Legal aspects of transsexualism in the United States

In general, transsexual people have or are seeking to establish a permanent identity as the sex opposite the sex which they were assigned at birth. All jurisdictions in the United States recognize the two biological sexes of male and female and grant certain rights based on those sexes. This raises many legal issues for transsexual people in areas such as legal identification, marriage, and discrimination.

In the United States, classifying a person's sex as male or female is a power which is left to the jurisdiction of the states. As is the case throughout the world, the degree to which a given state recognizes a transsexual person as his or her desired sex varies and is dependent on factors such as the "steps" the person has taken in his or her transition, such as psychological therapy, hormone therapy, and sex reassignment surgery (SRS).

Birth certificates and marriage

2New York City issues its own birth certificates, which also require SRS in order to amend the sex designation.

3Illinois does not require genital reconstruction surgery to amend the sex on birth certificates, but it does require proof of an "operation."

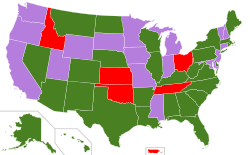

States make their own laws about birth certificates and marriage, and state courts have varied in their application of such laws to transsexual people. Several courts have come to the conclusion that sex reassignments are not recognized for the purpose of marriage, including courts in Illinois, Texas, and New York.[1] A majority of states permit the name and sex to be changed on a birth certificate, either through amending the existing birth certificate or by issuing a new one. Only Idaho, Kansas, Ohio, and Tennessee refuse to change the gender marker on a birth certificate as of April 2015.[2] Texas, by opinion of the local clerk's office, will make necessary changes to a birth certificate (including amendment of sex if a court order is presented).

As of July 2014 New York State passed legislation easing changing recorded gender and as of December 2014 New York City followed, completely eliminating the need for gender reassignment surgery) when filing for birth gender change in New York.

Court cases

In 1959, Christine Jorgensen, a trans woman, was denied a marriage license by a clerk in New York City, on the basis that her birth certificate listed her as male,[3][4] however, Jorgensen did not pursue the matter in court.

The first case to consider transsexualism in the U.S. was Mtr. of Anonymous v. Weiner, 50 Misc. 2d 380, 270 N.Y.S.2d 319 (1966), in which a post-operative transsexual sought from New York City a change of their name and sex on their birth certificate. The New York City Health Department refused to grant the request. The person took the case to court, but the court ruled that granting of the request was not permitted by the New York City Health Code, which only permitted a change of sex on the birth certificate if an error was made recording it at birth.[5][6]

In the case of Matter of Anonymous, 57 Misc. 2d 813, 293 N.Y.S.2d 834 (1968), a similar request was also denied. However, in that case, and in the case of Matter of Anonymous, 64 Misc. 2d 309, 314 N.Y.S.2d 668 (1970), a request was granted for a change of name.

The decision of the court in Weiner was again affirmed in Mtr. of Hartin v. Dir. of Bur. of Recs., 75 Misc. 2d 229, 232, 347 N.Y.S.2d 515 (1973) and Anonymous v. Mellon, 91 Misc. 2d 375, 383, 398 N.Y.S.2d 99 (1977). However, despite this, there can be noted as time progressed an increasing support expressed in judgements by New York courts for permitting changes in birth certificates, even though they still held to do so would require legislative action.

It should be noted that classification of characteristic sex is a public health matter in New York; and New York City has its own health department which operates separately and autonomously from the New York State health department.

Another important case was Darnell v. Lloyd, 395 F. Supp. 1210 (D. Conn. 1975),[7] where the court found that substantial state interest must be demonstrated to justify refusing to grant a change in sex recorded on a birth certificate.

The first case in the United States which found that post-operative transsexual people could marry in their post-operative sex was the New Jersey case M.T. v J.T., 140 N.J. Super. 77, 355 A.2d 204, cert. denied 71 N.J. 345 (1976). Here the court expressly considered the English Corbett v. Corbett decision, but rejected its reasoning.

