Lenton Priory

|

The remains of a stone column from the priory | |

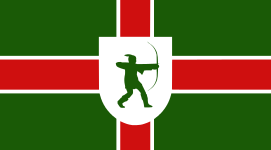

Location within Nottingham | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Cluniac |

| Established | C.1102-8 |

| Disestablished | 1538 |

| Mother house | Cluny Abbey |

| Dedicated to | Holy Trinity |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | William Peverel |

| Site | |

| Location | Lenton, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire |

| Coordinates | 52°56′37″N 1°10′43″W / 52.943611°N 1.178611°WCoordinates: 52°56′37″N 1°10′43″W / 52.943611°N 1.178611°W |

| Grid reference | SK5518938819 |

Lenton Priory was a Cluniac monastic house, founded by William Peverel in the early 12th century. The exact date of foundation is unknown but 1102-8 is frequently quoted. The priory was granted a large endowment of property in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire by its founder, however part of this property became the cause of violent disagreement following its seizure by the crown and its reassignment to Lichfield Cathedral. The priory was home mostly to French monks until the late 14th century when the priory was freed from the control of its foreign mother-house. From the 13th-century the priory struggled financially and was noted for "its poverty and indebtedness". The priory was dissolved as part of King Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries.

History

Foundation

Lenton priory was established in Lenton, Nottingham, around 1½ miles south-west of Nottingham. The priory was founded by William Peverel around 1102-8, and dedicated to the Holy Trinity. The charter of foundation states that Peverel founded the charter "out of love of divine worship and for the good of the souls of his lord King William, of his wife Queen Matlida, of their son King William and of all their and his ancestors". The priory was an alien establishment (one which owed allegiance to a foreign mother house). Lenton's mother-house was Cluny Abbey in France. Usually a priory would pay a proportion of its income to its mother-house; however, Peverel established in the foundation charter that Lenton Priory would be free from the obligation to pay tribute to Cluny, "save the annual payment of a mark of silver as an acknowledgement".[1]

William Peverel gave Lenton Priory a substantial endowment which included: the townships of Lenton, Keighton, Morton and Radford (all in Nottingham), Courteenhall, Northamptonshire, and all of their appurtenances and seven mills; land and woodland in Newthorpe and Papplewick; control of the churches of St. Mary, St. Peter and St. Nicholas, all in Nottingham; the churches at Langar, Linby and Radford; the tithes raised from Peverel's fisheries throughout Nottingham; portions of the tithes from his lands throughout the Peak District including those from Ashford, Bakewell, Bradwell, Buxton, Callow, Chelmorton, Cowdale, Darnall, Dunningestede, Fernilee, Holme, Hucklow, Newbold, Quatford, Shallcross, Stanton, Sterndale, Tideswell and Wormhill; all the tithes raised from his colts and fillies in his stud-farms in the Peak District; the tithes from the lead and venision from his lands in Derbyshire; part of the tithes from Blisworth and Duston and the churches of Courteenhall, Harlestone, Irchester and Rushden, all in Northamptonshire; and the church at Foxton, in Leicestershire.[1]

Although it is believed Peverel did give theses gifts to the priory, the charter of foundation which documents these gifts is believed to be a forgery. The dates on the charter are implausible and the document is believed not to be contemporary.[1]

In the 13th century the priory received a gift from Philip Marc, King John's sheriff in Nottingham, with the condition that the priory look after his body and soul.[2]

The priory was given Royal Confirmation Charters by King Henry I, King Stephen, King Henry II and King John. These charters confirm the priory's earlier endowments and reveals additional gifts including: The church of Wigston in Leicestershire by Robert de Beaumont, 1st Earl of Leicester; tithes from the Peak Forest, Derbyshire, by William de Ferrers; the churches of Ossington, Nottinghamshire and Horsley, Derbyshire, and half of the church of Cotgrave, Notts, by Hugh de Buron and his son Hugh Meschines; the church of Nether Broughton, Leics (and its appurtenances, a chapel and 15 acres of land) by Richard Bussell; The Manors of Holme and Dunston, both in Derbyshire, by Matthew de Hathersage; and a moiety of the church of Attenborough, Nottinghamshire, "the land of Reginald in Chilwell", Barton in Fabis church, and part of the tithes in Bunny and Bradmore, by Odo de Bunny.[1]

King Henry II's first charter granted the priory freedom from taxes, tolls, and customs duties. The second charter he granted them an eight-day fair to celebrate St. Martin's Day. Henry III's charter extended this fair to twelve days in length.[1] In 1199 King John issued a charter allowing the monks to take a cart of deadwood from "the forest of Bestwood" every day. In another charter towards the end of his reign, King John granted the monks game ("harts, hinds, bucks, does, wild boars, and hares") from the royal forests in Nottingham and Derby.[1]

