King Kong

| King Kong | |

|---|---|

| King Kong character | |

The original stop-motion animated King Kong in the 1933 film fighting an airplane Boeing P-12 on top of the Empire State Building. | |

| First appearance | King Kong (1933 film) |

| Last appearance | King Kong (2005 film) |

| Created by |

Edgar Wallace Merian C. Cooper |

| Portrayed by |

Willis O'Brien (1933) (animator) Rick Baker (1976) Peter Elliot (1986) Andy Serkis (2005) |

| Information | |

| Species | Giant Gorilla |

King Kong is a giant movie monster, resembling a colossal gorilla, that has appeared in various media since 1933. The character first appeared in the 1933 film King Kong, which received universal acclaim upon its initial release and re-releases. The film was remade in 1976 and once again in 2005. The character has become one of the world's most famous movie icons, having inspired countless sequels, remakes, spin-offs, imitators, parodies, cartoons, books, comics, video games, theme park rides, and even a stage play.[1] His role in the different narratives varies, ranging from a rampaging monster to a tragic antihero.

Overview

The King Kong character was conceived and created by U.S. filmmaker Merian C. Cooper. In the original film, the character's name is Kong, a name given to him by the inhabitants of "Skull Island" in the Pacific Ocean, where Kong lives along with other over-sized animals such as a plesiosaur, pterosaurs, and dinosaurs. An American film crew, led by Carl Denham, captures Kong and takes him to New York City to be exhibited as the "Eighth Wonder of the World".

Kong escapes and climbs the Empire State Building (the original World Trade Center in the 1976 remake), only to fall from the skyscraper as Denham comments, "It was beauty that killed the beast," for he climbs the building in the first place only in an attempt to protect Ann Darrow, an actress originally offered up to Kong as a sacrifice (in the 1976 remake, the character is named Dwan).

A mockumentary about Skull Island that appears on the DVD for the 2005 remake (but originally seen on the Sci-Fi Channel at the time of its theatrical release) gives Kong's scientific name as Megaprimatus kong and states that his species may be related to Gigantopithecus.

Filmography

- King Kong (1933) – The original film is remembered for its pioneering special effects using stop motion models, and evocative story.

- The Son of Kong (1933) – A sequel released the same year, it concerns a return expedition to Skull Island that discovers Kong's son. The critics' response to the film was generally mixed, but it was successful.

- King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) – A film produced by Toho Studios in Japan, it brought the titular characters to life via detailed rubber and fur costumes, and presented both characters for the first time in color. The Toho version of Kong is much larger than the one in the original film.

- King Kong Escapes (1967) – Another Toho film (co-produced with Rankin/Bass) in which King Kong faces both a mechanical double, dubbed Mechani-Kong, and a giant theropod dinosaur known as Gorosaurus (who would appear in Toho's Destroy All Monsters the next year). This movie was loosely based on the contemporaneous cartoon television program, as indicated by the use of its recurring villain, Dr. Who/Dr. Huu, in the same capacity, Mechani-Kong as an enemy, Mondo Island as Kong's home and a female character named Susan.

- King Kong (1976) – A contemporary remake by film producer Dino De Laurentiis, released by Paramount Pictures, and directed by John Guillermin. Jessica Lange, Jeff Bridges and Charles Grodin starred. The film received mixed reviews, but it was a commercial success, and its reputation has improved over the last few years. It was co-winner of an Oscar for special effects (shared with Logan's Run).

- King Kong Lives (1986) – Released by De Laurentiis Entertainment Group (DEG). Starring Linda Hamilton, a sequel by the same producer and director as the 1976 film which involves Kong surviving his fall from the sky and requiring a coronary operation. It includes a female member of Kong's species, who, after supplying a blood transfusion that enables the life-saving surgery, escapes and mates with Kong, becoming pregnant with his offspring. Trashed by critics, this was a box-office failure.

- King Kong (2005) – A Universal Pictures remake of the original (set in the original film's 1933 contemporary setting) by Academy award-winning New Zealand director Peter Jackson, best known for directing the Lord of the Rings film trilogy. The most recent incarnation of Kong is also the longest, running three hours and eight minutes. Winner of three Academy Awards for visual effects, sound mixing, and sound editing. It received mainly positive reviews and a box office success, grossing over $550 million worldwide.

- Kong: Skull Island (2017) – A Universal Pictures/Legendary Pictures co-production prequel set to be released on March 10, 2017 and to feature a "new, distinct timeline".[2] The studio announced that Tom Hiddleston will star as the lead along with J. K. Simmons.[3] Michael Keaton is currently in talks to join the production.[4] The film will be directed by Jordan Vogt-Roberts with the screenplay to be written by Max Borenstein[5] and John Gatins.[6] Simmons told MTV that the film will take place in Detroit in 1971.[7]

Theatre

In mid-2012, it was announced that a musical adaptation of the story (endorsed by Merian C. Cooper's estate) was going to be staged in Melbourne at the Regent Theatre. The show premiered on June 15, 2013, with music by Marius De Vries. The huge King Kong puppet was created by Global Creature Technology.[8]

Print media

The literary tradition of a remote and isolated jungle populated by natives and prehistoric animals was rooted in the "Lost World" genre, specifically Arthur Conan Doyle's 1912 novel The Lost World, which was itself made into a silent film of that title in 1925 that Doyle lived long enough to see. The special effects of that film were created by Willis O'Brien, who went on to do those for the 1933 King Kong. Another important book in that literary genre is Edgar Rice Burroughs' 1918 novel The Land That Time Forgot.