In K. v. Health Division, 277 Or. 371, 560 P.2d 1070 (1977),[8] the Oregon Supreme Court rejected an application for a change of name or sex on the birth certificate of a post-operative transsexual, on the grounds that there was no legislative authority for such a change to be made.

In Littleton v. Prange, 9 SW3d 223 (1999),[9] Christie Lee Littleton, a post-operative male-to-female transsexual, argued to the Texas 4th Court of Appeals that her marriage to her genetically male husband (deceased) was legally binding and hence she was entitled to his estate. The court decided that plaintiff's gender is equal to her chromosomes, which were XY (male). The court subsequently invalidated her revision to her birth certificate, as well as her Kentucky marriage license, ruling "We hold, as a matter of law, that Christie Littleton is a male. As a male, Christie cannot be married to another male. Her marriage to Jonathon was invalid, and she cannot bring a cause of action as his surviving spouse." Plaintiff appealed to SCOTUS but it denied her Writ of Certiorari on 2000-10-02.

'The Kansas Appealate Court ruling in In re Estate of Gardiner (2001)[10] considers and rejects Littleton, preferring M.T. v. J.T. instead. In this case, the Kansas Appellate Court concludes that "[A] trial court must consider and decide whether an individual was male or female at the time the individual's marriage license was issued and the individual was married, not simply what the individual's chromosomes were or were not at the moment of birth. The court may use chromosome makeup as one factor, but not the exclusive factor, in arriving at a decision. Aside from chromosomes, we adopt the criteria set forth by Professor Greenberg. On remand, the trial court is directed to consider factors in addition to chromosome makeup, including: gonadal sex, internal morphologic sex, external morphologic sex, hormonal sex, phenotypic sex, assigned sex and gender of rearing, and sexual identity." In 2002, the Kansas Supreme Court reversed the Appellate court decision in part, following Littleton.

The custody case of trans man Michael Kantaras made national news.[11]

In re Jose Mauricio LOVO-Lara, 23 I&N Dec. 746 (BIA 2005),[12] the (Federal) US Dept. of Justice, Board of Immigration Appeals ruled that for purposes of an immigration visa: "A marriage between a postoperative transsexual and a person of the opposite sex may be the basis for benefits under ..., where the State in which the marriage occurred recognizes the change in sex of the postoperative transsexual and considers the marriage a valid heterosexual marriage."

On April 22, 2013 case 13AR-CV00157 was heard before the Missouri courts on the matter of a transgender name change with amendments - the accompanying amendments dealt with an explicit granting of the petitioner the right to change gender with the Missouri Department of Revenue and other venues pertaining to the use of state identification.[13] On May 20, 2013 case 13AR-CV00240 was heard before the Missouri courts, with a partial delay, on the matter of gender affirmation and recognition for Jamie Miranda Glistenburg.[14] Although Mo. Ann. Stat. § 193.215(9) was not completely invalidated via court orders 13AR-CV00157 and 13AR-CV00240, the orders effectively silenced the discriminatory law until repealed by order of a federal court or by legislative action. The ruling in 13AR-CV00240 that silences Mo. Ann. Stat. § 193.215(9) reads, in brief, as follows, "...it is found that said request of relief is proper and that such change will not be detrimental to the interest of any persons, nor be against the interest of the state or of any given establishment ... Wherefore, the court understands that select circumstances, such as this case, require judicial intervention in order to prevent discrimination. Moreover, the explicit requirement of surgical procedures or medications that may be deemed unsuitable, dangerous, or unnecessary to the Petitioner by medical assertion shall be given relief notwithstanding Mo. Ann. Stat. § 193.215(9)..." Because of the judicial precedent established in the case of 13AR-CV00240 there are many transgender individuals and lawyers seeking similar relief in other restrictive states.[15]

Drivers' licenses

All U.S. states allow the gender marker to be changed on a driver's license,[16] although the requirements for doing so vary by state. Often, the requirements for changing one's driver's license are less stringent than those for changing the marker on the birth certificate. For example, the state of Massachusetts requires SRS for a birth certificate change,[17] but only a form including a sworn statement from a physician that the applicant is in fact the new gender to correct the sex designation on a driver's license.[18] The state of Virginia has policies similar to those of Massachusetts, requiring SRS for a birth certificate change, but not for a driver's license change.[19][20]

