Lennard-Jones potential

| Computational physics |

|---|

|

|

Numerical analysis · Simulation |

|

Particle |

|

Scientists |

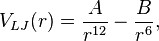

The Lennard-Jones potential (also referred to as the L-J potential, 6-12 potential, or 12-6 potential) is a mathematically simple model that approximates the interaction between a pair of neutral atoms or molecules. A form of this interatomic potential was first proposed in 1924 by John Lennard-Jones.[1] The most common expressions of the L-J potential are

where ε is the depth of the potential well, σ is the finite distance at which the inter-particle potential is zero, r is the distance between the particles, and rm is the distance at which the potential reaches its minimum. At rm, the potential function has the value −ε. The distances are related as rm = 21/6σ (1.122σ). These parameters can be fitted to reproduce experimental data or accurate quantum chemistry calculations. Due to its computational simplicity, the Lennard-Jones potential is used extensively in computer simulations even though more accurate potentials exist.

Explanation

The r−12 term, which is the repulsive term, describes Pauli repulsion at short ranges due to overlapping electron orbitals and the r−6 term, which is the attractive long-range term, describes attraction at long ranges (van der Waals force, or dispersion force).

Differentiating the L-J potential with respect to 'r' gives an expression for the net inter-molecular force between 2 molecules. This inter-molecular force may be attractive or repulsive, depending on the value of 'r'. When 'r' is very small, the 2 molecules repel each other.

Whereas the functional form of the attractive term has a clear physical justification, the repulsive term has no theoretical justification. It is used because it approximates the Pauli repulsion well, and is more convenient due to the relative computational efficiency of calculating r12 as the square of r6.

The Lennard-Jones (12,6) potential can be further approximated by the (exp-6) potential later proposed by R. A. Buckingham, in which the repulsive part is exponential:[2]

The L-J potential is a relatively good approximation and due to its simplicity is often used to describe the properties of gases, and to model dispersion and overlap interactions in molecular models. It is particularly accurate for noble gas atoms and is a good approximation at long and short distances for neutral atoms and molecules.

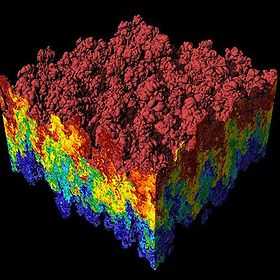

The lowest energy arrangement of an infinite number of atoms described by a Lennard-Jones potential is a hexagonal close-packing. On raising temperature, the lowest free energy arrangement becomes cubic close packing and then liquid. Under pressure the lowest energy structure switches between cubic and hexagonal close packing.[3] Real materials include BCC structures as well.[4]

Other more recent methods, such as the Stockmayer potential, describe the interaction of molecules more accurately. Quantum chemistry methods, Møller–Plesset perturbation theory, coupled cluster method or full configuration interaction can give extremely accurate results, but require large computational cost.

Alternative expressions

There are many different ways of formulating the Lennard-Jones potential The following are some common forms.

AB form

This form is a simplified formulation that is used by some simulation software packages:

where,  and

and  . Conversely,

. Conversely, ![\sigma = \sqrt[6]{\frac{A}{B}}](../I/m/77fb1e2fb4982fb3a613463ea59e69cd.png) and

and  . This is the form in which Lennard-Jones wrote the 12-6 potential.[5]

. This is the form in which Lennard-Jones wrote the 12-6 potential.[5]

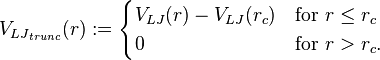

Truncated and shifted Lennard-Jones potential

To save computational time, the Lennard-Jones potential is often truncated at a cut-off distance of rc = 2.5σ, where

![\displaystyle

V_{LJ} ( r_c )

=

V_{LJ} ( 2.5 \sigma )

=

4 \varepsilon

\left[

\left(

\frac

{\sigma}

{2.5 \sigma}

\right)^{12}

-

\left(

\frac

{\sigma}

{2.5 \sigma}

\right)^6

\right]

\approx

-0.0163 \varepsilon](../I/m/ea2feceea8c662a94a2d35fca0fcf083.png)

(1)

i.e., at rc = 2.5σ, the Lennard-Jones potential, VLJ, is about 1/60th of its minimum value, ε (the depth of the potential well).

Beyond

, the truncated potential

is set to zero.

