Lagos Colony

| Lagos Colony | |||||

| |||||

|

| |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Lagos | ||||

| Government | British Colony | ||||

| History | |||||

| - | Established | 5 March 1862 | |||

| - | Disestablished | February 1906 | |||

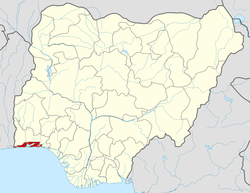

Lagos Colony was a British colonial possession centred on the port of Lagos in what is now southern Nigeria. Lagos was annexed on 6 August 1861 under the threat of force by Commander Beddingfield of HMS Prometheus who was accompanied by the Acting British Consul, William McCoskry. Oba Dosunmu of Lagos (spelled "Docemo" in British documents) resisted the cession for 11 days while facing the threat of violence on Lagos and its people, but capitulated and signed the Lagos Treaty of Cession.[1] Lagos was declared a colony on 5 March 1862.[2] By 1872 Lagos was a cosmopolitan trading center with a population over 60,000.[3] In the aftermath of prolonged wars between the mainland Yoruba states, the colony established a protectorate over most of Yorubaland between 1890 and 1897.[4] The colony and protectorate was incorporated into Southern Nigeria in February 1906, and Lagos became the capital of the protectorate of Nigeria in January 1914.[2] Since then, Lagos has grown to become the largest city in West Africa, with an estimated metropolitan population of over 9,000,000 as of 2011.[5]

Location

Lagos was originally a fishing community on the north of Lagos Island, which lies in Lagos Lagoon, a large protected harbour on the Atlantic coast of Africa in the Gulf of Guinea west of the Niger River delta. The Lagoon is protected from the ocean by long sand spits that run east and west for up to 100 kilometres (62 mi) in both directions.[6] Lagos has a tropical savanna climate with two rainy seasons. The heaviest rains fall from April to July and there is a weaker rainy season in October and November. Total annual rainfall is 1,900 millimetres (75 in). Average temperatures range from 25 °C (77 °F) in July to 29 °C (84 °F) in March.[7]

For many years the staple products of the region were palm oil and palm kernels. Later exports included copra made from the coconut palm, guinea grains, gum copal, camwood and beniseed.[8] Manufacture of palm oil was mainly considered a job for women.[9]

Origins

The earliest incarnation of Lagos was an Awori Yoruba fishing community located on the series of islands and peninsula that form the modern state. The area was inhabited by families that claimed a semi-mythical ancestry from a figure called Olofin.[10] The modern descendants of this figure are the contemporary nobility known as the Idejo or "white cap chiefs" of Lagos. In the 16th century, Lagos island was reputedly sacked by troops of the Oba of Benin during that kingdom's expansionary phase and became known as Eko. The monarchs of Lagos since then have claimed descent from the warrior Ashipa (who is alternately claimed to be a prince of Benin or an Awori freebooter loyal to the Benin throne), although the aristocracy or the Idejo remained Yoruba. Ashipa's son built his palace on Lagos Island, and his grandson moved the seat of government to the palace from the Iddo peninsula. In 1730 the Oba of Lagos invited Portuguese slave traders to the island, and soon a flourishing trade developed.[11]

In the first half of the 19th century the Yoruba hinterland was in a state of near-constant warfare due to internal conflicts and incursions from the northern and western neighbouring states. By now the fortified island of Lagos had become a major centre of the slave trade. The United Kingdom had abolished import of slaves to their colonies in 1807, and abolished slavery in all British territories in 1833. The British became increasingly active in suppressing the slave trade.[12] At the end of 1851 a naval expedition bombarded Lagos into submission,[13] deposed Oba Kosoko, installed Oba Akitoye (who was more amenable), and signed the Great Britain-Lagos treaty that made slavery illegal in Lagos on January 1, 1852. A few months later a vice-consul from the Bight of Benin consulate was posted to the island, and the next year Lagos was upgraded to a full consulate.[12] A Yoruba emigrant, the catechist James White, wrote in 1853 "By the taking of Lagos, England has performed an act which the grateful children of Africa shall long remember ... One of the principal roots of the slave trade is torn out of the soil".[14]

