Legitimacy of Queen Victoria

The parentage of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom has been the subject of speculation.

Succession crisis

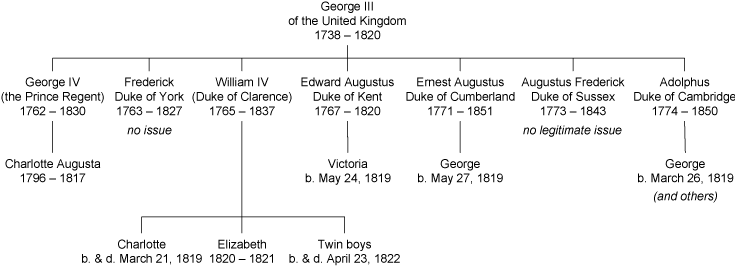

Princess Charlotte of Wales was the only daughter and heir of the Prince Regent (later King George IV). Her death in childbirth in 1817 set off a race between the Prince Regent's brothers, the seven surviving sons of King George III, to see who could father a legitimate heir. Some of the brothers had been previously involved in scandals. Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, the second in line to the throne, was amicably separated from his wife, Princess Frederica Charlotte of Prussia. The sixth son, Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, had contracted two marriages in contravention of the Royal Marriages Act 1772 (as had the Prince Regent before his marriage to Charlotte's mother). Three brothers, the third, fourth and seventh in line to the throne, married in 1818: Prince William, Duke of Clarence; Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn; and Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge. The fifth son, Prince Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, was already married.

The Duke of Clarence married Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. Though he had been able to father ten illegitimate children with an earlier mistress, none of his children by his wife survived childhood. The second daughter, Elizabeth, lived the longest, being born on 10 December 1820 and dying on 4 March 1821. The next son to produce an heir was the Duke of Cambridge, whose son George was born on 26 March 1819. He would be displaced two months later by the birth of a daughter to the Duke of Kent and his wife. Their first and only child was called Princess Alexandrina Victoria but was known to her family as "Drina". She was born on 24 May 1819, just three days before the son of the Duke of Cumberland, also called George.

Both George III and the Duke of Kent died in January 1820. The Prince Regent became George IV and Drina was third in line to the throne after her uncles, the Duke of York and Duke of Clarence (the future William IV). She would ultimately take the throne as Queen Victoria in 1837.

Controversy

Rumours about Victoria's parentage centred on a controversial Irish soldier and adventurer called John Conroy who was her mother's private secretary and the comptroller of her household. The Duchess of Kent was the same age as Conroy, whereas she was nineteen years younger than her husband; the court gossiped openly about their relationship. After the Duke's death Conroy assumed a parental role towards Victoria that she bitterly resented. This caused a near permanent rift between Victoria and her mother, as well as between the Duchess and her brother-in-law, William IV. Conroy expected that when Victoria became queen he would be made her private secretary, but instead one of her first acts as monarch was to dismiss him from her household.

The belief that the Duchess and Conroy were lovers was widespread. When asked by Charles Greville whether he believed they were lovers, the Duke of Wellington replied that he "supposed so".[1] The Duke later recounted a story that when Victoria was young she had caught Conroy and the Duchess engaged in what were diplomatically called "some familiarities".[2][3] Wellington reported that she told Baroness Louise Lehzen, who told her close ally, Madame de Späth, who confronted the Duchess about her behaviour. According to Wellington, the Duchess of Kent was furious and promptly dismissed de Späth.[4] Victoria, when queen, appears to have disputed the story, stating that her mother's piety would have prevented any undue familiarity with Conroy.[5]

Genetics

A. N. Wilson suggested that Victoria's father could not have been the Duke of Kent for two reasons:

- The sudden appearance of hæmophilia in the descendants of Victoria. The illness did not exist in the royal family before.

- The supposed disappearance of porphyria from the descendants of Victoria. According to Wilson, the disease was prevalent in the royal family before Victoria but not afterwards.[6]

Both arguments can be countered. Since hæmophilia is X-linked, in order for a father to transmit the condition he must have it himself, but Conroy was healthy. Hæmophiliacs were unlikely to survive in the early nineteenth-century, given the poor state of medicine at the time.[7] Indeed, life expectancy was 11 years or younger, even into the later half of the twentieth-century,[8] and is still as low in developing countries.[9] Nor is there evidence of hæmophilia in either Conroy's ancestors or descendants, or any mention of any hæmophiliacs in any document associated with the Kents. It is likely that the mutation arose spontaneously because the Duke of Kent was in his 50s when Victoria was conceived; hæmophilia arises more frequently in the children of older fathers,[10] and spontaneous mutations account for about 30% of cases.[11]

With regard to porphyria (which famously George III may have had), there is no genetic evidence that the royal family even had the disease and its diagnosis in George III's case (and others) has been questioned.[12] If the diagnosis of hereditary porphyria is correct, it may have continued among descendants of Victoria. At least two of her descendants, Charlotte, Duchess of Saxe-Meiningen, and Prince William of Gloucester are suspected of having suffered from it.[13]

Notes

- ↑ Hibbert, Christopher (2001). Queen Victoria: A Personal History. De Capo Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-306-81085-5.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 27

- ↑ Longford, Elizabeth (1965). Queen Victoria: Born to Succeed. New York: Pyramid Books. p. 118. ASIN B001Q77XAQ.

- ↑ Williams, Kate (2010). Becoming Queen Victoria: The Tragic Death of Princess Charlotte and the Unexpected Rise of Britain's Greatest Monarch. Ballatine Books. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-345-46195-7.

- ↑ Longford, p. 119

- ↑ A. N. Wilson, The Victorians (Hutchinson, 2002). ISBN 0-09-179421-8, page 25

- ↑ Packard, Jerrold (1973). Victoria's Daughters. New York: St. Martin's Press, pp. 43-44

- ↑ Hemophilia Overview eMedicine from webMD. Dimitrios P Agaliotis, MD, PhD, FACP, Robert A Zaiden, MD, Fellow, and Saduman Ozturk, PA-C. Updated: 24 November 2009.

- ↑ Konkle, Barbara A.; Josephson, Neil C.; Nakaya Fletcher, Shelley M.; Thompson, Arthur R. (September 22, 2011) Hemophilia B, in GeneReviews™ [Internet]. Pagon, R.A.; Adam, M. P.; Bird, T.D., et al., editors. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1993-2013

- ↑ McKusick, Victor A. (1965) "The Royal Hemophilia", Scientific American, vol. 213, p. 91; Jones, Steve (1993) The Language of the Genes, London: HarperCollins, ISBN 0-00-255020-2, p. 69; Jones, Steve (1996) In The Blood: God, Genes and Destiny, London: HarperCollins, ISBN 0-00-255511-5, p. 270; Rushton, Alan R. (2008) Royal Maladies: Inherited Diseases in the Royal Houses of Europe, Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford, ISBN 1-4251-6810-8, pp. 31–32

- ↑ Hemophilia B (Factor IX), National Hemophilia Foundation, 2006, retrieved 20 June 2010

- ↑ Peters, Timothy J.; Wilkinson, D. (2010), "King George III and porphyria: a clinical re-examination of the historical evidence", History of Psychiatry 21 (1): 3–19, doi:10.1177/0957154X09102616, PMID 21877427

- ↑ Röhl, John C. G.; Warren, Martin; Hunt, David (1998) Purple Secret: Genes, "Madness" and the Royal Houses of Europe, London: Bantam Press, ISBN 0-593-04148-8

Further reading

- Katherine Hudson, A Royal Conflict: Sir John Conroy & the Young Victoria (Hodder & Stoughton, 1994)