LGBT rights in Poland

| LGBT rights in Poland | |

|---|---|

|

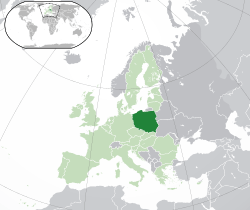

Location of Poland (dark green) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) | |

| Same-sex sexual activity legal? | Legal. Both male and female never criminalised; legality reconfirmed in 1932 |

| Gender identity/expression | Transsexual persons allowed to change legal gender |

| Military service | Gays and lesbians allowed to serve |

| Discrimination protections | Sexual orientation protection in labour code since 2003 (see below) |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | No recognition of same-sex relationships. |

Restrictions: | Same-sex marriage constitutionally banned. |

| Adoption | Single LGBT persons can adopt, but same-sex couples are not allowed to at all |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in Poland may face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are legal in Poland, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples. However, homosexuality was never illegal under Polish law, and Poland was one of the first countries to avoid punishing homosexuality in early modern era. This was formally codified in 1932, and when Poland introduced an equal age of consent for homosexuals and heterosexuals was set at 15.[1][2] Poland is one of few countries where homosexuals are allowed to donate blood. However, there are incidents of discrimination against gay blood donors.[3]

Many left-wing political parties (Alliance of the Democratic Left, Labour Union, Social Democracy, Palikot's Movement and others) support the gay rights movement and are in favour of appropriate changes in legislation. Individual voices of support can also be heard from the liberal right in the Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, currently in power).

History

There was never any anti-homosexual law under a free Polish government (excluding homosexual prostitution 1932–1969).

During the Partitions of Poland (1795–1918) laws prohibiting homosexuality were imposed by the occupying powers. Homosexuality was recognized by law in 1932 with the introduction of a new penal code. The age of consent was set to 15, equal to that of heterosexual partners.[4] Homosexual prostitution was legalized in 1969.

Homosexuality was deleted from the list of diseases in 1991.

Acceptance for LGBT people in Polish society increased in the 1990s and early 2000s, mainly amongst younger people and those living in larger cities. There exists a "gay scene" with clubs all around the country, most of them are located in the large urban areas. There are also a number of gay rights organizations, the two biggest ones being Campaign Against Homophobia and Lambda Warszawa.

In October 2011, Poland elected its first openly gay member of parliament Robert Biedroń, as well as its first transsexual MP, Anna Grodzka.[5]

Public laws

Homosexuality was recognized by law in 1932 with the introduction of a new penal code. The age of consent was set to 15, equal to that of heterosexual partners.[6] Homosexual prostitution was legalized in 1969.

Recognition of same-sex relationships

There is no legal recognition of same-sex couples. Same-sex marriage is constitutionally banned. Article 18 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland defines marriage as a union of a man and a woman and places it under the protection and care of the Republic of Poland.[7]

In late 2003, Polish Senator Maria Szyszkowska proposed civil unions for same-sex couples, calling for "registered partnerships", similar to the French Pacte civil de solidarité (PACS). On 3 December 2004, the Senate (the upper chamber of the Polish Parliament) adopted the Civil Unions project. The bill lapsed in the 2005 general election.

In 2004, Warsaw's Municipal Transport Authority decision to allow cohabiting partners of gay and lesbian employees to travel free on the city's public transport system was the first case of recognition of same-sex couples in Poland. In 2007, a decision of Chorzów’s City Center of Social Assistance recognized homosexual relationships.

On 23 February 2007, the verdict of the Appeal Court in Białystok recognized same-sex cohabitation (File I ACa 590/06).[8] On 6 December 2007, it was confirmed by Judgement of The Supreme Court of Warsaw (IV CSK 301/2007and IV CSK 326/2007).[9][10]

At the end of 2010, the Court in Złotów decided that the same-sex partner of a woman who had died was entitled to continue the lease on their communal apartment. The municipality appealed the verdict, but the District Court in Poznań rejected the appeal. Thus, the decision of the Court in Złotów became final. In support of the judge relied, for the first time, on the European Convention on Human Rights,[11] which had ruled in Kozak v. Poland that gays and lesbians have the right to inherit from their partners.[12] Another similar case about the right to housing of a deceased male partner is pending in the Court in Warsaw.[13] However, in this case the District Court refused to recognise the tenancy law for the partner of the deceased tenant although earlier (2010), the Court in Strasbourg had ruled that this was discrimination.[14]

The major opposition to introducing same-sex marriages or civil unions comes from the Roman Catholic Church, which is influential politically, holding a considerable degree of influence in the state.[5] The Church also enjoys immense social prestige.[15] The Church holds that homosexuality is a deviation.[5] The nation is 95% Roman Catholic, with 54% practicing every week.[16]

Adoption and family planning

Although same-sex couples can't adopt, single LGBT persons can.

