Leucine

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Leucine | |||

| Other names

2-Amino-4-methylpentanoic acid | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 61-90-5 | |||

| ChEBI | CHEBI:57427 | ||

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL291962 | ||

| ChemSpider | 5880 | ||

| DrugBank | DB01746 | ||

| |||

| Jmol-3D images | Image | ||

| KEGG | D00030 | ||

| PubChem | 6106 | ||

| |||

| UNII | GMW67QNF9C | ||

| Properties | |||

| Molecular formula |

C6H13NO2 | ||

| Molar mass | 131.17 g·mol−1 | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.36 (carboxyl), 9.60 (amino)[1] | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |||

| Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas | ||

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |||

| Except where noted otherwise, data is given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

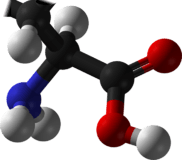

Leucine (abbreviated as Leu or L)[2] is a branched-chain α-amino acid with the chemical formula HO2CCH(NH2)CH2CH(CH3)2. Leucine is classified as a hydrophobic amino acid due to its aliphatic isobutyl side chain. It is encoded by six codons (UUA, UUG, CUU, CUC, CUA, and CUG) and is a major component of the subunits in ferritin, astacin, and other 'buffer' proteins. Leucine is an essential amino acid, meaning that the human body cannot synthesize it, and it therefore must be ingested.

Biosynthesis

As an essential amino acid, leucine cannot be synthesized by animals. Consequently, it must be ingested, usually as a component of proteins. In plants and microorganisms, leucine is synthesised from pyruvic acid by a series of enzymes:[3]

- Acetolactate synthase

- Acetohydroxy acid isomeroreductase

- Dihydroxyacid dehydratase

- α-Isopropylmalate synthase

- α-Isopropylmalate isomerase

- Leucine aminotransferase

Synthesis of the small, hydrophobic amino acid valine also includes the initial part of this pathway.

Biology

Leucine is utilized in the liver, adipose tissue, and muscle tissue. In adipose and muscle tissue, leucine is used in the formation of sterols, and the combined usage of leucine in these two tissues is seven times greater than its use in the liver.[4]

Leucine is the only dietary amino acid that has the capacity to stimulate muscle protein synthesis.[5] As a dietary supplement, leucine has been found to slow the degradation of muscle tissue by increasing the synthesis of muscle proteins in aged rats.[6] However, results of comparative studies are conflicted. Long-term leucine supplementation does not increase muscle mass or strength in healthy elderly men.[7] More studies are needed, preferably those which utilize an objective, random sample of society. Factors such as lifestyle choices, age, gender, diet, exercise, etc. must be factored into the analyses in order to isolate the effects of supplemental leucine as a standalone, or if taken with other branched chain amino acids (BCAAs). Until then, dietary supplemental leucine cannot be associated as the prime reason for muscular growth or optimal maintenance for the entire population.

While once seen as an important part of the three branch chained amino acids in sports supplements, leucine has since earned more attention on its own as a catalyst for muscle growth and muscular insurance. Supplement companies once marketed the "ideal" 2:1:1 ratio of leucine, isoleucine and valine; but with furthered evidence that leucine is the most important amino acid for muscle building, it has become much more popular as the primary ingredient in dietary supplements with a 4:1:1 ratio.[8]

Leucine potently activates the mammalian target of rapamycin kinase that regulates cell growth. Infusion of leucine into the rat brain has been shown to decrease food intake and body weight via activation of the mTOR pathway.[9]

Leucine toxicity, as seen in decompensated maple syrup urine disease (MSUD), causes delirium and neurologic compromise, and can be life-threatening. More studies need to be done on liver overactivity due to taking supplemental leucine.

Excess leucine may be a cause of pellagra, whose main symptoms are "the four D's": diarrhea, dermatitis, dementia and death,[10] though the relationship is unclear.[11]

In yeast genetics, mutants with a defective gene for leucine synthesis (leu2) are transformed with a plasmid that contains a working leucine synthesis gene (LEU2) and grown on minimal media. Leucine synthesis then becomes a useful selectable marker.