A novelization of the original King Kong film was published in December 1932 as part of the film's advance marketing. The novel was credited to Edgar Wallace and Merian C. Cooper, although it was in fact written by Delos W. Lovelace. Apparently, however, Cooper was the key creative influence, saying that he got the initial idea after he had a dream that a giant gorilla was terrorizing New York City. In an interview, author-artist Joe DeVito explains:

- "From what I know, Edgar Wallace, a famous writer of the time, died very early in the process. Little if anything of his ever appeared in the final story, but his name was retained for its saleability ... King Kong was Cooper's creation, a fantasy manifestation of his real life adventures. As many have mentioned before, Cooper was Carl Denham. His actual exploits rival anything Indiana Jones ever did in the movies."[9]

This conclusion about Wallace's contribution agrees with The Making of King Kong, by Orville Goldner and George E. Turner (1975). Wallace died of pneumonia complicated by diabetes on February 10, 1932, and Cooper later said, "Actually, Edgar Wallace didn't write any of Kong, not one bloody word...I'd promised him credit and so I gave it to him" (p. 59). However, in the October 28, 1933, issue of Cinema Weekly, the short story "King Kong" by Edgar Wallace and Draycott Montagu Dell (1888–1940) was published. The short story appears in Peter Haining's Movie Monsters (1988) published by Severn House in the UK. Dell was a journalist and wrote books for children, such as the 1934 story and puzzle book Stand and Deliver. He was a co-worker and close friend of Edgar Wallace.

The original publisher was Grosset & Dunlap. Paperback editions by Bantam (U.S.) and Corgi (U.K.) came out in the 1960s, and it has since been republished by Penguin and Random House.

In 1933, Mystery magazine published a King Kong serial under the byline of Edgar Wallace. This is unrelated to the 1932 novel. The story was serialized into two parts that were published in the February 1933 and March 1933 issues of the magazine. As well, that October, King Kong was serialized in the pulp magazine Boys Magazine (Vol 23. No. 608).[10]

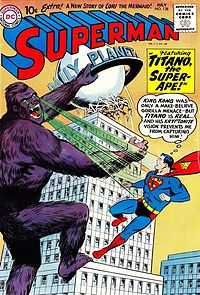

Over the decades, there have been numerous comic book adaptations of the 1933 King Kong by various comic-book publishers, and one of the 2005 remake by Dark Horse Comics.

Kong: King of Skull Island, an illustrated novel labeled as an authorized sequel to the 1932 novelization of King Kong was published in 2004 by DH Press, a subsidiary of Dark Horse Comics. A large-paperback edition was released in 2005. Authorized by the family and estate of Merian C. Cooper, the book was created and illustrated by Joe DeVito, written by Brad Strickland with John Michlig, and includes an introduction by Ray Harryhausen. The novel's story ignores the existence of Son of Kong (1933) and continues the story of Skull Island with Carl Denham and Jack Driscoll in the late 1950s, through the novel's central character, Vincent Denham. (Ann Darrow does not appear, but is mentioned several times.) The novel also becomes a prequel that reveals the story of the early history of Kong, of Skull Island, and of the natives of the island. The book's official website claims a motion picture version is in development.[11]

Merian C. Cooper’s King Kong was written by Joe DeVito and Brad Strickland for the Merian C. Cooper Estate, and published by St. Martin's Press, 2005. It is a full rewrite of the original 1932 novelization, which updates the language, paleontology and adds five new chapters. Some additional elements and characters tie into Kong: King of Skull Island enabling the two separate books to form a continuous storyline.

The novelization of the 2005 movie was written by Christopher Golden, based on the screenplay by Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, and Peter Jackson, which was, of course, in turn based on the original story by Merian C. Cooper & Edgar Wallace. (The Island of the Skull, a "prequel" novel to the 2005 movie, was released at nearly the same time.) In November 2005, to coincide with the release of the 2005 movie, Weta Workshop released a collection of concept art from the film entitled The World of Kong: A Natural History of Skull Island. While similar collections of production art have been released in the past to complement other movies, The World of Kong is unusual — if not unique — in that it is written and designed to resemble and read like an actual nature guide and historical record, not a movie book.

Also in 2005, Ibooks, Inc published Kong Reborn by Russell Blackford. Ignoring all films except the 1933 original, it is set in the present day. Carl Denham's grandson finds some genetic material from the original Kong and attempts to clone him. Late in 2005, the BBC and Hollywood trade papers reported that a 3-D stereoscopic version of the 2005 film was being created from the animation files, and live actors digitally enhanced for 3-D display. This may be just an elaborate 3-D short for Universal Studios Theme Park, or a digital 3-D version for general release in the future.

To coincide with the 80th anniversary of both characters, Altus Press announced on January 29, 2013, that King Kong would meet pulp hero Doc Savage in a new, officially sanctioned book written by Will Murray and based on concepts by artist Joe DeVito, who will also do the cover artwork. Set in 1920, shortly after returning from military service during World War One, Doc Savage searches for his long-lost grandfather, the legendary mariner Stormalong Savage, with his father, the explorer Clark Savage, Sr., that ultimately leads father and son to the mysterious Skull Island and its prehistoric denizens, including King Kong. Doc Savage: Skull Island was released in March 2013.[12]

Appearances and abilities

In his first appearance in King Kong (1933), Kong was a gigantic prehistoric ape, or as RKO's publicity materials described him, "A prehistoric type of ape."[13] While gorilla-like in appearance, he had a vaguely humanoid look and at times walked upright in an anthropomorphic manner. Indeed, Carl Denham describes him as being "neither beast nor man". Like most simians, Kong possesses semi-human intelligence and great physical strength. Kong's size changes drastically throughout the course of the film. While creator Merian C. Cooper envisioned Kong as being "40 to 50 feet tall",[14] animator Willis O'Brien and his crew built the models and sets scaling Kong to be only 18 feet tall on Skull Island, and rescaled to be 24 feet tall in New York.[15] This did not stop Cooper from playing around with Kong's size as he directed the special effect sequences; by manipulating the sizes of the miniatures and the camera angles, he made Kong appear a lot larger than O'Brien wanted, even as large as 60 feet in some scenes. As Cooper stated in an interview, I was a great believer in constantly changing Kong's height to fit the settings and the illusions. He's different in almost every shot; sometimes he's only 18 feet tall and sometimes 60 feet or larger. This broke every rule that O'Bie and his animators had ever worked with, but I felt confident that if the scenes moved with excitement and beauty, the audience would accept any height that fitted into the scene. For example if Kong had only been 18 feet high on the top of the Empire State Building, he would have been lost, like a little bug; I constantly juggled the heights of trees and dozens of other things. The one essential thing was to make the audience enthralled with the character of Kong so that they wouldn't notice or care that he was eighteen feet high or forty, just as long as he fitted the mystery and excitement of the scenes and action.[16] Concurrently, the Kong bust made for the film was built in scale with a 40-foot ape,[17] while the full sized hand of Kong was built in scale with a 70-foot ape.[18] Meanwhile, RKO's promotional materials listed Kong's official height as 50 feet.[13]

