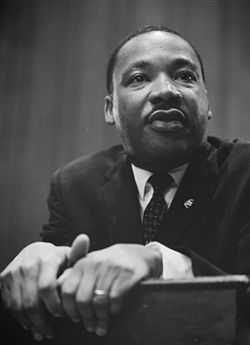

Letter from Birmingham Jail

The Letter from Birmingham Jail (also known as "Letter from Birmingham City Jail" and "The Negro Is Your Brother") is an open letter written on April 16, 1963, by Martin Luther King, Jr. The letter defends the strategy of nonviolent resistance to racism. It says that people have a moral responsibility to break unjust laws, and to take direct action rather than waiting potentially forever for justice to come through the courts. Responding to being referred to as an "outsider", he wrote that “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere“.

The letter was widely published and became an important text for the American Civil Rights Movement of the early 1960s.

Background

The Birmingham Campaign began on April 3, 1963, with coordinated marches and sit-ins against racism and racial segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. The nonviolent campaign was coordinated by the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights and King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference. On April 10, Circuit Judge W. A. Jenkins issued a blanket injunction against "parading, demonstrating, boycotting, trespassing and picketing". Leaders of the campaign announced they would disobey the ruling.[1] On April 12, King was roughly arrested with SCLC activist Ralph Abernathy, ACMHR and SCLC official Fred Shuttlesworth, and other marchers while thousands of African Americans dressed for Good Friday looked on.[2]

King met with unusually harsh conditions in the Birmingham jail.[3] An ally smuggled in a newspaper from April 12, which contained "A Call for Unity": a statement made by eight white Alabama clergymen against King and his methods.[2] The letter provoked King, and he began to write a response on the newspaper itself. King writes in Why We Can't Wait: “Begun on the margins of the newspaper in which the statement appeared while I was in jail, the letter was continued on scraps of writing paper supplied by a friendly black trusty, and concluded on a pad my attorneys were eventually permitted to leave me.”[4]

Summary and themes

The letter responded to several criticisms made by the "A Call for Unity" clergymen, who agreed that social injustices existed but argued that the battle against racial segregation should be fought solely in the courts, not the streets. As a minister, King responded to these criticisms on religious grounds. As an activist challenging an entrenched social system, he argued on legal, political, and historical grounds. As an African American, he spoke of the country’s oppression of black people, including himself. As an orator, he used many persuasive techniques to reach the hearts and minds of his audience. Altogether, King’s letter was a powerful defense of the motivations, tactics, and goals of the Birmingham Campaign and the Civil Rights movement more generally.

King began the letter by responding to the criticism that he and his fellow activists were “outsiders” causing trouble in the streets of Birmingham. To this, King referred to his responsibility as the leader of the SCLC, which had numerous affiliated organizations throughout the South. “I was invited”[5] by our Birmingham affiliate “because injustice is here,”[5] in what is probably the most racially divided city in the country, with its brutal police, unjust courts, and many “unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches.”[6] Referring to his belief that all communities and states were interrelated, King wrote, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly… Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.”[7] King also warned that if white people successfully rejected his nonviolent activists as rabble-rousing outside agitators, millions of African Americans probably would “seek solace and security in black nationalist ideologies, a development that will lead inevitably to a frightening racial nightmare.”[8]

The clergymen also disapproved of tensions created by public actions such as sit-ins and marches. To this, King confirmed that he and his fellow demonstrators were indeed using nonviolent direct action in order to create “constructive” tension.[5] This tension was intended to compel meaningful negotiation with the white power structure, without which true civil rights could never be achieved. Citing previous failed negotiations, King wrote that the black community was left with “no alternative.”[5] “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”[9]

The clergymen also disapproved of the timing of public actions. In response, King said that recent decisions by the SCLC to delay its efforts for tactical reasons showed they were behaving responsibly. He also referred to the broader scope of history, when "'Wait' has almost always meant 'Never.'"[7] Declaring that African Americans had waited for these God-given and constitutional rights long enough, King quoted Chief Justice Earl Warren, who said in 1958 that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”[7] Listing numerous ongoing injustices toward black people, including himself, King said, “Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, ‘Wait.’”[10] Along similar lines, King also lamented the “myth concerning time,” by which white moderates assumed that progress toward equal rights was inevitable, so assertive activism was unnecessary.[11] King called it a “tragic misconception of time” to assume that its mere passage “will inevitably cure all ills.”[11] Progress takes time as well as the “tireless efforts” of dedicated people of good will.[11]

Against the clergymen’s assertion that demonstrations could be illegal, King argued that not only was civil disobedience justified in the face of unjust laws, but it was necessary and even patriotic. “I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.”[12] Citing St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, Martin Buber, and Paul Tillich—and examples from the past and present—King described what makes laws just or unjust. For example, “A law is unjust if it is inflicted on a minority that, as a result of being denied the right to vote, had no part in enacting or devising the law.”[13] Alabama has used “all sorts of devious methods” to deny its black citizens their right to vote and thus preserve its unjust laws and broader system of white supremacy.[13] Segregation laws are immoral and unjust “because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority.”[14] Even some just laws, such as permit requirements for public marches, are unjust when used to uphold an unjust system.

