Language legislation in Belgium

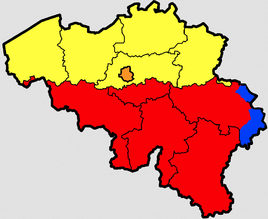

| Dutch-speaking |

French-speaking | ||

| German-speaking |

Bilingual Du./Fr. | ||

| Community: | Region: | ||

| Flemish | Flemish (Flanders) | ||

| Capital (Brussels) | |||

| French | |||

| Walloon | (Wallonia) | ||

| German-speaking | |||

This article outlines the legislative chronology concerning the use of official languages in Belgium.

1830: freedom of languages and linguistic coercion

One of the causes of the Belgian Revolution of the 1830s was the rising dominance of the Dutch language in the administration of the Southern provinces of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.[1] This led to friction with the aristocracy of the southern provinces (modern-day Belgium), whose main language was French.

The citizens in the Flemish provinces wished to engage with the authorities in Dutch. After the Belgian Revolution, the Belgian Constitution guaranteed freedom of languages. In practice, however, the authorities could address themselves to the citizens in the language the authorities wished to use. Government institutions, such as the courts, were dominated by the French-speaking upper classes, and operated in French.[2] French became the lingua franca, despite neither being the everyday language of the Flemish speaking North, nor of the South, where Walloon dialects were in the majority (the exception being the mainly German- or Luxemburgish-speaking environs of Arlon). As universal education developed in Belgium, French was initially the sole language of instruction, causing increasing resentment in the northern half of the country.[3]

In 1860, two Flemish labourers, Jan Coucke and Pieter Goethals, were sentenced to death for the murder of a widow without having understood one single word of their trial.[4] They were found to be innocent only after their execution. The Flemish movement started to advocate for language legislation that would recognise Dutch as an official language.

1873: the first laws on the use of languages

The first law on the use of languages was voted on in 1873. It had perhaps been influence by growing public dissent. In 1872, for example, Jozef Schoep refused to pay a fine of 50 francs for not wanting to declare the birth of his son in French to the municipal administration of Molenbeek. Civil cases on appeal had always led to discussions about the use of languages and Schoep was convicted after an appeal in Cassation.[4]

The first law on the use of languages, supported by Edward Coremans, regulated the use of languages in the Courts in Flanders. Dutch became the major language in Flanders, but oral testimony and penal action were still permitted in French.[5]

1878: the second law on the use of languages

The second law on the use of languages (1878) regulated the use of language in the administrations of Flanders and Brussels. Announcements to the public by government officials had to be in Dutch or in both languages. The correspondence with municipalities or persons would be in Dutch, except if a person wished to be engaged in French.[6] In reality, the law in daily life was hardly applied: Flemish citizens were still being forced to speak French in their communications with the administration, as most civil servants only spoke French.[7]

1883: the third law on the use of languages

Until 1883, education in secondary schools had been entirely in French. The third law on the use of languages was voted on in order to bring change to this situation.[3]

1898: the Law on Equality

In 1898, the Law on Equality was voted. Dutch and French were now to be regarded as equal official languages. Native French speakers in parliament were not willing to learn any Dutch and were therefore not able to read the Dutch texts they were supposed to vote on. This problem did not exist the other way - Dutch speakers would learn French.[8] The law nevertheless was voted on under pressure from the population and thanks to the extension of the suffrage to every male citizen aged 25

1921: a bilingual nation or languages linked to a region

Disagreement about the country's language policy continued. Some segments of French-speaking Wallonia were concerned that current practices could result in Belgium becoming a bilingual country, with French and Dutch being recognised as official languages everywhere. [9] This led to a proposal to split the administration in Belgium to preserve the French-speaking nature of Wallonia and to avoid the possibility that French-speaking civil servants in Wallonia might have to pass a Dutch language examination.

The question was: would Belgium become a bilingual country or a country with two language regions. This implied the choice between:

- Personality principle: Every citizen has the freedom to address the authorities in any of the Belgian languages they so choose, regardless of their region of residence.

- Territoriality principle: The working language in a particular region follows restricted language boundaries, with Belgians from another linguistic community losing all rights to communicate with government authorities.

In 1921, the principle of territoriality was chosen. The principle was confirmed by further legislation, with landmark laws passed in 1932 and 1962. The language areas were outlined according to the principle of the language of the majority of the population.

A provision to the 1932 law determined that a language census should be conducted every ten years. A municipality could only change its linguistic status according to the findings of the census. This resulted in a more flexible principle of territoriality with the possibility for minorities representing at least 30% of the local population to obtain services in their language of origin.

