Kilcronaghan

| Kilcronaghan | |

|---|---|

| Irish transcription(s) | |

| • Derivation: | Cill Chruithneacháin |

| • Meaning: | "Church of St. Crunathan" |

| |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| County | Londonderry |

| Barony | Loughinsholin |

| Townlands | 21 |

| Settlements | Tobermore, Kilross |

Kilcronaghan (from Irish Cill Chruithneacháin, meaning "Church of St. Crunathan"[1][2]) is a civil parish in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. Containing one major settlement, Tobermore, and lying on the descending slope of Slieve Gallion, Kilcronaghan is bordered by the civil parishes of Ballynascreen, Desertmartin, Maghera, and Termoneeny. It lies within the former historic barony of Loughinsholin and is situated in Magherafelt District Council. As an ecclesiastical parish it lies within the Diocese of Derry and Raphoe.[3]

Artefacts of human habitation in the Kilcronaghan area have been traced as far back as 1800-1000 BC.[4] The history of the parish itself can be traced as far back as the 6th century when St Crunathan founded the church from which it takes its name.[4][5] It has been the site of massacres and executions,[5][6] with the River Moyola which flows through the parish forming the border between the ancient kingdoms of Ui Tuirtri and Fir Li.

Topography

The parish of Kilcronaghan lies on the descending slope of Slieve Gallion (from Irish Sliabh gCallann, meaning "mountain of the heights"), with its highest point lying in the townland of Gortahurk, 1,246 feet (380 m) above sea level. From here it slopes downwards to low gravelly hills, which predominate in the parish. This series of hills become more broken and irregular as they approach the River Moyola.[7]

Prominent hills in Kilcronaghan parish are (townland in brackets); Brackaghlislea (in Brackaghlislea), 465 feet (142 m) high; Mormeal (in Mormeal), 438 feet (134 m) high; Bonfire Hill (in Tullyroan), 377 feet (115 m) high; Donnelly's Hill (in Gortahurk), 356 feet (109 m) high; Drumbally (in Coolsaragh), 313 feet (95 m) high; Calmore Hill (in Calmore), 268 feet (82 m) high; Killynumber Hill (in Killynumber), 238 feet (73 m) high; Todd Hill (in Gortamney), 201 feet (61 m) high; and Fortwilliam (in Tobermore), 200 feet (61 m) high.

The River Moyola flows through the parish's northern extremity along with a few small rivulets, and forms the boundary between Kilcronaghan and the parish of Ballynascreen (Ballinascreen). There were formerly 16 small lakes in the parish, residing largely in the townlands of Brackaghlislea, Tullyroan, Gortahurk, and Mormeal.[7] A small lough named as Lough Aber lies in Ballinderry townland, whilst a smaller lough lies in Killytoney.

The natural wood of the parish of Kilcronaghan consists of oak, ash, birch, alder, hazel and holly with thorns.[7] The vast majority of the woodland has been deforested though small woods lie in Mormeal and Killytoney, whilst Nutgrove Wood lies in the townlands of Gortahurk and Tullyroan. A large oak called the Royal Oak grew near Calmore Castle in Tobermore. Until it was destroyed in a heavy storm, the Royal Oak was said to have been so large that horsemen on horseback could not touch one another with their whips across it. From this vague description, it is conjectured that the Royal Oak was about 10 feet (3.0 m) in diameter or 30 feet (9.1 m) in circumference. Another oak tree that once grew near Tobermore was so tall and straight that it was known as the "Fishing Rod". Tradition is that the whole of the townlands were once covered with magnificent oak trees.[7]

Nothing but oak is found in the small bog of Coolsaragh. The flow bog of Tullyroan and Gortahurk has all been cut.[7] Ballynahone Bog lies in the townlands of Ballynahone More and Ballynahone Beg, and is the second largest lowland raised bog in Northern Ireland and has been declared a Special Area of Conservation.[8]

Drumbally Hill

Drumbally Hill, consisting of 0.12 hectares was declared on 24 September 2010 to be an "Area of Special Scientific Interest" (ASSI).[9] It provides access to an important exposure of limestone, dating from the Carboniferous period around 320 million years ago. This dating has been backed up with the discovery of fossil shell fish and crinoud fragments that date from the period. The exposure was left from a large quarry that once existed on the site.[9]

Unlike many other limestone exposures which are usually pale in colour, the exposures at Drumbally Hill are of a red-brown colour. This colouration signifies that the rock had been altered since it was originally deposited, most likely by groundwater. The limestone rock at Drumbally Hill was formed as a lime mud onn the floor of a shallow, tropical sea. Its proximity to a shoreline resulted in quartz sant grains and pebbles becoming embedded into the mud leaving a large amount than what is usual for the majority of limestone.[9]