Endowment disputes

The priory had severe ongoing problems with Peverel's donations following the seizure of the Peverel family estates by the crown, during the reign of King Henry II. King Henry granted the Peverel families lands within the Peak District to his son, John Count of Mortain (the future King John of England). On his ascendancy to the throne, John transferred this property to the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield and in turn it passed to the Dean and Chapter of Lichfield Cathedral. This transfer started approximately 300 years of disagreement between the Priory and Cathedral about who was rightful owner of the property. Litigation continued throughout this period, including suits in the Vatican Court on several occasions.[1]

This disagreement became violent when in 1250-1, the monks of Lenton Priory armed themselves and attempted to steal wool and lambs from the disputed parish of Tideswell, Derbyshire, which Lichfield controlled. Preempting the monk's attack the Dean of the cathedral ordered the wool and sheep to be kept within the nave of the village church, however the monks of Lenton did not honour the church's sanctuary rights and broke into the building. A fight ensued and 18 lambs were killed within the church, either trampled under the horses' hooves or butchered by the attackers weapons. The monks managed to carry off 14 of the lambs.[1]

In another similar attack around the same time, the monks used violence to steal geese, hay and oats. These attacks caused the Bishop of Lichfield to appeal again to the Pope. Pope Innocent IV assembled a commission which met in 1252 at St. Mary's Church in Leicester. The commission included The warden of the Franciscans of Leicester, the Archdeacon of Chester, and the Prior of the Dominicans of London. The commission ruled Lenton Priory should be fined 100 marks on top of the £60 they had already paid Lichfield Cathedral in "compensation for the damage". The commission attempted to prevent further violent outbreaks by allotting the priory a portion of the tithes from some of the disputed parishes. This, however, provided less than 25 years of peace, as the dispute was reignited in 1275 and was "frequently renewed up to the time of the dissolution of the religious houses".[1]

13th and 14th centuries

In 1228 the priory church tower collapsed. The following year King Henry III granted the monks quarry rights in the Royal Nottingham Forest so that they could get stone to rebuild the tower. Henry III made numerous other donations to the priory to allow further building and restoration including: oak to make roofing shingle for the monk's domatory, (in 1232) thirty Sherwood oaks to build the priory church, and (in 1249) a royal licence to quarry stone from Sherwood forest to construct the priory church.[1]

The majority of the monks at Lenton came from France. Not used to the colder climate in England, in the winter of 1257/58, Pope Alexander IV had to give permission for the monks to wear caps during church services due to the "vehement cold".[1]

By 1262 the priory was considerably in debt. The priory's accounts were inspected by Henry, Prior of Bermondsey, and John, Prior of the French house of Gassicourt, on behalf of the Abbot of Cluny Abbey. Their inspection reveal the priory was home twenty-two monks and that the priory was around £1,000 (£909,512 as of 2015) [3] in debt. This amount was a substantial: around three times the priory's gross annual income, as demonstrated by the 1291 tax records of Pope Nicholas IV, which record the priory as having an annual income of only £339 1s. 2½d.[1] (£244,671 as of 2015) [3].

As an alien priory, owing allegiance to a mother-house in France, during war with France the priory's income was seized by the Crown. This happened repeatedly in the 14th century,[1] until, in 1392, the priory was removed from its mother-houses' control (made denizen).[4]

The priory is believed to have had the finest set of guest-chambers around Nottingham, and as such the priory received a number of royal visits, including: Henry III in 1230, Edward I in 1302 and 1303, Edward II in 1307 and 1323, and Edward III in 1336.[1]

The priory had not solved its debt problems by the beginning of the 14th century. By May 1313 the priory was noted for "its poverty and indebtedness". King Edward II placed the priory under his protection and appointed a keeper to oversee the priory's affairs.[1]

Lenton Priory had previously controlled the Chapel of Saint James (located on St James Street, Central Nottingham). However in 1316, whilst visiting Clipston, Nottinghamshire, King Edward II took the chapel from Lenton and gave it to the Nottingham Whitefriars, whom he was very fond of.[5]

Dissolution

The Valor Ecclesiasticus of 1534 records the priory as having a gross income of £387 10s. 10½d., as well as having "considerable" outgoings.[1]

Lenton's last prior was Nicholas Heath (or Hethe). He was appointed in 1535, having gained the position due to his connection to Thomas Cromwell. Numerous letters to Cromwell exist, from Heath's time as prior.[1]