Tensions between the new ruler, Akitoye, and supporters of the deposed Kosoko led to fighting in August 1853. An attempt by Kosoko himself to take the town was defeated, but Akitoye died suddenly on 2 September 1853, perhaps by poison. After consulting with the local chiefs, the consul declared Dosunmu (Docemo), the eldest son of Akitoye, the new Oba.[15] With successive crises and interventions, the consulate evolved over the following years into a form of protectorate.[12] Lagos became a base from which the British would gradually extend their jurisdiction in the form of a protectorate over the hinterland. The process was driven by demands of trade and security rather than by any deliberate policy of expansion.[16] The CMS Grammar School was founded in Lagos on 6 June 1859 by the Church Missionary Society, modelled on the CMS Grammar School in Freetown, Sierra Leone.[17]

Early years

In August 1861 a British naval force entered Lagos and annexed Lagos as a British colony via the Lagos Treaty of Cession. King Dosumu was exiled and the consul William McCoskry became acting governor.[18][fn 1] As a colony, Lagos was now protected and governed directly from Britain.[20] Africans born in the colony were British subjects, with full rights including access to the courts. By contrast, Africans in the later protectorates of southern and northern Nigeria were protected people but remained under the jurisdiction of their traditional rulers.[21]

In the early years, trade with the interior was severely restricted due to a war between Ibadan and Abeokuta. The Ogun River leading to Abeokuta was not safe for canoe traffic, with travellers at risk from Egba robbers. On 14 November 1862 Governor Henry Stanhope Freeman called on all British subjects to return from Abeokuta to Lagos, leaving their property, for which the chiefs of Abeokuta would be answerable to the British government.[22] The acting Governor William Rice Mulliner met the Bashorun of Abeokuta in May 1863, who told him that the recent robberies of traders' property were due to the custom of suppressing trading so as to force the men to war. The plunder would cease when the war was over. In the meantime, traders should not travel to Abeokuta since their safety could not be guaranteed.[23] Despite the dangers of travel in the interior, an 1865 parliamentary committee on the west coast of Africa was informed that Lagos was at no risk from Abeokuta for two reasons. First, the people of Abeokuta were too intelligent to make such an attack. Second, although Abeokuta had 1,000 canoes used for trading with Lagos, they had no war canoes, and even if they did they could never storm the well-defended island from across the lagoon.[24]

Although the slave trade had been suppressed, and slavery was illegal in British territory, slavery still continued in the region. Lagos was seen as a haven by runaway slaves, who were something of a problem for the administration. McCoskry set up a court to hear cases of abuse against slaves and of runaway slaves from the interior, and established a "Liberated African Yard" to give employment to freed runaways until they were able to look after themselves. He did not consider that abolition of slavery in the colony would be practical.[25]

McCloskry, and other merchants in the colony, were opposed to the activities of missionaries which they felt interfered with trade. In 1855 he had been among signatories of a petition to prevent two missionaries who had gone on leave from returning to Lagos. McCloskry communicated his view to the former explorer Richard Francis Burton, who visited Lagos and Abeokuta in 1861 while acting as consul at Fernando Po, and who was also opposed to missionary work.[26] His successor, Freeman, agreed with Burton that the blacks were more likely to be converted by Islam than by Christianity.[27] Freeman attempted to suppress an attempt by Robert Campbell, a Jamaican of part-Scottish, part-African descent, to establish a newspaper in the colony. He consider it would be "a dangerous instrument in the hands of semi-civilized Negroes". The British government did not agree, and the first issue of the Anglo-African, appeared on 6 June 1863.[28]Earlier there had been a newspaper that can truly be described as the first Nigerian newspaper called 'Iwe Iroyin Yoruba fun awon Egba ati Yoruba' in1854.