Townlands

History

People have inhabited the Kilcronaghan area since prehistoric times, with minor artifacts found in Kilcronaghan and the neighbouring parishes of Desertmartin and Ballinascreen dating as far back as 1800-1000 BC.[4]

From the early Celtic period, c. 500 BC to the arrival of the Normans at the end of the 12th century, date the settlement sites that where erroneously recorded by the surveyors of the 1800s as forts or Dane forts,[4] with at least 20 such 'forts' known in the parish (listed below). They were mostly circular enclosed farmsteads, containing several thatched wooden huts. The parish of Kilcronaghan receives its first mention in history in the papal taxation of 1302-1306, under the name Kellcruchnathan, where it was a minor benefice valued at only 6s. 8d. Despite this low valuation it consisted of some of the richest lands in the River Moyola valley.[10]

Prior to the Plantation of Ulster, Kilcronaghan was part of the ancient Irish district of Glenconkeyne. Along with this the termon or erenagh lands of the parish consisted of the townlands of: Ballintrolla, Derrekerdan, Dirrygrinagh, and Kellynahawla. With the plantation these townlands passed into hands of the Bishop of Derry, however from the mid-17th century their names had become Granny, Mormeal, Tamnyaskey, and Tullyroan. It is impossible however to determine or match which townland corresponds to which of the older names.[10]

The Plantation of Ulster also saw the townlands of the parish divided with most going to the Drapers company. The Vintners company received lands in the north and east of the parish, with the church also receiving several. The two townlands of Tobermore and Grenan (a now obsolete townland merged with that of Tobermore) were granted as freeholds of William Rowley,[10] brother of John Rowley, the chief-agent of The Honourable The Irish Society.

The Bull of Pope Paul V

On 29 March, 1609, a Papal Bull from Pope Paul V gave Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, the "advowson of certain Rectories and Perpetual Vicarages on the dioceses of Armagh and Derry, respectively". Whilst praising Hugh O'Neill for his zealousness against what the Pope calls "heretics" (Protestants), it states the parishes to be included in this advowson, listing Kilcronaghan amongst then.[11]

Irish Confederate Wars

It is claimed that a massacre took place at Drumbally Hill within Kilcronaghan shortly after that of Island MacHugh (Island Magee) in January 1642, during the Irish Confederate Wars. Eighteen Scotch families removed from the County of Antrim, settled in the neighbourhood and committed a "cold blooded massacre upon the Irish occupants of the land".[6] In 1834, the names of those families could still be remembered, though none of said families now remain in the area.[6]

In March 1642 during the same war the then leader of the rebellion in Ulster, Phelim O'Neill, ordered that his soldiers where to come to Kilcronaghan to be reviewed. In the townland of Calmore on 21 April he spent the night in the house of Lieutenant Crosby, who submitted to him and was noted as being a "good Catholic". From Kilcronaghan O'Neill would travel to Coleraine.[12]

On 6 August, 12 Scotch soldiers went to the parishes of Kilcronaghan and Maghera, where they were followed by Irish forces who killed or drowned them in the River Bann.[12]

Executions

When the nearby village of Desertmartin held the county court of County Coleraine, all those condemned to die were executed or hung from a stone that projected out over the door of the old Kilcronaghan parish church. This stone had a gutter cut to embrace the rope and prevent it from slipping from the stone during an execution. During the rebellion of 1641, in which Phelim O'Neill was engaged, and even in subsequent periods, the old Kilcronaghan parish church was still the scene of executions. The hanging stone was in 1806 built into the new church.[5]

Local superstitions

In the Statistical Reports of Six Derry Parishes 1821, there are listed three superstitions that were held by people of the area:

Firstly it is claimed that people in the Kilcronaghan and Ballinascreen (Ballynascreen) parish areas once believed in the 'occult virtues' of the Ballinascreen Bell where those who swore upon it became cursed.[13] There are two recorded stories of people swearing on the bell and misfortune occurring to them afterward:[13]

- A Mr Higgins, from the townland of Gortahurk, was accused of stealing some articles from a neighbouring farmer. He procured the ancient bell, brought it to the scene of the accusation and swore an oath upon it. However instead he suffered immediate mental derangement, a condition he would have until his death. It also affected two of his offspring.

- A woman who made a voluntary, but unlawful oath, on the Ballinascreen Bell, suffered from mental derangement for many years.

