Leicester's Commonwealth

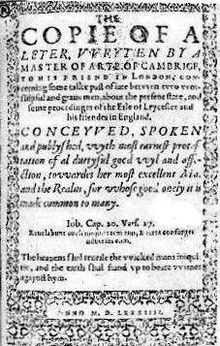

Leicester's Commonwealth (originally titled The Copie of a Leter wryten by a Master of Arts of Cambrige) (1584) is a scurrilous tract that circulated in Elizabethan England and which attacked Queen Elizabeth I's favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. The work was read as Roman Catholic propaganda against the political and religious policy of Elizabeth I's regime, in particular the Puritan sympathies fostered by Leicester. In doing so it portrayed Leicester as an amoral opportunist of "almost satanic malevolence",[1] and circulated lurid stories of his scandalous deeds and his dangerous plots.

The text is presented as "a letter written by a Master of Art of Cambridge to his friend in London, concerning some talk passed of late between two worshipful and grave men about the present state and some proceedings of the Earl of Leicester and his friends in England." The title "Leicester's Commonwealth" was first used in the 1641 edition. The book seriously influenced Leicester's historical reputation in the ensuing centuries.

Content

The book takes the form of a dialogue between a Cambridge scholar, a lawyer, and a gentleman; it begins as a plea for religious toleration, by asserting that Catholics who are loyal to the queen and country should be free to profess their religion. The lawyer, who professes to be a moderate "papist", expresses the view that religious differences do not undermine the patriotism of citizens, giving examples of religiously divided populations who have united to defend their country against external enemies.

The text quickly veers into an attack on the Earl of Leicester, making all kinds of accusations against him, most notably a number of murders. His first is that of his wife Amy Robsart, who according to the tract was found at the bottom of a short flight of stairs with a broken neck, her headdress still standing undisturbed "upon her head".[2] Leicester's hired assassin later confesses while on his death-bed, as "all the devils in hell" tear him in pieces. Meanwhile the assassin's servant, who witnessed the deed, has already been dispatched in prison by Leicester's agents before he could tell the story. With the expert help of his Italian physician, Dr. Giulio, Leicester goes on to remove the husbands of his lovers Douglas, Lady Sheffield and Lettice, Countess of Essex (ladies referred to as "his Old and his New Testaments"[3]). The Cardinal of Chatillon, Nicholas Throckmorton, Lady Margaret Lennox, and the Earl of Sussex are dispatched in the same manner, by poison.[4] After the murder of Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, Leicester pays Francis Drake to kill Thomas Doughty, who knows too much about it (Doughty had been executed by Drake for mutiny at sea).

The work also reveals Leicester's monstrous sexual appetite and his and his new wife's lewd private lives, including abortions, illnesses, and other shortcomings.[5] The death of their little son, which occurred shortly before the book's publication, is commented on with a biblical allusion in a stop press marginal note: "The children of adulterers shall be consumed, and the seed of a wicked bed shall be rooted out."[6]

A born traitor in the third generation who has "nothing of his own, either of his ancestors, or of himself",[6] Leicester is also accused of systematically despoiling the lands the queen has granted him, and of ruthlessly extorting money from those unluckily enough to be in his power. The mathematician Thomas Allen is said to be employing the art of "figuring" to further the earl's unlawful designs and of having endeavoured to bring about a match between his patron and Queen Elizabeth by the black art. Leicester, a "perpetuall dictator"[7] who hates and terrorizes the helpless queen, is to blame that England has no heir of Elizabeth's body since he has prevented her marriage to a foreign prince. This he did by falsely claiming to be engaged to her and showing her suitors' ambassadors "a most disloyal proof" thereof.[8] Having failed to attain the supreme power through marriage, he—who is of no religion himself—is building up a party of misled Puritans that will assist him to dethrone Elizabeth in favour of his brother-in-law, the Earl of Huntingdon. On achieving this, he will get rid of Huntingdon and place the crown on his own head.[9] Leicester's immediate arrest and execution is recommended as the most beneficial act the queen could ever do to her country.[10]

As the book progresses, it increasingly becomes a defense of Mary Stuart's succession rights, which by 1584 had become imperilled due to her involvement in several plots to assassinate Elizabeth.[11]

Authorship

The authorship of the pamphlet has been much disputed. Francis Walsingham, in charge of Elizabeth's secret service, thought Thomas Morgan, the exiled agent of Mary Stuart, to be the author when the book first surfaced in August 1584.[12] Dudley likewise believed that Mary was involved in its conception: "Leicester has lately told a friend that he will persecute you to the uttermost", she was informed by one of her spies.[13] The Jesuit Robert Persons soon became popularly associated with it and it was published under his name in later editions; however he denied authorship in his memoirs, although he was involved in smuggling the book from France to England.[14] Scholars now generally believe that Persons was not the author.[15] Ralph Emerson, a Catholic activist, was arrested in possession of several copies, but could not or would not identify the author when questioned.