Growth of the town

A small legislative council was established when the colony was founded in 1861, with the mandate of assisting and advising the Governor but without formal authority, and was maintained until 1922. The majority of members were colonial officials.[29] In 1863 the British established the Lagos Town Improvement Ordinance, aiming to control physical development of the town and surrounding territory.[20] The administration was merged with that of Sierra Leone in 1866, and was transferred to the Gold Coast in 1874. The Lagos elites lobbied intensively to have autonomy restored, which did not happen until 1886.[30]

Colonial Lagos developed into a busy, cosmopolitan port, with an architecture that blended Victorian and Brazilian styles.[7] The Brazilian element was imparted by skilled builders and masons who had returned from Brazil.[31] The black elite was composed of English-speaking "Saros" from Sierra Leone and other emancipated slaves who had been repatriated from Brazil and Cuba.[7] By 1872 the population of the colony was over 60,000, of whom less than 100 were of European origin. In 1876 imports were valued at £476,813 and exports at £619,260.[3]

On 13 January 1874, leaders of the Methodist community, including Charles Joseph George, met to discuss founding a secondary school for members of their communion as an alternative to the CMS Grammar School. After a fund-raising drive, the Methodist Boys School building was opened in June 1877.[32] On 17 February 1881, George was one of the community leaders who laid the foundation stone for the Wesley Church at Olowogbowo, in the west of Lagos Island.[33]

The colony had largely succeeded in eliminating slavery and had become a prosperous trading community, but until the start of the European scramble for Africa the British Imperial government considered that the Lagos colony in some respects a failure. The British had refused to intervene in the politics of the hinterland and cut-throat competition among British and French firms along the Niger had kept it from returning any significant profit.[14]

Yoruba wars

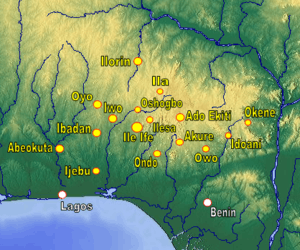

In 1877 a trade war broke out between Ibadan and both Egba Alake (Abeokuta) and Ijebu. Further to the east, the Ekiti and Ijesa revolted against Ibadan rule in 1878, and sporadic fighting continued for the next sixteen years. Assistance from Saro merchants in Lagos in the form of breech-loading rifles gave the Ekiti the advantage. The Lagos government, at that time subordinate to Accra in the Gold Coast, was instructed to stay out of the conflict, despite the damage it was doing to trade, and attempts to mediate by the Saro merchants and by the Fulani emirs were rejected.[4]

By 1884, George Goldie's United African Company had succeeded in absorbing all of his competition and eliminated the French posts from the lower Niger; the situation permitted Britain to claim the entire region at the Berlin Conference the next year. In 1886 Lagos became a separate colony from the Gold Coast under Governor Cornelius Alfred Moloney. The legislative council of the new colony was composed of four official and three unofficial members. Governor Moloney nominated two Africans as unofficial representatives: the clergyman, later bishop James Johnson and the trader Charles Joseph George.[34] At this time the European powers were in intense competition for African colonies while the protagonists in the Yoruba wars were wearying. The Lagos administration, acting through Samuel Johnson and Charles Phillips of the Church Mission Society, arranged a ceasefire and then a treaty that guaranteed the independence of the Ekiti towns. Ilorin refused to cease fighting however, and the war dragged on.[4]

Concerned about the growing influence of the French in nearby Dahomey, the British established a post at Ilaro in 1890.[4] On 13 August 1891 a treaty was signed placing the kingdom of Ilaro under the protection of the British queen.[35] When Governor Gilbert Thomas Carter arrived in 1891, he followed an aggressive policy. In 1892 he attacked Ijebu, and in 1893 made a tour of Yorubaland signing treaties, forcing the armies to disperse, and opening the way for construction of a railway from Lagos to Ibadan.[4] Thus on 3 February 1893, Carter signed a treaty of protection with the Alafin of Oyo and on 15 August 1893, acting Governor George Chardin Denton signed a protectorate agreement with Ibadan.[36] Colonial control was firmly established throughout the region after the bombardment of Oyo in 1895 and the capture of Ilorin by the Royal Niger Company in 1897.[4]

