Lewis Valentine

- For the Police Commissioner of New York City, see Lewis J. Valentine.

Lewis Edward Valentine (1 June 1893 – March 1986) was a Welsh politician, Baptist pastor, author, editor, and Welsh-language activist.

Early life

Valentine was born in Llanddulas, Conwy, the son of Samuel Valentine, a limestone quarryman, and his wife Mary. He began studying to go into the ministry of the Baptist church at the University College of North Wales, Bangor but his studies were curtailed due to the First World War.

Founding Plaid Cymru

His experiences in World War I, and his sympathy for the cause of Irish independence, brought him to Welsh nationalism, and in 1925 he met with Saunders Lewis, H. R. Jones, and others at a 1925 National Eisteddfod meeting, held in Pwllheli, Gwynedd, with the aim of establishing a Welsh party.[1]

Discussions for the need of a "Welsh party" had been circulating since the 19th century.[2] With the generation or so before 1922 there "had been a marked growth in the constitutional recognition of the Welsh nation," wrote historian Dr. John Davies.[3] By 1924 there were people in Wales "eager to make their nationality the focus of Welsh politics.[4]"

The principal aim of the new party would be to foster a Welsh speaking Wales.[5] To this end it was agreed that party business be conducted in Welsh, and that members sever all links with other British parties.[6] Valentine, Lewis and others insisted on these principles before they would agree to the Pwllheli conference.

According to the 1911 census, out of a population of just under 2.5 million, 43.5% of the total population of Wales spoke Welsh as a primary language.[7] This was a decrease from the 1891 census with 54.4% speaking Welsh out of a population of 1.5 million.[8]

With these prerequisites Lewis condemned "'Welsh nationalism' as it had hitherto existed, a nationalism characterized by inter-party conferences, an obsession with Westminster and a willingness to accept a subservient position for the Welsh language," wrote Dr. Davies.[9] It may be because of these strict positions that the party failed to attract politicians of experience in its early years.[10] However, the party's members believed its founding was an achievement in itself; "merely by existing, the party was a declaration of the distinctiveness of Wales," wrote Dr. Davies.[11]

During the inter-war years, Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru was most successful as a social and educational pressure group rather than as a political party.[12]

Tân yn Llŷn 1936

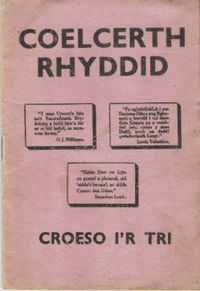

Plaid Cenedlaethol Cymru's 1936 political pamphlet

Welsh nationalism was ignited in 1936 when the UK government settled on establishing a bombing school at Penyberth on the Llŷn peninsula in Gwynedd. The events surrounding the protest, known as Tân yn Llŷn (Fire in Llŷn), helped define Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru.[13] The UK government settled on Llŷn as the site for its new bombing school after similar locations Northumberland and Dorset were met with protests.[14]

However, UK Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin refused to hear the case against the bombing school in Wales, despite a deputation representing half a million Welsh protesters.[15] Protest against the bombing school was summed up by Lewis when he wrote that the UK government was intent upon turning one of the 'essential homes of Welsh culture, idiom, and literature' into a place for promoting a barbaric method of warfare.[16] Construction of the bombing school building began exactly 400 years after the first Act of Union annexing Wales into England.[17]

On 8 September 1936 the bombing school building was set on fire and in the investigations which followed Saunders Lewis, Lewis Valentine, and D.J. Williams claimed responsibility.[18] The trial at Caernarfon failed to agree on a verdict and the case was sent to the Old Bailey in London. The "Three" were sentenced to nine months imprisonment in Wormwood Scrubs, and on their release they were greeted as heroes by fifteen thousand Welsh at the Pavilion Caernarfon.[19]

Many Welsh were angered by the Judge's scornful treatment of the Welsh language, by the decision to move the trial to London, and by the decision of University College, Swansea, to dismiss Lewis from his post before he had been found guilty.[20] Dafydd Glyn Jones wrote of the fire that it was "the first time in five centuries that Wales struck back at England with a measure of violence... To the Welsh people, who had long ceased to believe that they had it in them, it was a profound shock."[21]

However, despite the acclaim the events of Tân yn Llŷn generated, by 1938 Lewis' concept of perchentyaeth was firmly rejected as not a fundamental tenet of the party. In 1939 Lewis resigned as Plaid Genedleathol Cymru president citing that Wales was not ready to accept the leadership of a Roman Catholic.[22]

Lewis was the son and grandson of prominent Welsh Calvinistic Methodist ministers. In 1932, he converted to Roman Catholicism.

Second World War

Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru members were free to choose for themselves their level of support for the war effort. Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru was officially neutral regarding involvement the Second World War, which Valentine, Lewis and other leaders considered a continuation of the First World War. Central to the neutrality policy was the idea that Wales, as a nation, had the right to decide independently on its attitude towards war,[23] and the rejection of other nations to force Welshmen to serve in their armed forces.[24] With this challenging and revolutionary policy party leaders hoped a significant number of Welshmen would refuse to join the British Army.[25]

Lewis and other party members were attempting to strengthen loyalty to the Welsh nation "over the loyalty to the British State.[26]" Lewis argued "The only proof that the Welsh nation exists is that there are some who act as if it did exist.[27]"

However, most party members who claimed conscientious objection status did so in the context of their moral and religious beliefs, rather than on political policy.[28] Of these almost all were exempt from military service. About 24 party members made politics their sole grounds for exemption, of which twelve received prison sentences.[29] For Lewis, those who objected proved that the assimilation of Wales was "being withstood, even under the most extreme pressures.[30]"

Pastor, author, and editor

As a pastor he served church in north Wales and edited the Baptist quarterly magazine, Seren Gomer, from 1951 to 1975. He also wrote of his experience in the war in Dyddiadur milwr (=A soldier's diary), 1988.

Valentine is also famed as the writer of the hymn Gweddi dros Gymru ("A prayer for Wales"), usually sung to the tune of Jean Sibelius's Finlandia Hymn. This is considered by some to be the second Welsh national anthem, and has been recorded and widely performed by Dafydd Iwan.

References

- ↑ John Davies, A History of Wales, Penguin, 1994, ISBN 0-14-014581-8, Page 547

- ↑ Davies, op cit, pages 415, 454

- ↑ Davies, op cit, Page 544

- ↑ Davies, op cit, Page 547

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 548

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 548

- ↑ BBCWales History extracted 12-03-07

- ↑ BBCWales history extracted 12-03-07

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 548

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 548

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 548

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 591

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 593

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 592

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 592

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 592

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 592

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 592

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 592

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 593

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 593

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 593

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 598

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 598

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 599

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 598

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 599

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 599

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 599

- ↑ Davies, op cit, page 599

- Valentine, Lewis (1893–1986). In Meic Stephens (Ed.) (1998), The new companion to the literature of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-1383-3.

- Vittle, Arwel. Valentine: cofiant Lewis Valentine. (2006). Tal-y-bont: Y Lolfa. ISBN 0-86243-929-9.

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by New position |

President of Plaid Cymru 1925–1926 |

Succeeded by Saunders Lewis |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||