Kronosaurus

| Kronosaurus Temporal range: 125–99Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| K. boyacensis in Villa de Leyva, Boyaca, Colombia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Sauropsida |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pliosauroidea |

| Family: | †Pliosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Brachaucheninae |

| Genus: | †Kronosaurus Longman, 1924[1] |

| Species | |

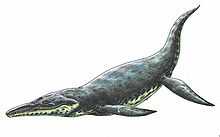

Kronosaurus (/ˌkrɒnoʊˈsɔrəs/ KRON-o-SAWR-əs; meaning "lizard of Kronos") is an extinct genus of short-necked pliosaur. It was among the largest pliosaurs, and is named after the leader of the Greek Titans, Cronus. It lived in the Early Cretaceous Period (Aptian-Albian).[2][3]

Discovery and species

In 1899, Andrew Crombie of Hughenden discovered a "scrap of bone" containing six conical teeth, and gave this fragmentary fossil to the Queensland Museum. Twenty-five years later, then-director Heber Longman formally described the specimen as the holotype of a new species: Kronosaurus queenslandicus.[1][4] More Kronosaurus material, including a partial skull, was discovered in 1929, in the same location as Crombie's original find.[4]

While touring Australia in 1932, a fossil-hunting expedition from Harvard University led by William E. Schevill was told of some interesting rocks on some property near Hughenden.[4] The rocks were limestone nodules containing the most complete skeleton of Kronosaurus ever discovered.[4][5] After dynamiting the nodules out of the ground (and into smaller pieces), Scheville had them shipped back to Harvard for examination and preparation. The skull—which matched the holotype jaw fragment of K. queenslandicus—was prepared right away, but time and budget constraints put off restoration of the nearly complete skeleton for 20 years.[5] The restored and mounted skeleton was displayed at Harvard in 1959.[4][5]

In 1977, a Colombian peasant farmer from Moniquirá turned up an enormous stone while tilling his field, which he later recognized as a possible fossil. Excavation revealed a nearly complete Kronosaurus skeleton, one of the best preserved fossils to come from Colombia.[6] Oliver Hampe formally described the specimen in 1992, assigning it to a second species, K. boyacensis.[2]

The people of Villa de Leyva built a museum, El Fósil, around the spot where the skeleton was excavated, and the K. boyacensis skeleton is currently on display there.[6]

Description

Like other pliosaurs, Kronosaurus was a marine reptile. It had an elongated head, a short neck, a stiff body propelled by four flippers, and a relatively short tail. The posterior flippers were larger than the anterior. Kronosaurus was carnivorous, and had many long, sharp, conical teeth. Current estimates put Kronosaurus at around 9–10 meters (30–33 feet) in length.[3]

All Sauropterygians had a modified pectoral girdle that supported a powerful swimming stroke.[7] Kronosaurus and other plesiosaurs/pliosaurs had a similarly adapted pelvic girdle,[8] allowing them to push hard against the water with all four flippers. Between its two limb girdles was a massive mesh of gastralia (belly ribs) that provided additional strength and support.[8] The strength of the limb girdles, combined with evidence of large, powerful swimming muscles, indicates that Kronosaurus was likely a fast, active swimmer.[8]

Size issues

Body-length estimates, largely based on the 1959 Harvard reconstruction, had previously put the total length of Kronosaurus at 12.8 meters (43 feet).[9] However, a recent study comparing fossil specimens of Kronosaurus to other pliosaurs suggests that the Harvard reconstruction may have included too many vertebrae, exaggerating the previous estimate, with the true length probably only 9–10 meters (30–33 feet).[3]

Teeth

Kronosaurus teeth exceed 7 cm in length (the largest up to 30 cm long with 12 cm crowns). However, they lack carinae (cutting edges) and the distinct trihedral (three facets) of Pliosaurus and Liopleurodon teeth. The combination of large size, conical shape and lack of cutting edges allows for easy identification of Kronosaurus teeth in Cretaceous deposits from Australia.[3][10]

Habitat

Kronosaurus is known from Australia and Colombia. Both areas were covered by shallow inland seas when Kronosaurus inhabited them.[6][11]

Diet

Fossil stomach contents from Northern Queensland show that Kronosaurus preyed on turtles and plesiosaurs. Fossil remains of giant squid have been found in the same area as Kronosaurus; it may have fed on them, but no direct evidence for this exists.[11]

Large, round bite-marks have been found on the skull of an Albian-age Australian elasmosaurid (Eromangasaurus) that could be from a Kronosaurus attack.[12][13]

Classification

The cladogram below follows a 2011 analysis by paleontologists Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson, and reduced to genera only.[14]

| Pliosauroidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Longman HA. 1924. A new gigantic marine reptile from the Queensland Cretaceous, Kronosaurus queenslandicus new genus and species. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 8: 26–28.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Hampe O. 1992. Ein großwüchsiger Pliosauride (Reptilia: Plesiosauria) aus der Unterkreide (oberes Aptium) von Kolumbien. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 145: 1-32.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Kear BP. 2003. Cretaceous marine reptiles of Australia: a review of taxonomy and distribution. Cretaceous Research 24: 277–303.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Mather, Patricia, with Agnew, N.H. et al. The History of the Queensland Museum, 1862-1986 Retrieved from archive.org

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Meyers, Troy. Kronosaurus Chronicles. Australian Age of Dinosaurs, Issue 3, 2005. Retrieved from australianageofdinosaurs.com

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 http://museoelfosil.com/

- ↑ http://palaeos.com/vertebrates/sauropterygia/sauropterygia.html

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 http://palaeos.com/vertebrates/sauropterygia/plesiosauria2.html

- ↑ Romer AS, Lewis AD. 1959. A mounted skeleton of the giant plesiosaur Kronosaurus. Breviora 112: 1-15.

- ↑ Massare JA. 1997. Introduction - faunas, behaviour and evolution. In: Callaway JM, Nicholls EL. (Eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles. Academic Press, San Diego, pp. 401-421.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 http://www.qm.qld.gov.au/Find+out+about/Dinosaurs+and+Ancient+Life+of+Queensland/Dinosaurs/Giant+marine+reptiles/Kronosaurus

- ↑ Sachs S. 2005. Tuarangisaurus australis sp. nov. (Plesiosauria: Elasmosauridae) from the Lower Cretaceous of northeastern Queensland, with additional notes on the phylogeny of the Elasmosauridae. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 50 (2): 425-440.

- ↑ Kear, B. P. 2007. Taxonomic Clarification of the Australian Elasmosaurid Genus Eromangasaurus, with Reference to Other Austral Elasmosaur Taxa. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 27 (1): 241-246.

- ↑ Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson (2011). "A new pliosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Oxford Clay Formation (Middle Jurassic, Callovian) of England: evidence for a gracile, longirostrine grade of Early-Middle Jurassic pliosaurids". Special Papers in Palaeontology 86: 109–129. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01083.x.

- ↑ Schumacher, B. A.; Carpenter, K.; Everhart, M. J. (2013). "A new Cretaceous Pliosaurid (Reptilia, Plesiosauria) from the Carlile Shale (middle Turonian) of Russell County, Kansas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33 (3): 613. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.722576.

External links

- Genus Kronosaurus. The Plesiosaur Directory.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||