Some modern scholars have suggested that there was no single author, and that several members of the exiled Catholic community based in France wrote the text as a group effort; the chief candidates being Charles Arundell and Charles Paget. The original intention of the text is probably linked to a factional struggle at the French court. It favoured the party of the Guises, supporters of the Catholic League, against those with a more positive attitude to Elizabeth and England.[15]

Suppression

The work was welcomed by exiled Catholics as the best weapon they had; Francis Englefield, who served Philip II of Spain, wrote on hearing of it: "Instead of the sword which we cannot obtain, we must fight with prayer and pen." These kinds of books, he thought, "ought to be to this Queen of England's annoyance ... who I hope shall have a fall at last".[16]

Elizabeth's government made considerable efforts to suppress the work, but according to D.C. Peck, "from the evidence of the book's circulation and its later effects, however, the government's attempts at suppression must be said largely to have failed."[17] The queen published an official condemnation of the libel: "Her majesty [testifieth] in her conscience, before God, unto you, that her Highness not only knoweth in assured certainty, the libels and books against the said Earl, to be most malicious, false and slanderous, and such as none but the devil himself could deem to be true".[18] She offered an amnesty for anyone who handed in the book, but threatened imprisonment for anyone who was found with it in their possession.[19] Attempts to identify and suppress printing of it in France were unsuccessful, but imported copies were seized and Elizabeth managed to get King James VI of Scotland to impound copies. Nevertheless hand-copied versions of the book circulated widely.[19]

Sir Philip Sidney wrote a defence of his uncle against the attacks in Leicester's Commonwealth. He dismissed most of the charges as alehouse talk and instead concentrated on defending the noble lineage and character of his grandfather John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland; he even rhetorically challenged the author to a duel. Sidney's reply remained unpublished, though.[20] It was eventually printed in Collins's "Sydney Papers" in 1746.

The book highly influenced Leicester's historical reputation, as later writers from William Camden onwards relied heavily on it. Thus it laid the foundation of a historiographical tradition that depicted the Earl as the classical Machiavellian courtier and as the evil spirit of Elizabeth's court.

Notes

- ↑ Haynes, Alan: The White Bear: The Elizabethan Earl of Leicester, Peter Owen, ISBN 0-7206-0672-1, p. 151

- ↑ Jenkins, Elizabeth (2002): Elizabeth and Leicester, The Phoenix Press, ISBN 1-84212-560-5, pp. 65, 291

- ↑ Jenkins 2002 p. 291

- ↑ Wilson, Derek (1981): Sweet Robin: A Biography of Robert Dudley Earl of Leicester 1533–1588, Hamish Hamilton, ISBN 0-241-10149-2, pp. 255

- ↑ Jenkins 2002 pp. 212, 287, 293, 294; Wilson 1981 p. 255

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Jenkins 2002 p. 294

- ↑ Burgoyne, F.J. (ed.) (1904): History of Queen Elizabeth, Amy Robsart and the Earl of Leicester, being a Reprint of "Leycesters Commonwealth" 1641, Longmans, p. 255

- ↑ Jenkins 2002 p. 202

- ↑ Wilson 1981 pp. 254, 258–259; Burgoyne 1904 p. 20

- ↑ Wilson 1981 pp. 261

- ↑ Wilson 1981 pp. 253–254

- ↑ Jenkins 2002 p. 290

- ↑ Jenkins 2002 p. 298

- ↑ Wilson 1981 pp. 263, 264, 330

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Houliston, Victor. "Persons, Robert". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21474. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Jenkins 2002 p. 296

- ↑ Peck, DC, "Government Suppression of Elizabethan Catholic Books: The Case of Leicester's Commonwealth", The Library Quarterly, 1977 The University of Chicago Press,

- ↑ Wilson p. 262

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Dorothy Auchter, Dictionary of literary and dramatic censorship in Tudor and Stuart England, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, p.199

- ↑ Jenkins 2002 pp. 294–295

External links

Modern edition with critical apparatus: Leicester's Commonwealth: The Copy of a Letter Written by a Master of Art of Cambridge (1584) and Related Documents (ed. by D.C. Peck, Ohio University Press, 1985)