Later years

In 1887 Captain Maloney, the Governor, gave a report to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in which he outlined plans for a Botanic Station at Lagos with the purpose of developing indigenous trees and plants that had commercial value.[8] By 1889 rubber had been introduced to the colony, and was promising excellent yields and quality. A report that year described other products including gum and coconut oil, for which a small-scale crushing business had promise, various fibres, camwood, borwood and Indigo, also seen as having large potential.[37]

The growth of the city of Lagos was largely unplanned, impeded by the complex of swamps, canals and sand spits.[38] William MacGregor, governor from 1898 to 1903, instituted a campaign against the prevalent malaria, draining the swamps and destroying as far as possible the mosquitoes that were responsible for the spread of the disease.[39]

Telephone links with Britain were established by 1886, and electric street lighting in 1898.[31] In August 1896, Charles Joseph George and G.W. Neville, both merchants and both unofficial members of the Legislative Council, presented a petition urging construction of the railway terminus on Lagos Island rather than at Iddo, and also asking for the railway to be extended to Abeokuta. George was the leader of the delegation making this request, and described its many commercial advantages.[40] A major strike broke out in the colony in 1897, which has been described as the "first major labour protest" in African history.[41]

On 21 February 1899 the Alake of the Egba signed an agreement opening the way for construction of a railway through their territory, [42] and the new railway from Aro to Abeokuta was opened by the Governor in December 1901, in the presence of the Alake.[43]

In 1901 the first qualified African lawyer in the colony, Christopher Sapara Williams, was nominated to the Legislative Council, serving as a member until his death in 1915.[44] In 1903 there was a crisis over the payment of the tolls that were collected from traders by native rulers, although Europeans were exempted. The alternative was to replace the tolls by a subsidy. MacGregor requested views from Williams, Charles Joseph George and Obadiah Johnson as indigenous opinion leaders. All were in favour of retaining the tolls to avoid upsetting the rulers.[45] In 1903 Governor MacGregor's administration prepared a Newspaper Ordinance ostensibly designed to prevent libels being published. George, Williams and Johnson, the three Nigerian council members, all objected on the grounds that the ordinance would inhibit freedom of the press. George said "any obstacle in the way of publication of newspapers in this colony means throwing Lagos back to its position forty or fifty years ago". Despite these objections, the ordinance was passed into law.[46]

Walter Egerton was the last Governor of Lagos Colony, appointed in 1903. Egerton enthusiastically endorsed the extension of the Lagos – Ibadan railway onward to Oshogbo, and the project was approved in November 1904. Construction began in January 1905 and the line reached Oshogbo in April 1907.[47] The colonial office wanted to amalgamate the Lagos Colony with the protectorate of Southern Nigeria, and in August 1904 also appointed Egerton as High Commissioner for the Southern Nigeria Protectorate. He held both offices until 28 February 1906.[48] On that date the two territories were amalgamated, with the combined territory called the Colony and Protectorate of Southern Nigeria. In 1914, the Governor-General Sir Frederick Lugard amalgamated this territory with the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria to form the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria.[49]

Lagos was the capital of Nigeria until 1991, when that role was ceded to the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, and remains the commercial capital.[31] The estimated population in 2011 was over 9 million.[5]

Governors

Governors of the Lagos Colony were as follows:[2]

| Took office | Left Office | Governor | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 August 1861 | 22 January 1862 | William McCoskry | Acting |

| 22 January 1862 | April 1865 | Henry Stanhope Freeman | |

| 1863 | 25 July 1863 | William Rice Mulliner | Acting. d. 25 July 1863 aged 29. |

| August 1863 | 19 February 1866 | John Hawley Glover | Acting to April 1865. Administrator or colonial secretary until 1872. |