Discrimination protections

Anti-discrimination laws were added to the Labour Code in 2003. The Polish Constitution guarantees equality in accordance with law and prohibits discrimination based on "any reason".[7] The proposal to include a prohibition of discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the constitution in 1995 was rejected, after strong Catholic Church objections.[17]

In 2007, an anti-discrimination law was under preparation by the Ministry of Labour that would prohibit discrimination on different grounds, including sexual orientation, not only in work and employment, but also in social security and social protection, health care, and education, although the provision of and access to goods and services would only be subject to a prohibition of discrimination on grounds of race or ethnic origin.[18] On 1 January 2011, a new law on equal treatment has entered into force. It only prohibits sexual orientation discrimination in employment.[19][20]

Military service

Gay people are not banned from military service. There is an unwritten "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy in the Polish Armed Forces.[21]

Social attitudes and public opinion

A survey from 2005 found 89% of the population stating that they considered homosexuality an unnatural activity. Half believed homosexuality should be tolerated.[22]

An opinion poll conducted in late 2006 at the request of the European Commission indicated Polish public opinion was overwhelmingly opposed to same-sex marriage and to adoption by gay couples. The Eurobarometer 66[23] poll found that 74% and 89% of Poles respectively were opposed to same-sex marriage and adoption by gay couples. Of the EU member states surveyed, only Latvia and Greece had higher levels of opposition.[24][25][26] A poll in July 2009 showed that 87% of Poles were against gay adoption.[27] A poll from 23 December 2009 for Newsweek Poland reported another shift towards more positive attitudes. Sixty percent of respondents stated that they would have no objections to having an openly gay minister or a head of the government.[28]

A 2010 study published in the newspaper Rzeczpospolita revealed that Poles overwhelmingly oppose gay marriage and the adoption of children by gay couples. 80% of Poles opposed gay marriage and 93% of Poles opposed the adoption of children by gay couples.[29]

In 2010, an IIBR opinion poll conducted for Newsweek Poland found that 43% of Poles agreed that openly gay people should be banned from military service. 38% thought that such a ban should not exist in the Polish Army.[30]

A majority of Poles also oppose Pride parades – a 2008 study revealed that 66% of Poles believe that gay people should not have the right to organize public demonstrations, 69% of Poles believe that gay people should not have the right to show their way of life. Also, 37% of Poles believe that gay people should have the right to engage in sexual activity, with 37% believing they should not.[31]

In 2011, according to a poll by TNS Polska, 54% of Poles supported same-sex partnerships while 27% supported same-sex marriage.[32]

In a 2013 opinion poll conducted by CBOS, 68% of Poles were against gays and lesbians publicly showing their way of life, 65% of Poles were against same-sex civil unions, 72% were against same-sex marriage and 88% were against adoption by same-sex couples.[33]

Opinion polls

| Poles' support for parenthood: (CBOS poll) | 2014[34] | |

|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | |

| right for a lesbian to parent a child of her female partner | 56% | 35% |

| the situation above is morally acceptable | 41% | 49% |

| right for a gay (couple) to foster the child of a deceased sibling | 52% | 39% |

| the situation above is morally acceptable | 38% | 53% |

| Poles' support for: (CBOS poll) | 2001[35] | 2002[36] | 2003[37] | 2005[38] | 2008[39] | 2010[40] | 2011[41] | 2013[42] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | |

| registered partnerships | - | – | 15% | 76% | 34% | 56% | 46% | 44% | 41% | 48% | 45% | 47% | 25% | 65% | 33% | 60% |

| same-sex marriages | 24% | 69% | - | – | - | – | 22% | 72% | 18% | 76% | 16% | 78% | - | – | 26% | 68% |