In 1975, Producer Dino De Laurentiis paid RKO for the remake rights to King Kong. This resulted in King Kong (1976). This Kong was an upright walking anthropomorphic ape, appearing even more human-like than the original. Also like the original, this Kong had semi-human intelligence and vast strength. In the 1976 film, Kong was scaled to be 42 feet tall on Skull island and rescaled to be 55 feet tall in New York.[19] 10 years later, DDL received permission from Universal to do a sequel, King Kong Lives. Kong more or less had the same appearance and abilities, only he tended to walk on his knuckles more often and was enlarged, being scaled to be 60 feet.[20]

Universal Studios had planned to do a King Kong remake as far back as 1976. They finally followed through almost 30 years later, with a three-hour film directed by Peter Jackson. Jackson opted to make Kong a gigantic silverback gorilla without any anthropomorphic features. Kong looked and behaved more like a real gorilla: he had a large herbivore's belly, walked on his knuckles without any upright posture, and even beat his chest with his palms as opposed to clenched fists. In order to ground his Kong in realism, Jackson and the Weta Digital crew gave a name to his fictitious species, Megaprimatus kong, which was said to have evolved from the Gigantopithecus. Kong was the last of his kind. He was portrayed in the film as being quite old with graying fur, and battle-worn with scars, wounds, and a crooked jaw from his many fights against rival creatures. He is the most dominant being on the island; the king of his world. Like his predecessors, he possesses considerable intelligence and great physical strength; he also appears far more nimble and agile. This Kong was scaled to be only 25 feet tall on both Skull Island and in New York.[21]

Jackson describes his central character: “We assumed that Kong is the last surviving member of his species. He had a mother and a father and maybe brothers and sisters, but they’re dead. He’s the last of the huge gorillas that live on Skull Island, and the last one when he goes...there will be no more. He’s a very lonely creature, absolutely solitary. It must be one of the loneliest existences you could ever possibly imagine. Every day, he has to battle for his survival against very formidable dinosaurs on the island, and it’s not easy for him. He’s carrying the scars of many former encounters with dinosaurs. I’m imagining he’s probably 100 to 120 years old by the time our story begins. And he has never felt a single bit of empathy for another living creature in his long life; it has been a brutal life that he’s lived.”[22]

Origin of the name

Merian C. Cooper was very fond of strong hard sounding words that started with the letter "K". Some of his favorite words were Komodo, Kodiak and Kodak.[23] When Cooper was envisioning his giant terror gorilla idea, he wanted to capture a real gorilla from the Congo and have it fight a real Komodo Dragon on Komodo Island. (This scenario would eventually evolve into Kong's battle with the Tyrannosaur on Skull Island when the film was produced a few years later at RKO). Cooper's friend Douglas Burden's trip to the island of Komodo and his encounter with the Komodo Dragons there was a big influence on the Kong story.[24] Cooper was fascinated by Burdens adventures as chronicled in his book Dragon Lizards of Komodo where he referred to the animal as the "King of Komodo".[23] It was this phrase along with Komodo and C(K)ongo (and his overall love for hard sounding K words)[25] that gave him the idea to name the giant ape Kong. He loved the name as it had a "mystery sound" to it.

When Cooper got to RKO and wrote the first draft of the story, it was simply referred to as The Beast. RKO executives were unimpressed with the bland title. David O. Selznick suggested Jungle Beast as the film's new title,[26] but Cooper was unimpressed and wanted to name the film after the main character. He stated he liked the "mystery word" aspect of Kong's name and that the film should carry "the name of the leading mysterious, romantic, savage creature of the story" such as with Dracula and Frankenstein.[26] RKO sent a memo to Cooper suggesting the titles Kong: King of Beasts, Kong: The Jungle King, and Kong: The Jungle Beast, which combined his and Selznick's proposed titles.[26] As time went on, Cooper would eventually name the story simply Kong while Ruth Rose was writing the final version of the screenplay. Because David O. Selznick thought that audiences would think that the film, with the one word title of Kong, would be mistaken as a docudrama like Grass and Chang, which were one-word titled films that Cooper had earlier produced, he added the "King" to Kong's name to differentiate.[27]

Legal rights

While one of the most famous movie icons in history, King Kong's intellectual property status has been questioned since his creation, featuring in numerous allegations and court battles. The rights to the character have always been split up with no single exclusive rights holder. Different parties have also contested that various aspects are public domain material and therefore ineligible for trademark or copyright status.

When Merian C. Cooper created King Kong, he assumed that he owned the character, which he had conceived in 1929, outright. Cooper maintained that he had only licensed the character to RKO for the initial film and sequel but had otherwise owned his own creation. In 1935, Cooper began to feel something was amiss when he was trying to get a Tarzan vs. King Kong project off the ground for Pioneer Pictures (where he had assumed management of the company). After David O. Selznick suggested the project to Cooper, the flurry of legal activity over using the Kong character that followed—Pioneer having become a completely independent company by this time and access to properties that RKO felt were theirs was no longer automatic—gave Cooper pause as he came to realize that he might not have full control over the figment of his own imagination.[28]

Years later in 1962, Cooper had found out that RKO was licensing the character through John Beck to Toho studios in Japan for a film project called King Kong vs. Godzilla. Cooper had assumed his rights were unassailable and was bitterly opposed to the project. In 1963 he filed a lawsuit to enjoin distribution of the movie against John Beck as well as Toho and Universal (the film's U.S. copyright holder).[29] Cooper discovered that RKO had also profited from licensed products featuring the King Kong character such as model kits produced by Aurora Plastics Corporation. Cooper's executive assistant, Charles B FitzSimons, stated that these companies should be negotiating through him and Cooper for such licensed products and not RKO. In a letter Cooper wrote to Robert Bendick he stated,