From 1866 to 1886 Lagos was subordinate first to Sierra Leone, then to Gold Coast.

| Took office | Left Office | Governor | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 January 1886 | 1891 | Cornelius Alfred Moloney | |

| 1889 | 1890 | George Denton | Acting for Moloney |

| 1891 | 1897 | Sir Gilbert Thomas Carter | |

| 1897 | 1899 | Henry Edward McCallum | |

| 1899 | 1903 | Sir William MacGregor | |

| 1903 | 16 February 1906 | Walter Egerton |

See also

Notes

- ↑ The British had arranged to pay Dosunmu, the Oba of Lagos an annual grant of £1,000 for his lifetime, after which they would assume full sovereignty of the colony. When Dosunmu died in 1884, Africans led by James Johnson and supported by George demanded a reasonable payment for his son, Oyekan. This was agreed by the administration, but only reluctantly.[19]

References

- ↑ Elebute, Adeyemo. The Life of James Pinson Labulo Davies: A Colossus of Victorian Lagos. Kachifo Limited/Prestige. pp. 143–145. ISBN 9789785205763.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Worldstatesmen.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Higman 1879, pp. 70.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Dupuy.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 City Mayors.

- ↑ Adeaga 2005, pp. 226ff.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Library of Congress.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Royal Botanic Gerdens, pp. 150.

- ↑ Mann 2007, pp. 394.

- ↑ African Cities (African-Europe Group for Interdisciplinary Studies) by Francesca Locatelli and Paul Nugent (30 June 2009)

- ↑ Williams 2008, pp. 110.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Smith 1979, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Onyeozili 2005.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Smith 1979, pp. 132.

- ↑ Smith 1979, pp. 52–55.

- ↑ Ezera 1964, pp. 13.

- ↑ CMS School History.

- ↑ Sterling 1996, pp. 223.

- ↑ Ayandele 1970, pp. 174.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Falola & Salm 2004, pp. 255.

- ↑ Page 2003, pp. 425.

- ↑ Foreign and Commonwealth.

- ↑ Great Britain 1865.

- ↑ Great Britain 1865b.

- ↑ Mann 2007, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Peel 2003, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Lyons & Lyons 2004, pp. 62.

- ↑ Benesch 2004, pp. 141.

- ↑ Ezera 1964, pp. 22.

- ↑ Falola & Salm 2004, pp. 282.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Williams 2008, pp. 111.

- ↑ Methodist Boys School.

- ↑ Wesley Cathedral.

- ↑ Ayandele 1970, pp. 164.

- ↑ Johnson & Johnson 2010, pp. 668.

- ↑ Johnson & Johnson 2010, pp. 654.

- ↑ Society of Chemical Industry.

- ↑ Ross, Morgan & Heelas 2000, pp. 8.72.

- ↑ Joyce 1974, pp. 158–160.

- ↑ Olukoju 2004, pp. 15.

- ↑ Hopkins 1966, p. 133.

- ↑ Johnson & Johnson 2010, pp. 658.

- ↑ "Latest intelligence – Lagos" The Times (London). Tuesday, 17 December 1901. (36640), p. 5.

- ↑ Jimilehin 2010.

- ↑ Falola & Adebayo 2000, pp. 115.

- ↑ Ogbondah 1992, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Carland 1985, pp. 148.

- ↑ Carland 1985, pp. 82.

- ↑ Ezera 1964, pp. 14.

Bibliography

- Adeaga, Olusegun (2005). "A sustainable flood management plan for the Lagos environs". Sustainable water management solutions for large cities: the proceedings of the international symposium on Sustainable Water Management for Large Cities (S2). IAHS. ISBN 1-901502-97-X.

- Ayandele, Emmanuel Ayankanmi (1970). Holy Johnson, pioneer of African nationalism, 1836–1917. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-1743-1.