| adoption rights | 8% | 84% | - | – | 8% | 84% | 6% | 90% | 6% | 90% | 6% | 89% | - | – | 8% | 87% |

| Support for registered partnerships (CBOS poll)[43] | opposite-sex couples | same-sex couples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | YES | NO | |

| registered partnerships (VI 2011) | 83% | 10% | 25% | 65% |

| registered partnerships (II 2013) | 85% | 11% | 33% | 60% |

| Poles' support for: (PBS poll) | 2013[44] | |

|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | |

| registered partnerships | 40% | 46% |

| same-sex marriages | 30% | 56% |

| adoption rights | 17% | 70% |

| Poles' support for: (TNS OBOP poll) | 2011[45] | |

|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | |

| registered partnerships | 54% | 41% |

| same-sex marriages | 27% | 68% |

| adoption rights | 7% | 90% |

| Support for registered partnerships (OBOP poll)[46] | opposite-sex couples | same-sex couples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | YES | NO | |

| registered partnerships (III 2013) | 67% | 34% | 47% | 53% |

| Poles' support for: (Homo Homini poll) | 2013[47] | |

|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | |

| registered partnerships | 55% | 39% |

| same-sex marriages | 27% | 69% |

| adoption rights | 14% | 84% |

| Support for registered partnerships 2012 (CEAPP poll)[48] | opposite-sex couples | same-sex couples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | YES | NO | |

| registered partnerships | 72% | 17% | 23% | 65% |

| right to obtain medical information | 86% | - | 68% | - |

| right to inherit | 78% | - | 57% | - |

| rights to common tax accounting | 75% | - | 55% | - |

| right to inherit the pension of a deceased partner | 75% | - | 55% | - |

| right to a refund in vitro treatments | 58% | - | 20% | - |

| right to adopt a child | 65% | - | 16% | - |

| Acceptance of a homosexual as a... (CBOS, July 2005[49]) | Gay (Yes) | Gay (No) | Lesbian (Yes) | Lesbian (No) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighbour | 56% | 38% | 54% | 40% |

| Co-worker | 45% | 50% | 42% | 53% |

| Boss | 41% | 53% | 42% | 53% |

| MP | 37% | 57% | 38% | 56% |

| Teacher | 19% | 77% | 21% | 75% |

| Child-minder | 11% | 86% | 14% | 83% |

| Priest | 13% | 82% | - | - |

| Does not tolerate homosexuals at all | - | 40% | - | 43% |

Attitude of politicians

The parties on the left of the political scene generally approve of the postulates of the gay rights movement and would vote in favour of the new LGBT legislation. Palikot's Movement (third largest party in parliament) & Democratic Left Alliance (5th largest party), are strong supporters of gay rights and same-sex marriage. The two major parties (PO & PiS) are generally against any changes in legislation, although of the two, PiS takes a stronger oppositional stance on gay rights issues. Lech Kaczyński, the president to 2010, harboured views and opinions which repeatedly caused tension between Poland and gay rights activists in other parts of Europe.

Giertych's anti-homosexual law

In March 2007 Roman Giertych proposed a bill that would ban homosexual people from the teaching profession and would also allow sacking those teachers who promote "the culture of homosexual lifestyle".[50] At that time Giertych was a deputy prime minister and a minister of education from a small right-wing and ultra-Catholic party, the League of Polish Families, a coalition partner in the Law and Justice government.[50] The proposition gained a lot of attention in the media and was widely condemned by the European Commission,[51] by Human Rights Watch[52] as well as by the Union of Polish Teachers, who organized a march through Warsaw (attended by 10,000 people) condemning the ministry's policy.[53][54] The bill was not voted on, and the government soon failed, leading to new parliamentary elections in which the League of Polish Families won no parliamentary seats.[55] Giertych retired from politics and returned to his work as an attorney.