My hassle is about King Kong. I created the character long before I came to RKO and have always believed I retained subsequent picture rights and other rights. I sold to RKO the right to make the one original picture King Kong and also, later, Son of Kong, but that was all.[30]

Cooper and his legal team offered up various documents to bolster the case that Cooper had owned King Kong and only licensed the character to RKO for two films, rather than selling him outright. Many people vouched for Cooper's claims including David O. Selznick (who had written a letter to Mr. A. Loewenthal of the Famous Artists Syndicate in Chicago in 1932 stating (in regards to Kong), "The rights of this are owned by Mr. Merian C. Cooper."[30] But Cooper had lost key documents through the years (he discovered these papers missing after he returned from his World War II military service) such as a key informal yet binding letter from Mr. Ayelsworth (then president of the RKO Studio Corp) and a formal binding letter from Mr. B. B. Kahane (the current president of RKO Studio Corp) confirming that Cooper had only licensed the rights to the character for the two RKO pictures and nothing more.[31]

Unfortunately without these letters it seemed Cooper's rights were relegated to the Lovelace novelization that he had copyrighted (he was able to make a deal for a Bantam Books paperback reprint and a Gold Key comic adaptation of the novel, but that was all he could do). Cooper's lawyer had received a letter from John Beck's lawyer, Gordon E Youngman, that stated:

For the sake of the record, I wish to state that I am not in negotiation with you or Mr. Cooper or anyone else to define Mr. Cooper's rights in respect of King Kong. His rights are well defined, and they are non-existent, except for certain limited publication rights.[32]

In a letter addressed to Douglas Burden, Cooper lamented:

It seems my hassle over King Kong is destined to be a protracted one. They'd make me sorry I ever invented the beast, if I weren't so fond of him! Makes me feel like Macbeth: "Bloody instructions which being taught return to plague the inventor."[32]

The rights over the character did not flare up again until 1975, when Universal Studios and Dino De Laurentiis were fighting over who would be able to do a King Kong remake for release the following year. De Laurentiis came up with $200,000 to buy the remake rights from RKO.[33] When Universal got wind of this, they filed a lawsuit against RKO claiming that they had a verbal agreement from them in regards to the remake. During the legal battles that followed, which eventually included RKO countersuing Universal, as well as De Laurentiis filing a lawsuit claiming interference, Colonel Richard Cooper (Merian's son and now head of the Cooper estate) jumped into the fray.[34]

During the battles, Universal discovered that the copyright of the Lovelace novelization had expired without renewal, thus making the King Kong story a public domain one. Universal argued that they should be able to make a movie based on the novel without infringing on anyone's copyright because the characters in the story were in the public domain within the context of the public domain story.[35] Richard Cooper then filed a cross-claim against RKO claiming while the publishing rights to the novel had not been renewed, his estate still had control over the plot/story of King Kong.[34]

In a four-day bench trial in Los Angeles, Judge Manuel Real made the final decision and gave his verdict on November 24, 1976, affirming that the King Kong novelization and serialization were indeed in the public domain, and Universal could make its movie as long as it did not infringe on original elements in the 1933 RKO film,[36] which had not passed into public domain.[37] (Universal postponed their plans to film a King Kong movie, called The Legend of King Kong, for at least 18 months, after cutting a deal with Dino De Laurentiis that included a percentage of box office profits from his remake.)[38]

However, on December 6, 1976, Judge Real made a subsequent ruling, which held that all the rights in the name, character, and story of King Kong (outside of the original film and its sequel) belonged to Merian C. Cooper's estate. This ruling, which became known as the "Cooper Judgment," expressly stated that it would not change the previous ruling that publishing rights of the novel and serialization were in the public domain. It was a huge victory that affirmed the position Merian C. Cooper had maintained for years.[36] Shortly thereafter, Richard Cooper sold all his rights (excluding worldwide book and periodical publishing rights) to Universal in December 1976. In 1980 Judge Real dismissed the claims that were brought forth by RKO and Universal four years earlier and reinstated the Cooper judgement.[39]

In 1982 Universal filed a lawsuit against Nintendo, which had created an impish ape character called Donkey Kong in 1981 and was reaping huge profits over the video game machines. Universal claimed that Nintendo was infringing on its copyright because Donkey Kong was a blatant rip-off of King Kong.[39] During the court battle and subsequent appeal, the courts ruled that Universal did not have exclusive trademark rights to the King Kong character. The courts ruled that trademark was not among the rights Cooper had sold to Universal, indicating that "Cooper plainly did not obtain any trademark rights in his judgment against RKO, since the California district court specifically found that King Kong had no secondary meaning."[37] While they had a majority of the rights, they did not outright own the King Kong name and character.[40] The courts ruling noted that the name, title, and character of Kong no longer signified a single source of origin. The courts also pointed out that Kong rights were held by three parties:

- RKO owned the rights to the original film and its sequel.

- The Dino De Laurentiis company (DDL) owned the rights to the 1976 remake.

- Richard Cooper owned worldwide book and periodical publishing rights.[40]

The judge then ruled that "Universal thus owns only those rights in the King Kong name and character that RKO, Cooper, or DDL do not own."[41]

The court of appeals would also note:

First, Universal knew that it did not have trademark rights to King Kong, yet it proceeded to broadly assert such rights anyway. This amounted to a wanton and reckless disregard of Nintendo's rights.Second, Universal did not stop after it asserted its rights to Nintendo. It embarked on a deliberate, systematic campaign to coerce all of Nintendo's third party licensees to either stop marketing Donkey Kong products or pay Universal royalties.

Finally, Universal's conduct amounted to an abuse of judicial process, and in that sense caused a longer harm to the public as a whole. Depending on the commercial results, Universal alternatively argued to the courts, first, that King Kong was a part of the public domain, and then second, that King Kong was not part of the public domain, and that Universal possessed exclusive trademark rights in it. Universal's assertions in court were based not on any good faith belief in their truth, but on the mistaken belief that it could use the courts to turn a profit.[42]

Because Universal misrepresented their degree of ownership of King Kong (claiming they had exclusive trademark rights when they knew they didn't) and tried to have it both ways in court regarding the "public domain" claims, the courts ruled that Universal acted in bad faith (see Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.). They were ordered to pay fines and all of Nintendo's legal costs from the lawsuit. That, along with the fact that the courts ruled that there was simply no likelihood of people confusing Donkey Kong with King Kong,[40] caused Universal to lose the case and the subsequent appeal.

