Kosovo Albanians

| |||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 million | |||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||

| 1,616,869 (2011)[1] | |||||||||||||||||

| 300,000[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 200,000[2][3][4] | |||||||||||||||||

| 43,751[5] | |||||||||||||||||

| 21,371[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 19,576[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 13,452[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 12,359[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 10,643[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 7,891[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 6,783[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| Rest of the World | 39,535–100,000[2] | ||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||

|

Albanian (Gheg dialect) | |||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||

|

Majority Sunni Muslim Roman Catholic, Bektashi, Protestant and Atheist minorities. | |||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||

| Albanians | |||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Kosovo Albanians |

|---|

|

| Kosovo culture |

|

Art · Cinema · Dress · Literature · Music Sport · Cuisine · Mythology |

| By region or country |

|

Kosovo · Australia · Bulgaria Croatia · Germany Greece · Italy Kosovo · Macedonia Montenegro · Romania Serbia · Sweden Switzerland · Ukraine · United States |

| Varieties of Albanian |

|

Gheg · Tosk · Arvanitika Arbëresh · Cham |

| Religion |

|

Islam in Kosovo Christianity in Kosovo Roman Catholicism Kosovo Protestant Evangelical Church |

| History |

| Origins · History |

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| Nation |

| Communities |

|

| Subgroups |

| Albanian culture |

| Albanian language |

|

|

| Religion |

| History |

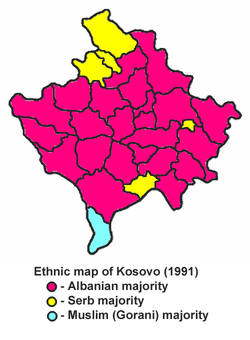

Albanians are the largest ethnic group in Kosovo[a], commonly called Kosovar, Kosovan or Kosovo Albanians. According to the 1991 Yugoslav census, boycotted by Albanians, there were 1,596,072 ethnic Albanians in Kosovo or 81.6% of population. By the estimation in year 2000, there were between 1,584,000 and 1,733,600 Albanians in Kosovo or 88% of population; as of today their population is 92,93%. Albanians of Kosovo are Ghegs.[6] They speak Gheg Albanian, more specifically the Northern and Northeastern Gheg variants.

Kosovar Albanians are ethnic Albanians with ancestry or descent in the region, regardless of whether they live in Kosovo. A large Kosovar Albanian diaspora has formed since the Kosovo War, mostly in Germany and Switzerland. An estimated 500,000 Kosovar Albanians live in either Switzerland or Germany (about 300,000 in Germany and 200,000 in Switzerland), accounting for roughly one fifth of the total number of Kosovar Albanians.

History

.jpg)

Before World War I

Albanian presence in Kosovo is recorded since the medieval period. The Albanian ethnic identity of the larger parts of Albanian-speaking population and other ethnic groups did not yet exist in Kosovo during the late Ottoman period.[8] As the Serbs expelled a large number of Albanians from the regions of Niš, Pirot, Leskovac and Vranje in southern Serbia, which the Congress of Berlin of 1878 had given to the Belgrade Principality, a large number of them settled in Kosovo, where they are known as muhaxher (meaning the exiled, from the Arabic muhajir) and whose descendants often bear the surname Muhaxheri.

As a reaction against the Congress of Berlin, which had given some Albanian-populated territories to Serbia and Montenegro, Albanians, mostly from Kosovo, formed the League of Prizren in Prizren in June 1878. Hundreds of Albanian leaders gathered in Prizren and opposed the Serbian and Montenegrin jurisdiction. Serbia complained to the Western Powers that the promised territories were not being held because the Ottomans were hesitating to do that. Western Powers put pressure to the Ottomans and in 1881, the Ottoman Army started the fighting against Albanians. The Prizren League created a Provisional Government with a President, Prime Minister (Ymer Prizreni) and Ministries of War (Sylejman Vokshi) and Foreign Ministry (Abdyl Frashëri). After three years of war, the Albanians were defeated. Many of the leaders were executed and imprisoned. In 1910, an Albanian uprising spread from Pristina and lasted until the Ottoman Sultan's visit to Kosovo in June 1911. The aim of the League of Prizren was to unite the four Albanian-inhabited Vilayets by merging the majority of Albanian inhabitants within the Ottoman Empire into one Albanian vilayet. However at that time Serbs consisted about 25%[9] of the whole Vilayet of Kosovo's overall population and were opposing the Albanian aims along with Turks and other Slavs in Kosovo, which prevented the Albanian movements from establishing their rule over Kosovo.