Public opinion

In 2007, PBS conducted an opinion poll associated with Roman Giertych's speech at a meeting of EU education ministers in Heidelberg. The pollster asked respondents if they agreed with Minister Giertych's statements:[56]

- "Homosexual propaganda is growing in Europe, is reaching the younger children and is weakening the family." – 40% agreed, 56% disagreed.[56]

- "Homosexual propaganda needs to be limited, so children will not have an improper perspective on the family." – 56% agreed, 44% disagreed.[56]

- "Homosexuality is a deviation, we cannot promote as a normal relationship one between persons of the same sex in teaching young people, because objectively they are deviations from the natural law." – 44% agreed, 52% disagreed.[56]

Kaczyński's Presidential address

On 17 March 2008 Kaczyński delivered a presidential address to the nation on public television, in which he described gay marriage as an institution contrary to the widely accepted moral order in Poland and the moral beliefs of the majority of the population.[57] The address featured a wedding photograph of an Irish gay rights activist, Brendan Fay and Tom Moulton, which Kaczyński had not sought permission to use. The presidential address outraged left-wing political parties and gay rights activists, who subsequently invited the two to Poland and demanded apologies from the president, which he did not issue.

Jarosław Kaczyński

Lech's twin brother, Jarosław Kaczyński, who is the leader of Law and Justice and a former prime minister of Poland, has been less harsh in his descriptions of homosexuality. In one interview he stated that he had always been "in favour of tolerance" and that "the issue of intolerance towards gay people had never been a Polish problem". He said he did not recall gays being persecuted in the Polish People's Republic more severely than other minority groups and acknowledged that many eminent Polish celebrities and public figures of that era were widely known to be homosexual. Jarosław Kaczyński also remarked that there are a lot of gay clubs in Poland and that there is a substantial amount of gay press and literature.[58] In another interview abroad, he invited the interviewer to Warsaw to visit one of the many gay clubs in the capital. He also confirmed that there are some homosexuals in his own party, but said they would rather not open their private lives to the public. This was also confirmed by the Member of the European Parliament from PiS, Tadeusz Cymański.[59]

Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz

In a 2009 interview for Gazeta Wyborcza, former Polish Prime Minister Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz stated that his opinion about homosexual people changed when he met a Polish gay emigrant in London. The man stated that he "fled from Poland because he was gay and would not have freedom in his country". Marcinkiewicz concluded that he wouldn't want anyone to flee from Poland.[60]

Lech Wałęsa

In 2013, former President and Nobel prize winner Lech Wałęsa said that gay MPs should sit at the back of the parliament or even behind a wall and should not have important positions in Parliament. He also said that that pride parades should not take place in the city centres, but in the suburbs of cities. The former President also stated that minorities should not impose themselves upon the majority. Wałęsa could not have been accused of inciting to hatred because the Polish penal code doesn't include inciting to hatred against sexual orientation.[5][61][62]

LGBT movement

Parada Równości

The largest aspect of LGBT movement in Poland is the equality parade held in Warsaw every year since 2001.[63]

In 2004 and 2005 Warsaw officials denied permission to organize it, because of various reasons including the likelihood of counter-demonstrations, interference with religious or national holidays, and the lack of a permit.[64] Despite this, about 2,500 people marched illegally on 11 June 2005. Ten people were arrested. The ban has been declared illegal by the Bączkowski v Poland ruling of the European Court of Human Rights in 2007.[65]

The parade was condemned by the Mayor of Warsaw Lech Kaczyński, who said that allowing an official pride event in Warsaw would promote a homosexual lifestyle.[66]

The "Parada Równości" events have continued regularly since 2006, attracting crowds of less than 10,000 every year.[67]

Public opinion

The people of Warsaw are divided on the subject, but there was never a majority for the parade.[68] The most recent opinion poll, conducted by PBS for Gazeta Wyborcza, shows that 45% of Warsaw supports the parade.[68]

In 2005, 33% were for the organisation of the "Parada Równości", in 2008, that figure fell to 25%.[68]

Tęcza

The Warsaw rainbow is an artistic construction in the form of a giant rainbow made of artificial flowers, designed by Polish artist Julita Wójcik, located on St. Saviour Square in the Polish capital of Warsaw since summer 2012.