Sometimes, the states' requirements and laws conflict with and are dependent on each other; for example, a transsexual woman who was born in Ohio but living in Kentucky will be unable to have the gender marker changed on her Kentucky driver's license. This is due to the fact that Kentucky requires an amended birth certificate reflecting the new gender, but the state of Ohio does not change gender markers on birth certificates.[21]

Passports

The State Department determines what identifying biographical information is placed on passports. On June 10, 2010, the policy on gender changes was amended to allow permanent gender marker changes to be made with the statement of a physician that "the applicant has had appropriate clinical treatment for gender transition to the new gender."[22] The previous policy required a statement from a surgeon that gender reassignment surgery was completed.[23]

Employment discrimination

Laws

Although the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides equal protection under the law for all, there is no federal law designating transgender as a protected class, or specifically requiring equal treatment for transgender people. An attempt was made to add such language to ENDA, but it was unsuccessful.

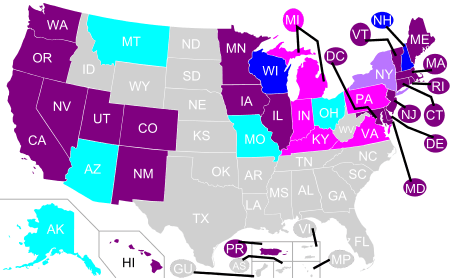

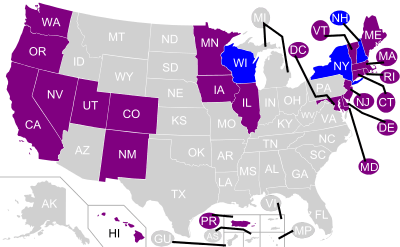

There are 19 states and over 225 jurisdictions (as of 28 January 2015[24]) including the District of Columbia which feature legislation that prohibit discrimination based on gender identity in either employment, housing, and/or public accommodations. This legislation is similar to protections against sex and racial discrimination.

| State | Date begun | Employment | Housing | Public accommodations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minnesota | 1993 | |

|

|

| Rhode Island | 1995 (public accommodation) July 17, 2001 (employment and housing)[25] |

|

|

|

| New Mexico | 2003 (employment and housing) 2004 (public accommodation) |

|

|

|

| California[26] | August 2, 2003 (employment and housing) October 10, 2011 (public accommodations) |

|

|

|

| District of Columbia | 2005 (employment and housing) 2006 (public accommodations) |

|

|

|

| Maine | 2005 | |

|

|

| Illinois | 2005 (employment and housing) 2006 (public accommodations) |

|

|

|

| Hawaii | 2005 (housing and public accommodations) 2011 (employment) |

|

|

|

| Washington | January 2006 | |

|

|

| New Jersey | 2006 | |

|

|

| Vermont | 2007 | |

|

|

| Oregon | 2007 | |

|

|

| Iowa | 2007 | |

|

|

| Colorado[27] | 2007 (employment and housing) 2008 (public accommodations) |

|

|

|

| Nevada | 2011 | |

|

|

| Connecticut[28] | 2011 | |

|

|

| Massachusetts | 2011 | |

|

|

| Delaware | 2013 | |

|

|

| Maryland | 2014 | |

|

|

| Utah | 2015 | |

|

|

On November 16, 2011, House Bill 3810 was passed in Massachusetts.[29] This bill covers discrimination based on gender identity, but not gender expression, and has no provisions for public accommodation.