Since the court case, Universal still retains the majority of the character rights. In 1986 they opened a King Kong ride called King Kong Encounter at their Universal Studios Tour theme park in Hollywood (which was destroyed in 2008 by a backlot fire), and followed it up with the Kongfrontation ride at their Orlando park in 1990 (which was closed down in 2002 due to maintenance issues). They also finally made a King Kong film of their own, King Kong (2005). In the summer of 2010, Universal opened a new 3D King Kong ride called King Kong: 360 3-D at their Hollywood park replacing the destroyed King Kong Encounter.[43] A King Kong-themed dueling roller coaster is part of the proposed Universal Studios Dubailand in the United Arab Emirates.

The Cooper estate retains publishing rights for the content they claim. In 1990 they licensed a six-issue comic book adaptation of the story to Monster Comics, and commissioned an illustrated novel in 1994 called Anthony Browne's King Kong. In 2004 and 2005, they commissioned a new novelization to be written by Joe Devito called Merian C. Cooper's King Kong to replace the original Lovelace novelization (the original novelization's publishing rights are still in the public domain) and Kong: King of Skull Island, a prequel/sequel novel that ties into the original story. In 2013, Richard M. Cooper (who's thanked in the books credits) endorsed Doc Savage: Skull Island, a crossover book featuring King Kong and Doc Savage that was written by Will Murray and based on concepts by Joe DeVito. They are also involved in a musical stage play based on the story, called King Kong The Eighth Wonder of the World which premiered in June 2013.[44][45] The production also involved Global Creatures, the company behind the Walking with Dinosaurs arena show.[46]

RKO (whose rights consisted of only the original film and its sequel) had its film library acquired by Ted Turner in 1986 via his company Turner Entertainment. Turner merged his company into Time Warner in 1995, which is how they own the rights to those two films today.

DDL (whose rights were limited to only their 1976 remake) did a sequel in 1986 called King Kong Lives (but they still needed Universal's permission to do so).[47] Today most of DDL's film library is owned by Studio Canal, which includes the rights to those two films. The domestic (North American) rights to King Kong though, still remain with the film's original distributor Paramount Pictures, with Trifecta Entertainment & Media handling television rights to the film via their licence with Paramount.

King Kong (Toho)

| Godzilla film series character | |

|---|---|

| King Kong | |

| |

| Relations | Mechani-Kong (robot replica) |

| First appearance | King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) |

| Last appearance | King Kong Escapes (1967) |

| Created by | Merian C. Cooper |

| Portrayed by | Shoichi Hirose (1962) Haruo Nakajima (1967) |

Overview

In the 1960s, Japanese studio Toho licensed the character from RKO and produced two films that featured the character, King Kong vs Godzilla (1962) and King Kong Escapes (1967). Toho's interpretation differed greatly from the original in size and abilities.

Among kaiju, King Kong was suggested to be among the most powerful in terms of raw physical force, possessing strength and durability that rivaled that of Godzilla. As one of the few mammal-based kaiju, Kong's most distinctive feature was his intelligence. He demonstrated the ability to learn and adapt to an opponent's fighting style, identify and exploit weaknesses in an enemy, and utilize his environment to stage ambushes and traps.[48]

In King Kong vs. Godzilla, Kong was scaled to be 45 meters (147 feet) tall. This version of Kong was given the ability to harvest electricity as a weapon.[49] In King Kong Escapes, Kong was scaled to be 20 meters (65 feet) tall. This version was more similar to the original, where he relied on strength and intelligence to fight and survive.[50] Rather than residing on Skull Island, Toho's version resided on Faro Island in King Kong vs. Godzilla and on Mondo Island in King Kong Escapes.

In 1966, Toho planned to produce "Operation Robinson Crusoe: King Kong vs. Ebirah" as a co-production with Rankin/Bass Productions however, Ishirō Honda was unavailable at the time to direct the film and Rankin/Bass backed out of the project, along with the King Kong license.[51] Toho still proceeded with the production, replacing King Kong with Godzilla at the last minute and shot the film as Godzilla, Ebirah, Mothra: Big Duel in the South Seas. Elements of King Kong's character remained in the film, reflected on Godzilla's uncharacteristic behavior and attraction to the female character Dayo.[52] Toho and Rankin/Bass later negotiated their differences and co-produced King Kong Escapes in 1967, loosely based on Rankin/Bass' animated show.

Toho Studios wanted to remake King Kong vs. Godzilla, which was the most successful of the entire Godzilla series of films, in 1991 to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the film as well as to celebrate Godzilla's upcoming fortieth anniversary. However they were unable to obtain the rights to use Kong, and inititially intended to use Mechani-Kong as Godzilla's next adversary. However it was soon learned that even using a mechanical creature who resembled Kong would be just as problematic legally and financially for them. As a result, the film became Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah, with no further attempts to use Kong in any way.

Appearances

- Films

- King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962)

- King Kong Escapes (1967)

Other appearances

Television

- The King Kong Show (1966). In this cartoon series, the giant gorilla befriends the Bond family, with whom he goes on various adventures, fighting monsters, robots, mad scientists and other threats. Produced by Rankin/Bass, the animation was provided in Japan by Toei Animation, making this the very first anime series to be commissioned right out of Japan by an American company. The show debuted with an hour-long episode and then was followed by 24 half hour episodes that aired on ABC. This was also the cartoon that resulted in the production of Toho's Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster (originally planned as a Kong film) and King Kong Escapes.

