Language-based security

In computer science, language-based security (LBS) is a set of techniques that may be used to strengthen the security of applications on a high level by using the properties of programming languages. LBS is considered to enforce computer security on an application-level, making it possible to prevent vulnerabilities which traditional operating system security is unable to handle.

Software applications are typically specified and implemented in certain programming languages, and in order to protect against attacks, flaws and bugs an application’s source code might be vulnerable to, there is a need for application-level security; security evaluating the applications behavior with respect to the programming language. This area is generally known as language-based security.

Motivation

The use of large software systems, such as SCADA, is taking place all around the world[1] and computer systems constitute the core of many infrastructures. The society relies greatly on infrastructure such as water, energy, communication and transportation, which again all rely on fully functionally working computer systems. There are several well known examples of when critical systems fail due to bugs or errors in software, such as when shortage of computer memory caused LAX computers to crash and hundreds of flights to be delayed (April 30, 2014).[2][3]

Traditionally, the mechanisms used to control the correct behavior of software are implemented at the operating system level. The operating system handles several possible security violations such as memory access violations, stack overflow violations, access control violations, and many others. This is a crucial part of security in computer systems, however by securing the behavior of software on a more specific level, even stronger security can be achieved. Since a lot of properties and behavior of the software is lost in compilation, it is significantly more difficult to detect vulnerabilities in machine code. By evaluating the source code, before the compilation, the theory and implementation of the programming language can also be considered, and more vulnerabilities can be uncovered.

"So why do developers keep making the same mistakes? Instead of relying on programmers' memories, we should strive to produce tools that codify what is known about common security vulnerabilities and integrate it directly into the development process."

— D. Evans and D. Larochelle, 2002

Objective of Language-based security

By using LBS, the security of software can be increased in several areas, depending on the techniques used. Common programming errors such as allowing buffer overflows and illegal information flows to occur, can be detected and disallowed in the software used by the consumer. It is also desirable to provide some proof to the consumer about the security properties of the software, making the consumer able to trust the software without having to receive the source code and self checking it for errors.

A compiler, taking source code as input, performs several language specific operations on the code in order to translate it into machine readable code. Lexical analysis, preprocessing, parsing, semantic analysis, code generation, and code optimization are all commonly used operations in compilers. By analyzing the source code and using the theory and implementation of the language, the compiler will attempt to correctly translate the high-level code into low-level code, preserving the behavior of the program.

During compilation of programs written in a type-safe language, such as Java, the source code must type-check successfully before compilation. If the type-check fails, the compilation will not be performed, and the source code needs to be modified. This means that, given a correct compiler, any code compiled from a successfully type-checked source program should be clear of invalid assignment errors. This is information which can be of value to the code consumer, as it provides some degree of guarantee that the program will not crash due to some specific error.

A goal of LBS is to ensure the presence of certain properties in the source code corresponding to the safety policy of the software. Information gathered during the compilation can be used to create a certificate that can be provided to the consumer as a proof of safety in the given program. Such a proof must imply that the consumer can trust the compiler used by the supplier and that the certificate, the information about the source code, can be verified.

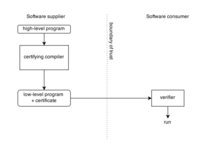

The figure illustrates how certification and verification of low-level code could be established by the use of a certifying compile. The software supplier gains the advantage of not having to reveal the source code, and the consumer is left with the task of verifying the certificate, which is an easy task compared to evaluation and compilation of the source code itself. Verifying the certificate only requires a limited trusted code base containing the compiler and the verifier.

Techniques

Program analysis

The main applications of program analysis are program optimization (running time, space requirements, power consumption etc.) and program correctness (bugs, security vulnerabilities etc.). Program analysis can be applied to compilation (static analysis), run-time (dynamic analysis), or both. In language-based security, program analysis can provide several useful features, such as: type checking (static and dynamic), monitoring, taint checking and control-flow analysis.

Information flow analysis

Information flow analysis can be described as a set of tools used to analyze the information flow control in a program, in order to preserve confidentiality and integrity where regular access control mechanisms come short.

"By decoupling the right to access information from the right to disseminate it, the flow model goes beyond the access matrix model in its ability to specify secure information flow. A practical system needs both access and flow control to satisfy all security requirements."

— D. Denning, 1976

Access control enforces checks on access to information, but is not concerned about what happens after that. An example: A system has two users, Alice and Bob. Alice has a file secret.txt, which is only allowed to be read and edited by her, and she prefers to keep this information to herself. In the system, there also exists a file public.txt, which is free to read and edit for all users in the system. Now suppose that Alice has accidentally downloaded a malicious program. This program can access the system as Alice, bypassing the access control check on secret.txt. The malicious program then copies the content of secret.txt and places it in public.txt, allowing Bob and all other users to read it. This constitutes a violation of the intended confidentiality policy of the system.