World Wars era

In 1912 during the Balkan Wars, most of Eastern Kosovo was taken by the Kingdom of Serbia, while the Kingdom of Montenegro took Western Kosovo, which a majority of its inhabitants call "The Plateau of Dukagjin" (Rrafsh i Dukagjinit) and the Serbs call Metohija (Метохија), a Greek word meant for the landed dependencies of a monastery. Colonist Serb families moved into Kosovo, while the Albanian population was decreased. As a result, the proportion of Albanians in Kosovo declined from 75 percent[9][10] at the time of the invasion to slightly more than 65%[10] percent by 1941.

The 1918–1929 period under the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was a time of persecution of the Kosovar Albanians. Kosovo was split into four counties—three being a part of official Serbia: Zvečan, Kosovo and southern Metohija; and one in Montenegro: northern Metohija. However, the new administration system since 26 April 1922 split Kosovo among three Regions in the Kingdom: Kosovo, Rascia and Zeta.

In 1929 the Kingdom was transformed into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The territories of Kosovo were split among the Banate of Zeta, the Banate of Morava and the Banate of Vardar. The Kingdom lasted until the World War II Axis invasion of April 1941.

After the Axis invasion, the greater part of Kosovo became a part of Italian-controlled Fascist Albania, and a smaller, Eastern part by the Nazi-Fascist Tsardom of Bulgaria and Nazi German-occupied Kingdom of Serbia. Since the Albanian Fascist political leadership had decided in the Conference of Bujan that Kosovo would remain a part of Albania they started expelling the Serbian and Montenegrin settlers "who had arrived in the 1920s and 1930s".[11] Prior to the surrender of Fascist Italy in 1943, the German forces took over direct control of the region. After numerous Serbian and Yugoslav Partisans uprisings, Kosovo was liberated after 1944 with the help of the Albanian partisans of the Comintern, and became a province of Serbia within the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia.

Within Yugoslavia

The Province of Kosovo and Metohija was formed in 1946 as an autonomous region to placate its regional Albanian population within the People's Republic of Serbia as a member of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia under the leadership of the former Partisan leader, Josip Broz Tito, but with no factual autonomy. This was the first time Kosovo came to exist with its present boundaries. After the Yugoslavia's name changed to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Serbia's to the Socialist Republic of Serbia in 1953, the Autonomous Region of Kosovo and gained inner autonomy in the 1960s.

In the 1974 constitution, the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo's government received higher powers, including the highest governmental titles—President and Premier and a seat in the Federal Presidency, which made it a de facto Socialist Republic within the Federation, but remaining as a Socialist Autonomous Region within the Socialist Republic of Serbia. Serbo-Croat and Albanian were defined official on the provincial level marking the two largest linguistic Kosovan groups: Serbs and Albanians. The word Metohija was also removed from the title in 1974 leaving the simple short form, Kosovo.

In the 1970s, an Albanian nationalist movement pursued full recognition of the Province of Kosovo as another Republic within the Federation, while the most extreme elements aimed for full-scale independence. Tito's government dealt with the situation swiftly, but only giving it a temporary solution.

