Law of the iterated logarithm

(red), its variance

(red), its variance  given by CLT (blue) and its bound

given by CLT (blue) and its bound  given by LIL (green). Notice the way it randomly switches from the upper bound given by the law of large numbers to the lower bound. Both axes are non-linearly transformed (as explained in figure summary) to make this effect more visible .

given by LIL (green). Notice the way it randomly switches from the upper bound given by the law of large numbers to the lower bound. Both axes are non-linearly transformed (as explained in figure summary) to make this effect more visible .In probability theory, the law of the iterated logarithm describes the magnitude of the fluctuations of a random walk. The original statement of the law of the iterated logarithm is due to A. Y. Khinchin (1924).[1] Another statement was given by A.N. Kolmogorov in 1929.[2]

Statement

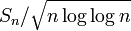

Let {Yn} be independent, identically distributed random variables with means zero and unit variances. Let Sn = Y1 + … + Yn. Then

where “log” is the natural logarithm, “lim sup” denotes the limit superior, and “a.s.” stands for “almost surely”.[3] [4]

Discussion

The law of iterated logarithms operates “in between” the law of large numbers and the central limit theorem. There are two versions of the law of large numbers — the weak and the strong — and they both claim that the sums Sn, scaled by n−1, converge to zero, respectively in probability and almost surely:

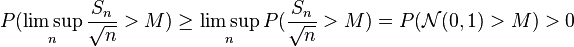

On the other hand, the central limit theorem states that the sums Sn scaled by the factor n−½ converge in distribution to a standard normal distribution. By Kolmogorov's zero-one law, for any fixed M, the probability that the event

occurs is 0 or 1.

Then

occurs is 0 or 1.

Then

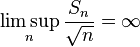

so  with probability 1. An identical argument shows that

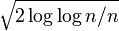

with probability 1. An identical argument shows that  with probability 1 as well. This implies that these quantities cannot converge almost surely. In fact, they cannot even converge in probability, which follows from the equality

with probability 1 as well. This implies that these quantities cannot converge almost surely. In fact, they cannot even converge in probability, which follows from the equality  and the fact that the random variables

and the fact that the random variables  and

and  are independent and both converge in distribution to

are independent and both converge in distribution to  The law of the iterated logarithm provides the scaling factor where the two limits become different:

The law of the iterated logarithm provides the scaling factor where the two limits become different:

Thus, although the quantity  is less than any predefined ε > 0 with probability approaching one, that quantity will nevertheless be dropping out of that interval infinitely often, and in fact will be visiting the neighborhoods of any point in the interval (0,√2) almost surely.

is less than any predefined ε > 0 with probability approaching one, that quantity will nevertheless be dropping out of that interval infinitely often, and in fact will be visiting the neighborhoods of any point in the interval (0,√2) almost surely.

Generalizations and variants

The law of the iterated logarithm (LIL) for a sum of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables with zero mean and bounded increment dates back to Khintchine and Kolmogorov in the 1920s.

Since then, there has been a tremendous amount of work on the LIL for various kinds of dependent structures and for stochastic processes. Following is a small sample of notable developments.

Hartman-Wintner (1940) generalized LIL to random walks with increments with zero mean and finite variance.

Strassen (1964) studied LIL from the point of view of invariance principles.

Stout (1970) generalized the LIL to stationary ergodic martingales.

Acosta (1983) gave a simple proof of Hartman-Wintner version of LIL.

Wittmann (1985) generalized Hartman-Wintner version of LIL to random walks satisfying milder conditions.

Vovk (1987) derived a version of LIL valid for a single chaotic sequence (Kolmogorov random sequence). This is notable as it is outside the realm of classical probability theory.

See also

Notes

- ↑ A. Khinchine. "Über einen Satz der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung", Fundamenta Mathematica, 6:9-20, 1924. (The author's name is shown here in an alternate transliteration.)

- ↑ A. Kolmogoroff. "Über das Gesetz des iterierten Logarithmus". Mathematische Annalen, 101:126-135, 1929. (At the Göttinger DigitalisierungsZentrum web site)

- ↑ Leo Breiman. Probability. Original edition published by Addison-Wesley, 1968; reprinted by Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 1992. (See Sections 3.9, 12.9, and 12.10; Theorem 3.52 specifically.)

- ↑ Varadhan, S. R. S. Stochastic processes. Courant Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 16. Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York; American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 2007.