As the rainbow symbol is also associated with the LGBT movement, locating the Tęcza in the Savior Square in Warsaw has proved controversial.[69][70] It has been damaged five times as of November 2013, with the usual method of vandalism being arson.[71] The installation was damaged on 13 September 2012, 1 January 2013 (this one was ruled to be an accidental fireworks damage), 4 January 2013, July 2013 and once again during marches on Polish Independence Day on 11 November 2013.[71] The November 2013 incident occurred in the background of a wider demonstration by right-wing activists, who clashed with police and vandalized other parts of the city as well, also attacking the Warsaw's Russian embassy.[71]

The installation has been criticized by conservative and right-wing figures. Law and Justice politician Bartosz Kownacki derogatorily called the installation a "faggot rainbow" (pedalska tęcza).[69][72] Another Law and Justice politician, Stanisław Pięta, complained that this "hideous rainbow had hurt the feelings of believers" (attending the nearby Church of the Holiest Saviour).[73] Priest Tadeusz Rydzyk of Radio Maryja fame, described it as a "symbol of deviancy".[74]

Following the November 2013 incident, reconstruction of the Tęcza has garnered support from left-wing and liberal groups[71][73] President of Warsaw, Hanna Gronkiewicz-Waltz from the Civic Platform, declared that the installation "will be rebuilt as many times as necessary".[73][75] Several Polish celebrity figures have endorsed the installation, such as Edyta Górniak, Katarzyna Zielińska, Monika Olejnik and Michał Piróg; it has also been endorsed by the Swedish ambassador to Poland and LGBT activist Staffan Herrström.[71]

Public opinion

In a 2014 survey conducted by CBOS for Dr. Natalia Zimniewicz, 30% of Poles wanted a ban on public promotion of gay content, and 17.3% would not support that ban, but would want another form of limiting the freedom of promotion of such information.[76]

52.5% thought that the current scale of promotion of gay content is excessive, 27.9% thought that pictures of gay parades or practices disgust them, 22.3% think that the media blur the true image of homosexuality and 29.3% thought that gay content is not a private matter of the homosexual community, but have an impact on children and other citizens.[76]

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment only | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Same-sex marriages | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples | |

| Adoption by individuals | |

| Step-child adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Gays and lesbians allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood | |

See also

- Recognition of same-sex unions in Poland

- Human rights in Poland

- Politics of Poland

- Religion in Poland

- LGBT rights in Europe

References

- ↑ http://www2.hu-berlin.de/sexology/IES/poland.html%20%20 http://www2.hu-berlin.de/sexology/IES/poland.html

- ↑ The Oxford companion to politics of ... - Google Books. Google. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "Nie chcą krwi od gejów - Wiadomości i informacje z kraju - wydarzenia, komentarze - Dziennik.pl" (in Polish). Wiadomosci.dziennik.pl. Retrieved 2013-11-21.

- ↑ Tatchell (1992), p. 151

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Gera, Vanessa (3 March 2013). "Lech Walesa Shocks Poland With Anti-Gay Words". Huffington Post (Warsaw, Poland). AP. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ↑ Tatchell (1992), p. 151

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The Constitution of the Republic of Poland". Sejm. 2 April 1997. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ↑ "Sisco It". Bialystok.sa.sisco.info. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "Dziennik III RP: Nie ma wspólności, jest bezpodstawne wzbogacenie" (in Polish). Dziennik3rp.blogspot.com. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "Związek homoseksualny to nawet nie konkubinat" (in Polish). rp.pl. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ Precedensowy wyrok w Złotowie

- ↑ Strasbourg: Polish gays can inherit

- ↑ Mężczyzna walczy o prawo do mieszkania po zmarłym partnerze

- ↑ Sąd w Warszawie: Konkubinaty homo gorsze niż heteroseksualne

- ↑ "Poland :: Religion -- Encyclopedia Brittanica". Encyclopedia Brittanica. Encyclopedia Brittanica. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ↑ Boguszewski, Rafał (April 2012). "ZMIANY W ZAKRESIE WIARY I RELIGIJNOŚCI POLAKÓW PO ŚMIERCI JANA PAWŁA II" (PDF) (in Polish). CBOS. p. 5. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ↑ "Paweł Leszkowicz Wokół ratusza, czyli sztuka homoseksualna w polskiej przestrzeni publicznej." (in Polish). Nts.uni.wroc.pl. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "Draft Law on Equal Treatment 2007" (PDF). Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ Non-Discrimination Law: Poland Country Report 2010>

- ↑ "Ustawa o wdrożeniu niektórych przepisów Unii Europejskiej w zakresie równego traktowania" (PDF) (in Polish). Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ Sikora, Kamil. "Homoseksualizm w wojsku – największe tabu polskiej armii". Na Temat (in Polish). Na Temat. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ Boyes, Roger (25 May 2006). "Pilgrimage will let Pope pray for a country that is turning to intolerance". The Times Online. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ↑ http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb66/eb66_highlights_en.pdf

- ↑ Greenberg, Elizabeth. "EU Poll Shows Europeans Divided on Homosexual Marriage, but Reject Homosexual Adoptions.". Archived from the original on 11 July 2007.

