Leishu

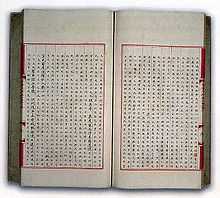

The leishu (Chinese: 類書; literally: "classified books") is a genre of reference books historically compiled in China and other countries of the Sinosphere. The term is generally translated as "encyclopedia", although the leishu are quite different from the modern notion of encyclopedia.[1]

The leishu are composed of sometimes lengthy citations from other works,[2] and often contain copies of entire works, not just excerpts.[3] The works are classified by a systematic set of categories, which are further divided into subcategories.[2] Leishu may be considered anthologies, but are encyclopedic in the sense that they may comprise the entire realm of knowledge at the time of compilation.[2]

Approximately 600 leishu were compiled from the early third century until the eighteenth century, of which 200 have survived.[4] The largest leishu ever compiled was the 1408 Yongle Dadian, containing 370 million Chinese characters,[3] and the largest ever printed was the Gujin Tushu Jicheng, containing 100 million characters and 852,408 pages.[5]

History

The genre first appeared in the early third century. The earliest known leishu or Chinese encyclopaedia was the Huang Lan ("Emperor's mirror"[6]). Sponsored by the emperor of Cao Wei, it was compiled around 220, but has since been lost.[2] However, the term leishu was not used until the Song dynasty (960–1279).[1]

In the later imperial China (Ming and Qing dynasties), emperors sponsored monumental projects to compile all known human knowledge into a single leishu, in which entire works, rather than excerpts, were copied and classified by category.[3] The largest leishu ever compiled, on the order of the Yongle Emperor of Ming, was the Yongle Dadian containing a total of 370 million Chinese characters. The project involved 2,169 scholars, who worked for four years under general editor Yao Guangxiao. It was completed in 1408, but never printed, as the imperial treasury had run out of money.[3]

The Qinding Gujin Tushu Jicheng (Imperially approved synthesis of books and illustrations past and present) is by far the largest leishu ever printed, containing 100 million characters and 852,408 pages.[5] It was compiled by a team of scholars led by Chen Menglei, and printed between 1726 and 1728, during the Qing dynasty.[5]

The riyong leishu (encyclopedias for daily use), containing practical information for people who were literate but below the Confucian elite, were also compiled in the later imperial era. Today, they provide scholars valuable information on non-elite culture and attitudes.[7]

According to Jean-Pierre Diény, the Jiaqing reign (1796–1820) of the Qing dynasty saw the end of the publication of leishu.[8]

In other countries

Other countries of the Sinosphere also adopted the genre of leishu. In 1712, the Sancai Tuhui, a richly illustrated leishu compiled by Ming scholar Wang Qi (王圻) in the early 17th century, was printed in Japan as Wakan Sansai Zue. The Japanese version was edited by Terajima Ryōan (寺島良安), a physician born in Osaka.[8]

Importance

The leishu have played an important role in the preservation of ancient works, many of which have been lost, only preserved completely or partially as part of a leishu compilation. The 7th-century Yiwen Leiju is especially valuable. It contains excerpts from 1,400 pre-7th century works, 90% of which have been otherwise lost. Even though the Yongle Dadian is largely lost, the remnants still contain 385 complete books that have been otherwise lost.[7] The leishu also provide a unique view of the transmission of knowledge and education, and an easy way to locate traditional materials on any given subject.[7]

Major compilations

Approximately 600 leishu were compiled, from the Cao Wei period (early third century) until the 18th century, of which 200 have survived. Among the most important, in chronological order, are:[9]

- Yiwen Leiju (Collection of literature arranged by categories), compiled by Ouyang Xun

- Beitang Shuchao (Excerpts from books in the Northern Hall), compiled by Yu Shinan ca. 630

- Chuxue Ji (Writings for elementary instruction), compiled by Xu Jian et al. between 713 and 742

- Taiping Yulan (Imperially reviewed encyclopaedia of the Taiping era), compiled by Li Fang et al., published 984

- Cefu Yuangui (Outstanding models from the storehouse of literature), compiled by Wang Qinruo et al., completed in 1013

- Yuhai (Ocean of jade), compiled by Wang Yinglin 1330–40

- Yongle Dadian, completed 1408, the largest leishu ever compiled

- Qinding Gujin Tushu Jicheng, 1726–28, the largest leishu ever printed

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lehner 2011, p. 46.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Zurndorfer 2013, p. 505.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Wilkinson 2000, p. 604.

- ↑ Wilkinson 2000, p. 603.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Wilkinson 2000, p. 605.

- ↑ Compare the later "speculum literature" in the Western tradition.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Wilkinson 2000, p. 602.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lehner 2011, p. 47.

- ↑ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 603–5.

Bibliography

- Lehner, Georg (2011). China in European Encyclopaedias, 1700–1850. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-20150-5.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2000). Chinese History: A Manual. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4.

- Zurndorfer, Harriet T. (2013). "Fifteen hundred years of the Chinese encyclopaedia". Encyclopaedism from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-47089-7.