1962: establishment of the language areas and facilities

A 1962 law determined which municipality belonged to what language area. Each Belgian municipality is restricted to only one language area, of which there are four: the Dutch, the French, the German, and the bilingual area Brussels-Capital that includes the Belgian capital city and eighteen surrounding municipalities. From then on, modifications of the linguistic regime would only be possible after changing the law, which requires a majority of each language community. In that same year, the municipality of Voeren (Fourons) went to the Dutch-speaking province of Limburg, and Comines (Komen) and Mouscron (Moeskroen) to the French-speaking province of Hainaut. Those and several other municipalities obtained facilities for the minority language group.

In a municipality with a minority speaking another official language, facilities were provided for the registered residents speaking the latter language, such as for instance education in their language when sixteen parents ask for it. A resident of a municipality has no such rights in a neighbouring municipality. To benefit from these facilities, the facilities have to be asked for by the person concerned. The question was put whether the facilities had to be asked each time or if it was sufficient to ask them once. The 1997 Peeters directive requires that inhabitants of those municipalities ask for facilities each time they want to enjoy them.

Moreover, the facilities are not meant for the authorities, which led in Voeren to a crisis around mayor José Happart, and they are applied only for those residents who ask for them.[10]

Protest raised by French-speakers before ECtHR were mostly unsuccessful (Belgian Linguistics Case).

A number of institutions obtained the authorisation to become bilingual, such as the Catholic University of Leuven.

1970: insertion of the language areas into the Constitution

In 1970, on the completion of the first state reform, four language areas were established by Article 4 of the Constitution. Since then language affiliation of municipalities can only be changed by special law. At the same time language communities were established, with the Flemish and French Community made competent for the regulation of the use of languages in their language area in the areas of administration, education and interaction between employer and employee.

At present

Although the use of languages by the authorities is determined, as well as the use of languages by the administration and the army, the courts, and in the field of education and businesses, the constitutional freedom of language remains absolutely intact in the only thing that remains, the private domain.

In this field, at present, there are still tensions concerning Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde.

Railways

The National Railway Company of Belgium gives its information in the train in the language of the region. This means for instance that in a train driving from Antwerp to Charleroi, announcements are made – during a single train ride – firstly (in the Flemish Region) in Dutch, then (in the Brussels-Capital Region) in both languages (in the language native to the announcing railway employee immediately followed by the other), then (again in the Flemish Region) once more only in Dutch and thereafter (in Wallonia) only in French. This implies that travellers often need to learn the name of their destination in both languages. The ticket inspector however is bound to respond in either language.

Near international places (such as Brussels Airport), German and English translations are also added to the announcements.

Road signs

Similar to the railways, road signs only mention destinations in the local language. So travellers need to learn the destination name in multiple languages. Moreover, when driving in a region, the traveller is expected to understand the language of the region in order to understand some of the road signs.

See also

- Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium

- State reform in Belgium

- Frenchification of Brussels

References

- This article originated as a translation of the article on the Dutch-language Wikipedia.

- "Vlaanderen – Is er nog een toekomst voor België?" (pdf). Les Cahiers du Centre Jean GOL (in Dutch description about scientific committee and publishing centre at the end in French). Centre Jean Gol (Think tank of MR party), Belgium. April 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

- ↑ "The Dutch period (1815 - 1830)". Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ↑ Vande Lanotte, Johan & Goedertier, Geert (2007). Overzicht publiekrecht [Outline public law] (in Dutch). Brugge: die Keure. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-90-8661-397-7.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Vande Lanotte, Johan & Goedertier, Geert (2007). Overzicht publiekrecht [Outline public law] (in Dutch). Brugge: die Keure. pp. 22–24. ISBN 978-90-8661-397-7.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Vande Lanotte, Johan & Goedertier, Geert (2007). Overzicht publiekrecht [Outline public law] (in Dutch). Brugge: die Keure. p. 23. ISBN 978-90-8661-397-7.

- ↑ Vande Lanotte, Johan & Goedertier, Geert (2007). Overzicht publiekrecht [Outline public law] (in Dutch). Brugge: die Keure. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-90-8661-397-7.

- ↑ Vande Lanotte, Johan & Goedertier, Geert (2007). Overzicht publiekrecht [Outline public law] (in Dutch). Brugge: die Keure. p. 24. ISBN 978-90-8661-397-7.

- ↑ Vande Lanotte, Johan & Goedertier, Geert (2007). Overzicht publiekrecht [Outline public law] (in Dutch). Brugge: die Keure. p. 25. ISBN 978-90-8661-397-7.

- ↑ "Séance du 26 janvier 1897" [Session of 26 January 1897] (PDF) (in French). pp. 213–214. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ↑ Alen, André (1994). Le fédéralisme. Approches politique, économique et juridique [Federalism. Political, economic and legal perspective] (in French). Brussels: De Boeck Université. p. 140. ISBN 2-8041-1921-1.

- ↑ Martens, Wilfried (2006). De Memoires: luctor et emergo [Memoires: luctor et emergo] (in Dutch). Tielt: Lannoo. pp. 402–404. ISBN 978-90-209-6520-9.