Labor demand

In economics, labor demand refers to the number of hours of hiring that an employer is willing to do based on the various exogenous (externally determined) variables it is faced with, such as the wage rate, the unit cost of capital, the market-determined selling price of its output, etc. The function specifying the quantity of labor that would be demanded at any of various possible values of these exogenous variables is called the labor demand function.[1]

Perfect competitor

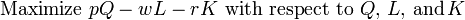

The labor demand function of a competitive firm is determined by the following profit maximization problem:

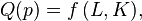

where p is the exogenous selling price of the produced output, Q is the chosen quantity of output to be produced per month, w is the hourly wage rate paid to a worker, L is the number of labor hours hired (the quantity of labor demanded) per month, r is the cost of using a machine (capital) for an hour (the "rental rate"), K is the number of hours of machinery used (the quantity of capital demanded) per month, and f is the production function specifying the amount of output that can be produced using any of various combinations of quantities of labor and capital. This optimization problem involves simultaneously choosing the levels of labor, capital, and output. The resulting labor demand, capital demand, and output supply functions are of the general form

and

Ordinarily labor demand will be an increasing function of the product's selling price p (since a higher p makes it worthwhile to produce more output and to hire additional units of input in order to do so), and a decreasing function of w (since more expensive labor makes it worthwhile to hire less labor and produce less output). The rental rate of capital, r, has two conflicting effects: more expensive capital induces the firm to substitute away from physical capital usage and into more labor usage, contingent on any particular level of output; but the higher capital cost also induces the firm to produce less output, requiring less usage of both inputs. Depending on which effect predominates, labor demand could be either increasing or decreasing in r.

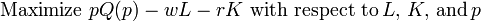

Monopolist

If the firm is a monopolist, its optimization problem is different because it cannot take its selling price as given: the more it produces, the lower will be the price it can obtain for each unit of output, according to the market demand curve for the product. So its profit-maximization problem is

where Q(p) is the market demand function for the product. The constraint equates the amount that can be sold to the amount produced. Here labor demand, capital demand, and the selling price are the choice variables, giving rise to the input demand functions

and the pricing function

There is no output supply function for a monopolist, because a supply function pre-supposes the existence of an exogenous price.

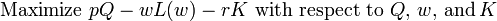

Monopsonist in the labor market

If the firm is a perfect competitor in the goods market but is a monopsonist in the labor market — meaning that it is the only buyer of labor, so the amount it demands influences the wage rate — then its optimization problem is

where L(w) is the market labor supply function of workers which faces the firm. Here the firm cannot choose an amount of labor to demand independently of the wage rate, because the labor supply function links the quantity of labor that can be hired to the wage rate; therefore there is no labor demand function.

See also

References

- ↑ Varian, Hal, 1992, Microeconomic Analysis, 3rd Ed., W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. New York.