Kintampo Complex

Kintampo complex describes a period in prehistory that saw the transition to sedentism in West Africa, specifically Ghana and parts of eastern Côte d'Ivoire that began sometime between 2500-1400 BCE. When referring to topics related to Kintampo, the term complex is preferred as opposed to culture. In an archaeological research context, culture implies that every site represented in the area used the same technologies and techniques to create the same types of tools, goods, and foods, had the same beliefs and customs, and so on. In reality, the inhabitants of the region during this particular period of time did have much in common, but did differ enough from village to village that culture is not entirely accurate. Complex, or sometimes tradition on the other hand, is a term that can be applied more widely (and perhaps more vaguely) to mean a group that shares many characteristics, but also acknowledges differences. The name Kintampo which is used to describe the complex comes from the Kintampo district in the Brong-Ahafo region of Ghana.

Besides being a classic example of early forest dwellers in west Africa, Kintampo is significant because there is evidence of a drastic change in food production techniques due to the transition from nomadic hunter-gather lifestyles to life in stationary settlements. This change is known as sedentism and is typical of societies who have access to, or are developing systems of agriculture. Ceramic sculptures of humans and animals indicate that the Kintampo settlements were lived at by practitioners of both pastoralism and horticulture.

Another notable aspect of the Kintampo complex is the creation of art and items of personal adornment. Archaeologists have found polished stone beads, bracelets and figurines in addition to typical stone tools and structures such as hand axes, and building foundations which suggests that these people had both a complex society and were well-learned in Later Stone Age technologies.[1]

Settlement of West Africa

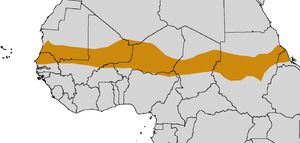

During the Middle Stone Age, technological advancements allowed humans originating in East Africa to adapt to new and diverse areas and allowed them to spread out and settle most of the African continent. Another motivator for the East African exodus was the expanding population that was growing exponentially. It was also during this era that humans are thought to have first traveled out of Africa; to Southwest Asia (also known as the Middle East), Asia and to Southeast Europe by traveling across the Sinai Peninsula and land bridges across the Red Sea, and to Western Europe by crossing at Gibraltar. Indeed, by the 10th millennium BC, there was substantial occupation of the upper part of Africa including large populations in what was then a region of lush forest: the Sahara.[2]

After the end of the last ice age, the geography and climate of the Sahara region began to change drastically. The northern part dried out due to the Earth tilting on its axis allowing the region to absorb more solar radiation, thus a desert was formed.[3] The area directly to the south became a humid monsoon region, receiving massive amounts of precipitation due to moisture drawn in from the oceans. By the late 5th millennium BC, the planet had tilted even more on its axis and consequently the desert had spread southward, making previously settled areas unlivable.[4] People began traveling further south, away from the Sahara, some settling in the fringes of the desert, an area known today as the Sahel, a unique type of landscape that forms a buffer zone between desert and savannahs and forests (by this point in time, the Sahara had expanded to approximately the same extent as is today). Other kept traveling south, finding themselves in the humid rainforests of West Africa.[2] These are thought to be the people who founded the Kintampo way of life.

There is another theory that states that instead of a mass migration from the Sahel of people who formed the Kintampo complex, it was formed by local Punpun foragers through interaction with peoples to the north. As the Punpun, who had long lived in the area, adopted the new traits, they ceased to be hunter gatherers, and adapted sedentism and horticulture. There is much speculation by Africanists as to whether or not the Kintampo tradition evolved from Punpun, but it appears that the two existed simultaneously for some time.[5]

- See also: Neolithic Subpluvial

Sites

Archaeologists have identified studied at least three dozen sites relating to the Kintampo complex in three different types of environments within and near Ghana.[6]

Northern savanna

- Birimi This site was found in 1987 by Francois Kense. There is evidence of pearl millet having been cultivated.[7]

- Chukoto

- Daboya At this site, pieces of charred pearl millet were found. Also found, were structural remains from housing, burnished pottery, beads made from various materials, including quartz and shell.

- Lake Kpriri

- Mole Game Reserve

- Ntereso Found in 1952 by Oliver Davies, outlines of dwellings have been excavated since the early 1960s, and pieces of construction material such as fired clay and wooden support poles have been found. Artifacts typical of a hunting-fishing community such as harpoons and fish hooks were discovered here. Clay figuines shaped like lizards and bovids were also discovered.[1][7] There is also evidence of animal husbandry being practiced.

- Tamale Stone rasps were found.[8]

- Tolundipe

Central woodland savanna

Nearly all of the archaeological sites that have been detected or excavated in this region are found near the modern day city of Kumasi.