- ↑ http://www.gaynz.com/aarticles/templates/features.asp?articleid=1871&zoneid=16

- ↑ Country Reports on Human Rights Practices in Poland, US Department of State

- ↑ "Poles against gay adoption – TheNews.pl :: News from Poland". Polskieradio.pl. 26 May 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ mar. "Premier-gej? Polacy nie mają nic przeciwko temu" (in Polish). Wiadomosci.gazeta.pl. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ ""Nie" dla małżeństw gejowskich" (in Polish). rp.pl. 23 March 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "Sondaż: Geje w wojsku dzielą Polaków". Newsweek (in Polish). Newsweek. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ "Polacy nie chcą parad homoseksualistów - Polska - Fakty w INTERIA.PL" (in Polish). Fakty.interia.pl. 6 June 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ Renata Grochal (2011-05-31). "Gej przestraszył Platformę" (in Polish). M.wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 2013-11-21.

- ↑ Feliksiak, Michał (February 2013). "Stosunek do praw gejów i lesbijek oraz związków partnerskich" (PDF) (in Polish). Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ CBOS: Jesteśmy za wychowywaniem dzieci przez pary homoseksualne [...]. M.wyborcza.pl (14 November 2014). Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ↑ "POSTAWY WOBEC MAŁŻEŃSTW HOMOSEKSUALISTÓW" (PDF) (in Polish). CENTRUM BADANIA OPINII SPOŁECZNEJ. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ↑ "KONKUBINAT PAR HETEROSEKSUALNYCH I HOMOSEKSUALNYCH" (PDF) (in Polish). CENTRUM BADANIA OPINII SPOŁECZNEJ. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ↑ "ZWIĄZKI PARTNERSKIE PAR HOMOSEKSUALNYCH" (PDF) (in Polish). CENTRUM BADANIA OPINII SPOŁECZNEJ. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ↑ "AKCEPTACJA PRAW DLA GEJÓW I LESBIJEK I SPOŁECZNY DYSTANS WOBEC NICH" (PDF) (in Polish). CENTRUM BADANIA OPINII SPOŁECZNEJ. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ↑ Wenzel, Michał. "PRAWA GEJÓW I LESBIJEK" (PDF) (in Polish). CENTRUM BADANIA OPINII SPOŁECZNEJ. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ↑ "PRAWA GEJÓW I LESBIJEK" (PDF) (in Polish). CENTRUM BADANIA OPINII SPOŁECZNEJ. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ↑ "Polacy: Związki partnerskie nie dla gejów" (in Polish). M.wyborcza.pl/. 2013-02-28. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ↑ "STOSUNEK DO PRAW GEJÓW I LESBIJEK ORAZ ZWIĄZKÓW PARTNERSKICH" (PDF) (in Polish). CENTRUM BADANIA OPINII SPOŁECZNEJ. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ↑ Związki partnerskie – za czy przeciw?.

- ↑ Polski rekord tolerancji: 40 proc. z nas akceptuje związki partnerskie dla homoseksualistów. M.wyborcza.pl (9 October 2013). Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ Gej przestraszył Platformę. M.wyborcza.pl (31 May 2011). Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ TNS Polska: 67 proc. za prawami związków partnerskich heteroseksualnych.

- ↑ Sondaż Super Expressu o związkach partnerskich: Polacy przeciw małżeństwom homo!. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ Równe traktowanie standardem dobrego rządzenia. (pages 36–39).

- ↑ Wenzel, Michał (2005). "AKCEPTACJA PRAW DLA GEJÓW I LESBIJEK I SPOŁECZNY DYSTANS WOBEC NICH" (PDF) (in Polish). CBOS. p. 8. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Ireland, Doug (21 March 2007). "DIRELAND: POLAND'S SWEEPING NEW ANTI-GAY EDUCATION BILL". Direland. Direland. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ↑ Scott Long Director, LGBT Rights Program (2007-03-19). "Poland: School Censorship Proposal Threatens Basic Rights | Human Rights Watch". Hrw.org. Retrieved 2013-11-21.

