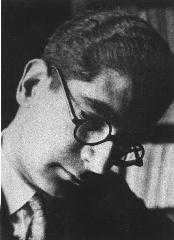

Leone Ginzburg

| Leone Ginzburg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

4 April 1909 Odessa, Russian Empire |

| Died |

5 February 1944 (aged 34) Rome, Kingdom of Italy |

| Occupation | author, journalist, teacher, anti-fascist activist |

| Nationality | Italian |

Leone Ginzburg (Italian: [leˈone ˈɡintsburɡ]; 4 April 1909 – 5 February 1944) was an Italian editor, writer, journalist and teacher, as well as an important anti-fascist political activist and a hero of the resistance movement. He was the husband of the renowned author Natalia Ginzburg and the father of the historian Carlo Ginzburg.

Early life and career

Ginzburg was born in Odessa to a Jewish family, and moved with them, first to Berlin and later to Turin at a very young age. He studied at the Massimo d’Azeglio liceo in Turin . This school molded a group of intellectuals and political activists who would fight Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime and, eventually, help create the post-war democratic Italy. His classmates included such notable intellectuals as Norberto Bobbio, Piero Gobetti, Cesare Pavese, Giulio Einaudi, Massimo Mila, Vittorio Foa, Giancarlo Pajetta and Felice Balbo.

In the early 1930s, Ginzburg taught Slavic Languages and Russian Literature at the University of Turin, and was credited with helping to introduce Russian authors to the Italian public. In 1933, Ginzburg co-founded, with Giulio Einaudi, the publishing house Einaudi. He lost his teaching position in 1934, having refused to swear an oath of allegiance imposed by the Fascist regime.[1]

Persecution and internal exile

Soon after this, he and 14 other young Turinese Jews, including Sion Segre Amar, were arrested for complicity in the so-called "Ponte Tresa Affair" (they were carrying anti-fascist literature over the border from Switzerland), but Ginzburg's sentence was light. He was arrested again in 1935 for his activities as leader (with Carlo Levi) of the Italian branch of Giustizia e Libertà,[2] the Justice and Freedom Party, which Carlo Rosselli had founded in Paris in 1929.

In 1938 he married Natalia Ginzburg. The same year he lost his Italian citizenship when the Fascist regime introduced antisemitic racial laws.[1] In 1940, the Ginzburgs received the fascist punishment known as confino, or internal exile, to a remote, impoverished village, in their case Pizzoli in the Abruzzi, where they stayed from 1940-1943.[3]

Somehow, Leone was able to continue his work as head of the Einaudi publishing house throughout the period. In 1942, he co-founded the clandestine Partito d'Azione[4] or "Action Party", a party of the democratic resistance. He also edited their newspaper L'Italia Libera.[5]

Capture and murder

In 1943, after the Allied invasion of Sicily and the fall of Mussolini, Leone went to Rome, leaving his family in the Abruzzi. When Nazi Germany invaded in September, Natalia Ginzburg and their three children fled Pizzoli, simply climbing aboard a German truck and telling the driver that they were war refugees who had lost their papers. They met with Leone and went into hiding in the capital.

On 20 November 1943, Leone – who now used the false name Leonida Gianturco – was arrested by the Italian police in a clandestine printshop of the newspaper L'Italia Libera. He was taken to the German section of the Regina Coeli prison.[1][3] They subjected him to severe torture. On 5 February 1944 he died there from the injuries he received; he was just 34.[5]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 (Italian) Short biography of Leone Ginzburg, Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d’Italia (ANPI) (accessed October 30, 2010)

- ↑ Giustizia e libertà at www.pbmstoria.it

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Biography of Natalia Ginzburg, Rai International (accessed October 30, 2010)

- ↑ Partito d'azione (1942-1947) at www.pbmstoria.it

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Opposition to Fascism, Memorial Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison

References

- Natalia Ginzburg, All Our Yesterdays

- Natalia Ginzburg, The Things We Used To Say

- Susan Zuccotti, The Italians and the Holocaust: Persecution, Rescue, and Survival, University of Nebraska Press

External links

- Books of the Times; Richard Bernstein, "Telling the Bigger Story With the Small Details", The New York Times, August 4, 1999