- Amuowi

- Banda

- Bonoase Outlines of huts and stone foundations have been excavated.

- Boyase Hill At this hill, which has a radius of approximately 250 meters, polished stone axes, stone arm rings and projectile points were found. Most curiously, a clay dog figurine was discovered.[7]

- Fiakwase

- Kintampo First excavated in 1966, evidence of animal husbandry is found here, as well as remnants of sheep, cattle, goats, and larger mammals such as elephants and hippopotamus.[7][9]

- Jema

- Mumute Outlines of dwellings and stone foundations have been excavated.

- Nyamogo

- Pumpuano

- Wenchi

Southern forest

- Boyasi Outlines of dwellings and stone foundations have been excavated. Large stones of granite with major signs of wear were found at the edge of the village that were used to polish stone stone tools and decorations.

- Buoho

- Buruburo

- Christian Village Located near the Atlantic coast near modern-day Accra, clay cylinders have been found at the site which are remnants of ancient dwellings.

- Mampongtin

- Nkobin

- Nkukoa Buoho This site, located near Boyasi, seems to be a treasure trove of artifacts and features for researchers. Rasps, pottery and stone tools were found in large numbers.

- Somanya

- Wiwi

Inhabitants

The people of Kintampo lived in open-air villages composed of rectangular structures made from wattle and daub construction techniques. Some house used mud, some used clays, and many were found to have been supported by wooden poles and some had foundations of stones like granite and laterite. Rock shelters were also used as dwellings, especially to the south, near the Atlantic coast. A society can not live without a water supply, and at Kintampo there is no exception. Many settlements were situated along the White Volta river which runs all the way through Ghana, from north to south, eventually dumping into the Atlantic. Other settlements, such as the rock shelters of southwestern Ghana and southeastern Côte d'Ivoire were along near the Atlantic coast.[10] They also kept domesticated dogs and goats and cattle.

Food

The Kintampo site is most often studied by archaeologists who are interested in seeing how people made the change between foraging and horticulture and agriculture as a way of producing food. Kintampo is seen as an example of neither foraging or farming, but somewhere in between. As practitioners of sedentism, derived from the word sedentary, the people of Kintampo spent more time in their villages and less time wandering around, hunting and gathering food. They took advantage of plants that were native to the area, and although technically they were not farming, they did influence the evolution of plants, effectively being some of the first to domesticate plants in Africa.

Pearl millet is a crop that is well suited to hot climates, and is thought to have been first domesticated in the area. It is speculated that the people of Kintampo may have deliberately adapted it to mature faster, to allow for quicker harvest. Its charred remains have been excavated at Kintampo and was valuable to people living in west Africa because it could be stored after harvest to be used at a later date. There is evidence of trade of foods with other people throughout the region; one item of evidence is that the millet has been found with shell beads that would have been imported from the ocean.[11]

Another important staple to the people who settled at Kintampo was the oil palm. The oil palm was used at Kintampo starting at least 4000 years ago. A very useful plant in many ways, it serves as a source of drink, food, and construction material. It was allowed to flourish in the region due to its preference for a constant warm climate and high rainfall. As a food, the oil can be extracted from the mesocarp which covers the plant, and the kernal which is also edible by itself. It is an excellent source of vitamin A, which would have helped to support a growing population. It is speculated that ceramic techniques were improved so that the nut of the oil palm could be further cooked.

The cowpea, incense tree, hackberry, yams, and sorghum, are also known to have been grown. Grasses were most likely not harvested as often, as the climate makes it difficult for grasses to grow. Kintampo people also kept livestock; goats, sheep, and cattle remains have been found. Other wild animals such as monitor lizards, snails, guineafowl, vervet monkey, baboon, turtles and tortoises royal and duiker antelopes, giant pouched and cane rats were hunted as game.[12]

Artifacts

.jpg)

Numerous types of tools have been excavated at Kintampo, including polished axes crafted from calc-chlorite schist, many types and sizes of grinding stones, small, quartz microlith projectile points of various shapes and styles, and stone celts. A few harpoons have been found, but these are rare.

