; Zhao, Wenjin (August 1998). "Crustal deformation of the Lhasa terrane, Tibet plateau from Project INDEPTH deep seismic reflection profiles" (PDF). Tectonics 17 (4). Retrieved 2015-02-19.

- An, Caidan (2003). Tibet China: Travel Guide. 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 978-7-5085-0374-5. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Bai, Wanqi; Shang, Erping; Zhang, Yili (2012). "Application of a New Method of Wetland Vulnerability Assessment to the Lhasa River Basin". Resources Science 34 (9). Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Barnett, Robert (1996). Cutting Off the Serpent's Head: Tightening Control in Tibet, 1994-1995. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-166-4. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- "Basic Dazi". Dazi Industry and Information Bureau. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

- Bisht, Ramesh Chandra (2008-01-01). International Encyclopaedia Of Himalayas (5 Vols. Set). Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-8324-265-3. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- "Booming Lhasa Qushui". CCTV: China Central People's Radio. 2003-12-05. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- Brown, Kerry (2013-08-13). "Mining Tibet, Poisoning China". China Digital Times. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Buckley, Michael (2012). Tibet. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-382-5. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- Buckley, Michael (2014-11-11). Meltdown in Tibet: China's Reckless Destruction of Ecosystems from the Highlands of Tibet to the Deltas of Asia. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-137-47472-8. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- Cabezón, José Ignacio (2008). "Introduction to Sera Monastery". THL. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- "Ceramic skill, treasure of herdsmen in Maizhokunggar". China Tibet News. 2015-01-31. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Chellaney, Brahma (2013-07-25). Water: Asia's New Battleground. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1-62616-012-5. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- Cheng, Joseph Y. S. (2011-01-01). Whither China's Democracy? Democratization in China Since the Tiananmen Incident. City University of HK Press. ISBN 978-962-937-181-4. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- "China region completes work on 100-MW Zhikong". HydroWorld. 2007-02-28. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- "Chinese Buddhist temple tour: Lhasa Nie Tong Temple (Dolma Lacan)" (in Chinese). 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2015-02-25.

- Chow, Chung Wah; Eimer, David; Heller, Carolyn B.; Thomas Huhti (2009). China. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74220-325-6.

- "Damxung (当雄县)". Baidu Baike (in Chinese). Baidu. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- "Damxung Land Resources" (in Chinese). Land and Resources Information Center of Tibet Autonomous Region. 2010-08-15. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- "Damxung Mineral Resources" (in Chinese). Land and Resources Information Center of Tibet Autonomous Region. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- Wang Yi Lin (2008-10-07). "Damxung Tibet Introduction" (in Chinese). CCTV. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- "Dazi". Baidu Baike. Baidu. Retrieved 2015-02-07.

- "Dazi Overview". Dazi county government. 2013-07-10. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

- "Джичу". Географическая энциклопедия (Geographical Encyclopedia) (in Russian). Retrieved 2015-02-05.

- Diemberger, Hildegard (2014-03-04). When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty: The Samding Dorje Phagmo of Tibet. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14321-9. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

- Dor, Ji; Zhao, Ping (2000). "Characteristics and Genesis of the Yangbajing Geothermal Field, Tibet" (PDF). Proceedings World Geothermal Congress 2000 (Kyusho - Tohoku, Japan). Retrieved 2015-02-12.

- Dorje, Gyurme; Kapstein, Matthew (1991). The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism: Its Fundamentals and History. 2: Reference Material. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-087-8.

- Dorje, Gyurme (1999). Footprint Tibet Handbook (2 ed.). Bath, England. ISBN 1-900949-33-4.

- Dowman, Keith (1988). The Power-places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim's Guide. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7102-1370-0.

- "Drikung Thil". Drikung Kagyu Order of Tibetan Buddhism. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- "Duilongdeqing County". Administrative divisions Network (in Chinese). Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- "Chengguan District of Lhasa". Baidu Baike. Baidu. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- Fenton, Peter (1999-10-01). Tibetan Healing: The Modern Legacy of Medicine Buddha. Quest Books Theosophical Publishing House. ISBN 978-0-8356-0776-6.