In 1981 the Kosovar Albanian students organised protests seeking that Kosovo become a republic within Yugoslavia. Those protests were harshly contained by the centralist Yugoslav government. In 1986, the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) was working on a document, which later would be known as the SANU Memorandum. An unfinished edition was filtered to the press. In the essay, SANU portrayed the Serbian people as a victim and called for the revival of Serb nationalism, using both true and exaggerated facts for propaganda. During this time, Slobodan Milošević rose to power in the League of the Socialists of Serbia.

Soon afterwards, as approved by the Assembly in 1990, the autonomy of Kosovo was revoked, and the pre-1974 status reinstated. Milošević, however, did not remove Kosovo's seat from the Federal Presidency, but he installed his own supporters in that seat, so he could gain power in the Federal government. After Slovenia's secession from Yugoslavia in 1991, Milošević used the seat to obtain dominance over the Federal government, outvoting his opponents.

Many Albanians organized a peaceful active resistance movement, following the job losses suffered by some of them, while other, more radical and nationalistic oriented Albanians, started violent purges of the non-Albanian residents of Kosovo.

On July 2, 1990, an unconstitutional Albanian parliament declared Kosovo an independent country, although this was not recognized by the Government since the Albanians refused to register themselves as legal citizens of Yugoslavia. In September of that year, the Albanian parliament, meeting in secrecy in the town of Kačanik, adopted the Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo. Two years later, in 1992, the Parliament organized a referendum, which was observed by international organisations, but was not recognized internationally because of a lot of irregularities. With an 80% turnout, 98% voted for Kosovo to be independent. The non-Albanian population refused to vote since they considered the referendum to be illegal. In the early nineties, Albanians organised a parallel state system and a parallel system of education and healthcare, among other things, Albanians organized and trained, with the help of some European countries, the army of the self-declared Kosovo republic called the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). With the events in Bosnia and Croatia coming to an end, the Yugoslav government started relocating Serbian refugees from Croatia and Bosnia to Kosovo. The OVK managed to re-relocate Serbian refugees back to Serbia..

Kosovo War

After the Dayton Agreement in 1995, a guerilla force calling itself the Kosovo Liberation Army, started to operate in Kosovo, although there are speculations that they may have started as early as 1992. Serbian paramilitary forces committed war crimes in Kosovo, although the Serbian government claims that the army was only going after suspected Albanian terrorists. This triggered a 78-day NATO campaign in 1999. The Albanian Kosovar KLA played a major role not only in reconnaissance missions for the NATO, but in sabotaging of the Serbian Army as well.

International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo, as envisaged under UN Security Council Resolution 1244, which ended the Kosovo conflict of 1999. While Serbia's continued sovereignty over Kosovo is recognised by much of the international community, a clear majority of Kosovo's population prefers independence. The UN-backed talks, led by UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, began in February 2006. While progress was made on technical matters, both parties remained diametrically opposed on the question of status itself.[12] In February 2007, Ahtisaari delivered a draft status settlement proposal to leaders in Belgrade and Pristina, the basis for a draft UN Security Council Resolution that proposes 'supervised independence' for the province. As of early July 2007 the draft resolution, which is backed by the United States, United Kingdom and other European members of the United Nations Security Council, had been rewritten four times to try to accommodate Russian concerns that such a resolution would undermine the principle of state sovereignty.[13] Russia, which holds a veto in the Security Council as one of five permanent members, has stated that it will not support any resolution that is not acceptable to both Belgrade and Pristina.[14]

Culture

The most widespread religion among Albanians in Kosovo is Islam (mostly Sunni. The other religion Kosovar Albanians practice is Roman Catholicism). Culturally, Albanians in Kosovo are very closely related to Albanians in Albania. Traditions and customs differ even from town to town in Kosovo itself. The spoken dialect is Gheg, typical of northern Albanians. The language of state institutions, education, books, media and newspapers is the standard dialect of Albanian, which is closer to the Tosk dialect.

Education is provided for all levels, primary, secondary, and university degrees. University of Pristina is the public university of Kosovo, with several faculties and majors. The National Library (Alb: Bibloteka Kombëtare) is the main and the largest library in Kosovo, located in the centre of Pristina. There are many other private universities, among them American University in Kosovo (AUK), etc., and many secondary schools and colleges such as Mehmet Akif College.