Prior Heath was thrown into prison in February 1538, along with many of his monks. They were accused of high treason, most likely under the Verbal Treasons Act of December 1534. In March, the prior with eight of his monks (Ralph Swenson, Richard Bower, Richard Atkinson, Christopher Browne, John Trewruan, John Adelenton, William Berry, and William Gylham) and four labourers of Lenton were indicted for treason and executed. Cromwell's private notes reveal Heath's fate (to be executed) was sealed before he had gone to trial.[1]

The prior and monk Ralph Swenson were executed first. Monk William Gylham and the four labourers were sentenced to be hung, drawn an quartered. The executions took place in Nottingham (thought to have been in the market place) and its surroundings, including in front of the priory itself. Some of the quarters of those executed were displayed outside the priory.[1]

The priory was dissolved in 1538.[4] As the monks and prior had been executed, none were given a pension; Unusually none of the servants of the priory were given a pension either, and the five paupers who lived within the priory were thrown out onto the streets, "penniless".[1]

Priors of Lenton[6]

|

|

Lenton Fair

The second royal charter King Henry II granted the priory gave the monks permission to hold an eight-day fair starting on The Feast of Saint Martin: 11 November. In 1232, King Henry III's charter extended the length of the fair to twelve days.[1]

The fair provided a large proportion of the priory's annual income: in 1387 providing £35 of the priory's £300 annual income.[1]

The fair caused numerous disputes with the mayor and burgesses of the town of Nottingham.[1]

The town and priory reached an agreement around 1300 where by no markets were to be held within Nottingham during the period in the Lenton fair. In return the people of Nottingham were given special rates to hire booths at the Lenton fair and were freed from their tolls to Lenton Priory during the time of the fair. Each booth measured 8ft by 8ft.[1]

| Trade | Booth Hire Price |

|---|---|

| Apothecaries, Cloth merchants, Mercers, Pilchers (makers of fur garments) | 12d. |

| Those selling blacks (Blakkes) and ordinary cloths | 8d. |

| Those selling iron (with extra ground available to hire for 2d.) | 4d. |

The Fair continued after the demise of the Priory, though its length was gradually reduced. Its emphasis slowly changed, and in 1584 it was described as a horse-fair when servants of Mary, Queen of Scots attended.[8] By the 17th century the Fair had acquired a reputation as a great fair for all sorts of horses. In the 19th century it was largely frequented by farmers and horse dealers. The Fair finally ceased at the beginning of the 20th century.

History following dissolution

The monastery's lands passed between numerous different owners after the dissolution.[1]

The area was bought by William Stretton in 1802 and he built a large house called "The Priory". William was interested in antiquities and he is known to have removed old architectural materials whilst his house was being constructed. The funds for the house may well have come from the buildings that he and his father built in the Nottingham area. When William died he left the house to his son Sempronius. Colonel Sempronius Stretton died in 1842 and left the house to his brother Severus William Lynam Stretton. Neither of the sons regarded the Priory as home and Severus sold the house. It was bought by the Sisters of Nazareth in 1880.[9] The Sisters of Nazareth sold the property in the early years of the twenty-first century, and the site was redeveloped for housing.

Remains of Lenton Priory today

- Priory Church of St. Anthony, Lenton is thought to incorporate elements of the chapel of the monastic hospital.[4]

- Fragment of stone column where Old Church Street meets Priory Street

- The 12th-century font survives in Holy Trinity Church, Lenton.

- Floor tiles in Nottingham Castle Museum.

- Stained glass in Nuthall Church.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 Page, William (1910). 'House of Cluniac monks: The priory of Lenton', A History of the County of Nottingham: Volume 2. Victoria County History. pp. 91–100.

- ↑ Memoirs Illustrative of the History and Antiquities of the County and City of York, Communicated to the Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, York, July, 1816, p126, with a General Report of the Proceedings of the Meeting, and Catalogue of the Museum Formed on that Occasion By Royal Archaeological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Royal Archaeological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, accessed 16 September 2008

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2014), "What Were the British Earnings and Prices Then? (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Lenton Priory, English Heritage: PastScape

- ↑ William Page, ed. (1910). 'Friaries: Carmelite friars of Nottingham', A History of the County of Nottingham: Volume 2. Victoria County History. pp. 145–147. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ 'House of Cluniac monks: The priory of Lenton', A History of the County of Nottingham: Volume 2 (1910), pp. 91-100.

- ↑ S. E. Kelly, ‘Elmham, Thomas (b. 1364, d. in or after 1427)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 7 Sept 2008

- ↑ Lodge, Edmund, ed., Illustrations of British History, vol.2 (1791), p.303.

- ↑ The Strettons and ‘The Priory’, Lenton Times, accessed August 2009

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||