Labour supply

In mainstream economic theories, the supply of labour is the total hours (adjusted for intensity of effort) that workers wish to work at a given real wage rate. It is frequently represented graphically by a labour supply curve, which shows hypothetical wage rates plotted vertically and the amount of labour that an individual or group of individuals is willing to supply at that wage rate plotted horizontally.

Dynamics

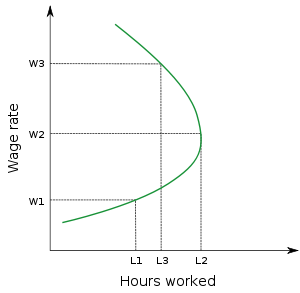

Labour supply curves are derived from the 'labour-leisure' trade-off. More hours worked earn higher incomes but necessitate a cut in the amount of leisure that workers enjoy. Consequently there are two effects on the amount of labour desired to be supplied due to a change in the real wage rate. As, for example, the real wage rate rises the opportunity cost of leisure increases. This tends to cause workers to supply more labour (the "substitution effect"). However, also as the real wage rate rises, workers earn a higher income for a given number of hours. If leisure is a normal good − the demand for it increases as income increases − this increase in income will tend to cause workers to supply less labour in order to "spend" the higher income on leisure (the "income effect"). If the substitution effect is stronger than the income effect then the labour supply curve will be upward sloping;[1] if beyond a certain wage rate the income effect is stronger than the substitution effect, then the labour supply curve is backward bending.

From a Marxist view a labour supply is a core requirement in a capitalist society. In order to avoid labour shortage and ensure a labour supply, a large portion of the population must not possess sources of self-provisioning, which would allow them to be independent, and they must instead be compelled, in order to survive, to sell their labour for a subsistence wage.[2][3] In the pre-industrial economies wage labour was generally undertaken only by those with little or no land of their own.[4]

See also

- Labour economics−Neoclassical microeconomic model of labour supply

- Backward bending supply curve of labour

Marxist theory:

- Reserve army of labour

- Proletarisation

Notes

References

- Maurice Dobb (1947) Studies in the Development of Capitalism New York: International Publishers Co., Inc.

- David Harvey (1989) The Condition of Postmodernity

- Peter J. Bowden (1967) chapter Agricultural prices, farm profits, and rents, section "A. The long-term movement of agricultural prices" - "The long-term trend of prices". Published in The agrarian history of England and Wales, vol 4: 1500-1640, edited by Joan Thirsk. Also published in Chapters from the Agrarian History of England and Wales, 1500-1750 p. 18

Bibliography

- G. Arrighi (1970) Labour supplies in historical perspective: A study of the proletarianization of the African peasantry in Rhodesia Published in: Journal of Development Studies, Volume 6, Issue 3 April 1970, pages 197 - 234 doi:10.1080/00220387008421322

- Peter J. Bakewell (1971) Silver Mining and Society in Colonial Mexico: Zacatecas, 1546-1700 Cambridge University Press pp. 124–5

- Brooke Larson, William Roseberry (1998) Cochabamba, 1550-1900: Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia Published by Duke University Press, 1998 ISBN 0-8223-2088-6, ISBN 978-0-8223-2088-3 p. 55

- Michael Cowen, Robert W. ShentonDoctrines of Development pp. 186, 312-3, 336

--

- Douglass North (1990) Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Robert Brenner (1976) Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe, Past and Present 70: 30-75.

- Brenner, Robert (1985) The Agrarian Roots of European Capitalism, in T. H. Aston and C. H. E. Philpin, eds, The Brenner Debate: Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ellen Meiksins Wood (2002) The Origins of Capitalism: A Longer View London: Verso

- Mushtaq Husain Khan [The Capitalist Transformation] pp. 7–9, 11-12 (published in Jomo, K.S. and Reinert, Eric S. eds. 2005. The Origins of Development Economics: How Schools of Economic Thought Have Addressed Development. New Delhi: Tulika Books and London: Zed Press pp. 69–80)

Journals

- Journal of Labor Economics

- Review of Economics of the Household

- Journal of Human Resources

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||