Kosovafilmi is the film industry, which releases movies in Albanian, created by Kosovar Albanian movie-makers.

The National Theatre of Kosovo (Alb: Teatri Kombëtar i Kosovës) is the main theatre where plays are shown regularly by Albanian and international artists.

Music

Music has always been part of Albanian culture. Although in Kosovo music is diverse (as it was mixed with the cultures of different regimes dominating Kosovo), authentic Albanian music does still exist. It is characterized by use of çiftelia (an authentic Albanian instrument), mandolina, mandola and percussion.

Folk music is very popular in Kosovo. There are many folk singers and ensembles.

Modern music in Kosovo has its origin from western countries. The main modern genres include Pop, Hip Hop/Rap, Rock, and Jazz. The most notable rock bands are: Gjurmët, Troja, Votra, Diadema, Humus, Asgjë sikur Dielli, Kthjellu, Gillespie, Cute Babulja, Babilon etc. Ilir Bajri is a notable jazz and electronic musician.

There are some notable music festivals in Kosovo:

- Rock për Rock includes rock and metal music

- Polifest includes all kinds of genres (usually hip hop, commercial pop, and never rock or metal)

- Showfest includes all kinds of genres (usually hip hop, commercial pop, unusually rock and never metal)

- Videofest includes all kinds of genres

Kosovo Radiotelevisions like RTK, 21 and KTV have their musical charts.

Prominent people

Before 1950

- Andrea Bogdani (c. 1600 – 1683), Catholic prelate and Archbishop of Skopje

- Llukë Bogdani (16??–1687), poet

- Pjetër Bogdani, (1630–1689), Catholic prelate, Archbishop of Skopje and author of Cuneus Prophetarum, considered to be the most prominent work of early Albanian literature

- Toma Raspasani, (1648–17??), Franciscan monk and vicar of Pjetër Bogdani

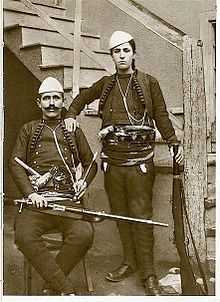

- Isa Boletini (1864–1916), leader of the Albanian anti-Ottoman revolts of the late 19th and early 20th century

- Bajram Curri (1862–1925), minister of defence of Albania and member of the Committee for the National Defence of Kosovo

- Nexhip Draga (1867–1920), deputy of the Ottoman and later of the Yugoslav parliament

- Azem Galica (1889–1924), anti-Yugoslav rebel of the pre-World War II era

- Shota Galica (1895–1927), anti-Yugoslav rebel of the pre-World War II era and wife of Azem Galica

- Shtjefën Gjeçovi, (1873–1929), Catholic priest, ethnologist and folklorist

- Pjetër Mazreku, Catholic prelate, Archbishop of Bar and Bishop of Prizren

- Shaban Polluzha, anti-Communist military leader

- Hasan Prishtina (1873–1933) born in Vučitrn, former Albanian Prime Minister, and organizer of Albanian movements against Ottomans and other regimes installed in Kosovo, during the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century

- Ymer Prizreni (1820–1887), founding member and leader of the League of Prizren

- Sulejman Vokshi (1815–1890), leader of the military branch of the League of Prizren

Current

- Sinan Hasani, president of Yugoslavia (1986–1987)

- Nexhmije Pagarusha, born on May 7, 1933, singer and actress

- Ibrahim Rugova former President of Kosovo and founder and head of Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK) and organizer of the peaceful resistance of Kosovar Albanians, 1990–1999 (died of lung cancer on Jan 21, 2006)

- Adem Jashari, (1955–1998), born in Prekaz, a distinguished commander of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), killed during the 1999 Kosovo War

- Arta Dobroshi, born in Pristina, European Academy Award Nominated Actor

- Sislej Xhafa Contemporary Artist

- Fatmir Sejdiu first president of Republic of Kosovo, formerly the political leader of the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK)