The second superstition, which was supposedly held by on the large by the Roman Catholics of the country, was that an oath taken on the Bible was not binding as if taken on their "own Manual or Prayer Book".[13]

The third superstition was the blinking of cows. This superstition held that you mustn't "mix milk of one quarter with that of another quarter, lest their cows should be blinked, as it is believed that mixing the milk is the reason of so many cows being blinked". Not even a single drop of the last quarter of milk would be mixed with that of another, in either sweet or butter milk.[13]

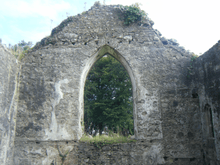

Kilcronaghan parish church

The original parish church of Kilcronaghan stands in the townland of Mormeal, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) away from the present day parish church. Local traditions claim that this church was founded by Saint Crunathan, a bishop and son to a late king of Munster, sometime in the 6th century and afterwards named after him.[4][5] Saint Cronaghan is also alleged to have been the foster-uncle of the famed Saint Columba.[4]

Records from the church show payments by the church's herenach in 1397 of 12s and in 1609 of 13s4d. A herenach was a person or family expected to maintain the church lands and support the bishop and clerics within proceeds from the land. The church was rebuilt in the 13th century, incorporating several Norman styles, and by 1622 was described as being ruinous. In 1693, it is recorded that there were only eight families in the parish "and of these not above twelve or thirteen comfortable persons". During the next century ownership would transfer from the Roman Catholic Church to the Church of Ireland, and by 1768 it was back in good repair, with the parish containing 126 Protestant families of 510 persons by 1831.[5]

In 1806, the ancient parish church was again rebuilt but on a smaller scale, incorporating several of its older 13th century features such as a fine Norman niche, capital, modern window jambs, the western gable, and the northern wall, with the rest being pulled down. Above the door into the church was carved - "Rebuilt 1806 Rev William Bryan Rector - James Stevenson Esq. and Thomas Jackson - churchwardens - Leverty builder", which reads as the church rector at the time being Rev William Bryan, the church wardens being James Stevenson Esq. and Thomas Jackson, with the building having been rebuilt. A ledge used for hanging people, which had been part of the church for centuries was also built into the church.[5]

During the overhauling of the ancient parish church, several raised tombs and ancient graves standing in the interior were disturbed, with several skulls raised out, all with silk caps upon them, none of which could be removed due to the passage of time. Along with this was discovered in the graves a number of gold rings and other jewels supposed to have been worn by nuns and buried with their remains in the body of the church. Also found in one of the graves was an ancient book that had become "quite defaced by time and damp...". By 1823, only 17 years after being rebuilt to the parishes needs, the old church no longer met the needs of the growing population of Tobermore and the parish, and was declared inadequate in the accommodation of the congregation. So on Monday 27 February 1854, it was agreed to build a new parish church on a new site.[5]

By 1855, the Rev Marcus McCausland offered a site in the townland of Gortree (now part of Moneyshanere), which was accepted and on 13 April 1858, the new church was consecrated by the Lord Bishop of Derry and Raphoe, the Right Reverend William Higgin. The Coleraine Chronicle states that the church "is built of grey stone, in the Gothic style of architecture, and reflects great credit on the architect, Mr W Mullan, and his efficient workmen." The present Kilcronaghan Parish church celebrated its 150th anniversary on 13 April 2008.[5]

See also

- List of civil parishes of County Londonderry

- List of townlands in Tobermore

- Saint Crunathan

- Tobermore

References

- ↑ Logainm Placenames Database of Ireland - Kilcronaghan entry

- ↑ Derry & Raphoe Diocese - Parish of Kilcronaghan

- ↑ Derry & Raphoe Diocese

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Ordnance Survey Memoirs for the Parishes of Desertmartin and Kilcronaghan, Ballinascreen Historical Society. Published 1986

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 150th Anniversary of Kilcronaghan Parish Church, Kilcronaghan Parish Church, 2008. ISBN 978-1-906689-05-6.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Mr. John O'Donovan's Letters from County Londonderry (1834)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Richardson, H: Ordnance Survey Memoirs of the Parishes of Desertmartin and Kilcronaghan 1836-1837, pages 32-35. Ballinascreen Historical Society, 1986

- ↑ Geography Location - Ballynahone Bog

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Northern Ireland Envrinoment Agency; Drumbally Hill - Area of Special Scientific Interest

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Toner, Gregory, Places-Names of Northern Ireland, page 112. 1996

- ↑ Flood, W. H. Grattan, Bull of Pope V, pages 39-40.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Ua Muipeadhaigh, Lopcán, An Irish Diary of the Confederate Wars, pages 207-225.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Statistical Reports of Six Derry Parishes 1821 - Ballinascreen Historical Society. Published 1983