- "First drug rehabilitation center in Tibet to be constructed in Duilongdeqing County". China Tibet Online. 2009-06-29. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- Foster, Simon; Lee, Candice; Lin-Liu, Jen; Beth Reiber, Tini Tran, Lee Wing-sze, Christopher D. Winnan (2012-03-12). Frommer's China. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-23677-2. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- Gandain Monastery. China Intercontinental Press. 1997. ISBN 978-7-80113-312-0. Retrieved 2015-02-07.

- Ge Le; Li Tao (1996). "Rural Urbanization in China’s Tibetan Region: Duilongdeq County as a Typical Example" (PDF). Chinese Sociology and Anthropology 28 (4). Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- "Government Work Report". Linzhou People's Government Office. 2011-03-21. Retrieved 2015-02-15.

- Guan, Steve (2013-12-12). "Tibet commences new hydropower plant". China Coal Resource. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- Guo, Feng Peng (2014-07-19). "Tibet Duilongdeqing county total civilian ecological vanguard striving to protect the mountains". Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- Hackett, Paul G.; Bernard, Theos (2013-08-13). Theos Bernard, the White Lama: Tibet, Yoga, and American Religious Life. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-53037-8. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- Harrison, T.M. (2006-01-01). "Did the Himalaya Extrude from Beneath Tibet?". Channel Flow, Ductile Extrusion and Exhumation in Continental Collision Zones. Geological Society of London. ISBN 978-1-86239-209-0. Retrieved 2015-02-11.

- "Historic Dra Yerpa Temple in Tibet". Global Times. Xinhua. 2012-09-10. Retrieved 2015-02-07.

- Huffman, Brent (2004-03-22). "Bharal, Himalayan blue sheep". Ultimate Ungulate. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- "Hydroelectric Power Plants in China - Tibet". Platts UDI World Electric Power Plants Data Base. 2012-10-03. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- "Inside Nimu". China Tibet Online. Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- J. Gao (2013-06-21). Advances in Climate Change and Global Warming Research and Application: 2013 Edition. ScholarlyEditions. ISBN 978-1-4816-8220-6. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- Johnson, Tim (2011). Tragedy in Crimson: How the Dalai Lama Conquered the World But Lost the Battle with China. Nation Books. ISBN 978-1-56858-649-6. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- Kapstein, Matthew T. (2013-06-05). The Tibetans. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 1-118-72537-9. Retrieved 2015-02-05.

- Kelly, Robert; Bellezza, John Vincent (2008). Tibet. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-569-7. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- Landon, Perceval (1905). Lhasa the Mysterious City. Concept Publishing Company. GGKEY:H0GNCX3YT20. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- LaRocca, Donald J. (2006-01-01). Warriors of the Himalayas: Rediscovering the Arms and Armor of Tibet. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-180-3. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- Leier, Andrew L.; Kapp, Paul; Gehrels, George E.; DeCelles, Peter G. (2007). "Detrital zircon geochronology of Carboniferous–Cretaceous strata in the Lhasa terrane, Southern Tibet" (PDF). Basin Research 19. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2117.2007.00330.x. Retrieved 2015-02-19.

- "Lhasa". Baidu Baike (in Chinese). Baidu. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- "Lhasa Duilongdeqing County Introduction". Lhasa Tourism (in Chinese). Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- "Lhasa Duilongdeqing County Profile". Chinese Government Network (in Chinese). Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- "Lhasa Qushui Introduction" (in Chinese). Chinese Government Network. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- "Lhasa Qushui Introduction" (in Chinese). Lhasa Tourism. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- "Lhasa Railway Station". Tripadvisor. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- "Lhasa Railway Station Duilongdeqing County". China Comfort Travel. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- "Lhasa region map". China Mike. Retrieved 2015-02-28.

- Liebke, Ursina; Appel, Erwin; Ding, Lin; Neumann, Udo; Antolin, Borja; Xu, Qiang (2010). "Position of the Lhasa terrane prior to India–Asia collision derived from palaeomagnetic inclinations of 53 Ma old dykes of the Linzhou Basin: constraints on the age of collision and post-collisional shortening within the Tibetan Plateau". Geophysical Journal International 182 (3). Retrieved 2015-02-19.