- ↑ "Poland to ban discussion of homosexuality in schools". Avert. Avert. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ↑ "Polish teachers march in Warsaw". BBC News. 17 March 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ "Polish 'anti-gay' bill criticised". BBC News. 19 March 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ "Opposition prevails in Polish election". The Daily Telegraph (London). 22 October 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 "Wystąpienie min. Giertycha na spotkaniu ministrów edukacji państw UE" (in Polish). PBS. 2 March 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ↑ "Orędzie Lecha Kaczyńskiego 17.03.2008" (in Polish). YouTube. 17 March 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ ">< Artykuł >". < Gaylife.Pl. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑

- ↑ Graham, Colin (1 July 2007). "Gay Poles head for UK to escape state crackdown". London: The Observer. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

- ↑ "Walesa escapes hate crime charge after anti-gay tirade". Polskie Radio dla Zagranicy. 13 March 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ↑ "Poland: Lech Walesa – 'Gays should be made to sit at the back in parliament'". Thenews.pl. ILGA Europe. 4 March 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ↑ ""Parada Równości" to propaganda rozpusty". Gość Niedzielny (in Polish). Katolicka Agencja Informacyjna (KAI). 10 August 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ Townley, Ben (20 May 2005). "Polish capital bans Pride again". Gay,com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007.

- ↑ (kaka) (2007-05-04). "News from Poland - Polish gay activists win human rights case". Web.archive.org. Retrieved 2014-05-07.

- ↑ Gay marchers ignore ban in Warsaw, BBC News Online, 11 June 2005

- ↑ "A brief history of Equality Parade | Equality Parade". En.paradarownosci.eu. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 Dubrowska, Magdalena (9 January 2010). "Europride - test dla warszawiaków". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Kalocińska, Anna (12 November 2013). "Julita Wójcik, autorka "Tęczy": Tęcza, zwłaszcza ta spalona, ma być symbolem opamiętania". wp.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ Halicki, Piotr (13 November 2013). "Jest reakcja właściciela tęczy. "Agresja żuli"". Onet (in Polish) (Warsaw, Poland). Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 71.3 71.4 Sowa, Agnieszka (19 November 2013). "Polityczna historia tęczy z Placu Zbawiciela: Tęcza na miarę naszych możliwości". Polityka (in Polish). Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ Przybyszewski, R (15 November 2013). ""PEDALSKA TĘCZA". KOWNACKI PODTRZYMUJE SWOJE SŁOWA". TVP Regionalna (in Polish). Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 N., L. (18 November 2013). "Poland: Burning the rainbow". The Economist (Poland). Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ "Rydzyk o tęczy: Symbole zboczeń nie powinny być tolerowane". Fakt (in Polish). wyborcza.pl. 14 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ "Odbudują tęczę. "Ile razy trzeba będzie, tyle razy będziemy"". TVN Warszawa (in Polish). TVN. 12 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 "Połowa Polaków chce zakazu promocji treści gejowskich [badanie]". MaR (in Polish). fronda.pl. 18 August 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ↑ http://wyborcza.pl/1,76842,13622028,Prof__Letowska__Konstytucja_nie_zakazuje_zwiazkow.html

- ↑ http://weekend.gazeta.pl/weekend/1,138262,17717506,Osobom_homoseksualnym_oferuje_sie_obchodzenie_prawa_.html#TRwknd

- ↑ http://www.mpips.gov.pl/gfx/mpips/userfiles/_public/1_NOWA%20STRONA/Polityka%20rodzinna/adopcja/broszura%20-%20ADOPCJE.pdf

- ↑ http://www.waszyngton.msz.gov.pl/pl/waszyngton_us_a_pl_informacje_konsularne/waszyngton_us_a_pl_sprawy_prawne/waszyngton_us_a_pl_przysposobienie_maloletnich/?printMode=true

Bibliography

Tatchell, Peter. (1992). Europe in the pink: lesbian & gay equality in the new Europe. GMP. ISBN 978-0-85449-158-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LGBT in Poland. |

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights in Poland and Latvia, Amnesty International, 15 November 2006

- Situation of bisexual and homosexual persons in Poland. 2005 and 2006 report. – Campaign Against Homophobia, ISBN 978-83-924950-2-4, Warsaw 2007

| ||||||||||||||||||