On January 30, 2012, HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan announced new regulations that would require all housing providers that receive HUD funding to prevent housing discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.[30] These regulations went into effect on March 5, 2012.[31]

Cases

In 2000, a court ruling in Connecticut determined that conventional sex discrimination laws protected transgender persons. However, in 2011, to clarify and codify this ruling, a separate law was passed defining legal anti-discrimination protections on the basis of gender identity.[32]

On October 16, 1976, a Supreme Court rejected plaintiff's appeal in sex discrimination case involving termination from teaching job after sex-change operation from a New Jersey school system.[33]

Carroll v. Talman Fed. Savs. & Loan Association, 604 F.2d 1028, 1032 (7th Cir.) 1979, held that dress codes are permissible. "So long as [dress codes] and some justification in commonly accepted social norms and are reasonably related to the employer’s business needs, such regulations are not necessarily violations of Title VII even though the standards prescribed differ somewhat for men and women.”[34]

In Ulane v. Eastern Airlines Inc. 742 F.2d 1081 (7th Cir. 1984) Karen Ulane, a pilot who was assigned male at birth, underwent sex reassignment surgery to attain typically female characteristics. The Seventh Circuit denied Title VII sex discrimination protection by narrowly interpreting "sex" discrimination as discrimination “against women" [and denying Ulane's womanhood].[35]

The case of Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins 490 U.S. 228 (1989), expanded the protection of Title VII by prohibiting gender discrimination, which includes sex stereotyping. In that case, a woman who was discriminated against by her employer for being too “masculine" was granted Title VII relief.[36]

Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc. 523 U.S. 75 (1998), found that same-sex sexual harassment is actionable under Title VII.[37]

A gender stereotype is an assumption about how a person should dress which could encompass a significant range of transgender behavior. This potentially significant change in the law was not tested until Smith v. City of Salem 378 F.3d 566, 568 (6th Cir. 2004). Smith, a male to female transsexual, had been employed as a lieutenant in the fire department without incident for seven years. After doctors diagnosed Smith with Gender Identity Disorder (“GID”), she began to experience harassment and retaliation following complaint. She filed Title VII claims of sex discrimination and retaliation, equal protection and due process claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, and state law claims of invasion of privacy and civil conspiracy. On appeal, the Price Waterhouse precedent was applied at p574: “[i]t follows that employers who discriminate against men because they do wear dresses and makeup, or otherwise act femininely, are also engaging in sex discrimination, because the discrimination would not occur but for the victim’s sex.”[38] Chow (2005 at p214) comments that the Sixth Circuit’s holding and reasoning represents a significant victory for transgender people. By reiterating that discrimination based on both sex and gender expression is forbidden under Title VII, the court steers transgender jurisprudence in a more expansive direction. But dress codes, which frequently have separate rules based solely on gender, continue. Carroll v. Talman Fed. Savs. & Loan Association, 604 F.2d 1028, 1032 (7th Cir.) 1979, has not been overruled.

Harrah's implemented a policy named "Personal Best", in which it dictated a general dress code for its male and female employees. Females were required to wear makeup, and there were similar rules for males. One female employee, Darlene Jesperson, objected and sued under Title VII. In Jespersen v. Harrah's Operating Co., No. 03-15045 (9th Cir. Apr 14, 2006), plaintiff conceded that dress codes could be legitimate but that certain aspects could nevertheless be demeaning; plaintiff also cited Price Waterhouse. The Ninth Circuit disagreed, upholding the practice of business-related gender-specific dress codes. When such a dress code is in force, an employee amid transition could find it impossible to obey the rules.

In Glenn v. Brumby, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals held that the Equal Protection Clause prevented the state of Georgia from discriminating against an employee on the grounds of transsexual status.[39][40]

Prisoner's rights

In September 2011, a California state court denied the request of a California inmate, Lyralisa Stevens, for sex reassignment surgery at the state's expense.[41]

On January 17, 2014, in Kosilek v. Spencer a three-judge panel of the First Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the Massachusetts Department of Corrections to provide Michelle Kosilek, a Massachusetts inmate, with sex reassignment surgery. It said denying the surgery violated Kosilek's Eighth Amendment rights included "receiving medically necessary treatment ... even if that treatment strikes some as odd or unorthodox".[42]

On April 3, 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice intervened in a federal lawsuit filed in Georgia to argue that denying hormone treatment for transgender inmates violates their rights. It contended that the state's policy that only allows for continuing treatments begun before incarceration was insufficient and that inmate treatment needs to be based on ongoing assessments.[43] The case was brought by Ashley Diamond, an inmate who had used hormone treatment for seventeen years before entering the Georgia prison system.[44]