- Kong: The Animated Series (2000). An animated production from BKN International set many decades after the events of the original film. "Kong" is cloned by a female scientist named Dr. Lorna Jenkins who also used the DNA of her grandson Jason to bring it to life. Jason uses the Cyber-Link to combine with Kong in order to fight evil. This show, coming a few years after the release of Centropolis' Godzilla: The Series repeated at least two of the monsters (although with vastly different backgrounds) seen in the Godzilla series. The show ran 40 episodes and aired on Fox Kids. After the series ended, two direct-to-DVD movies were produced. Kong: King of Atlantis, released in 2005 and Kong: Return to the Jungle, released in 2007. The first movie was produced to try and cash in on the 2005 King Kong remake and that same year, Toon Disney's "Jetix" would air not only this movie but the original series as well to also take advantage of the 2005 movie's release.

- Kong - King Of The Apes (2016). An animated series by 41 Entertainment and to air on Netflix. The first episode will air as a two-hour movie followed by 12 half-hour episodes. Avi Arad will be the executive producer of the series. The series Synopsis reads "Set in 2050, Kong becomes a wanted fugitive after wrecking havoc at Alcatraz Island’s Natural History and Marine Preserve. What most humans on the hunt for the formidable animal don’t realize, though, is that Kong was framed by an evil genius who plans to terrorize the world with an army of enormous robotic dinosaurs. As the only beast strong enough to save humanity from the mechanical dinos, Kong must rely on the help of three kids who know the truth about him."[53]

- The King Kong suit from King Kong Escapes appeared on Ike! Greenman episode 38 called Greenman vs Gorilla. Due to copyright reasons, King Kong's name was changed to Gorilla.

Related films

- The premise of a giant gorilla brought to the United States for entertainment purposes, and subsequently wreaking havoc, was recycled in Mighty Joe Young (1949), through the same studio and with much of the same principal talent as the 1933 original. It was remade in 1998.

- King Kong bears some similarities with an earlier effort by special effects head Willis O'Brien, The Lost World (1925), in which dinosaurs are found living on an isolated plateau. Scenes from a failed O'Brien project, Creation, were re-used for the 1933 Kong. Creation was also about a group of people stumbling into an environment where prehistoric creatures have survived extinction.

- The Mighty Kong, an unofficial (this is why it was called Mighty Kong rather than King Kong) straight to video 1998 animated musical/remake of the 1933 film. It featured the voices of Jodi Benson as Ann Darrow and Dudley Moore as Carl Denham. This film also featured a song score by the Sherman Brothers. At the end of the film, King Kong falls from the Empire State Building after getting out of the net that the blimps were using on him. Due to this being a family film, King Kong survives the fall.

- Banglar King Kong – An unofficial Bangladeshi musical based on the King Kong story and directed by Iftekar Jahan. The film uses large amounts of stock footage from King Kong and premiered in June 2010 in the Purnima Cinema Hall in Dhaka.[54]

- Other similar giant ape films include:

- The 1961 British film Konga where a chimpanzee is turned into a giant ape after being fed growth serum by a deranged scientist, and attacks London.

- The 1969 American film The Mighty Gorga which features a circus owners's quest to capture a giant ape in an African jungle.

- The 1976 Korean 3D film A*P*E.[55] where a giant ape runs amok in Seoul South Korea.

- The 1976 Queen Kong, another British film that parodies King Kong with a gender reversal between the giant ape and the object of the ape's affection

- The 1977 Hong Kong made film The Mighty Peking Man that featured a huge ape-like bigfoot that attacked Hong Kong after it was brought to Hong Kong from its territory somewhere in India near the Himalayas.

King Kong in the name

There were other movies to have borne the "King Kong" name that have nothing to do with the character.

- A lost silent Japanese short, Japanese King Kong (和製キングコング Wasei Kingu Kongu), directed by Torajiro Saito featuring an all-Japanese cast and produced by the Shochiku company, was released in 1933. The plot revolves around a down on his luck man who plays the King Kong character on a vaudeville theater to earn money to woo a girl he likes. The film doesn't actually involve King Kong per say.

- King Kong Appears in Edo (江戸に現れたキングコング Edo ni Arawareta Kingu Kongu). A lost two part silent Japanese period piece that was produced by a company called Zensho Kinema in 1938. The film revolves around kidnapping and revenge amongst the characters. The "King Kong" in this film is a trained ape (that looks more like a yeti) who is used to kidnap one of the characters. Judging by the plot synopsis presented by periodicals at the time, the "King Kong" is regular sized and is only depicted as gigantic on the advertisements for promotional purposes.[56]

- The 1959 Hong Kong film King Kong's Adventures in the Heavenly Palace which featured a normal sized gorilla.[57]

- The Hindi films King Kong (1962) and Tarzan and King Kong (1965) which featured the professional wrestler King Kong and has nothing to do with the famous movie monster although the latter film featured a normal sized gorilla.

- The 1968 Italian film Kong Island (Eva, la Venere selvaggia, literally Eve, the Wild Woman) which was advertised in the U.S as King of Kong Island. Despite the American title, the film featured normal sized gorillas and takes place in Africa.

- The 1981 Mexican film Las Muñecas Del King Kong (The Dolls of King Kong) which featured exotic jungle girls. The "King Kong" in the film was simply a giant ape statue on top of a building.

Parodies

- In Mad Monster Party?, the giant gorilla "It" (with the vocal effects provided by Allen Swift) is a larger knock-off of King Kong and is most likely named "It" due to copyright reasons. Baron Boris von Frankenstein didn't send an invite to "It" since "It" can be a bore and had crushed the Isle of Evil's wild boars the last time "It" was invited as he explained this to his assistant Francesca. Boris has his zombies patrol the island just in case "It" shows up uninvited. When "It" does show up, it goes on a rampage and snatches up the monsters and Francesca (where "It" develops a crush on her) and climbs the Isle of Evil's tallest mountain. Boris convinces "It" to take him instead of Francesca which "It" complies to. After Francesca is off the island with Boris' nephew Felix Flanken, Boris sacrifices his life where he drops the vial containing the secret of destruction which destroys himself, "It," the Isle of Evil, and everyone else that was on it at the time.

- In Mad Mad Mad Monsters (a "prequel of sorts" to Mad Monster Party?), there was a knock-off of King Kong called Modzoola.

- The corpse of the 1976 King Kong makes an unauthorized appearance in the film Bye Bye Monkey.