- Benesch, Klaus (2004). African diasporas in the New and Old Worlds: consciousness and imagination. Rodopi. ISBN 90-420-0880-6.

- Carland, John M. (1985). The Colonial Office and Nigeria, 1898–1914. Hoover Press. ISBN 0-8179-8141-1.

- City Mayors Statistics. "The largest cities in the world and their mayors". Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- "CMS School History". Old Grammarians Society. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- The Dupuy Institute. "The Yoruba War 1877–1893". Armed Conflict Events Database. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- Hopkins, A. G. (1966). "The Lagos Strike of 1897: An Exploration in Nigerian Labour History". Past & Present (35): 133–155. JSTOR 649969.

- Ezera, Kalu (1964). Constitutional developments in Nigeria: an analytical study of Nigeria's constitution-making developments and the historical and political factors that affected constitutional change. Cambridge University Press.

- Falola, Toyin; Adebayo, Akanmu Gafari (2000). Culture, politics & money among the Yoruba. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-418-5.

- Falola, Toyin; Salm, Steven J. (2004). Nigerian cities. Africa World Press. ISBN 1-59221-169-0.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office (1859). British and foreign state papers, Volume 54. H.M.S.O.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1865). Reports from committees. Ordered to be printed. p. 178.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1865). House of Commons papers 5. HMSO.

- Higman, Thomas (1879). "Lagos". John Heywood's atlas and geography of the British Empire. John Heywood.

- Jimilehin, Oladipo (27 April 2010). "The legal profession and role of lawyers in Nigerian politics". Nigerian Tribune. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- Johnson, Samuel; Johnson, Obadiah (2010). The History of the Yorubas: From the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the British Protectorate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1-108-02099-2.

- Joyce, R. B. (1974). "MacGregor, Sir William (1846–1919)". Australian Dictionary of Biography (Melbourne University Press) 5. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- "A Country Study: Nigeria". Library of Congress. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- Lyons, Andrew Paul; Lyons, Harriet (2004). Irregular connections: a history of anthropology and sexuality. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8036-X.

- Mann, Kristin (2007). Slavery and the birth of an African city: Lagos, 1760–1900. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34884-6.

- "Methodist Boys High School Lagos: History". Methodist Boys High School Lagos. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- Ogbondah, Chris W. (1992). "British Colonial Authoritarianism, African Military Dictatorship and the Nigerian Press" (PDF). Africa Media Review (African Council for Communication Education) 6 (3). Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- Olukoju, Ayodeji (2004). The "Liverpool" of West Africa: the dynamics and impact of maritime trade in Lagos, 1900–1950. Africa World Press. ISBN 1-59221-292-1.

- Onyeozili, Emmanuel C. (April 2005). "Obstacles to Effective Policing in Nigeria" (PDF). African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Page, Melvin E. (2003). Colonialism: an international social, cultural, and political encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-335-1.

- Peel, J. D. Y. (2003). Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21588-9.

- Ross, Simon; Morgan, John; Heelas, Richard (2000). Essential AS Geography. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 0-7487-5175-0.

- Royal Botanic Gardens (1887). Kew bulletin 1–2. H.M. Stationery Off.

- Society of Chemical Industry (Great Britain) (1889). "The Produce of Lagos". Journal of the Society of Chemical Industry 8. Society of Chemical Industry.

- Smith, Robert Sydney (1979). The Lagos consulate, 1851–1861. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03746-4.

- Sterling, Dorothy (1996). The making of an Afro-American: Martin Robison Delany, 1812–1885. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80721-1.

- "WESLEY CATHEDRAL CHOIR OLOWOGBOWO: About Us". WESLEY CATHEDRAL CHOIR OLOWOGBOWO. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- Williams, Lizzie (2008). Nigeria. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 1-84162-239-7.

- Worldstatesmen. "Nigeria". Retrieved 24 May 2011.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

.jpg)