- "Lhasa, Tibet Linzhou Hutoushan reservoir is a paradise for photographers". Tibet Travel Web (in Chinese). Retrieved 2015-02-13.

- Li, Chaoliu; Kang, Shichang; Chen, Pengfei; Zhang, Qianggong; Mi, Jue; Gao, Shaopeng; Sillanpää, Mika (2013). "Geothermal spring causes arsenic contamination in river waters of the southern Tibetan Plateau, China". Environmental Earth Sciences 71 (9). Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- Lin, Karen (2013-12-12). "Black-Necked Cranes Flocking Back to Tibet". China Tibet Online. Retrieved 2015-02-13.

- Lin, Tony (2014-05-27). "Duilongdeqing County, Lhasa". Tibet Travel. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- Ling, Haicheng (2005). Buddhism in China. 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 978-7-5085-0840-5. Retrieved 2015-02-15.

- "Linzhou (林周县)". Baidu (in Chinese). Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- "Linzhou County Profile". Lhasa Municipal Bureau of Industry and Information. 2011-06-22. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- "Linzhou Industry News". Lhasa Municipal Bureau of Industry and Information. 2011-06-22. Retrieved 2015-02-15.

- "Linzhou". TibetOL. China Intercontinental Communication Center. Retrieved 2015-02-15.

- Lobsang, Zhaxi; Zhang, Junyi (2003). "Ancient Stone Relief of Kangma". China Tibet Information Center. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- Mayhew, Bradley; Kohn, Michael (2005). Tibet. Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 1-74059-523-8.

- McCue, Gary (2010). Trekking in Tibet: A Traveler's Guide. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-1-59485-411-8. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- Mei, Zhimin (2008-10-06). "Lhasa, Tibet Damxung – 6.6 Earthquake" (in Chinese). China News Network. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- Metcalfe, I (1994). "Late Paleozoic and Mesozoic paleogeography of eastern Pangea and Thethys". In Embry, Ashton F.; Beauchamp, Benoit and Glass, Donald J. Pangea: Global Environments and Resources. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists. ISBN 978-0-920230-57-2.

- "Moderate quake jolts Tibet; no injuries reported". Hindustan Times. 2010-12-01. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- "Mozhugongka County" (in Chinese). China Intercontinental Communication Center. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- "Mozhugongka County" (in Chinese). Mozhugongka County Information Office. 2014-12-19. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- "Mozhugongka County Overview" (in Chinese). Lhasa Municipal Bureau of Industry and Information. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- "Mozhugongka County". TibetOL (in Chinese). Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- "Nie Tong Temple". China Tibet Online. 2005-07-04. Retrieved 2015-02-25.

- "Niyang River". Tibet Vista Travel. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- "Nyêmo County". Baidu Baike (in Chinese). Baidu. Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- "Nyêmo County 2012 Summary of Economic and Social Development". Xinhua. 2013-02-20. Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- "Nyêmo County". haotui.com. Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- "Nyêmo County Overview". Municipal People's Government of Lhasa. 2011-03-15. Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- Ortlam, Dieter (1991). "Hammerschlag-seismische Untersuchungen in Hochgebirgen Nord-Tibets". Z. Geomorphologie (in German) (Berlin/Stuttgart).

- Ozacar, Arda (2015). "Paleotectonic Evolution of Tibet". Retrieved 2015-02-18.

- Pletcher, Kenneth (2010-08-15). The Geography of China: Sacred and Historic Places. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-61530-134-8. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- Pommaret, Françoise (2003). Lhasa in the Seventeenth Century: The Capital of the Dalai Lamas. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-12866-2. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- Powers, John (2007-12-25). Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism. Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 978-1-55939-835-0. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- Qin, Julia (2013-05-10). "Tibet key water-control project to be completed". China Tibet Online. Retrieved 2015-02-05.

- "Qushui & Duilongdeqing County". Scenic Chinese dictionary. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- "Resettlement and railroad construction in Lhasa: new images". International Campaign for Tibet. 2005-04-15. Retrieved 2015-02-14.