King addressed the accusation that the Civil Rights movement was "extreme," first disputing the label but then accepting it. Jesus and other great reformers were extremists: "So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love?"[15] King's discussion of extremism implicitly responded to numerous "moderate" objections to the ongoing movement, such as President Eisenhower's claim that he could not meet with civil rights leaders because doing so would require him to meet with the Ku Klux Klan.[16]

King expressed general frustration with both white moderates and certain “opposing forces in the Negro community.”[17] He wrote that white moderates, including clergymen, posed a challenge comparable to that of white supremacists, in the sense that, “Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.”[18] King asserted that the white church needed to take a principled stand or risk being “dismissed as an irrelevant social club.”[19] Regarding the black community, King wrote that we need not follow “the ‘do-nothingism’ of the complacent nor the hatred and despair of the black nationalist.”[17]

In closing the letter, King criticized the clergy’s praise of the Birmingham police for maintaining order nonviolently. Recent public displays of nonviolence by the police were in stark contrast to their typical treatment of black people, and, as public relations, helped “to preserve the evil system of segregation.”[19] Not only is it wrong to use immoral means to achieve moral ends, but also “to use moral means to preserve immoral ends.”[20] Instead of the police, King praised the nonviolent demonstrators in Birmingham, “for their sublime courage, their willingness to suffer and their amazing discipline in the midst of great provocation. One day the South will recognize its real heroes.”[21]

Publication

King wrote the letter on the margins of a newspaper, which was the only paper available to him, and then gave bits and pieces of the letter to his lawyers to take back to movement headquarters, where the Reverend Wyatt Walker began compiling and editing the literary jigsaw puzzle.[22]

An editor at the New York Times Magazine, Harvey Shapiro, asked King to write his letter for publication in the magazine, but the Times chose not to publish it.[23] Extensive excerpts from the letter were published, without King's consent, on May 19, 1963 in the New York Post Sunday Magazine.[24] The letter was first published as "Letter from Birmingham Jail" in the June 1963 issue of Liberation,[25] the June 12, 1963 edition of The Christian Century,[26] and in the June 24, 1963 issue of The New Leader. The letter gained more popularity as summer went on, and was reprinted in the July Atlantic Monthly as "The Negro Is Your Brother."[27] King included a version of the full text in his 1964 book Why We Can't Wait.[28]

A 1999 study found that the essay was highly anthologized in that it was reprinted 50 times in 325 editions of 58 readers published between 1964 and 1996 that were intended for use in college-level composition courses.[29]

References

- ↑ "Negroes To Defy Ban", Tuscaloosa News, 11 April 1963.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Rieder, Gospel of Freedom (2013), ch. "Meet Me in Galilee".

- ↑ Rieder, Gospel of Freedom (2013), ch. "Meet Me in Galilee". "King was placed alone in a dark cell, with no mattress, and denied a phone call. Was Connor's aim, as some thought, to break him?"

- ↑ King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 64

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 65.

- ↑ King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 66.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 King, Martin Luther. "Letter from a Birmingham Jail". Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ↑ King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 76.

- ↑ King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 68.

- ↑ King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 69.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 74.

- ↑ King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 72.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 71.

- ↑ King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 70-71.

- ↑ " "Letter from Birmingham Jail" (1963)", The King Center, accessed 27 October 2012.

- ↑ Anna McCarthy, The Citizen Machine: Governing by Television in 1950s America, New York: The New Press, 2010, p. 16.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 75.

- ↑ King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 73.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 80.

- ↑ King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 82.

- ↑ King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 83.

- ↑ Wyatt Walker interview by Andrew Manis at New Caanan Baptist Church, New York City, April 20, 1989, page 24. Transcription held at Birmingham Public Library, Birmingham, Alabama.

- ↑ Margalit Fox (January 7, 2013). "Harvey Shapiro, Poet and Editor, Dies at 88". New York Times.

- ↑ Bass, S. Jonathan (2001). Blessed are the peacemakers: Martin Luther King, Jr., eight white religious leaders, and the "Letter from Birmingham Jail". Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2655-1. p. 140

- ↑ Liberation: An Independent Monthly. June, 1963 (page 10-16, 23)

- ↑ Reprinted in Reporting Civil Rights, Part One - (page 777- 794) - American Journalism 1941 - 1963. The Library of America

- ↑ Rieder, Gospel of Freedom (2013), ch. "Free at Last?"

- ↑ In a footnote introducing this chapter of the book, King wrote, “Although the text remains in substance unaltered, I have indulged in the author’s prerogative of polishing it." (King (1964), Why We Can't Wait, p. 64.)

- ↑ Bloom, L. Z. (1999). "The Essay Canon" (PDF). College English 61 (4): 401–430. doi:10.2307/378920. Retrieved 18 Jan 2012.

Bibliography

- Gilbreath, Edward (2013). Birmingham Revolution. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-3769-4.

- Fulkerson, R. P. (1979). "The public letter as a rhetorical form: Structure, logic, and style in King's "Letter from Birmingham Jail"". Quarterly Journal of Speech 65 (2): 121–136. doi:10.1080/00335637909383465.

- King, Martin Luther, Jr. (1964). Why We Can't Wait. New York, NY: Signet Classic, 2000. ISBN 0451527534.

- Oppenheimer, D. B. (1993). "Martin Luther King, Walker v. City of Birmingham, and the Letter from Birmingham Jail" (PDF). U.C. Davis Law Review 26 (4): 791–833.

- Snow, M. (1985). "Martin Luther King's "Letter from Birmingham Jail" as Pauline epistle". Quarterly Journal of Speech 71 (3): 318–334. doi:10.1080/00335638509383739.

- Rieder, Jonathan (2013). Gospel of Freedom: Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Letter From Birmingham Jail. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1620400586

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Letter from a Birmingham Jail |

- A Film on the Letter from Birmingham Jail

- "Letter from Birmingham Jail" (typo-ridden, full-text edition at Bates College)

- Letter from Birmingham Jail pdf format from The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford.

- "Statement by Alabama Clergymen", referred to above as "Call for Unity"

- EDSITEment lesson on Letter from a Birmingham Jail

- Letter from Birmingham Jail article at BhamWiki.com

- Letter from Birmingham Jail article, Encyclopedia of Alabama

- Walker v. Birmingham with injunction against protest in Appendix