Lacunary function

In analysis, a lacunary function, also known as a lacunary series, is an analytic function that cannot be analytically continued anywhere outside the radius of convergence within which it is defined by a power series. The word lacunary is derived from lacuna (pl. lacunae), meaning gap, or vacancy.

The first known examples of lacunary functions involved Taylor series with large gaps, or lacunae, between the non-zero coefficients of their expansions. More recent investigations have also focused attention on Fourier series with similar gaps between non-zero coefficients. There is a slight ambiguity in the modern usage of the term lacunary series, which may be used to refer to either Taylor series or Fourier series.

A simple example

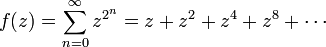

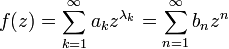

Consider the lacunary function defined by a simple power series:

The power series converges uniformly on any open domain |z| < 1. This can be proved by comparing f with the geometric series, which is absolutely convergent when |z| < 1. So f is analytic on the open unit disk. Nevertheless f has a singularity at every point on the unit circle, and cannot be analytically continued outside of the open unit disk, as the following argument demonstrates.

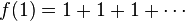

Clearly f has a singularity at z = 1, because

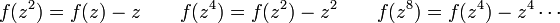

is a divergent series. But since

we can see that f has a singularity at a point z when z2 = 1 (that is, when z = ±1), and also when z4 = 1 (that is, when z = ±1 or when z = ±i). By the induction suggested by the above equations, f must have a singularity at each of the 2nth roots of unity for all natural numbers n. The set of all such points is dense on the unit circle, hence by continuous extension every point on the unit circle must be a singularity of f.[1]

An elementary result

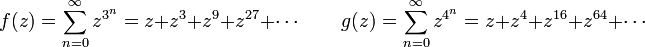

Evidently the argument advanced in the simple example can also be applied to show that series like

also define lacunary functions. What is not so evident is that the gaps between the powers of z can expand much more slowly, and the resulting series will still define a lacunary function. To make this notion more precise some additional notation is needed.

We write

where bn = ak when n = λk, and bn = 0 otherwise. The stretches where the coefficients bn in the second series are all zero are the lacunae in the coefficients. The monotonically increasing sequence of positive natural numbers {λk} specifies the powers of z which are in the power series for f(z).

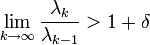

Now a theorem of Hadamard can be stated.[2] If

where δ > 0 is an arbitrary positive constant, then f(z) is a lacunary function that cannot be continued outside its circle of convergence. In other words, the sequence {λk} doesn't have to grow as fast as 2k for f(z) to be a lacunary function – it just has to grow as fast as some geometric progression (1 + δ)k. A series for which λk grows this quickly is said to contain Hadamard gaps. See Ostrowski-Hadamard gap theorem.

Lacunary trigonometric series

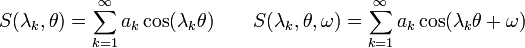

Mathematicians have also investigated the properties of lacunary trigonometric series

for which the λk are far apart. Here the coefficients ak are real numbers. In this context, attention has been focused on criteria sufficient to guarantee convergence of the trigonometric series almost everywhere (that is, for almost every value of the angle θ and of the distortion factor ω).

- Kolmogorov showed that if the sequence {λk} contains Hadamard gaps, then the series S(λk, θ, ω) converges (diverges) almost everywhere when

- converges (diverges).

- Zygmund showed under the same condition that S(λk, θ, ω) is not a Fourier series representing an integrable function when this sum of squares of the ak is a divergent series.[3]

A unified view

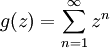

Greater insight into the underlying question that motivates the investigation of lacunary power series and lacunary trigonometric series can be gained by re-examining the simple example above. In that example we used the geometric series

and the Weierstrass M-test to demonstrate that the simple example defines an analytic function on the open unit disk.

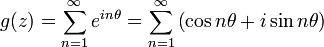

The geometric series itself defines an analytic function that converges everywhere on the closed unit disk except when z = 1, where g(z) has a simple pole.[4] And, since z = eiθ for points on the unit circle, the geometric series becomes

at a particular z, |z| = 1. From this perspective, then, mathematicians who investigate lacunary series are asking the question: How much does the geometric series have to be distorted – by chopping big sections out, and by introducing coefficients ak ≠ 1 – before the resulting mathematical object is transformed from a nice smooth meromorphic function into something that exhibits a primitive form of chaotic behavior?

See also

Notes

- ↑ (Whittaker and Watson, 1927, p. 98) This example apparently originated with Weierstrass.

- ↑ (Mandelbrojt and Miles, 1927)

- ↑ (Fukuyama and Takahashi, 1999)

- ↑ This can be shown by applying Abel's test to the geometric series g(z). It can also be understood directly, by recognizing that the geometric series is the Maclaurin series for g(z) = z/(1−z).

References

- Katusi Fukuyama and Shigeru Takahashi, Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, vol. 127 #2 pp. 599–608 (1999), "The Central Limit Theorem for Lacunary Series".

- Szolem Mandelbrojt and Edward Roy Cecil Miles, The Rice Institute Pamphlet, vol. 14 #4 pp. 261–284 (1927), "Lacunary Functions".

- E. T. Whittaker and G. N. Watson, A Course in Modern Analysis, fourth edition, Cambridge University Press, 1927.

External links

- Fukuyama and Takahashi, 1999 A paper (PDF) entitled The Central Limit Theorem for Lacunary Series, from the AMS.

- Mandelbrojt and Miles, 1927 A paper (PDF) entitled Lacunary Functions, from Rice University.

- MathWorld article on Lacunary Functions