- Salvacion, Manny (2015-03-03). "Registered Number of Mobile Phone Users in Tibet Hits Nearly 3 Million". Yibada. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- Sandberg, Graham (1889). "The City of Lhasa". The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art. Leavitt, Trow & Company. Retrieved 2015-02-05.

- "Sanpower Group donated RMB300,000 to Mozhugongka County". Sanpower Group. 2011-09-02. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Shakabpa, Tsepon Wangchuk Deden (2009). One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-17732-9. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

- Shen, Dajun (July 1995). "Research on the rational use of water resources on the Lhasa River, Tibet" (PDF). Modelling and Management of Sustainable Basin-scale Water Resource Systems (Proceedings of a Boulder Symposium (IAHS). Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- Shen, Xianjie (1996-12-01). Crust-Mantle Thermal Structure and Tectonothermal Evolution of the Tibetan Plateau. VSP. ISBN 90-6764-223-1. Retrieved 2015-02-11.

- Shi, Jierui (2011-07-19). "First expressway in Tibet halves time from downtown Lhasa to airport". Retrieved 2015-02-16.

- Tabulation on Nationalities of 2000 Population Census of China (2000年人口普查中国民族人口资料)., 2 volumes, Beijing: Nationalities Publishing House (民族出版社), 2003, ISBN 7-105-05425-5

- "Tibet". chinamaps.org. Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- "Tibet Maps". ChinaTourGuide. Retrieved 2015-02-28.

- "'Tibet's Three Gorges Dam' starts operation". China Daily. 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2015-02-05.

- "Tibetans rebuked for protesting poisoning by Chinese mines". Tibetan Review. 2014-10-01. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Waddell, Laurence A. (1905). Lhasa and Its Mysteries: With a Record of the Expedition of 1903-1904. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60206-724-0. Retrieved 2015-02-05.

- Wan, Tianfeng (2010). The Tectonics of China: Data, Maps and Evolution. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-11866-1.

- Winn, Pete (2015). "Geology and Geography of the Reting Tsangpo and Lhasa River (Kyi Qu) in Tibet". Exploring the Rivers of Western China. Earth Science Expeditions. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- "XE Currency Table: CNY - Chinese Yuan Renminbi". XE. Retrieved 2015-02-16.

- "Yangbajing". Ministry of Culture, P.R.China. Retrieved 2015-02-11.

- "Yangpachen Monastery". Meiya Travel. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- Yeh, Emily T.; Henderson, Mark (December 2008). "Interpreting Urbanization in Tibet". Journal of the International Association of Tibetan Studies 4. Retrieved 2015-02-12.

- Yin, Jixiang; Xu, Juntao; Liu, Chengjie (1988-12-12). "The Tibetan Plateau: Regional Stratigraphic Context and Previous Work". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences (The Royal Society) 327 (1594: The Geological Evolution of Tibet: Report of the 1985 Royal Society -- Academia Sinica Geotraverse of Qinghai-Xizang Plateau). Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Zhang, Z.M.; Dong, X.; Santosh, M.; Zhao, G.C (January 2014). "Metamorphism and tectonic evolution of the Lhasa terrane, Central Tibet". Gondwana Research 25 (1). Retrieved 2015-02-18.

- Zhang, Tianhua; Huang, Qiongzhong (1997). "Pollution of Geothermal Wastewater Produced by Tibet Yangbajin Geothermal Power Station". Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- Zhang, Ming-tao; Tong, Wei (1982). "The Hydrothermal Activities and Exploitation Potentiality of Geothermal Energy in Southern Xizang (Tibet)". Energy, Resources and Environment: Papers Presented at the First U.S.-China Conference on Energy, Resources and Environment, 7-12 November 1982, Beijing, China. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-1-4831-3583-0. Retrieved 2015-02-11.

- Zheng, Peng (2007-09-24). "Lhasa River Zhi Kong hydroelectric power station put into operation". China Tibet Information Center. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- Zhongwei, Zhao (September 2006). "Income Inequality, Unequal Health Care Access, and Mortality in China". Population and Development Review (Population Council) 32 (3). Retrieved 2015-02-09.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||

.jpg)