Dietary aspects

| Food | g/100g |

|---|---|

| Soybeans, mature seeds, raw | 2.97 |

| Beef, round, top round, separable lean and fat, trimmed to 1/8" fat, select, raw | 1.76 |

| Peanuts | 1.672 |

| Salami, pork | 1.63 |

| Fish, salmon, pink, raw | 1.62 |

| Wheat germ | 1.571 |

| Almonds | 1.488 |

| Chicken, broilers or fryers, thigh, meat only, raw | 1.48 |

| Chicken egg, yolk, raw, fresh | 1.40 |

| Oat | 1.284 |

| Beans, pinto, cooked | 0.765 |

| Lentils, cooked | 0.654 |

| Chickpea, cooked | 0.631 |

| Corn, yellow | 0.348 |

| Cow milk, whole, 3.25% milk fat | 0.27 |

| Rice, brown, medium-grain, cooked | 0.191 |

| Milk, human, mature, fluid | 0.10 |

Betaines

Chemical properties

Leucine is a branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) since it possesses an aliphatic side-chain that is non-linear.

Racemic leucine had been subjected to circularly polarized synchrotron radiation in order to better understand the origin of biomolecular asymmetry. An enantiomeric enhancement of 2.6% had been induced, indicating a possible photochemical origin of biomolecules' homochirality.[13]

Food additive

As a food additive, L-Leucine has E number E641 and is classified as a flavor enhancer.[14]

See also

- Leucines, description of the isomers of leucine

- Photo-reactive leucine

References

- ↑ Dawson, R.M.C., et al., Data for Biochemical Research, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1959.

- ↑ IUPAC-IUBMB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". Recommendations on Organic & Biochemical Nomenclature, Symbols & Terminology etc. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ↑ Nelson, D. L.; Cox, M. M. "Lehninger, Principles of Biochemistry" 3rd Ed. Worth Publishing: New York, 2000. ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

- ↑ J. Rosenthal, et al. Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. "Metabolic fate of leucine: A significant sterol precursor in adipose tissue and muscle". American Journal of Physiology Vol. 226, No. 2, p. 411-418. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ↑ Etzel MR (2004). "Manufacture and use of dairy protein fractions". The Journal of Nutrition 134 (4): 996S–1002S. PMID 15051860.

- ↑ L. Combaret, et al. Human Nutrition Research Centre of Clermont-Ferrand. "A leucine-supplemented diet restores the defective postprandial inhibition of proteasome-dependent proteolysis in aged rat skeletal muscle". Journal of Physiology Volume 569, issue 2, p. 489-499. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ↑ Am J Clin Nutr. (2009 issue=May 89(5)). "Long-term leucine supplementation does not increase muscle mass or strength in healthy elderly men". Am J Clin Nutr 89 (5): 1468–75. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.26668. PMID 19321567. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Leucine Awesome, Scientists Say". Sports Supplement Reviewer. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- ↑ Cota D, Proulx K, Smith KA, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Woods SC, Seeley RJ (2006). "Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake". Science 312 (5775): 927–930. doi:10.1126/science.1124147. PMID 16690869.

- ↑ Hegyi J, Schwartz R, Hegyi V (2004). "Pellagra: dermatitis, dementia, and diarrhea". Int J Dermatol 43 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01959.x. PMID 14693013.

- ↑ Bapurao S, Krishnaswamy K (1978). "Vitamin B6 nutritional status of pellagrins and their leucine tolerance". Am J Clin Nutr 31 (5): 819–24. PMID 206127.

- ↑ National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ↑ Meierhenrich: Amino acids and the asymmetry of life, Springer-Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-540-76885-2.

- ↑ Winter, Ruth (2009). A consumer's dictionary of food additives (7th ed. ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0307408922.

External links

- Leucine biosynthesis

- Leucine prevents muscle loss in rats

- Leucine helps regulate appetite in rats

- Combined ingestion of protein and free leucine with carbohydrate increases postexercise muscle protein synthesis in vivo in male subjects

- A leucine-supplemented diet restores the defective postprandial inhibition of proteasome-dependent proteolysis in aged rat skeletal muscle

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||