- Veton Surroi former publicist of Koha Ditore, formerly the political leader of the ORA reformist party

- Nexhat Daci PhD in Chemistry, university professor, and former speaker of Assembly of Kosovo; s former member of the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), he is now the leader of the Democratic League of Dardania (LDD)

- Agim Çeku former Colonel of the Croatian Army, former military commander of Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and later of the Kosovo Protection Corps (KPC), former Prime Minister of Kosovo

- Rifat Kukaj (25 October 1938 – September 11, 2005), one of the most successful writers in Albanian literature for children, born in Tërstenik, Drenica, region of Kosovo

- Anton Çetta, born in Gjakova, Albanian Kosovar patriot, folklorist, academician, university professor, the founder of the Reconciliation Committee for erasing blood feuds in Kosovo (Alb: Komiteti per pajtimin e gjaqeve ne Kosovë), famous for having settled almost all of blood feuds among Albanians in Kosovo in the 1990s

- Albin Kurti, a former leader of the student protests during the late 1990s, currently the leader of the VETËVENDOSJE! (Self-determination) movement, which fights for the right of Albanians in Kosovo for self-determination on the future of Kosovo

- Ahmet Haxhiu, political activist notable for involvement with People's Movement of Kosovo and Kosovo Liberation Army

- Albulena Haxhiu, politician

- Adnan Januzaj, football player

- Xhevad Prekazi, football player

- Shefki Kuqi, football player

- Marigona Dragusha, model, Miss Universe 2009 runner-up

- Rita Ora, singer-songwriter

- Benet Kaci, television personality

- Kosovare Asllani, football player for Sweden

- Xherdan Shaqiri, football player

See also

- Albanians

- Kosovo

- Albanians in Macedonia

- Albanians in Montenegro

- Kosovan diaspora

- Demographic history of Kosovo

Notes

| a. | ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Serbia and the Republic of Kosovo. The latter declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. Kosovo's independence has been recognised by 108 out of 193 United Nations member states. |

References

- ↑ "Minority Communities in the 2011 Kosovo Census Results: Analysis and Recommendations" (PDF). European Centre for Minority Issues Kosovo. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 "Emigration in Kosovo (International Emigation) - Page 32-38". Kosovo Agency of Statistics, KAS.

- ↑ "Die kosovarische Bevölkerung in der Schweiz" (PDF).

- ↑ "Donner une autre image de la diaspora kosovare".

- ↑ "Kosovari in Italia".

- ↑ Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo (1999). World music: the rough guide. Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Rough Guides. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

Most of the ethnic Albanians that live outside the country are Ghegs, although there is a small Tosk population clustered around the shores of lakes Presp and Ohrid in the south of Macedonia.

- ↑ Robert Shannan Peckham, Map mania: nationalism and the politics of place in Greece, 1870–1922, Political Geography, 2000, p.4: "Other maps by among others the Frenchman F. Bianconi [1877], who was the chief architect and engineer of the Ottoman railways, A. Synvet [1877] and Karl Sax [1878], a former Austrian consul in Andrianople, were similarly favourable to the Greek cause."

- ↑ Hannes Grandits; Nathalie Clayer; Robert Pichler (15 May 2011), Conflicting Loyalties in the Balkans: The Great Powers, the Ottoman Empire and Nation-Building, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-1-84885-477-2

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Malcolm, Noel (2008-02-26). "Is Kosovo Serbia? We ask a historian". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 http://www.seep.ceu.hu/archives/issue61/herbert.pdf

- ↑ The Emerging Strategic Environment: Challenges of the Twenty-First Century - Google Boeken

- ↑ "UN frustrated by Kosovo deadlock", BBC News, October 9, 2006.

- ↑ Russia reportedly rejects fourth draft resolution on Kosovo status (SETimes.com)

- ↑ UN Security Council remains divided on Kosovo (SETimes.com)

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

.jpg)