The knapping technique they used is well understood by lithics experts. The stone core was placed on a hard level surface such as a large rock, log, or trunk, then struck from above, forcing flakes to separate from the material from underneath. This use of a makeshift anvil is typical of bipolar percussion.[13]

There is some confusion about the purpose of a number of small stone and ceramic objects that are cigar-shaped and rasp-like. They are thought to be tools for creating pottery, of which bowls and jars seem to be the most common. The jars ranged from 12–44 cm in diameter. The bowls were slightly smaller on average, ranging from 10–30 cm. Many times these pots were decorated with a comb-like or rake pattern. These were likely used not only for the storage of food and water, but also for boiling and crafting sauces.[14] The pottery appears to have been fired in a pit, typical of early ceramic practices.[11] In fact, the pottery of Kintampo have been widely studied, in fact it is possibly the most studied later stone age ceramics in West Africa.[11] Pieces of a substance known as daga has been found along with the stone artifacts. Daga is chunks of ceramics that have been visibly marked by sticks or other pole-like implements. Somewhat common at Kintampo sites, these are understood to represent occupation in dwellings.[13]

The Kintampo culture is known for possibly the first occurrences of figurative art and objects of personal decoration in West Africa.[8] Stone arm bands that would have been worn as decoration have been found at several Kintampo sites. At the sites of Boyase hill and Ntersero, clay figurines of animals like dogs, lizards and cows were found, though it is not well understood what their meaning might be. This is all very important to those who study the humanities, as the emergence of art and the depiction of life through art is of great interest to both art historians and archaeologists alike.[7]

Legacy

The rockshelters of Kintampo appear to be abandoned by the second century BCE, and then in the early first millennium CE, iron metallurgy became the dominant technology of the region.[14]

The area became home to the Akan, who later built the Ashanti Empire in the 18th century. It was a large kingdom that used firearms traded to them by Europeans to effectively conquer neighboring territories. The Ashanti enslaved their enemies and prisoners of war and made a profit by selling them in the transatlantic slave trade.[15]

See also

Sources

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Anquandah, James (1995) The Kintampo Complex: a case study of early sedentism and food production in sub-Sahelian west Africa, pp. 255–259 in Shaw, Thurstan, Andah, Bassey W and Sinclair, Paul (1995). The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11585-X

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 McBrearty, Sally; Brooks, Allison (2000). "The revolution that wasn't: A new interpretation of the origin of modern human behaviour". Journal of Human Evolution 39: 453–563. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0435.

- ↑ Sahara's Abrupt Desertification Started by Changes in Earth's Orbit

- ↑ Christopher Ehret (2002)The Civilizations of Africa. University Press of Virginia. ISBN 081392085X.

- ↑ Watson, Derek J. (2005). "Under the rocks: reconsidering the origin of the Kintampo Tradition and the development of food production in the Savanna-Forest/Forest of West Africa". Journal of African Archaeology 3 (1): 3–55. doi:10.3213/1612-1651-10035.

- ↑ Stahl, Ann Brower (1986). "Early Food Production in West Africa: Rethinking the Role of the Kintampo Culture". Current Anthropology 27 (5): 532–536. doi:10.1086/203486. JSTOR 2742871.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "Archaeological Sites and other sites of historical-cultural relevance to Ghana". Ghana Museums and Monuments Board.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Watson, Derek J. (August 17, 2010). "Within savanna and forest: A review of the Late Stone Age Kintampo Tradition, Ghana". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 45 (2): 141–172. doi:10.1080/0067270X.2010.491361. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ↑ De Corse, Christopher; Berry, Sarah; Spiers, Sam (2001). "TRADITION SUMMARY: WEST AFRICAN IRON AGE". Encyclopedia of Prehistory:Africa 1: 313–318. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-1193-9_26.

- ↑ Quickert, Nicole A.; Godfrey-Smith, Dorothy I.; Casey, Joanna L. (2003). "Optical and thermoluminescence datingof Middle Stone Age and Kintampo bearingsediments at Birimi, a multi-component archaeological site in Ghana" (PDF). Quaternary Science 22. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(03)00050-7. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 D'Andrea, Catherine (2002-09-01). "Pearl Millet and Kintampo Subsistence" (PDF). African ArchaeologicalReview 19 (3). doi:10.1023/A:1016518919072.

- ↑ Logan, Amanda L.; D'Andrea, A. Catherine (6 February 2012). "Oil palm, arboriculture, and changing subsistence practices during Kintampo times (3600 e 3200 BP, Ghana)" (PDF). Quaternary International 249. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2010.12.004.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Kent, Susan (1998). Gender in African Prehistory. Walnut Creek, CA: AltMira Press. pp. 89–98. ISBN 978-0-7619-8968-4.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Stahl, Ann Brower (1995) Intensification in the west African Late Stone Age: a view from central Ghana, pp. 261–269 in Shaw, Thurstan, Andah, Bassey W and Sinclair, Paul (1995). The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11585-X

- ↑ Collins, Robert O. and Burns, James M. (2007). A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 138-141, ISBN 978-0-521-68708-9