- King Kong appears in the 1996 Imax film Special Effects: Anything Can Happen. In this film, the classic climax of the 1933 film is recreated with modern (at the time) digital special effects.

- King of the Lost World (a direct-to-video movie produced by The Asylum) taking elements from both King Kong and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World. The film was released on December 13, 2005, just one day before the theatrical release of Peter Jackson's version of King Kong. The Gigantopithecus is a giant ape that appeared in the 2005 movie King of the Lost World (a loose adaptation of The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle). It is estimated to be 9.8 feet high and has an interest in attacking intruders as it threw a flight attendant in the beginning of the movie. It eventually got intimidated when a plane chases it with a torch.

- King Kong appears in the Where My Dogs At? episode "Buddy and Woof Do the MTV Movie Awards." He appears on the stage background at the MTV Movie Awards hosted by Jimmy Fallon (who was the back-up host after Dave Chappelle slipped on a banana peel during his intro and had to be taken to the hospital). After Jimmy Fallon makes a comparison of King Kong and Jack Black after Jessica Simpson gave birth to Jack Black's child, King Kong ended up crushing Jimmy Fallon with his fists much to everyone's delight. When the MTV Movie Awards are over, King Kong gets out of his shackles and heads home.

Electronic games

Tiger Electronics released various King Kong games in the early 1980s. These include

- A Tabletop LCD game in 1981[58]

- A game for the Atari 2600 home video game system in 1982[59]

- A handheld game in 1982 in both a regular edition[60] and a large screen edition.[61] The regular edition was later reissued by Tandy in 1984.[62]

- An "Orlitronic" game (for the international markets) in 1983[63]

- A color "Flip-Up" game in 1984.[64]

Epoch Co. released two LCD games in 1982. One was King Kong: New York,[65] and the other was King Kong: Jungle[66]

Konami released 2 games based on the film King Kong Lives in 1986. The first game was King Kong 2: Ikari no Megaton Punch for the Famicom, and the second was King Kong 2: Yomigaeru Densetsu,[67] for the MSX computer. In 1988, Konami featured the character in the crossover game Konami Wai Wai World. All these games were only released in Japan.

Data East released a pinball game[68] in 1990.

Bam! Entertainment released a Game Boy Advance game based on Kong: The Animated Series in 2002.[69]

MGA Entertainment released an electronic handheld King Kong game (packaged with a small figurine) in 2003.[70]

Majesco Games released a Game Boy Advance game based on the straight to video animated film Kong: King of Atlantis in 2005.[71]

Peter Jackson's King Kong: The Official Game of the Movie which is based on the 2005 remake was released on all video game platforms. It was the first game released by Ubisoft on the Xbox 360. Another game called Kong: The 8th Wonder of the World was released for the Game Boy Advance.

Taiyo Elec Co released a King Kong Pachinko game in 2007.[72]

Besides starring in his own games, King Kong was the obvious influence behind other gigantic city destroying apes, such as George from the Rampage series, Woo, from King of the Monsters (who was modeled after the Toho version of the character) and Kongar, from War of the Monsters. As well as giant apes worshipped as deities like Chaos and Blizzard from Primal Rage.

Pop culture references

King Kong, as well as the series of films featuring him, have been featured many times in popular culture outside of the films themselves, in forms ranging from straight copies to parodies and joke references, and in media from comics to video games.

The Beatles' 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine includes a scene of the characters opening a door to reveal King Kong abducting a woman from her bed.

The Simpsons episode "Treehouse of Horror III" features a segment called "King Homer" which parodies the plot of the original film, with Homer as Kong and Marge in the Fay Wray role. It ends with King Homer marrying Marge and eating her father.

The British comedy TV series The Goodies made an episode called "Kitten Kong", in which a giant cat called Twinkle roams the streets of London, knocking over the British Telecom Tower.

The controversial World War II Dutch resistance fighter Christiaan Lindemans — eventually arrested on suspicion of having betrayed secrets to the Nazis — was nicknamed "King Kong" due to his being exceptionally tall.[73]

Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention recorded an instrumental about "King Kong" in 1967 and featured it on the album Uncle Meat. Zappa went on to make many other versions of the song on albums such as Make a Jazz Noise Here, You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore, Vol. 3, Ahead of Their Time, and Beat the Boots.

The Kinks recorded a song called "King Kong" as the B-side to their 1969 "Plastic Man" single.

In 1972, a 550 centimetres (18.0 ft) fiberglass statue of King Kong was erected in Birmingham, England.

The second track of The Jimmy Castor Bunch album Supersound from 1975 is titled "King Kong".[74]

Filk Music artists Ookla the Mok's "Song of Kong", which explores the reasons why King Kong and Godzilla shouldn't be roommates, appears on their 2001 album Smell No Evil.

Theme park rides

Universal Studios had two popular King Kong rides at their theme parks in Hollywood and Orlando.

The first King Kong ride was called King Kong Encounter and was a part of the Universal Studios Studio Tour (Hollywood) in Hollywood. The ride opened in 1986 and was destroyed in 2008 in a major fire. Universal opened a replacement 3D King Kong ride called King Kong: 360 3-D that opened July 1, 2010.[43][75]

A second more elaborate ride was constructed at the Orlando park in 1990. It was called Kongfrontation. The ride was closed down in 2002, and was replaced with Revenge of the Mummy in 2004.

See also

- Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.

- The Lost World (Conan Doyle novel)

- Edgar Wallace

- Gigantopithecus blacki

- Universal Monsters

- KING-TV and KONG-TV

- King Kong (Toho)

- Donkey Kong

- Mighty Joe Young (1949 film)

- Ingagi

- Godzilla

- Clover (creature)

- Titano

References

- ↑ Boland, Michaela (2009-02-09). "Global Creatures takes on "Kong"". Variety.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ Yamato, Jen (December 12, 2014). "King Kong Pic ‘Skull Island’ Moves To 2017; Zhang Yimou’s ‘Great Wall’ Epic Dated For 2016". Deadline.