Taxes

IRS Publication 502[45] lists medical expenses that are tax-deductible to the extent they 1) exceed 7.5% of the individual's adjusted gross income, and 2) were not paid for by any insurance or other third party. For example, a person with $20,000 gross adjusted income can deduct all medical expenses after the first $1,500 spent. If that person incurred $16,000 in medical expenses during the tax year, then $14,500 is deductible. At higher incomes where the 7.5% floor becomes substantial, the deductible amount is often less than the standard deduction, in which case it is not cost-effective to claim.

Included in IRS Publication 502 are several deductions that may apply to gender transition treatments:

- Hospital services if staying for medical treatment;

- Laboratory fees;

- Legal fees;

- Lodging during treatments;

- Meals taken during treatments;

- Medicines, which could include HRT;

- Operations if they are "legal operations that are not for unnecessary cosmetic surgery";

- Psychoanalysis;

- Psychologist;

- Sterilization, which could include orchiectomy;

- Therapy;

- Transportation; and

- X-ray.

The deduction for operations was denied to a transsexual woman but was restored in tax court.[46] The deductibility of the other items in Publication 502 was never in dispute.

Immigration

In 2000, the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that "gay men with female sexual identities [sic] in Mexico constitute a 'particular social group'" that was persecuted and was entitled to asylum in the US (Hernandez-Montiel v. INS).[47][48] Since then, several cases have reinforced and clarified the decision.[49] Morales v. Gonzales (2007) is the only published decision in asylum law that uses "male-to-female transsexual" instead of "gay man with female sexual identity".[49] An immigration judge stated that, under Hernandez-Montiel, Morales would have been eligible for asylum (if not for her criminal conviction).[50]

Critics have argued that allowing transgender people to apply for asylum "would invite a flood of people who could claim a 'well-founded fear' of persecution".[48] Precise numbers are unknown, but Immigration Equality, a nonprofit for LGBT immigrants, estimates hundreds of cases.[48]

See also

- Transgender disenfranchisement in the United States

- Legal aspects of transsexualism

- Transgender American history

- Name change

- List of transgender-related topics

- Changing legal gender assignment in Brazil

- Changing legal gender assignment in Canada

References

- Chow, Melinda. (2005). "Smith v. City of Salem: Transgendered Jurisprudence and an Expanding Meaning of Sex Discrimination under Title VII". Harvard Journal of Law & Gender. Vol. 28. Winter. 207.

- NYC Council eases requirements for transgender people to change ID, December 8, 2014* New York State Modernizes Policy Around Gender Markers on Birth Certificates, June 5, 2014

Notes

- ↑ http://writ.news.findlaw.com/grossman/20050308.html Grenberg, Julie (2006). "The Roads Less Travelled: The Problem with Binary Sex Categories". In Currah, Paisley; Juang, Richard; Minter, Minter. Transgender Rights. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press. pp. 51–73. ISBN 0-8166-4312-1.

- ↑ http://www.lambdalegal.org/publications/changing-birth-certificate-sex-designations-state-by-state-guidelines

- ↑ Staff report (April 4, 1959). Bars Marriage Permit; Clerk Rejects Proof of Sex of Christine Jorgensen (subscription required). New York Times

- ↑ "Christine Denied Marriage License". Toledo Blade. April 4, 1959. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ↑ Turkington, Richard C.; Allen, Anita L. (August 2002). Privacy law: cases and materials. West Group. pp. 861–. ISBN 9780314262042. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ↑ Markowitz, Stephanie. "CHANGE OF SEX DESIGNATION ON TRANSSEXUALS’ BIRTH CERTIFICATES: PUBLIC POLICY AND EQUAL PROTECTION". CARDOZO JOURNAL OF LAW & GENDER 14: 705–.