, the truncated potential

is set to zero.

To avoid a jump discontinuity at  , the LJ potential must be shifted upward a little

so that the truncated potential would be zero exactly at the cut-off distance,

, the LJ potential must be shifted upward a little

so that the truncated potential would be zero exactly at the cut-off distance,  .

.

For clarity, let  denote the LJ potential as defined above, i.e.,

denote the LJ potential as defined above, i.e.,

![\displaystyle

V_{LJ}

(r)

=

4 \varepsilon

\left[

\left(

\frac

{\sigma}

{r}

\right)^{12}

-

\left(

\frac

{\sigma}

{r}

\right)^6

\right].](../I/m/55e592337e992dfa2572b340101b7b2d.png)

(2)

Then the truncated Lennard-Jones potential

is defined as follows[6]

is defined as follows[6]

(3)

It can be easily verified that VLJtrunc(rc) = 0, thus eliminating the jump discontinuity at r = rc. Although the value of the (unshifted) Lennard Jones potential at r = rc = 2.5σ is rather small, the effect of the truncation can be significant, for instance on the gas–liquid critical point.[7] Fortunately, the potential energy can be corrected for this effect in a mean field manner by adding so-called tail corrections.[8]

Limitations

- The L-J potential has only two parameters (A and B) which determine the length and energy scales and may, without loss of generality, be set to unity. The potential is therefore unique, and cannot be fitted to properties of any real material.

- With the L-J potential, the number of atoms bonded to an atom does not affect the bond strength. The bond energy per atom therefore increases linearly with the number of bonds per atom. Experiments show instead that the bond energy per atom increases quadratically with the number of bonds .

- Bonding has no directionality: the potential is spherically symmetric.

- The sixth-power term models dipole-dipole interactions due to electron dispersion in noble gases (London dispersion forces), but it does not represent other kinds of bonding well. The twelfth-power term appearing in the potential is chosen for its ease of calculation for simulations (by squaring the sixth-power term) and is not physically based.

- The potential diverges when two atoms approach one another. This may create instabilities that require special treatment in molecular dynamics simulations.

See also

- Morse/Long-range Potential

- Molecular mechanics

- Embedded atom model

- Morse potential

- Force field (chemistry)

- Force field implementation

- Heterogenous catalysis

- Hydrogen spillover

- Physisorption

- Virial expansion

- Lennard-Jones model on SklogWiki.

References

- ↑ Lennard-Jones, J. E. (1924), "On the Determination of Molecular Fields", Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 106 (738): 463–477, Bibcode:1924RSPSA.106..463J, doi:10.1098/rspa.1924.0082.

- ↑ Peter Atkins and Julio de Paula, "Atkins' Physical Chemistry" (8th edn, W. H. Freeman), p.637

- ↑ Barron, T. H. K.; Domb, C. (1955), "On the Cubic and Hexagonal Close-Packed Lattices", Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 227 (1171): 447–465, Bibcode:1955RSPSA.227..447B, doi:10.1098/rspa.1955.0023.

- ↑ Calculation of the Lennard-Jones n–m potential energy parameters for metals. Shu Zhen,G. J. Davies. physica status solidi (a)Volume 78, Issue 2, pages 595–605, 16 August 1983

- ↑ Lennard-Jones, J. E. (1931). "Cohesion". Proceedings of the Physical Society 43 (5): 461. doi:10.1088/0959-5309/43/5/301.

- ↑ softmatter:Lennard-Jones Potential, Soft matter, Materials Digital Library Pathway

- ↑ Smit, B. (1992), "Phase diagrams of Lennard-Jones fluids", Journal of Chemical Physics 96 (11): 8639, Bibcode:1992JChPh..96.8639S, doi:10.1063/1.462271.

- ↑ Frenkel, D. & Smit, B. (2002), Understanding Molecular Simulation (Second ed.), San Diego: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-267351-4.

![V_{LJ} = 4\varepsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right] = \varepsilon \left[ \left(\frac{r_{m}}{r}\right)^{12} - 2\left(\frac{r_{m}}{r}\right)^{6} \right],](../I/m/4b9763cd4defb5082534b13dd7290611.png)

![V_B = \gamma \left[ e^{-r/r_0} - \left( \frac{r_0}{r} \right)^6 \right].](../I/m/4cf9a36b34b8304a5798b0d16895c8c7.png)