Noninterference

Noninterference is a property of programs that does not leak or reveal information of variables with a higher security classification, depending on the input of variables with a lower security classification. A program which satisfies noninterference should produce the same output whenever the corresponding same input on the lower variables are used. This must hold for every possible value on the input. This implies that even if higher variables in the program has different values from one execution to another, this should not be visible on the lower variables.

An attacker could try to execute a program which does not satisfy noninterference repeatedly and systematically to try to map its behavior. Several iterations could lead to the disclosure of higher variables, and let the attacker learn sensitive information about for example the systems state.

Whether a program satisfies noninterference or not can be evaluated during compilation assuming the presence of security type systems.

Security type system

A security type system is a kind of type system that can be used by software developers in order to control the information flow in their code. A security type system consists of several rules that will be used to verify a given information flow policy in a computer program, usually at compile-time. This can reveal if there is any violation of confidentiality or integrity in the program.

Securing low-level code

Vulnerabilities in low-level code are bugs or flaws that will lead the program into a state where further behavior of the program is undefined by the source programming language. The behavior of the low-level program will depend on compiler, runtime system or operating system details. This allows for an attacker to drive the program towards an undefined state, and exploit the behavior of the system.

Common exploits of insecure low-level code lets an attacker perform unauthorized reads or writes to memory addresses. The memory addresses can be either random or chosen by the attacker.

Using safe languages

An approach to achieve secure low-level code is to use safe high-level languages. A safe language is considered to be completely defined by its programmers' manual.[4] Any bug that could lead to implementation-dependent behavior in a safe language will either be detected at compile time or lead to a well-defined error behavior at run-runtime. In Java, if accessing an array out of bounds, an exception will be thrown. Examples of other safe languages are C#, Haskell and Scala.

Defensive execution of unsafe languages

During compilation of an unsafe language run-time checks is added to the low-level code to detect source-level undefined behavior. An example is the use of canaries, which can terminate a program when discovering bounds violations. A downside of using run-time checks such as in bounds-checking is that they impose considerable performance overhead.

Memory protection, such as using non-executable stack and/or heap, can also be seen as additional run-time checks. This is used by many modern operating systems.

Isolated execution of modules

The general idea is to identify sensitive code from application data by analyzing the source code. Once this is done the different data is separated and placed in different modules. When assuming that each module has total control over the sensitive information it contains, it is possible to specify when and how should leave the module. An example is a cryptographic module that can prevent keys from ever leaving the module unencrypted.

Certifying compilation

Certifying compilation is the idea of producing a certificate during compilation of source code, using the information from the high-level programming language semantics. This certificate should be enclosed with the compiled code in order to provide a form of proof to the consumer that the source code was compiled according to a certain set of rules. The certificate can be produced in different ways, e.g. through Proof-carrying code (PCC) or Typed assembly language (TAL).

Proof-carrying code

The main aspects of PCC can be summarized in the following steps:[5]

- The supplier provides an executable program with various annotations produced by a certifying compiler.

- The consumer provides a verification condition, based on a security policy. This is sent to the supplier.

- The supplier runs the verification condition in a theorem prover to produce a proof to the consumer that the program in fact satisfies the security policy.

- The consumer then runs the proof in a proof checker to verify the proof validity.

An example of a certifying compiler is the Touchstone compiler, that provides a PCC formal proof of type- and memory safety for programs implemented in Java.

Typed assembly language

TAL is applicable to programming languages that make use of a type system. After compilation, the object code will carry a type annotation that can be checked by an ordinary type checker. The annotation produced here is in many ways similar to the annotations provided by PCC, with some limitations. However, TAL can handle any security policy that may be expressed by the restrictions of the type system, which can include memory safety and control flow, among others.

Seminars

- Dagstuhl Seminar 03411, Language-Based Security, October 5 – 10 , 2003.

Further reading

- Dexter Kozen, Language Based Security, Cornell University, 1999

- Pieter Agten et al, Recent Developments in Low-Level Software Security, Universiteit Leuven

- Andrei Sabelfeld and Andrew C. Myers, Language-Based Information-Flow Security

- Fred B. Schneider et al, A Language-Based Approach to Security, Carnegie Mellon University, 2000

Books

- G. Barthe, B. Grégoire, T. Rezk, Compilation of Certificates, 2008

- Brian Chess and Gary McGraw, Static Analysis for Security, 2004.

References

- ↑ "Can we learn from SCADA security incidents?". www.oas.org. enisa.

- ↑ "Air Traffic Control System Failed". www.computerworld.com. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "Software Bug Contributed to Blackout". www.securityfocus.com. Retrieved 11 February 2004.

- ↑ Pierce, Benjamin C. (2002). Types and Programming Languages. The MIT Press.

- ↑ Kozen, Dexter (1999). "Language Based Security". Cornell University.