- ↑ "Diana M. DARNELL v. Douglas LLOYD, Commissioner of Health, State of Connecticut.". Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ↑ "Annotations to ORS Chapter 432". Oregon State Legislature. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ↑ "Case # 04-99-00010-CV". Texas Fourth Court of Appeals. 2000. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ↑ "85030 -- In re Estate of Gardiner". Court of Appeals of the State of Kansas. 2000. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ↑ Canedy, Dana (February 18, 2002). Sex Change Complicates Battle Over Child Custody. New York Times

- ↑ re Jose Mauricio LOVO-Lara, 23 I&N Dec. 746 (BIA 2005)

- ↑ http://transascity.org/files/Glistenburg_Name_Change_Real_Example.pdf

- ↑ http://transascity.org/files/Glistenburg_Gender_Change_Real_Example.pdf

- ↑ http://transascity.org/missouri-transition-information/

- ↑ "Driver's License Policies by State". National Center for Transgender Equality. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "General Laws". Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Change of Gender". Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Sources of Authority to Amend Sex Designation on Birth Certificates". Lambda Legal. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Gender Change Request". Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Driver's License Policies by State". National Center for Transgender Equality. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ↑ "7 FAM 1300 APPENDIX M - GENDER CHANGE". United States Department of State. June 10, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ↑ "7 FAM 1300 APPENDIX F - PASSPORT AMENDMENTS". United States Department of State. March 18, 2009. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ↑ Cities and Counties with Non-Discrimination Ordinances that Include Gender Identity

- ↑ Transgender Law and Policy: Rhode Island News Release

- ↑ Cal Civ Code sec. 51

- ↑ C.R.S. 24-34-402 (2008)

- ↑ HB-6599 An Act Concerning Discrimination (2011)

- ↑ HB3810, "An act relative to gender identity"

- ↑ "HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan announces new regulations to ensure equal access to housing for all Americans regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity" (Press release). United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. January 30, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ↑ "Equal Access to Housing in HUD Programs Regardless of Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity". Federal Register. February 3, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ↑ Declaratory Ruling on Behalf of John/Jane Doe (Connecticut Human Rights Commission 2000)

- ↑ Supreme Court / Sex Discrimination Case / New Jersey Teacher NBC News broadcast from the Vanderbilt Television News Archive

- ↑ "Ca 79-3151 Carroll v. Talman Federal Savings and Loan Association of Chicago". United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Ulane v. Eastern Airlines, Inc., 742 F. 2d 1081 - Court of Appeals, 7th Circuit 1984". United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins". American Psychological Association. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ Minter, Shannon (2003). "Representing Transsexual Clients: Selected Legal Issues". National Center for Lesbian Rights. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ↑ "SMITH v. CITY OF SALEM OHIO". United States Court of Appeals,Sixth Circuit. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ "VIDEO: Eleventh Circuit upholds victory for transgender employee fired by Georgia Legislature". San Diego Gay & Lesbian News. December 6, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ↑ Dyana Bagby (December 9, 2011). "Vandy Beth Glenn may soon return to work at Ga. General Assembly". The GA Voice. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ↑ Dolan, Jack (September 22, 2011). "Inmate loses bid for taxpayer-paid sex-change operation". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Finucane, Martin; Ellement, John R.; Valencia, Milton J. (January 17, 2014). "Mass. appeals court upholds inmate's right to taxpayer-funded sex change surgery". Boston Globe. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ↑ Apuzzo, Matt (April 3, 2015). "Transgender Inmate's Hormone Treatment Lawsuit Gets Justice Dept. Backing". New York Times. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ↑ Sontag, Deborah (April 5, 2015). "Transgender Woman Cites Attacks and Abuse in Men's Prison". New York Times. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Publication 502 (2008), Medical and Dental Expenses". Internal Revenue Service. 2009. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ↑ O’Donnabhain v. Commissioner, 134 T.C. No. 4 (February 2, 2010)

- ↑ Hernandez-Montiel v. INS, 225 F.3d 1084 (9th Cir. 2000).

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Smiley, Lauren (November 26, 2008). "Border Crossers". SF Weekly. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Immigration Law and the Transgender Client: Chapter Five §§5.5.1.1–4

- ↑ Morales v. Gonzales, 478 F.3d 972, 977 (9th Cir. 2007).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||