- ↑ Fleming Jr., Mike (December 15, 2014). "‘Whiplash’s J.K. Simmons To Star In ‘Kong: Skull Island’". Deadline.

- ↑ Fleming Jr., Mike (January 7, 2015). "Michael Keaton In Talks To Join ‘Kong: Skull Island’ For Legendary". Deadline.

- ↑ Fleming, Jr, Mike (September 16, 2014). "Legendary’s ‘Skull Island'; Tom Hiddleston Stars, Jordan Vogt-Roberts Helms King Kong Origin Tale". Deadline. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ↑ Fleming Jr., Mike (October 30, 2014). "King Kong Tale ‘Skull Island’ Gets Rewrite From ‘Flight’ Scribe John Gatins". Deadline.

- ↑ Wigler, Josh (January 15, 2015). "Michael Keaton And J.K. Simmons Preview Their Trip To ‘Kong: Skull Island’". MTV.

- ↑ "King Kong Live on Stage at the Regent Theatre, Melbourne". Kingkongliveonstage.com. 2014-03-17. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ↑ "Joe DeVito (Creator/Illustrator of Kong: King of Skull Island)". Scifidimensions.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ Boy's Magazine Cover (jpg image).tinypic.us

- ↑ "Official site". Kongskullisland.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ Matthew Moring (January 29, 2012). "Press Release: Doc Savage and King Kong Coming in March". Press Release. Altus Press. Retrieved 2013-02-24.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "1933 RKO Press Page Scan".

- ↑ Goldner, p. 37

- ↑ Goldner, p. 159

- ↑ James Van Hise, Hot Blooded Dinosaur Movies, Pioneer Books Inc. 1993 p. 66

- ↑ Morton, p. 36

- ↑ Karen Haber, Kong Unbound. Pocket Books, 2005. p. 106

- ↑ Morton, p. 205

- ↑ Morton, p. 264

- ↑ Weta Workshop, The World of Kong: A Natural History of Skull Island. Pocket Books. 2005

- ↑ "King Kong- Building a Shrewder Ape".

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Vaz, pp. 193–194

- ↑ Vaz, p. 190

- ↑ Morton, p. 25

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Vaz, p. 220

- ↑ Goldner, p. 185

- ↑ Vaz, p. 277

- ↑ Vaz, p. 361

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Vaz, pp. 362, 455

- ↑ Vaz, p. 362

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Vaz, pp. 363, 456

- ↑ Morton, p. 150

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Vaz, p. 386

- ↑ Morton, p. 158

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Vaz, p. 387

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd. 55 USLW 2152 797 F.2d 70; 230 U.S.P.Q. 409, (2nd Cir., July 15, 1986).

- ↑ Morton, p. 166

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Vaz, p. 388

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Vaz, p. 389

- ↑ According to Mark Cotta Vaz's book on p. 389, and citation 9 on p. 458, this quote is taken from a court summary from the document Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd., 578 F. Supp. at 924.

- ↑ Second Court of Appeals, 1986, 77–8.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Mart, Hugo (2010-01-27). "| King Kong to rejoin Universal tours in 3-D". Latimes.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ Gill, Raymond (2009-09-18). "Kong Rises in Melbourne". Theage.com.au. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "King Kong live on Stage Official Website". Kingkongliveonstage.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "Robotic King Kong to star in stage musical". CBC News. 2010-09-16.

- ↑ Morton, pp. 239, 241

- ↑ "King Kong Stats Page".

- ↑ "King Kong".

- ↑ "King Kong (2nd Generation)".

- ↑ "Lost Project: Operation Robinson Crusoe: King Kong vs. Ebirah". Toho Kingdom. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ↑ Steve Ryfle. Japan's Favourite Mon-Star. ECW Press, 1998. p. 135

- ↑ "Netflix sets plans for animated series 'Kong - King of the Apes'". Entertainment Weekly. October 1, 2014. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ↑ The Ongoing Travels of King Kong. Roberthood.net (2010-06-11). Retrieved on 2012-12-21.

- ↑ Ape (1976). imdb.com

- ↑ 高槻真樹 (Maki Takatsuki). 戦前日本SF映画創世記 ゴジラは何でできているか (Senzen Nihon SF Eiga Souseiki). 河出書房新社 (Kawadeshobo Shinsha publishing). 2014. Pgs.183-188.

- ↑ "King Kong's Adventures in the Heavenly Palace".

- ↑ "Tiger King Kong". Handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "King Kong (US) Box Shot for Atari 2600". GameFAQs. 2009-06-02. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "Tiger King Kong LCD". Handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "Tiger King Kong Large Screen". Handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "Tandy King Kong LCD". Handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- ↑ "Tiger King Kong (Orlitronic)". Handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "Tiger King Kong Color". Handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "Grandstand King Kong New York". Handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "Epoch King Kong Jungle". Handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "King Kong 2 Box Shots and Screenshots for MSX". GameFAQs. 2009-06-02. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "The Internet Pinball Machine Database". Ipdb.org. 1931-11-20. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "Kong: The Animated Series (US) Box Shot for Game Boy Advance". GameFAQs. 2009-06-02. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ Game photo (jpg image). tinypic.com

- ↑ "Kong: King of Atlantis (US) Box Shot for Game Boy Advance". GameFAQs. 2009-06-02. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ CR伝説の巫女 at the Wayback Machine (archived June 3, 2010). taiyoelec.co.jp (November 2007)

- ↑ Laurens 1971, pp. 168–169,

- ↑ "AllMusic". Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "Badass New Teaser Promo for Universal's New King Kong Ride". Dreadcentral.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- Notes

- Goldner, Orville and Turner, George E. The Making of King Kong: The Story Behind a Film Classic, A.S Barnes and Co. Inc. 1975

- Morton, Ray King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon. Applause Theater and Cinema Books, 2005 ISBN 1557836698

- Vaz, Mark Cotta (2005). Living Dangerously: The Adventures of Merian C. Cooper, Creator of King Kong. Villard. ISBN 1-4000-6276-4.

External links

- The 1933 film King Kong at the Internet Movie Database

- Official King Kong (2005) movie website

- The 2005 remake King Kong at the Internet Movie Database

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||